Someone who lives near the school saw them parked on the street and squealed. At least one of the students in the car smoked marijuana; Doe Jr. says he didn't. He also denied leaving campus but later admitted it.

Weed or no weed, he broke school rules. Doe Jr. — that's not his real name, of course, but is used in court filings to protect his identity because he's a minor — was then given a not-real choice. He could either withdraw from school or be expelled.

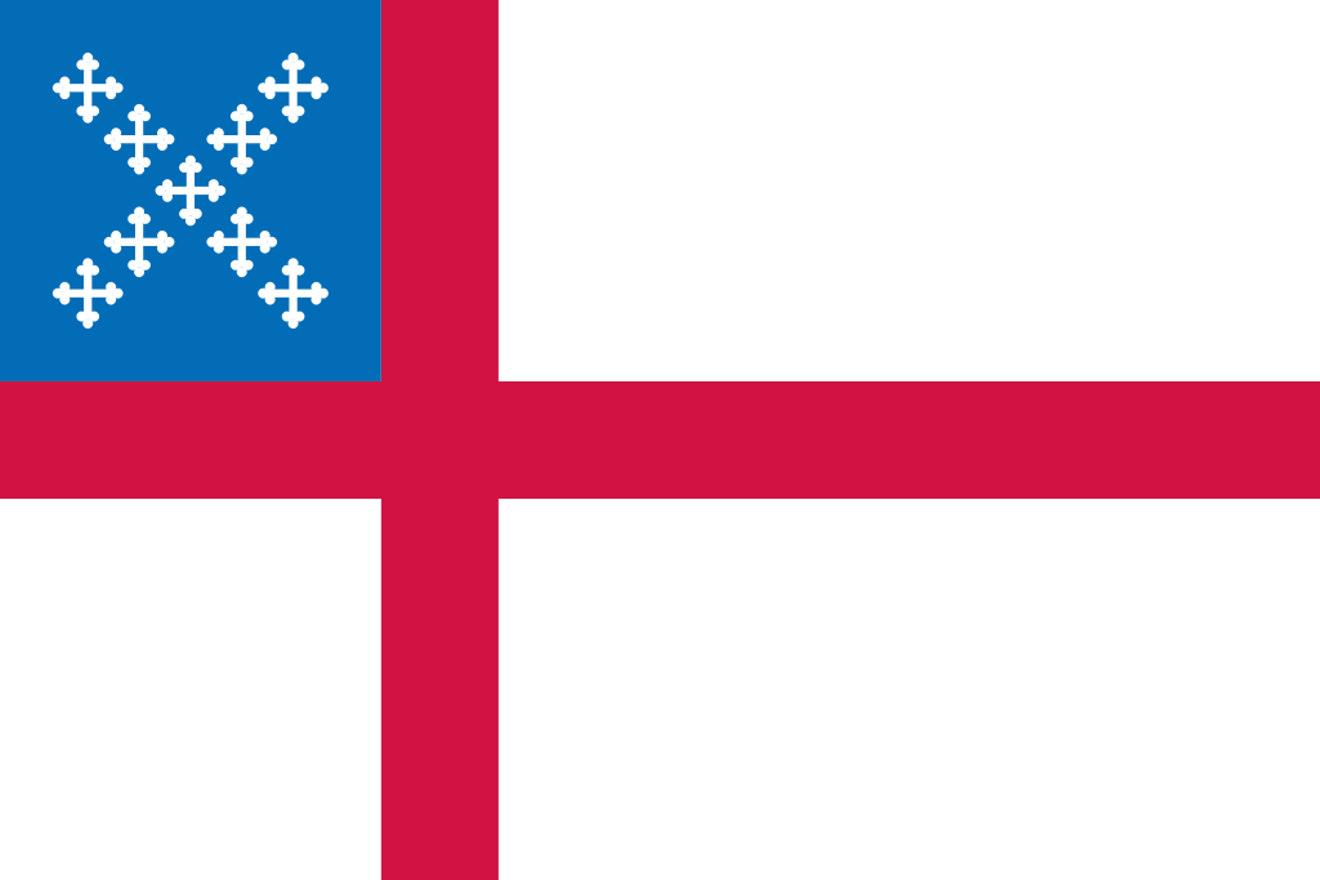

Beyond that, the facts are disputed, including even whether the Episcopal School of Dallas is a religious institution. The question is, who gets to sort them out?

For those who attended public school before the age of intolerance, a little lunchtime toking might seem like a minor thing, but the outcome in the case Doe Jr. and his dad filed against ESD could have huge implications for students, school discipline, religion and the law. So far, ESD is winning — the 5th Texas District Court of Appeals in Dallas threw the Does' case out of court last October. The Does have an appeal pending before the Texas Supreme Court, which is expected to decide soon whether to take it up.

Doe Jr. was a student during the 2014-15 school year when he made the decisions that led to his being kicked out of ESD. His father sued the school and three of its administrators, claiming fraud, breach of contract, negligence and other misfeasance based partly on the fact that the school told tuition-paying parents that, when it comes to discipline, "in most cases, students should be given a chance to redeem themselves" and that ESD is "not a zero tolerance school," according to an opinion by the 5th Court.

Doe Jr. had a clean disciplinary record, his lawyer Lawrence Friedman says, but in his case, it was one strike and out. (The Observer reached out to an attorney for ESD but did not hear back by deadline.)

The 5th Court also noted, however, that the school's enrollment agreement permitted the school to kick out students at any time at ESD's discretion.

The Does' case sat working its way through a state district court for a couple of years before ESD filed an appeal to the 5th Court claiming that the case should be tossed based on the "ecclesiastical abstention doctrine." That principle says, in essence, that since the First Amendment guarantees Americans the right to freely practice their religion, secular courts have no business meddling in questions of church doctrine or strictly internal religious affairs.

Excommunicated by your bishop? Kicked out of your Baptist congregation for bringing a flask of bourbon to church? That's none of the secular courts' business. The question of temporal meddling in ecclesiastical matters and vice versa had been the cause of several bloody European wars since about the time of the fall of the Roman Empire, so the U.S.' founding fathers wisely decided to butt out.

But the Does note that ESD is not owned or supported financially by Dallas' Episcopal Diocese. Neither its staff nor its board is required to be Episcopalian. It does not train students for seminaries, and 85 percent of its students are not Episcopalian.

ESD counters that it was founded by an Episcopalian minister, it requires students to attend daily chapel sessions, and its guiding principles are clearly stated to be Christian. As for the makeup of the student body, Episcopalians aim to be inclusive. It's Episcopalian enough to qualify under the abstention doctrine, which Texas courts interpret broadly, so how it decides to discipline its students or whom it admits to classes is not a question for secular courts to decide.

"The Does’ Petition rests on an improperly narrow view of the protections offered by the First Amendment — one that has been rejected by several Texas courts and adopted by none," the school writes in its response to the Does' Supreme Court appeal. "The First Amendment’s ecclesiastical abstention doctrine protects more than just churches and their theological disputes; instead, it protects all religious institutions and their right to decide matters of discipline, morality, and community membership without judicial interference. Here, the Episcopal School is a protected religious institution — the Episcopal faith is the reason for, and at the core of, the School’s mission. And the Does’ claims arise from the faith-based School’s request that student Doe Jr. withdraw for multiple student handbook violations — the very kind of disciplinary/membership decision the First Amendment allows a faith-based school to make without judicial interference."In their appeal, the Does claim that whether ESD qualifies as a religious institution and whether its disciplinary policies, enrollment agreement and educational practices are secular or religious are questions of fact, and under law, those are supposed to be decided by trial courts and juries, not appellate judges. The 5th Court erred in granting ESD's claims without a trial, they say.

"This Court has never decided whether the Doctrine applies to a private school claiming a religious affiliation," the Does state in their appeal to the Supreme Court. "Nor has this Court determined if the Doctrine applies when the claims implicate a private school’s 'internal affairs' — even when the evidence shows those affairs do not concern religious doctrine and instead concern false representations about the school’s secular education policies. The court of appeals held that the Doctrine applies, setting a dangerous precedent that encourages private schools to claim the sanctuary of religion to escape their express promises to parents, students, and vendors alike. As troublesome, the court of appeals’ opinion can be read to give private schools, under the guise of religion, free reign (sic) to engage in abusive discipline of students and, relying on the Doctrine, avoid responsibility for egregious behavior simply because the school claims such conduct is part of its 'internal affairs.'”

That last point is particularly troubling for the Austin-based Child-Friendly Faith Project, a charity that combats child abuse and neglect by religious groups.

"Private schools and organizations that make promises to parents about the specific care and education they will provide should not be permitted to wave the flag of religion to avoid being held accountable for the mistreatment of children through disciplinary measures," the CFFP writes in a friend-of-the-court brief supporting the Does' appeal. "This would weaken the First Amendment and expose children to harm that, in many instances, only the judicial system can redress and stop."

The CFFP wasn't alone in filing briefs in support of the Does. In 2011, the law firm Aldous/Walker LLP represented a female ESD student who, as a minor, was groomed for and led into a sexual relationship with a male teacher. The teacher was fired, and ESD gave her the same choice it gave John Doe: withdraw from school or be expelled. She sued and eventually won her case in front of a jury, which awarded her more than $6 million in damages. ESD and Jane Doe later settled the case for an undisclosed sum to avoid appeal.

"Application of the Ecclesiastic Abstention Doctrine would have had a devastating impact on Ms. Doe and, if applied in pending and future lawsuits, will certainly encourage private schools to ignore the needs of students who are victims of sexual assault or other abusive emotional and physical conduct," Aldous/Walker writes in its brief supporting John Doe Jr.

Brent Walker, one of the lawyers who represented Jane Doe, says the 5th Court's decision short-circuiting a trial on the facts in Doe Jr.'s case is out of step with previous Supreme Court rulings.

"ESD had tried to raise the ecclesiastical abstention doctrine in our case ... and it didn't go anywhere for them," Walker says. "It is simply not a school that is a church school. It's a secular school."

Walker says broadening the doctrine the way the 5th Court suggests to include ESD and its discipline policy wouldn't be good for religious freedom, either. Other organizations might "glom onto" the protection afforded for religious issues simply by claiming some sort of religious affiliation, he says.

He poses a rhetorical question: If his firm changed its name to the Episcopal Law Firm of Dallas, could it avoid any responsibility for mistakes? "Sorry, I forget to file your lawsuit," he says, but there's nothing you can do. Too bad.