We now have two recent independent reports on GSMP, one assembled by the administration of the Dallas school system with help from a citizen/expert advisory panel, the other put together by a citizen/expert task force called by the mayor with some of the same people on it.

Both reports draw on the same general body of research. Both come to strikingly parallel conclusions about what needs to be done to repair GSMP in our city. But then they go in diametrically opposite directions on how to get it done. That very important part is all about the money."There's a role that the philanthropic community and the business community has to play.” — Mayor Eric Johnson

tweet this

Neither report says just spend money. Both suggest specific effective investments to reduce GSMP, and then they present persuasive data to support the promise of return on those investments.

The difference is that the school district report puts its money where its mouth is. Superintendent Michael Hinojosa is arguing that there are hard cash projects — brick-and-mortar — that the district can do in order to improve instruction and also save money on a disciplinary system that too often functions as prep school for prison.

Hinojosa wants to use an algorithm to measure the availability or scarcity of important community resources near schools. His plan would then use a dedicated bond fund to replenish resources where their absence is so severe it suppresses a child’s ability to learn.

And that all has to be proved. In order to devote capital funds to social outcomes (GSMP), the Hinojosa plan would use court-defensible measures to show that GSMP is bad enough near some schools to stop kids from learning. It’s a fairly straightforward premise: Why bother trying to teach a kid to read if the kid is sitting there hungry all day worrying about getting shot?

Get healthy food into the kid’s diet, not just lunch at school but food on the table at home for the whole family. Provide enough security to actually make the kid feel safe. Then do the reading.

But here is a huge irony in comparing Hinojosa’s report with the one compiled by the mayor’s task force. The people who put together the mayor’s report actually dug deeper into the whole question of return on investment. They divided the city into 136 small, rectangular “cells” and then did the math on return on investment in each cell.

The mayor’s report presents data to show how many crimes will be eliminated for every $10,000 spent in each cell, with money directed to a specific set of programs aimed at GSMP. Then the report ranks the top 20 cells where investment will produce the greatest “profit” in terms of reducing messed-up-edness and all the mayhem and violence that are associated with it.

I’m no judge of the programs. I confess I don’t get some of them. But you know what? That’s a bridge on down the road. The agreement now between the school district report and the mayor’s report is that we have created our own messed-up-edness. We have done it over a long, deplorable course of history by withholding investment in some areas based on racism. Now we need to put the money back in. Otherwise, we live with the GSMP.

So in both reports it’s about money. Where the two reports are strikingly different, however, is in the all-important area of paying for it.

The Hinojosa report proposes a $40 million dedicated bond fund. I am told that talks are underway to create an additional matching fund that would attract money from other local governments, raising the total amount available to $100 million or more.

The mayor is a different story. Even though his own report does an excellent job showing where investment would be most effective in reducing GSMP, he offers no hard proposal for funding his own report:

“These recommendations come with price tags,” he said, “and these are things that we're going to discuss at the council level — with the government — but, before that, there's a role that the philanthropic community and the business community has to play.”

Really? The roles of the philanthropic and business communities come before government’s role? How does he figure that? Did the philanthropic community create and enforce mortgage redlining in the 1930s? Did the business community segregate the schools?

I don’t think Neiman Marcus was in on that one. Most of the fingerprints I see on this whole bloody pipe wrench belong to government, so wouldn’t it be nice for the mayor to take the lead instead of the back seat on reparations?

The real proof of the pudding here anyway is not in specific intentional discriminatory acts but in the overall disparate impact of seemingly mundane policy decisions. Let’s go back to the school district’s ideas about using bond money.

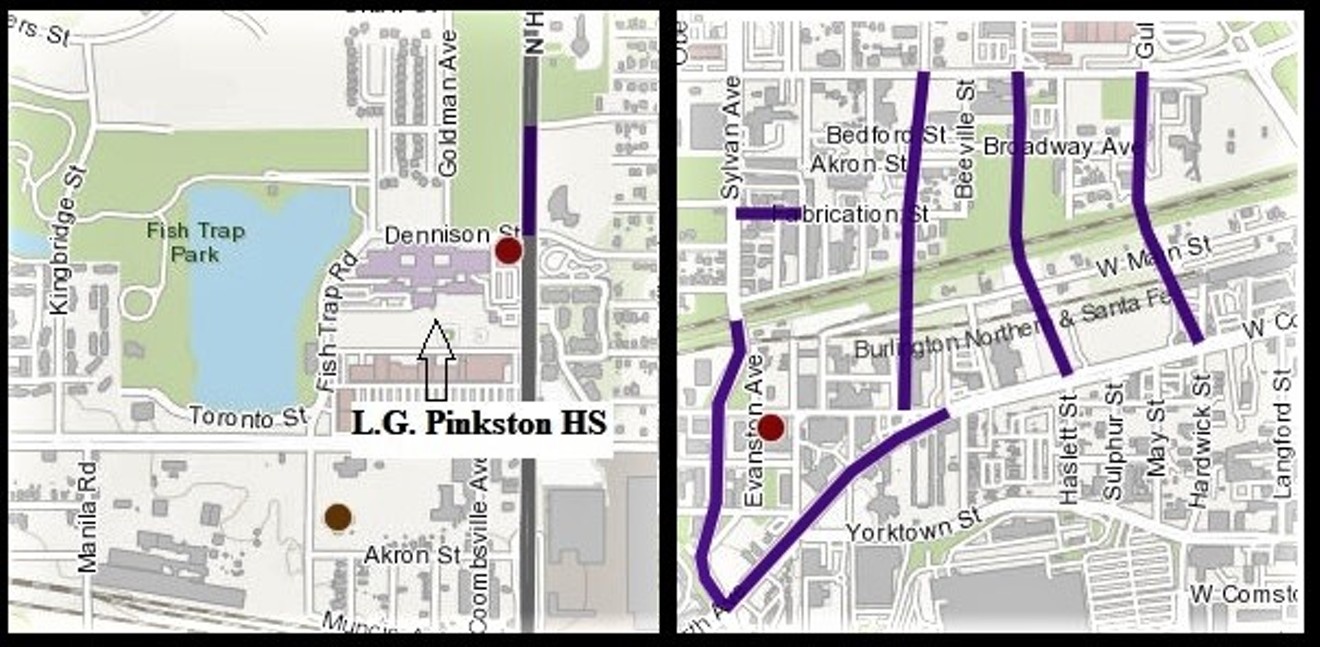

On the left, city bond projects in Uptown. On the right, the area around Roosevelt High School in southern Dallas.

Jim Schutze, from dallascityhall.com

An argument could be made that using bond money to achieve a social outcome is illegal because bond money should go only to capital expenditures — brick-and-mortar. I’m sure someone will make that argument, and the school district, if enacts its new program, will have to beat it in court.

But what if local government has been using bond money all along to achieve social outcomes, but they were racist punitive outcomes? A veritable mountain of research is in play now arguing that today’s poorest, most messed-up, most murderous neighborhoods were mapped out, planned and enforced by City Hall, the state and the feds in the first place.Barely two miles down the road from Pinkston, the city bond project desert blooms.

tweet this

How can that have been legally defensible and it’s now legally indefensible to mitigate the damage with bond money? Not to mention the moral thing, but don’t we also have a legitimate communitarian self-interest in mitigating the messed-up-edness in our midst? If we’re going to spend billions of local tax dollars on infrastructure anyway, what’s wrong with tilting at least some small portion of it toward resolving GSMP?

One of the great unproved assumptions of the ruling culture in our own city has always been that development itself — building stuff — is always good for the city because it builds the tax base. Nobody ever does the math on how much the new development costs the tax base in new services.

It’s just a leap of faith that public subsidy of real estate development builds a better city. Well how about a leap of faith for subsidizing the amelioration of general social messed-up-edness?

Might that not even be the more responsible way to spend our money in the strictly fiduciary sense? Just thinking out loud here, but last week, Laurence D. Fink, founder and chief executive of BlackRock, described by The New York Times as the world’s largest asset manager with $7 trillion in investments, announced his firm will start valuing companies in part on the basis of their preparedness for global warming. So the money meets the real world.

Why shouldn’t we think the same way about how local government spends our money? When bond rating agencies set about measuring the soundness and health of local government, shouldn’t they at least take a look at how the government is addressing profound social dysfunction? How long is any city going to do well if it doesn’t do anything about its … you know … murder problem (sorry).

It’s at least worth an interview question: “Well, then, it looks as if you folks have really done a great job with those balky traffic lights. So, tell us, how are you coming on your murders?”

The school district report proposes three pilot areas near high schools where the district could try out its new “equity in bond planning” idea. Two are in southern Dallas — Lincoln High School & Humanities Communications (worst school name ever) a half-mile southwest of Fair Park, and Franklin D. Roosevelt High School six miles due south of downtown. The third is L.G. Pinkston High School in West Dallas, two miles west of the Margaret Hunt Hill (Calatrava) Bridge.

On the left, colored lines and dots depict city projects in a neighborhood in Far North Dallas. On the right, an area of roughly the same size around Lincoln High School in South Dallas is lightly touched by bond projects.

Jim Schutze, from dallascityhall.com

Of the three comparisons I made, one was with an area in the far northern reaches of the city and another with an area in Uptown. Those were interesting — striking, in fact. Compared to what’s going on in Far North Dallas and Uptown, the area around Lincoln is only lightly touched by bond projects and the area around Roosevelt High School is a city bond project desert.

But I thought Pinkston was even more interesting. Of the three, Pinkston is in the most extreme desert. I did not compare Pinkston with areas far away from it, however. Instead I moved my cursor over barely two miles to the area at the western foot of the new Calatrava Bridge.

Oh, my! Barely two miles down the road from Pinkston, the city bond project desert blooms. The land south of Singleton a quarter-mile from the bridge is crisscrossed by bond projects. The area near the bridge also is chock-a-block with new commercial and apartment construction, some of it carried out by the famous family member of a sitting City Council member from North Dallas.

The Calatrava Bridge itself arguably was conceived and built to spur economic activity, since the only thing over there before it was built was Ray’s Hardware and Sporting Goods. (Ray’s now offers bumper stickers proclaiming, “The Bridge to Ray’s Hardware.”) It’s that third comparison, Pinkston with the foot of the new bridge, that shows what the city can do or not do if and when it feels like it.

The mayor’s own report cries out for him to offer at least that much leadership. But, you know, in addition to being our mayor, Johnson’s got a new full-time job in the public finance section of a big law firm, awarded to him right after he got elected. He’s a busy, lucky man.