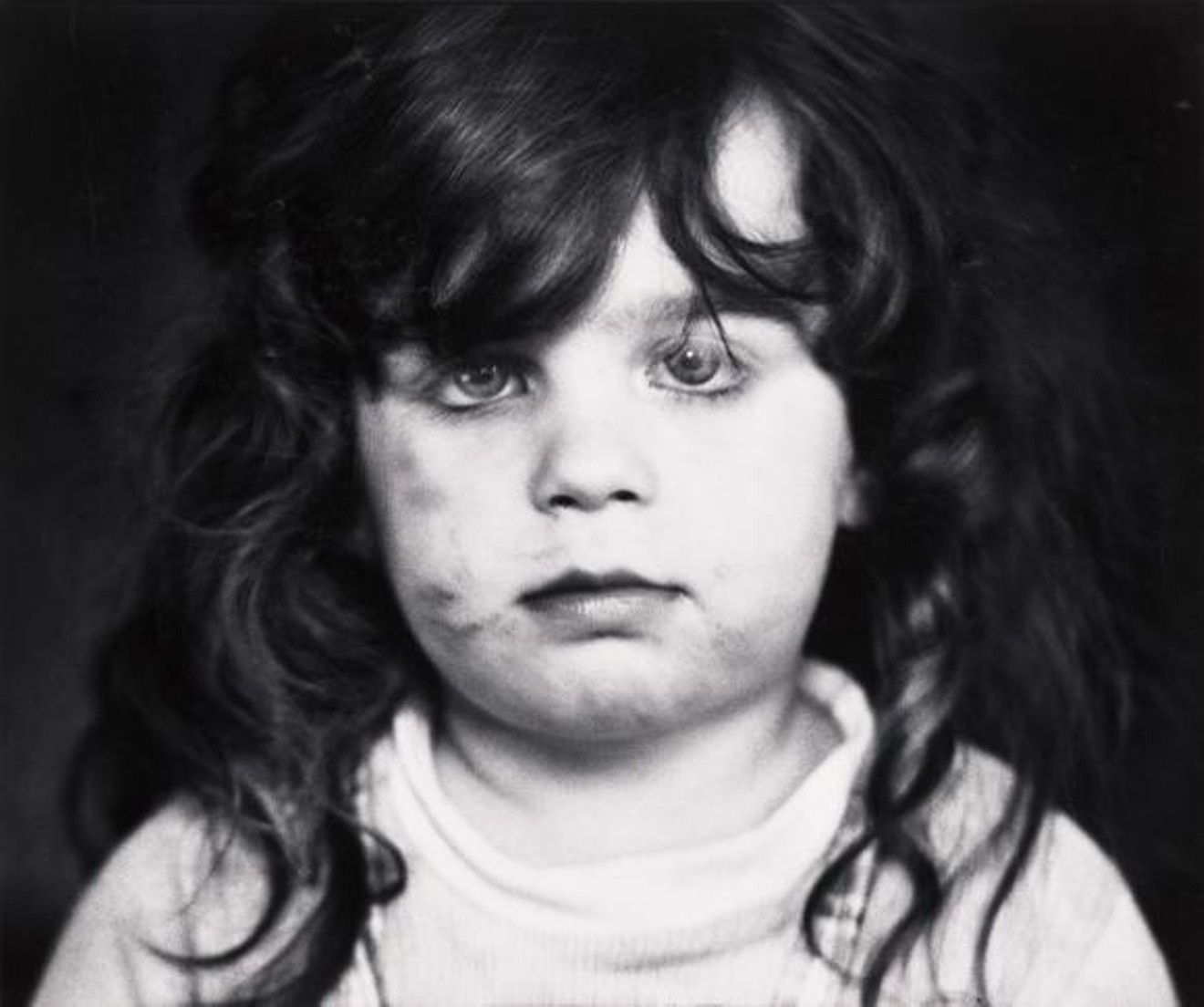

Like a Beatles tune asking where all the lonely people come from, a black-and-white photography exhibit at the Amon Carter Museum of American Art revisits the question.

Multitude, Solitude: The Photographs of Dave Heath, which runs through Sept. 16, features a collection of 150 works by the artist, mainly images from the 1950s and '60s.

Andrew Walker, the museum’s executive director, explains how the emotional upheaval of Heath’s childhood shaped his career. Left by his parents by age 4, Heath lived with his grandparents for a short time before moving into state care.

“You can only imagine what that brought to a young mind,” Walker says.

John Rohrbach, the museum’s senior photography curator, says that although Heath bounced among foster homes and an orphanage, he forged a connection to society through Life magazine as a teenager after reading a photo essay about a boy who grew in an orphanage.

“In that story, Heath sees himself and starts to pick up the camera and goes on the streets of Philadelphia to make pictures,” he says.

From Philadelphia to Chicago to New York and other cities, Heath captured somber images of people in crowds, on buses and in alleyways.

“He did it in a way that built a connection between himself and those he was photographing and us,” Rohrbach says. What separated Heath from other photographers was that his heart and soul spilled into his work.

Rohrbach says the exhibit, in some ways, is difficult because Heath shot scenes during the 1960s that were not exactly the “Kodak moment,” but were about “intimacy and holding that image in your hand and looking at it up close.

“These images take time and ask us to slow down,” he says. “You’ll realize the beauty that arises from the darker areas.”

In one image, a girl stands alone on an outdoor stage surrounded by a crowd of people whose faces seem obscure until looking more closely. In the bottom right corner of the photo, a couple kiss.

In another photo, an older couple walk along a street with rather grim expressions while holding hands.

Keith Davis, senior photography curator at the Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art in Kansas City, Missouri,

notes how Heath homed in on specific figures and focused on relationships and connections. Although the result may not be ultra-flattering, he says the photographs are sympathetic.

“He’s not making anybody look foolish,” he says. “He’s not making anybody look unintelligent. There’s a deep, deep respect on his part for his fellow citizens.”

Heath also took pictures of fellow soldiers while serving in the military as a machine gunner.

“They are tired,” says Rohrbach. “They’re thinking about home. He’s a master of picking out those types of emotions.”

For some, art is a choice, but for Heath, it was a necessity, Davis says.

“Photography and artmaking was his way of finding out who he was and how he fit in the world,” Davis says. “These are not little issues. They are not trivial concerns, and artmaking always fulfilled that function for him.

“This is sincere work,” he says. “Sincerity has truly not been in intellectual fashion for some time. Perhaps we need more of it today.”“Photography and artmaking was his way of finding out who he was and how he fit in the world. These are not little issues. They are not trivial concerns, and artmaking always fulfilled that function for him.” – Keith Davis

tweet this

The free exhibit incorporates an audio-visual component, "Beyond the Gates of Eden," as well as Heath’s book Dialogue with Solitude.

Pointing to a picture on a wall of a man playing a harmonica, Davis says the image represents what Heath, who died in 2016 on his 85th birthday, was about as an artist.

“He’s sort of a down-and-outer,” Davis says of the man in the photo. “Life has been unfair and tough for him, perhaps. But he’s an artist. He’s making art and bringing joy into the world and making music.”

The Amon Carter Museum of American Art is at 3501 Camp Bowie Blvd. in Fort Worth.