Don and Joan's method of parenting seemed to work. Wes and Andy were both the kind of kids that made other parents envious of Don and Joan's fortune. Andy was the valedictorian of his class and a football star in Malakoff, the East Texas town where the family ended up after Don's career as a musician wound down. Wes was a valedictorian at Malakoff High School too, but his only appearances on the football field came when he led the marching band during its half-time routines as a drum major.

They both won college scholarships, though that's where the similarities end. Andy stayed in school and went on to become a doctor, while Wes dropped out and devoted his time to playing guitar in Tripping Daisy. And at every step of the way, Don and Joan were there, never telling their sons what to do, just helping them do it. Yet looking back, there is one thing Don Berggren wishes he had told Wes to do. Or not do, actually.

"I don't remember whether I ever said, 'Wes, you can't do drugs,'" Don Berggren says. He stares at the carpet in his apartment just off Munger Avenue. "If I didn't, God help me."

Wes Berggren died of a drug overdose last month. The toxicology report, released last week by the Dallas County Medical Examiner's office, found traces of cocaine, propoxyphene, and benzodiazepine in his body. Wes' wife, Melissa, called his father at 5:15 p.m. on October 27, telling him that Wes wasn't responding to her. Though Don says he didn't quite know what to make of that statement, he ran out of the house anyway, leaving the door wide open. He raced down to Wes and Melissa's apartment, which was about a block away from his own, and began trying to administer CPR. But he knew almost as soon as he arrived that it was already too late.

"I knew pretty much that it was futile because of the temperature of Wesley's skin," he remembers, slowly letting the words come. "Then the medics came and went in there. They came back out a few minutes later and said, 'He's gone.' So then I had to call his mother. It's not something you can rehearse for. It's not something that you can say, 'How're you doing? How was your day? By the way...' And then I had to call his brother, and that was even worse. They were so close, not just best friends. He's having a hard time of it."

Don is having a better time of it, but less than a month later, he's still trying to figure out how it could have happened, how his youngest son could have been taken from him much too soon. Sitting in a recliner, facing a wall covered with pictures of his two sons, he's careful with his words, not wanting to sound as though he's blaming anyone for Wes' death. It was an accident, he says, an error in judgment that can't be taken back. The only thing that will bring Wes back from death, if only for a little while, is remembering his life.

So that's what he's doing on this unseasonably warm afternoon, telling stories about his sons the way only a father can, with pride and love and maybe a little exaggeration. Yet each one seems to end the same way, with a moment that didn't seem out of the ordinary at the time, but now holds a sort of cruel irony. Like how Don, after seeing Wes act in a production of Waiting for Lefty in college, went up to him backstage after the show was over and said to him, "That's great, Wes. I'll never have to worry about you again."

But, for the most part, Don's stories have less to do with the way Wes died than the way he lived. Perhaps the one that sums up his life best is more than two decades old.

Wes was only 7 years old at the time, but he was already a handful. It was just another lazy summer afternoon, the kind of day made for fishing and drinking and little else. Don and his buddy Royce McAfee were doing a little of both that day, sitting around the stock pond on McAfee's stretch of land in East Texas, talking about the Beatles, catfish, whatever comes up when two old friends get together. The conversation wasn't that important then, and it matters even less now. They were just doing their best to waste the day on a spot of land they'd been visiting for years, ever since McAfee set up a gig in Dallas for Berggren's band, Sweetgrass.

Wes was also with them, busying himself with repeated attempts to catch one of the turtles that occasionally poked their heads up out of the tank looking for fresh air. But every time he'd try to sneak into the water, the turtles would scatter, not falling for a 7-year-old's ruse. After a while, McAfee took Wes aside and patiently explained to him that he was wasting his time trying to nab one of the turtles. It couldn't be done.

And that appeared to be that. Berggren and McAfee turned their attention back to their fishing poles and sweaty bottles of beer, and Wes, apparently giving up on the turtles, went to find the kind of adventure that most young boys crave until they discover girls. Wes and Andy had spent many days exploring the creek beds and woods in the area, with their dog Hussy -- the mutt Wes had rescued on a junior-high playground -- and Don doing their best to keep up. Of course, Wes had not actually given up -- he was just devising a new plan. A few minutes later, he dove into the pond again, disappearing into the murky water for a few seconds before emerging again victorious, clutching a turtle in his hand.

"That's quintessential Wes," Berggren says, thinking about the story. "We learned early on that you couldn't really tell Wes what to do."

Each story Don tells is bracketed by long pauses, as he tries to figure out what to say next. He looks a little like Wes would have if he had reached his father's age, though Don's beard and salt-and-pepper ponytail obscures the connection at first. Sometimes, it seems as if he's deciding whether to say anything else at all. He often stops before he starts, as soon as he feels as though he's heading down a road he's not ready to take. Other times, he slows down so he can make sure every detail is right, fact-checking his stories as he tells them. The pictures that practically wallpaper his apartment touch off memories, which lead to others. Some are happy, others are not, and Don does his best to get through them all, falling silent when it becomes too much for him.

It's a disjointed conversation, though it's hard to expect any discussion like this one to continue in a straight line. Berggren is just now beginning to work through it all, convincing himself that when he wakes up in the morning, Wes still won't be here. A week ago, after the medical examiner confirmed what he already knew, he was angry. He wrote a letter to the Dallas Observer that ended chillingly: "If you're a parent, pause a moment and think about the words you'll search for to write your kid's obituary." Now, he's just trying to move on. And he has, at least a little bit, finally returning to his job as a medical social worker. But it hasn't been easy.

"I don't think I'm going to say anything original," he starts, trying to explain how the last few weeks have been. "To find out and experience first-hand how many friends Wes had, that was a great experience. With something like this, you'll take comfort anywhere you can get it. Some of it's kind of thin, in terms of content. But some of it's just so overwhelmingly relevant that you take it home with you, and you think about it for a long time. That's happened to me a lot with some of his friends. The memorial service is a really good example of that."

Many of the people who spoke at Wes' October 30 memorial service were friends he'd made while growing up in Malakoff. Wes and Andy presided over a large but tight-knit group of friends there, kids that spent as much time at the Berggrens' house as they did at their own. His mother -- now Joan Bondioli -- and Don had divorced when Wes was in junior high, but they remained close friends. Today, Don says that he "considers her the greatest mother ever." Don coached Wes' soccer team, and Joan provided a place for all the kids in the area to hang out. Wes was the ringleader, the kid who did well in school, but didn't take himself too seriously. "God, that kid knew how to have fun," Don remembers, laughing.

The fun continued through high school, where Wes formed his first band with some of his buddies. Prosecution -- that was the name Andy came up with for his brother's group -- wasn't much of a band; performing a couple of Bon Jovi covers at a high-school talent show was about the extent of its achievements. And Wes was really the only one who could play his instrument. Of course, that didn't surprise his father. Wes had always been something of a natural when it came to music.

"He inherited most of his musical talent from his grandmother, whom he never knew, my mother," Berggren says. "She was quite the genius. When he was three years old, I used to be able to go over to the piano, and -- with my back turned -- I could strike a note, walk over and say, 'Go play that note, Wes.' And he couldn't see which one I had played, but he could play it. Didn't matter where in the register. He just had that, you know?"

Over the years, Wes and his father always had that connection, the common ground of music to fall back on. The last time Don spoke with his son, the day before he died, that's what they talked about. "He liked to let me know that the music was going well, because he knew I thought about that a lot," he says.

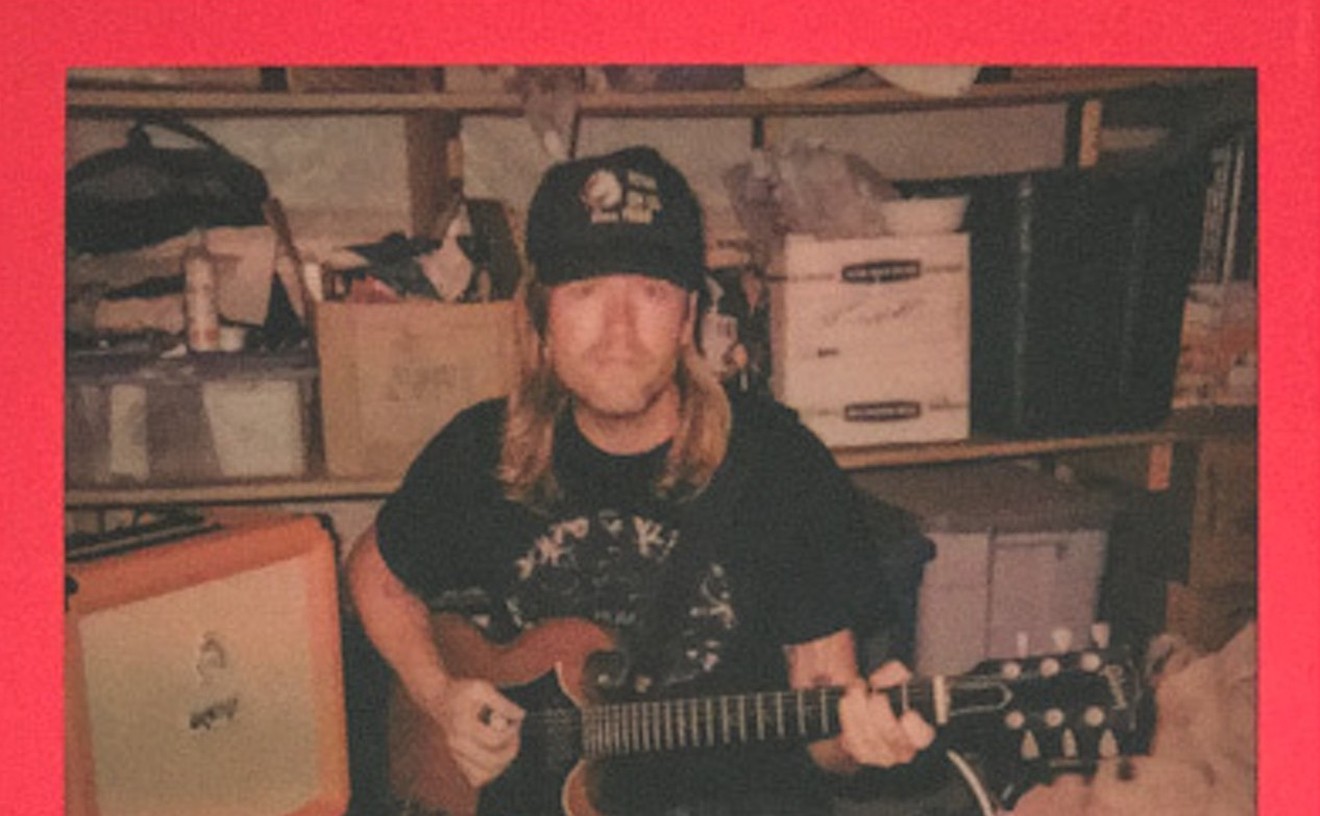

Even now, the connection remains: The day before our interview, Don added some piano tracks to a Tripping Daisy song, playing the parts that Wes had intended to but never had a chance to record. And when Wes formed Tripping Daisy in 1991 with Tim DeLaughter and Mark Pirro, he called his father to come see them play in the shack behind DeLaughter's Ross Avenue home. He wanted his opinion, both as a father and a musician.

"And I told him, 'First of all, it doesn't really matter what I think. But for what it's worth, I think you've really got something,'" Don says. "The most amazing thing they had was the rapport and the willingness and ability to work together, the total absence of ego."

Don grew close to the other members of the band in the eight years they were together, especially Pirro and DeLaughter. Tripping Daisy was a way for him to still be involved in music, and it made his son happy, so Berggren was a big fan. And even though the band had been dropped by its record label, Island Records, earlier this year, Berggren was still upbeat about the future, and so was Wes. To say that he didn't expect any of this is an understatement. Maybe he knew more about his son's habits than he's letting on, but that doesn't matter.

"I had been worried in the past from time to time, but that's just what dads do," he says. "I knew that he was on a career path that he wanted to be on and things were looking good, even though the record industry kind of did a meltdown. But that's just corporate stuff. The immediate option of using the Internet was extremely viable. In fact, it would probably even increase the parameters of creativity. So I was feeling pretty good about it. But he did the wrong thing, he did it one time too many, and that's it." Berggren stops and stares for a moment at the wall of pictures -- the photos of Wes on his freshman football team, his wedding, and the one that dominates the display, 3-year-old Wes and Don mugging for the camera. Then he continues.

"He fucked up," he says. "He just fucked up. He made a mistake that caused him not to be able to wake up. But I think that the thing that his mother and I always agreed on and practiced was that you don't put your kids into a cage. You don't put them in a playpen. You don't put them on a leash. What you do is stay within two or three feet of them and let them do whatever they want. We just weren't around this time."

Send Street Beat anything you've seen and/or heard to [email protected].