This wasn’t easy. It was sort of a mess, in fact. It’s a shame the vote today won’t be unanimous. But when you get a peek at how it finally happened, you will understand why we had better take what we can get.

In the second week of August, Dallas City Council member Philip Kingston introduced a resolution calling for an immediate moral condemnation of the Confederate monuments on city property and their eventual removal. Four other council members, including one African-American member, Casey Thomas, signed his resolution.

Dallas Mayor Mike Rawlings countered with a proposal that did not include a moral statement condemning the monuments. Rawlings’ proposal would have created a commission to consider the question of removal. It prescribed a list of hoops his commission would have to jump through first before making a recommendation on removal.

After Rawlings introduced his resolution, Thomas withdrew his signature from the Kingston resolution, and he and the other three black members of the council linked themselves to Rawlings' agenda calling for no immediate moral condemnation.

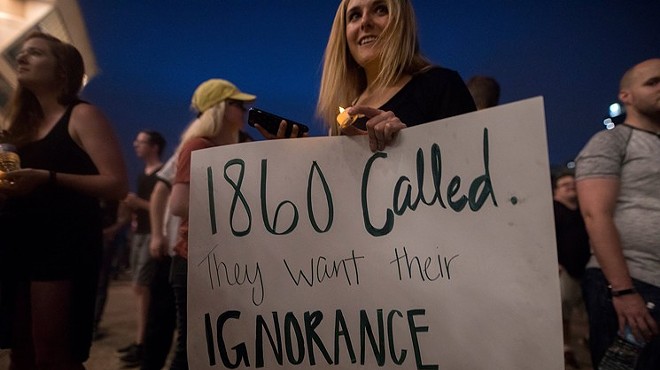

After that, 2,500 people gathered at City Hall Plaza in a mostly peaceful demonstration endorsing Kingston’s position calling for an immediate decision by the council to condemn the monuments as white supremacist propaganda. An alliance of community activists, clergy and artists came to City Hall to urge council action.

A protest at City Hall on Aug. 19 had a lot to do with a turn-around by city officials on the Confederate memorials issue.

Brian Maschino

For those few of us who keep inside baseball scores on this sort of thing, what happened here was that the mayor blinked. The mayor, hard pressed by public opinion, and the black council members, hounded by their constituents, caved to Kingston’s position. But it was important to them that it appear as if the decision to condemn came from the black council members and that Kingston not get credit.

Kingston says he doesn’t want credit. In fact, now that the moment is before us and the vote about to be taken, most of the combatants have climbed up out of their political foxholes and laid down their arms. If anything, they all seem to be a bit in awe of the moment. And you know what? That’s how it’s supposed to work. But it took us a while.

“If we are suffering from delusions, they were probably brought about by a fairly dishonest rendering of the conflict in our schools and in civic life generally." – John Fullinwider

tweet this

A wave of revulsion swept the nation after Dylann Roof tried to set off a race war by murdering nine people at Emanuel African Methodist Episcopal Church in Charleston on June 17, 2015. Communities and private entities declared their disgust by moving quickly to pull down Confederate memorials in Tampa, Florida; Lexington, Kentucky; Durham, North Carolina; Charlottesville, Virginia; Madison, Wisconsin; the city of New York; Yale University and elsewhere. We took longer.

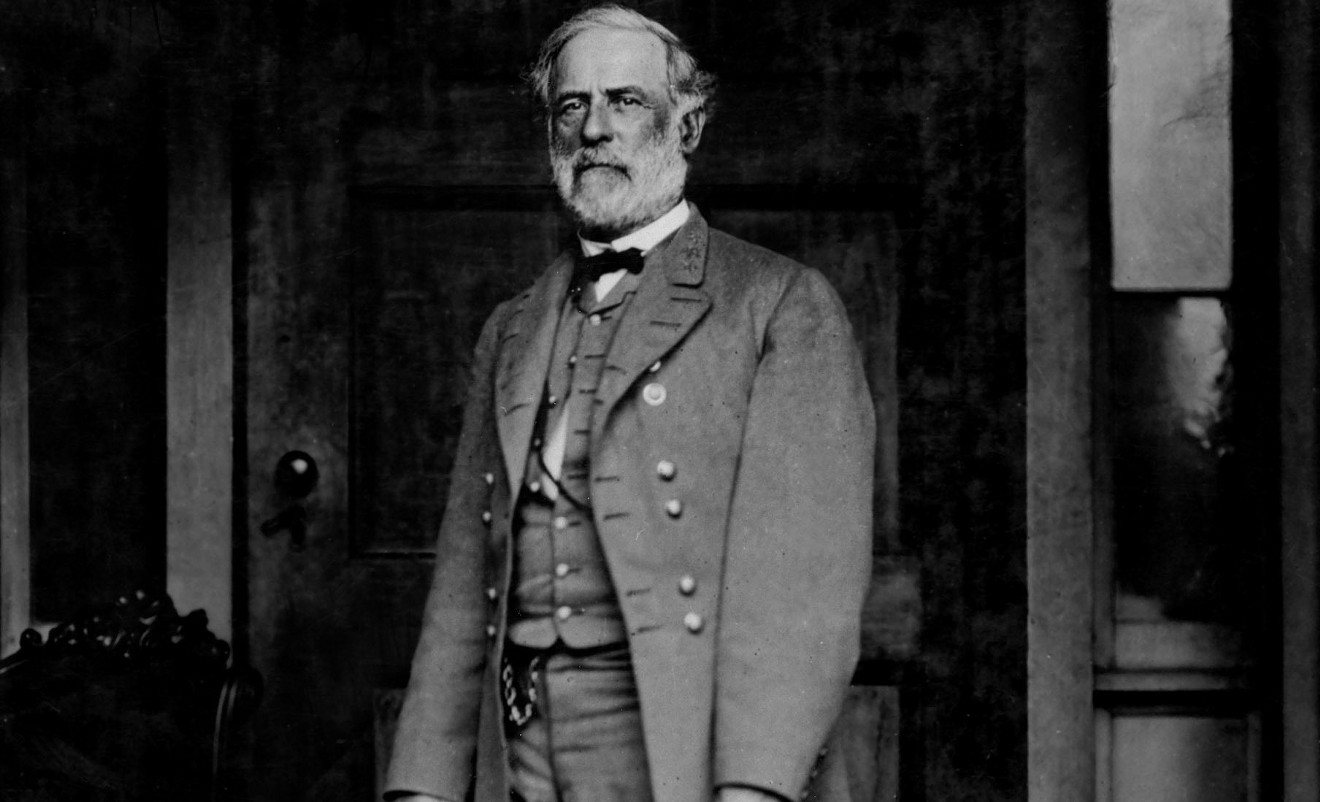

I did, too. I first wrote that some memorials like the equestrian statue of Robert E. Lee in Lee Park on Turtle Creek should be allowed to stand as markers and reminders of a dark history. I was writing from my own experience, specifically from my memory of more or less stumbling on the Lee statue after moving here in the late 1970s from Detroit.

For me, the Lee statue was like a bloody head on a pike, warning me to remember where I was. Eventually, as the current debate evolved, I realized that was exactly what the Lee statue was and why it needed to come down.

Over the Labor Day holiday, I had several conversations with people who were responsible for dragging Dallas to this moment, however kicking and screaming, and I was impressed by their humility. Community activist John Fullinwider, for example, has been involved in protests for years to demand removal of the Lee statue. But before he would talk to me about it, he wanted me to know he understands at a true gut level the feelings of the people on the other side of the debate.

“First,” he said, “I want to disclaim any moral superiority to people who are not on the front lines about this. Most whites have been totally misled in this part of the country about what the Civil War was about and what kind of a man Robert E. Lee may or may not have been, the whole thing.

“If we are suffering from delusions, they were probably brought about by a fairly dishonest rendering of the conflict in our schools and in civic life generally. It’s not saying nanna-nanna because we’re holier than you because we want the statues down. I’m not feeling that.

“For me, I went to [Dallas'] Thomas Jefferson High School. I graduated in 1970, and the athletic mascot of the school was a rebel soldier, a Confederate soldier. The school song was 'Dixie,' and the school football battle flag was the stars and bars.

Community activist John Fullinwider, part of a coalition that urged city leaders to move faster on the removal of symbols of white supremacy, has high praise for both City Council member Philip Kingston and council member Dwaine Caraway.

Mark Graham

The Rev. Michael W. Waters, pastor of Joy Tabernacle AME Church, a fifth-generation AME clergyman, told me he understood why some Dallas leaders were afraid to get out in front on the Confederate memorials question.

“One of the concerns, which is a real concern, always was whether there would be a violent response to these monuments coming down,” he said. He thought Rawlings in particular was trying to “walk the middle of the lanes so as not to incite any person.”

Waters believes the threat of racist violence was and is still very real in Dallas. “Dallas has a very nasty racial history.” But failing to do the right thing in the right moment is a surrender, he says, especially because the evil is ongoing.

“One of the concerns, which is a real concern, always was whether there would be a violent response to these monuments coming down.” – the Rev. Michael W. Waters

tweet this

“I don’t even think of that as a past-tense reality,” he said. “When I look at the disparate experiences of my community, South Dallas and south of I-30, all those things are the legacy of racial politics that’s really still coming into play today.”

He doesn’t believe that stalling and going through a process of conversation, as the mayor wanted to do, would have addressed the core problem. “I’m not sure what additional level of talking would bring around the people who really vigorously disagree," he said. "I don’t imagine that there is going to be any type of town hall forum where these people will see the light.”

Waters and Fullinwider were members of a coalition of activists, clergy, historians and artists who went to Kingston last May. Kingston says, “The credibility of the group is what got my attention.

“I got asked back in May or June by some LGBT activists over in Oak Lawn about doing it because they didn’t want the statues, either. I said, ‘Let’s get it together.' It was right about the time of New Orleans Mayor Mitch Landrieu’s speech. I kind of had it on the brain. But before they got back to me, I was approached by this coalition of folks.”

In addition to community leaders like Fullinwider and Waters, Kingston says, “All your major historians around town had signed on. The third leg of the stool that they brought was that they had Lauren Woods, the artist behind Drinking Fountain #1," the “white only” segregated drinking fountain, now an art project in the Dallas County Records Building.

“They brought her specifically to make the point that people who are going to be in favor of keeping the statues are going to make the argument that they should just be recontextualized with some sort of different art. She wanted me to know that that was not possible in her opinion, that that was not going to be an acceptable solution for this group.”

Fullinwider has high praise for the roles of both Kingston and Caraway in the bringing the question to today’s City Council vote. He points out that while Kingston’s proposal kicked it off, Caraway’s leadership brought the matter to what everyone hopes and believes will be today’s outcome — an overwhelming majority vote in favor of condemnation and removal.

The Robert E. Lee equestrian statue at Lee Park on Turtle Creek will be coming down soon, if the City Council votes as expected today.

Patrick Williams

“My mother is 89 years old, born in 1929, still living right here in Dallas,” he said. “Her father was born in 1901. That means he was 35 years old when President Roosevelt dedicated that statue" of Robert E. Lee on horseback in Lee Park.

“His father was born in the 1800s. So a very significant part of me says, ‘Hey, Pops and Paw-Paw, this is for you.’ It’s for the things that they had to endure during that era. Even though they are not here, it does give relief that I am able now and in a position to speak on their behalf when they were not allowed to voice their opinion.”