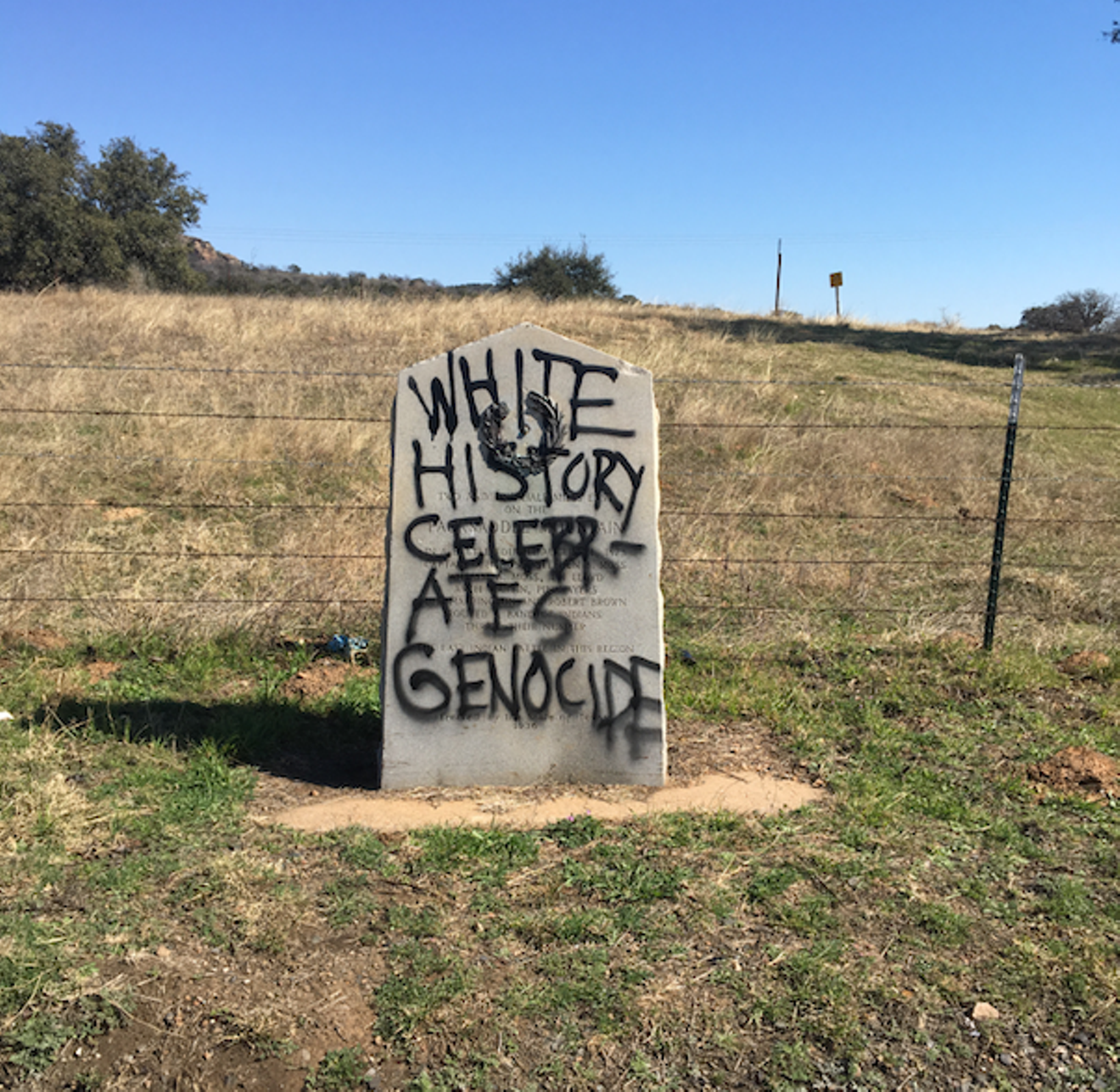

In late February, the Texas State Historical Commission (THC) received reports of attacks on three markers in Llano County, west of Killeen. One 81-year-old sign commemorating “the last Indian battle in this region” is now soaked with a black spray paint scrawl saying “White history celebrates genocide.” Two other smaller markers show signs of damage, one pocked with bullet holes and another emblazoned with “DECOLONIZE!!!” in white paint.

These signs have become targets in the ongoing war over history and culture, with some seeing biased views of hostile Native Americans on public display and others seeing an attempt at revising history to appease political correctness. Vandals have used them as a canvas for racism or, in Llano’s case, political radicalism.

But damage is unavoidable, even without vandals. Drivers hit them, pranksters steal them and junkies target the metal to sell for scrap. Rain leaches color from brass and string trimmers leave residue. The wear and tear of a public sign requires steady upkeep, but there is no dedicated money in the state budget to do so.

There are two kinds of historic markers in Texas, thin metal “subject matter markers” and the older, granite “centennial markers” that the state put up 81 years ago to celebrate the state’s birthday, March 2, 1836.

The state can handle routine fixes to the metal signs, says Chris Florance, director of public information for THC. “Staff can typically maintain the subject matter markers, but if someone cuts them off or steals them, then there’s a problem,” he says. “People think they are worth a lot of money but they are just aluminum.”

The damage to the signs could exceed $10,000. The annual budget of the county’s historical commission is $1,000.

tweet this

For example, Florance says a THC staffer will try to use putty to repair a shotgunned metal marker in Llano county later this month.

But the ultimate responsibility to repair or replace falls on local coffers. The host county needs to pay for repairs of more serious damage.

“For subject matter markers, the county is the first gatekeeper on those applications,” Florance says. “The county actually pays for markers and their maintenance. … If one is gone, sometimes it’s replaced, sometimes not.”

Llano is not exactly prosperous. According to the county, the proposed 2017 operating budget is $14.79 million. The median income for a household in the county in 2000 was $34,830 and more than 10 percent of the county is at or below the poverty line, according to census data.

County officials are estimating the damage to the two signs could exceed $10,000. Llano County Judge Mary Cunningham says that the county’s historical commission gets $1,000 each year and depends on local fundraising. “They have limited funds,” Cunningham says. “In our budget, we don’t have a lot of room to pay for stuff like that. This will definitely have an impact.”

Damaged subject matter markers can be repaired in place or even sent to the foundry in San Antonio that produces new ones. But a granite and brass centennial marker, like one of the defaced markers in Llano, is another story.

On the 100th anniversary of Texas’ independence from Mexico, the state earmarked more than $3 million dollars for “the placing of suitable markers, memorials or buildings at places where historic events occurred.” That included markers at buildings and museums, and standalone granite markers in places where Texas history was made.

These are more difficult and expensive to repair than the thin metal markers. One THC memo about centennial markers includes a litany of routine maintenance: lichen growth, water stains from sprinklers, unstable soil that cause them to lean.

And then there is the human factor, like attempts to pry off the metal parts or chips in the stone caused by car collisions. Under the heading “Shotgun Damage,” the memo advises conservators to “glue a mixture of granite dust and epoxy into the holes but must drill half-inch holes at each location to attach the filler.”

The memo also notes that “the longer the paint or marker remains on the surface, the more difficult it will be to remove.”

The THC staff doesn’t have the tools or expertise to fix centennial markers and host counties are not eager to put money toward expensive repairs. “That’s when we look for donors,” Florance says. “The donor money goes to restoration specialists. That’s likely what we’ll have to do with this one in Llano.”

The Friends of the Texas Historical Commission are the donors he’s talking about. “Despite its name, the Friends is not a membership organization but rather serves as a supporting foundation for the Texas Historical Commission,” the organization’s website says. It started in 1996 but in 2007 changed its status to a nonprofit group, “in response to requests from the Friends’ foundation donors.”

But the Friends of the Texas Historical Commission doesn’t have money for historic sign repair, either. The last dedicated campaign for historic signs took place more than five years ago, and for a humble goal. “We got a lot of small donations. The campaign goal was $25,000 and we got close to that,” says Anjali Zutshi, executive director of Friends of the THC. “We didn’t get any significant contributions from corporations or foundations.”

Between the Observer calling the organization and their return for comment, the incident in Llano has appeared on their homepage with instructions of how to join.

In Llano, they are grappling with the unexpected expense. “The plan is to try and repair the granite one,” says Judge Cunningham, who adds that they may try turning the slab around and redoing the inscription to save money. “It has historic significance as well. It’s not like you can just go out and get a new one. ... I’m all for freedom of expression, but not destroying property. It’s infuriating.”