“I guess that was my dad getting shot,” he said.

The PBS children's show Mister Rogers' Neighborhood began with a routine, Fred Rogers singing “Won’t You Be My Neighbor?” as he changed his jacket for a sweater and slipped on a comfy pair of shoes. At 79, Vincent Apilado also was a man of routine: daily morning coffee at McDonald’s and a copy of The Wall Street Journal, meals served at the same time. The retired business professor from the University of Texas at Arlington often slept on the sofa in the living room because Steven, who was mentally ill and sometimes violent, couldn’t be left alone when he was unable to sleep. A family man and devout Catholic, Vincent was a skilled violinist who turned down a scholarship to The Juilliard School to pursue degrees in business and finance.

Steven’s father always took care of him, even as Vincent aged and got dementia, severe arthritis and Parkinson's disease. “He had become a shell of a man who could not dress himself or shave himself, feed himself or bathe himself,” says his wife, Elsa Apilado.

Steven helped Elsa care for his father when his own illness didn't prevent him. He would bathe his father, shave and dress him, and cut his food. He would take him for his morning coffee at McDonald's. They were best friends and referred to each other as partners.

Then there was the other Steven, outlined in a trail of police reports spanning nearly a decade. Steven terrorized his family with uncontrolled violent outbursts. Years of therapy, medication and hospitalization failed to contain his anger and aggression. The family moved from Arlington to El Paso, where Steven's older brother lived, in January 2013 for a change of scenery that Vincent and Elsa hoped would help calm Steven, but his condition worsened.

“We were so desperate that we had a priest perform an exorcism,” Elsa says. “Everything that we tried failed. Maybe the devil took over.”

El Paso prosecutors painted a different picture at Steven’s December 2016 murder trial.

“So past is prologue,” prosecutor Ivan Martinez told jurors. “Are y’all familiar with Shakespeare and The Tempest? Right? What brought us to this point? Is it a mystery? No. Every single thing that we have ever done in our lives has brought us to this moment. And that's what brought Steven Apilado to his moment to decide to kill his father.”

Maybe it was fate that led 37-year-old Steven Apilado to an 80-year sentence in a Texas prison, where researchers estimate that somewhere between 15 percent and 25 percent of inmates have severe mental illnesses. In a family with doting, aging parents sheltering a son with intractable mental illness in a state with scarce resources to deal with diseases that medical science struggles to define and treat, what else might have been done to avoid Vincent Apilado’s death at the hands of his son, best friend and partner?

Early warning

When he was a child, Steven had a problem with hopping. He would hop all the time like a puppet from Mister Rogers' Neighborhood starting at about 18 months old until he was 6 years old. He told a doctor he needed to hop in order to “imagine things.”At 8 years old, he refused to go to school because he imagined he would get AIDS and frostbite, according to his medical records. He was also obsessed with sex. His mother took him to see a psychiatrist.

“I mentioned to him the constant talking about sex,” she wrote in a medical history timeline for her son’s Social Security disability application. “I felt he had been sexually abused and later found out he was [by a family friend]. But again the doctor did not take me seriously. He said that I must make him go to school or he would be hospitalized.”

Steven was an altar boy like his older brother. They attended Mass at Saint Vincent de Paul in Arlington where Elsa, a special education teacher, also taught Confraternity of Christian Doctrine classes.

Elsa says when 8-year-old Steven would get up in the morning, he would grab a knife and run out the door saying he was going to kill himself.

tweet this

Elsa says when 8-year-old Steven would get up in the morning, he would grab a knife and run out the door saying he was going to kill himself. She would calm him down enough to get him in the car, but a counselor and principal would meet her and her husband at the school door.

“It took four people to carry him in kicking and screaming,” she says. “I can remember overhearing a mother say, 'What kind of parents would allow this to happen to a child?'”

Steven began taking psychiatric medication when he was 8. After three weeks, his symptoms eased, but by seventh grade, he began having problems sleeping and claimed to see demons whenever he was alone in his room at night. He began reading extensively, delved into religion and said he was planning “to save the Jews.” He was also more irritable, angry and violent.

“A totally new Steven emerged,” Elsa says.

The high price of treatment

Steven was 15 when he became a patient at Children's Medical Center in Dallas. He was paranoid, withdrawn, aggressive and agitated. It was the ’90s, and an enormous change in the mental health system was underway. New legislation and policies were intended to promote access to mental health services, and insurance coverage for mental illness expanded, according to a 2005 study titled “Prevalence and Treatment of Mental Disorders, 1990 to 2003,” published in the New England Journal of Medicine.The study found that the number of annual visits to mental health specialists had increased 50 percent, the number of people receiving treatment for depression tripled and the number of people with serious mental illnesses receiving treatment by specialists increased 20 percent by the end of the ’90s.

Steven had been treated at Millwood Hospital in Arlington and diagnosed with bipolar disorder. He was given Tegretol for seizures and pain and lithium to help control manic episodes, but he said the drug combination made him more agitated.

At Children's Medical Center, Steven began taking clozapine. The drug, introduced commercially in the U.S. in 1990, is considered one of the best for treatment-resistant schizophrenia. It helped to control his anxiety, agitation and paranoia. Nevertheless, a year later, Steven returned to the medical center. He wasn't sleeping and was dealing with “pressured speech, hyper-religiosity, impaired judgment and increased paranoia,” according to medical records. He received the same diagnosis of bipolar disorder, but a seizure disorder, “possibly due to the clozapine,” was added.

When Steven was released, Elsa decided to home-school him and take him on walks to Lake Arlington to help calm his mind, but his illness worsened. He began taking more medication, some of which put him in a zombielike state, and experiencing side effects such as restless legs, weight gain and insomnia.

Elsa says she and her husband tried to get Steven into a long-term treatment facility whenever a manic episode hit, but their insurance would cover only 10 days. The fiance of the couple's daughter Maya eventually loaned the family $30,000 to send Steven to a private long-term facility in Florida, but Maya says he was sent home a few days later because “they said they couldn't help him.”

Admission into one of Texas’ 10 state mental hospitals requires a referral by a mental health authority from the hospital's service area, but they are often full, with nearly 400 people on waiting lists, according to a May 2016 Texas Tribune report. “The number of beds the state pays for in private facilities has not kept up with the state's rapid population growth,” the Tribune reported.

John Dornheim, special projects manager for the National Alliance on Mental Illness in Dallas, says some boarding houses in Dallas will work with aging parents of adult children with severe mental illnesses who receive Social Security or disability checks. Some are still unregulated, but "a majority of the decent ones" are accredited by the city.

"It is a huge issue in Texas," he says. "It happens so often. Parents get too feeble to handle the adult son who is 42 and healthy.""It is a huge issue in Texas. It happens so often. Parents get too feeble to handle the adult son." – John Dornheim, NAMI

tweet this

According to Adult Protective Services, a Texas court can commit a person for up to 90 days “if the person is found to be mentally ill to the degree that there is a substantial risk of serious harm to himself or herself or to others.” But involuntarily committing a patient requires a trial and legal representation for the patient.

As the years passed, the Apilados became part of an aging population known as the “hidden figures” in the mental health community. Allan Kaufman, a professor emeritus at the University of Alabama, published a scholarly article in 2010 about the lack of resources for aging parents of adult children with serious mental illnesses. He says lack of government funding for mental health is a problem.

“It is difficult for law enforcement because they are not equipped to treat them,” he says.

Although most persons with mental illness are not dangerous, a small percentage — which Kaufman says is still a lot of people — become so.

“You got thousands of situations just like [the Apilados'] all across the country,” he says. “If you're in the mental health arena, you will find [their] story repeated over and over again.”

The violence grows ...

The first record of Steven’s domestic abuse appeared not in police reports but in a July 14, 2009, letter Maya sent to Roger Robinson, a Fort Worth psychiatrist who specializes in Asperger’s syndrome. Steven, then in his late 20s, had received several new diagnoses, including obsessive-compulsive disorder, attention deficit hyperactivity disorder and Asperger's syndrome, a milder form of autism.Maya wrote that her brother’s violent behavior had escalated.

“Many times he made our family and others feel extremely uncomfortable and in danger,” she wrote. “He is very verbally and physically abusive with my parents, our family and others who are close with him. My parents, probably because they are scared, do not give him any consequences for his actions.”

Maya described Steven's attack on their father, who was 72 at the time, saying Steven struck him in the head 15 times and spat on him in April 2009. Adult Protective Services was called several times over the years, “but every time they tried to get in contact with my dad, he could not talk because Stevie was around,” she wrote.

Maya looked up to her older brother “because he would always make you laugh and was very upbeat even though he had these internal demons.” She visited one of Steven's psychiatrists to treat her own anxiety, obsessive thoughts and insomnia.The family attended group therapy meetings at Millwood. At one meeting, Maya says, her mother discussed a dream in which she killed everybody and felt a sense of relief. Elsa was hospitalized out of fear that she would hurt someone.

Inspired by Steven, Maya first studied psychology at UT-Arlington. She wanted “to find something that could fix him.” Instead, she became an elementary school teacher.

Steven attended college with Maya, planning to become a teacher, but left the program because he couldn't handle student teaching. He graduated with his bachelor's degree in interdisciplinary studies in 2006 but dealt with many obsessive tendencies that kept him from working, including clapping endlessly and saying inappropriate phrases such as, “Maya has a stinky butt; that's why she is called a slut,” or, of their family dog, “Nadia has a stinky ass; that's why she smokes a pound of grass.” Maya says Steven also thought he had AIDS and that needles were everywhere. He needed endless reassurances, she says.

In 2008, Steven tried to arrange a marriage with a Ukrainian mail-order bride; she came to America, and he courted her for a year before she left him. After that episode, he became obsessed with guns. He tried to persuade one of his psychiatrists to write a letter stating that despite his mental illness and hospitalizations, he was mentally stable enough to own gun. The doctor didn’t, but his parents did.“The situation that Stevie lived in with my parents was a recipe for disaster.” – Maya Apilado

tweet this

“My parents chose to give him guns even when they knew he was irresponsible and didn't sleep for days,” Maya says. “They said he wanted them so he could protect himself because he was so paranoid.”

Steven pointed a gun at Maya's head and threatened to kill her in 2008, but her parents persuaded her not to press charges. Her father told her that her brother wouldn’t be able to get a job if he were convicted, and her mother said that she had made a suicide pact with Steven and they would “kill each other before it would ever go to trial.”

“I truly feel that Stevie is endangering the lives of others,” Maya wrote. “I feel at any moment he could snap and this time really kill somebody. He always has at least one gun on him. He has threatened the lives of many people. I strongly believe if he is not put somewhere away from my parents and does not receive the proper medication and therapy, he will hurt someone. This someone will probably end up being my mom or dad.”

Maya says Robinson told her that Steven needed clear boundaries, a schedule and a calm environment, none of which were provided. She says her parents dealt with martial problems over the years and separated a few times. “The situation that Stevie lived in with my parents was a recipe for disaster,” she wrote.

... and grows

Maya's letter did little to change the situation at her parents' home in Arlington. In December 2012, Steven kicked Elsa, put a handgun in her mouth and stabbed her with a pen, according to a police report. “The suspect also during the assault struck the victim on the side of the head possibly with a ceiling fan blade,” reported police.A neighbor told police the abuse started because Elsa would not let Steven lie down beside her on the bed. Enraged, he broke the bed, a television in the bedroom and the ceiling fan. Maya says he didn't like being told no.

Arlington police tried to do welfare checks, but Elsa wouldn’t come to the door and Vincent would not allow officers inside the home. Elsa says they never cooperated with police officers because a family friend who worked as a social worker warned her never to let them into the home.

“According to [the neighbor], both of the parents will defend Steven and do whatever Steven asks them to do,” police reported. “She states that they have, at Steven’s request, purchased him firearms. She states that she knows he has at least four or five firearms.”“According to [the neighbor], both of the parents will defend Steven and do whatever Steven asks them to do.” – Arlington police

tweet this

Dornheim, who works for NAMI Dallas, says parents of mentally ill children often won't call the police because "there is no leeway for mental illness" in Texas law. "If you say you've been hit, the son will be prosecuted for domestic violence like anyone else."

Dornheim also points out that Adult Protective Services doesn't "have any teeth" if families don't cooperate. He says APS in Dallas is trying to improve communication with law enforcement and Dallas Fire and Rescue because the latter is now handling welfare checks. "Unfortunately, APS' caseload is huge, so if they don't get hold of them, they have to move on to the next case," he says.

The Apilados moved to El Paso soon after the Arlington attack, but it didn't help.

“He beat us pretty badly last night, and they have him jail,” Maya wrote in a June 2014 fax to Robinson. “He hit mom with the butt of a gun and against shutters and hit and kicked her. Dad has stitches. So much blood everywhere. He just hates El Paso so much. He lost control. He would have killed us. Hit my head so hard against the wall. Tried to strangle me. Kicked me, slapped me. Dad was bleeding so bad we thought he was going to die. Mom ran out and yelled for help. Said he was punishing her.”

But again, Elsa and Vincent helped their son.

“My parents bailed him out, and I was completely against it,” Maya says. “A lot of people wouldn’t understand. I have very hard time rationalizing it myself.”

Steven later described such behavior patterns.

“I was acting like a baby, got angry, and I used force,” Steven testified at his murder trial. “My father used a lot of force. But I did learn one thing. Force, people hear it. But I’m not that person doing it all the time anymore. My parents forgave me for it.”

A couple of months after the June attack, they bought him the antique Mosin Nagant bolt-action rifle he would use to kill his father.

“I should have not allowed that rifle,” Elsa says. “You get so tired, and there is no one helping you. No one. Steven was the golden boy and the kindest person you ever knew.”

Fatal night

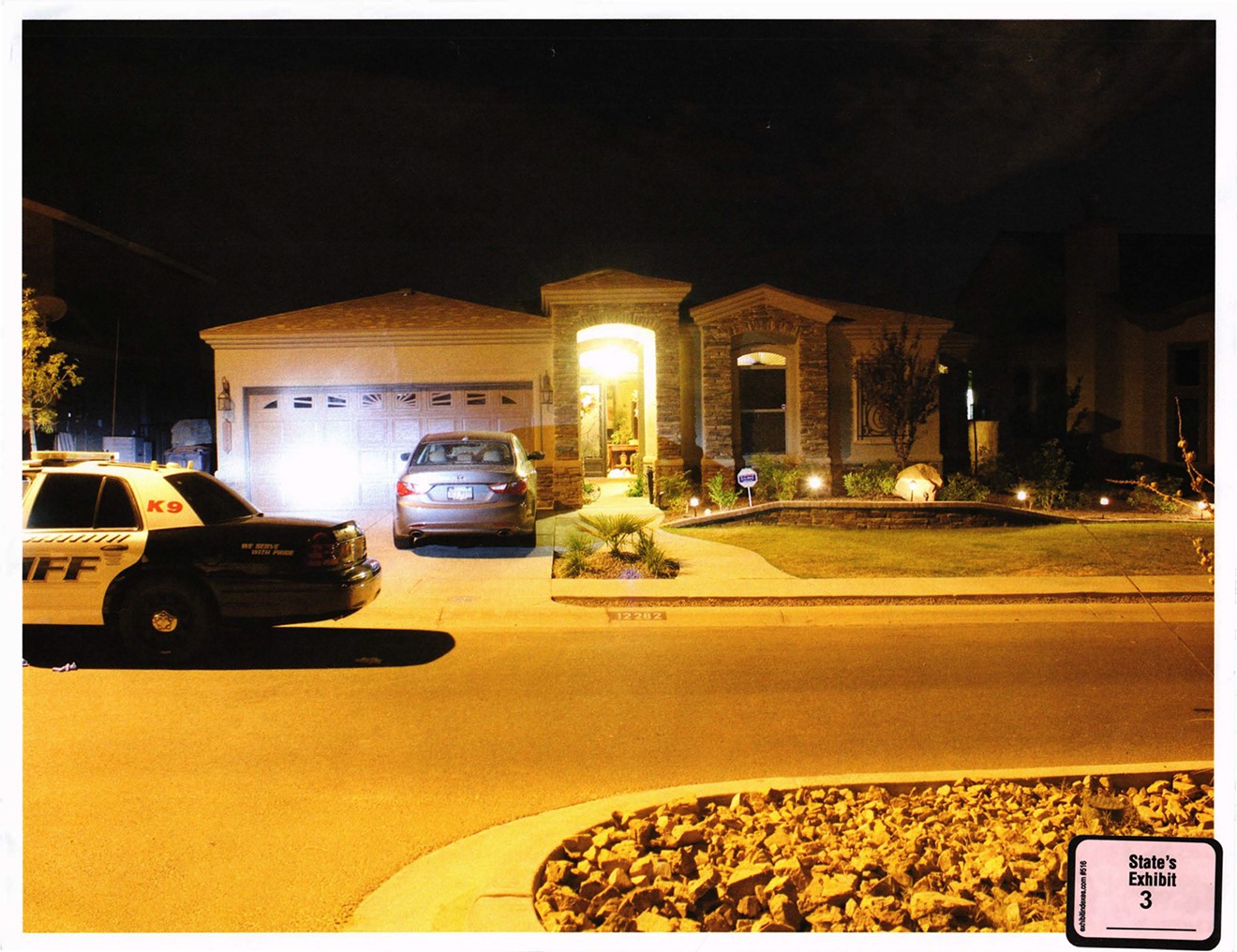

Hours before Vincent Apilado’s 2015 death, El Paso County deputies found the rifle in the kitchen pantry with three bullets in the internal magazine and one chambered, which they unloaded while they checked the house. Elsa says about 15 of them showed up and entered the home after Maya called 911 to report Steven, who hadn't slept in three days because he'd been talking “bat-shit crazy” after he wrecked the car with his father next to him earlier that morning.“And he was like, ‘I’m getting AK-47s, I have arsenic,’ and he was like ‘I’m part of the ISIS group. Mom’s crying because I murdered a bunch of people,’” Maya told a 911 operator.

No one was home when the deputies arrived. The Apilados were down the road, frightened and waiting for officers to leave, as they swept the house and secured it.

Before they left, a deputy wrote in his report: “The rifle was reloaded and placed back inside the pantry where it was located. The rifle did not have a round chambered when returned to the pantry.”

It’s unclear why his sergeant told him to return it to the pantry. Steven was still on probation for the June 2014 assault. Prosecutors said Steven was “ordered not to have any weapons in the home.”

“The [deputy] had the murder weapon eight hours before the shooting,” Maya says. “Can you imagine if he [Steven] would have gone out and shot a kid and the public were to find out he was on probation, and they knew it and left the murder weapon there?”

Several hours after the deputy returned the rifle to the pantry, Elsa says, she was pointing it at her 37-year-old son, who had rushed into her bedroom after shooting his father and begun talking rapidly. She says she'd woken earlier to see Steven dressed in black with the rifle on his shoulder. She asked him what he was doing with it, and he replied, “Don't worry. It's not loaded.”“I should have not allowed that rifle. You get so tired, and there is no one helping you. No one. Steven was the golden boy and the kindest person you ever knew.” – Elsa Apilado

tweet this

The gunshot erupted shortly before midnight.

“Mom, I don’t know what happened,” Elsa recalls him saying.

“What do you mean you don’t know what happened?” she asked.

“The gun just went off,” Steven replied. “Dad is on the ground.”

The bullet tore through his father’s head. Steven tried said he'd been sleepwalking after he watched the movie Hellraiser. But prosecutors said he didn’t fall asleep and dream of Mister Rogers as he sleepwalked. Instead, they asserted, he grabbed the rifle’s cardboard box and played with the rifle’s accessories. Crime scene investigators found bullets scattered on the floor throughout the house.

“That's smack dab right in his head,” Martinez told the jury. “That took deliberation. That took thought. It's not like he just grabbed the rifle and 'pow, pow.'”

Steven was also wearing his glasses, something prosecutors noted he wouldn’t do if he were sleeping.

For a brief a moment, Elsa told the court, she thought about killing her son. She says she knew he would not be able to live with what he had done. His father was his best friend, “his partner.” Then she thought about taking her own life.

“Why did you think about taking your life?” the prosecutor asked.

“Because it would have been so much easier for the rest of my children if we were gone and not have to be going through all this,” she said.

A whispered cry for help

The last time Maya saw her father alive, his dementia had worsened and he had begun wetting himself. She put him in adult diapers, cut up his food and pleaded with him “to be honest with the doctors and police about how Stevie was.”But it didn't do any good. An El Paso County deputy testified at Steven's murder trial that Vincent cried out during a welfare check not long before his murder.

“He was whispering to me," the deputy said. "He didn’t want his wife to hear that he was concerned for his life. He had told me that he didn't want Steven in the house anymore and that he believed he was going to be the death of him.”

Standing in the dining room of her mother's house in Denton in early November, Maya says she doesn't think Steven meant to kill her father. She spoke with him a couple of hours before the murder, and she says he sounded fearful that deputies would be returning. She says he told her that he thought they were after him because he was involved with the Russian mafia.

Nearly a year has passed since Steven was convicted, but his presence can still be felt in the old family photographs spread across the table next to the urn holding his father’s ashes. Many of them capture happier times. In one, he’s receiving an award for racquetball. In another, he’s a football player, dodging defenders.

At the trial, Steven was depicted as evil.

“Sometimes people are just bad,” Martinez told the jury. “It's not because they have Asperger's. It's not because they're tired. It's not because they had a bad dream. They're just bad.

"An entire family can try and make them not bad and try and fix things for when he's bad. Just no getting around it. People do evil things. Thankfully it's just very few people, but that's just the way it happens. They do evil things. We'll never know why. That's just the way it is.”"An entire family can try and make them not bad and try and fix things for when he's bad. Just no getting around it. People do evil things." – prosecutor Ivan Martinez

tweet this

Maya says that although Steven was an entitled, violent manipulator who could be “a plain ass sometimes,” she feels law enforcement should have been able to do something to protect her father, especially on that day when the loaded rifle was found in the pantry.

“I let it be known to police that Stevie was mentally ill, delusional, had firearms while on probation, would go days without sleep,” she says. “I called mental hospitals to try to tell them that my parents were most likely lying and that he was dangerous. I tried many times to get him arrested or put in a mental hospital.

"Our system is flawed. Why were my parents allowed to own guns while Stevie lives in their house and is on probation? I know it isn’t illegal, but given the history, it just seems like the dumbest concept.”

Maya went with her mother to Austin in February to share her brother's story at the National Alliance on Mental Illness convention. She recently joined her family in a malpractice lawsuit that her mother filed against Robinson, Steven's former psychiatrist,.

While the photos in Elsa's home show her son in happier times, the results of his actions are apparent, too.

“Muerto en vida,” Elsa says. “It means, ‘I’m dead in life.’”

She looks away, tears falling from her eyes. “I wish the police would have killed both of us. Only to spare Stevie from 80 years imprisonment and my family from the pain.”