Sorry, I am not actually taking money bets on this yet, but I do think I’m right, and I may be ready to take some cash bets from you in a few weeks.

For now, he’s just getting some serious brushback — no threats yet of an actual burning at the stake — but that’s only because those council members who already don’t like his ideas don’t yet fully realize what they are. When they become cognizant of what the city manager’s new scheme really represents — making economic decisions rationally — they’ll kill him. They will have to.

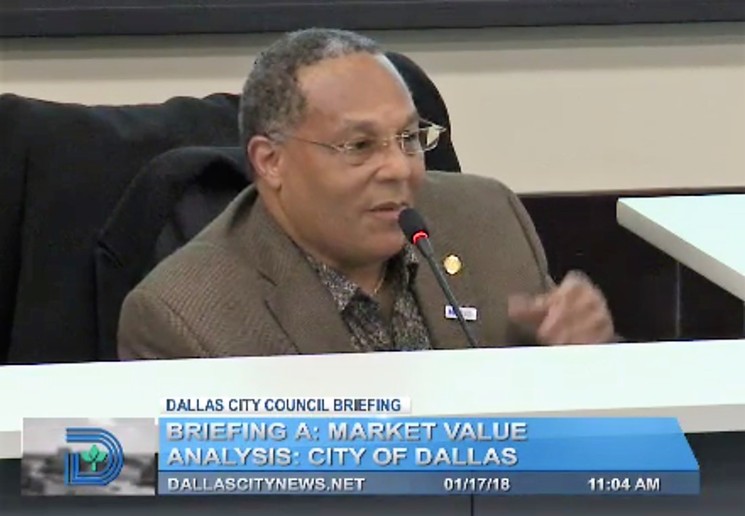

At Wednesday’s council briefing, City Manager T.C. Broadnax presented information on something called “market value analysis,” or MVA, a sophisticated, detailed analysis carried out over a six-month period by The Reinvestment Fund, a nonprofit research group in Philadelphia that has executed similar analyses of more than 30 other major American cities.

The point of the analysis is to identify exactly what’s going on socioeconomically in every neighborhood in the city. Who cares? Well, the City Hall has an annual budget north of $3 billion. The way the city spends and invests that money has a lot to do with what it’s like to live in certain neighborhoods. Also, it’s our money, so we shouldn’t want the city to spend it on things that won’t do anybody any good.

How would that happen? Here’s an example. The city has X amount of money to fix the streets and storm sewers. Some guy who plays golf and goes to the right church comes along and says he wants to build a 20-story office building in a certain area, but he wants a $10 million gift, called an incentive, from the city. Otherwise, he won’t build.

If the city gives it to him, that’s $10 million less the city has to spend on streets and storm sewers, but maybe it’s worth it to get a development built that will pay higher taxes later.

The MVA is a series of maps showing exactly where different parts of the city stand in terms of promise and need. The MVA maps might reveal that the place where the guy wants to put his 20-story building is already boiling with development activity, with investors from all over the world elbowing to get in.

In other words, we don’t need to give that guy 10 million bucks. If he goes away, too bad; there’s a line of people down the block to replace him. So the answer is no."How do you incorporate what I’m seeing in real time to the research that you have done? Because it doesn’t match up to me.” — Kevin Felder

tweet this

The MVA might reveal that the area where he wants to build is right on the edge of transition and a new 20-story office building would be just what the doctor ordered. The $10 million gift, then, might be a good investment for the city to make for the future, even if it will take money away from streets and sewers now. So the answer is yes.

Or, lastly, the MVA might show that the area where he wants to put his building is just too heavily hammered, too weak and bleak, too far gone, for now, anyway. If he puts his building there, he’s going to lose all his money, and so will the city if it gives him $10 million. So that answer is no again.

Why would any of this cause the city manager to be burned as a witch? Well, please don’t be offended, but I’m surprised you would even have to ask me that. It should be obvious.

Under our single-member City Council system, especially where real estate development is concerned, each council member is king or queen of his or her district. They alone pick winners and losers in their districts, and they pick them according to their particular tea leaves.

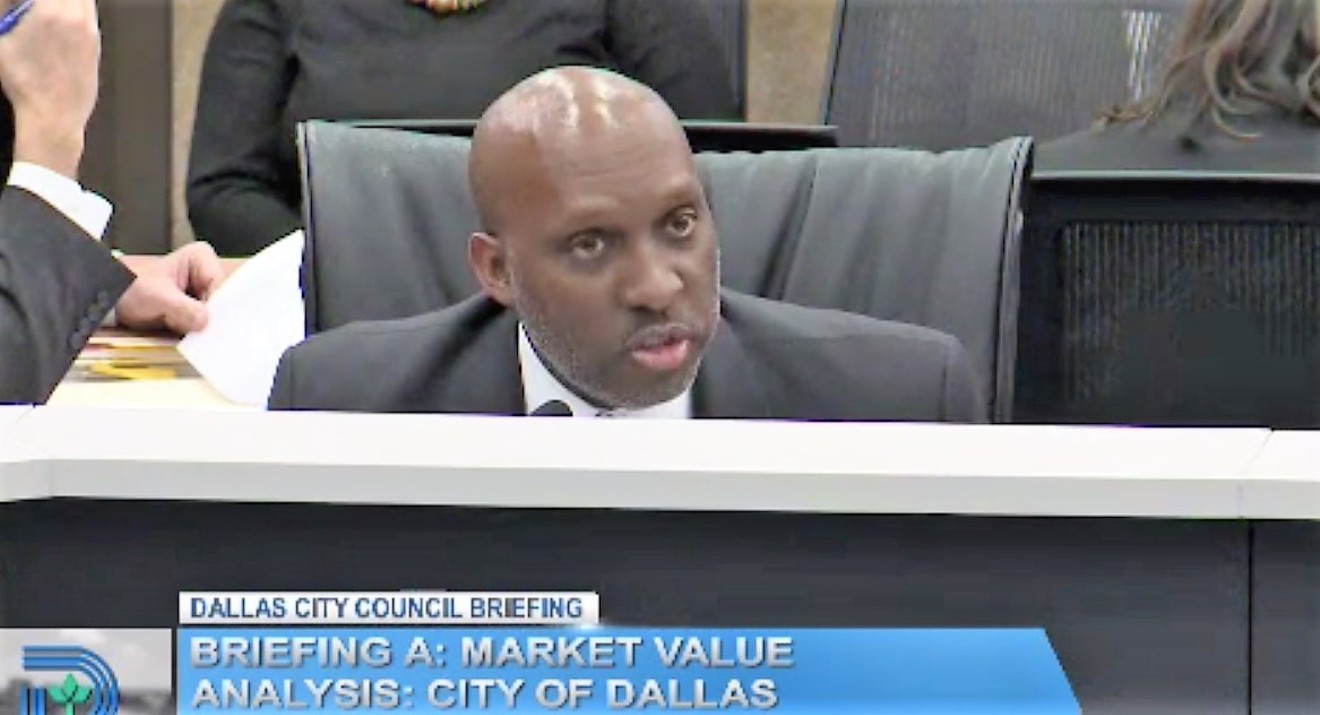

District 7 City Council Member Kevin Felder was almost apoplectic at Wednesday’s meeting, incensed that the MVA had identified a neighborhood called Buckner Terrace as a place in his district where incentives would do the most good. He was angry because that’s not where he says incentives should go.

Felder wants the city to pour money into an area called South Dallas/Fair Park near the city’s aging and neglected 277-acre exposition park a couple of miles southeast of downtown. Scientific analysis be damned.

“I see something wrong here,” Felder said. “How can you say that Buckner Terrace has more potential for development when I am seeing it in real time? How do you incorporate what I’m seeing in real time to the research that you have done? Because it doesn’t match up to me.”

By “doesn’t match up,” he means he doesn’t like it. If there is incentive money to be had, Felder wants it to go to South Dallas/Fair Park, one of the city’s most economically beleaguered terrains. And here we begin to home in on what’s really going to give the city manager a hot-foot before this is over.

Several council members observed Wednesday that the MVA maps confirm a reality of which everyone has been aware for decades but of which people have only recently begun to speak. Dallas is severely segregated, racially and economically, and it’s not by accident.

This is a city where racial segregation goes straight back to slavery and then comes forward in an unbroken line to the present. The dramatic economic and social disparity between north and south is the product of deliberate, persistent policies of segregation and deprivation.

Dallas City Council member Kevin Felder already knows who he wants to get economic development money, and science be damned.

dallascityhall.com

But the work of The Reinvestment Fund over several decades all over the country points to a different conclusion: It won’t work. Maybe it’s morally satisfying to say that the bad rich white people should pony up the money to make things better in the poorest and most blighted parts of the city, but, even if they did, which they won’t, it won’t work.

Infusions of subsidy can marginally accelerate improvement in a neighborhood, but only if the spark is there already and organically. An area to be helped must be helping itself in some degree already for outside help to do any good.

The Buckner Terrace area, just south of Interstate 30 in East Dallas, has a long proud history of neighborhood activism. I can testify as a personal witness that Buckner Terrace was one the key areas that led the way in neighborhood organizing in Dallas, back when City Hall still lumped neighborhood organizing in with communism and smallpox.

The research — not just The Reinvestment Fund’s research but a growing consensus in the field — shows that dropping big cash infusions into totally decimated areas just won’t work. The money evaporates. There is no human infrastructure there to catch it and put it to good use.

But putting money into areas that already have something going for themselves — called nodes of opportunity — is a way to push that organic strength out toward the decimated areas. The hot embers of opportunity must be carried out toward the coldest reaches of poverty by people who already know how to handle opportunity.

And right there, bang! We just hit a big brick wall. The whole idea of reinforcing organic success conflicts directly with the model of restitution.Parachuting bundles of money into a blighted district will not create a healthy regional economy where none existed before.

tweet this

The rich white bastards took the money. Tell them to load it up on a pickup truck and send it back. By the way, I give myself no pass here whatsoever. I personally have always found satisfaction in the rich-white-bastards-and-a-pickup concept, in part, perhaps, because, whatever else I might be, at least I’m not rich.

But it doesn’t work. And, in fact, the restitution model reinforces stereotypes, as if wealth can only come from rich white people and only as a grant. Building on nodes of opportunity, on the other hand, assumes that nonrich people can figure out their destinies.

Yes, we have to stop actively working to thwart economic justice. We have to root out all kinds of informal red-lining that create unfair barriers. Every little chance we get, it would be nice if we could be less racist. But, no, parachuting bundles of money into a blighted district will not create a healthy regional economy where none existed before. It’s just harder than that and requires a lot more self-sufficiency.

So I see Broadnax running back and forth between two brick walls. One is a model deeply rooted in local politics, based on direct restitution and social justice more than on what works economically or pragmatically. The other is simply single-member districts. I don’t care what kind of science it is; if it tells Kevin Felder something he doesn’t want to hear, MVA will be bad medicine to him.

The only answer will be to hold a trial, dunk Broadnax in a vat of water 10 times and declare him to be a witch. Burn him. Then give Felder his $10 million subsidy for South Dallas/Fair Park. By then, I’ll probably be on Felder’s side because, hey, I don’t want to get burned.