She was carrying it with her in late February 2007 when she interviewed for a job in the Denton County District Attorney’s Office, determined “to make fantasy turn into reality.” She had already fulfilled her promise to get the best education, graduating from Trinity University in San Antonio and Tulane Law School in New Orleans.

Williams-Boldware landed the job and spent more than a decade trying cases for District Attorney Paul Johnson, mostly in misdemeanor court, but she had her eyes on felony court. It was a dream many aspiring prosecutors share and one of the highest positions you can reach, she says.

“Right now this fantasy may seem a little bit out of reach,” she wrote at age 13. “But I’m going to attempt to reach for the stars or go as high as I can go.”

Now it’s a dream she says she can’t reach because of her skin color. In December, she filed a federal civil rights lawsuit once again against Denton County. It came eight years to the date after she filed her first one against the county, a case she won in January 2012 only to have it slip from her grasp when the county appealed and won in June 2012.

In her current suit, she claims she has been passed over for a position up the chain as felony or lead misdemeanor prosecutor because she's black and as a retaliation for her first lawsuit against the county, the District Attorney’s Office and four prosecutors for civil rights violations.

The Dallas Observer reached out to Denton County and the District Attorney’s Office, but they declined to comment on pending or previous litigation.

“I don’t recall a time when it’s not been part of our life,” Williams-Boldware says.

Williams-Boldware’s federal courtroom journey began when a 45-year-old black woman from Dallas was caught drunk-driving through a historic black cemetery in Denton County. Debra Bagley ran over headstones, desecrating more than a few graves before a white police officer ended her spree. Bagley accused him of being a racist and regurgitated some vile comments, Williams-Boldware recalled in court documents. Bagley was arrested for a third-degree felony.

Bagley’s case made its way to the Denton County District Attorney’s Office. It was a low-profile case with a racism claim that didn’t stop with the white police officer. No black people sat on her jury; Denton County has no black judges; and the lead prosecutor, Cary Piel, is white.

Late afternoon on April 2, 2009, Williams-Boldware was preparing to leave the office when Piel, who was the misdemeanor court supervisor’s husband and a senior-level prosecutor, came into her office, plopped down in a chair and began ranting about Bagley’s case and the videos of the incident he’d watched.

“I found what she had done was pretty egregious,” Williams-Boldware said in her civil rights trial in 2012. “I let him know that I found it disgusting. I mean, she was intoxicated. She was desecrating the burial sites. I understood from the conversation that she was being very racist in her remarks to either officers or an officer. [...] He let me know that he had never heard things so … so vile before.”

Williams-Boldware recalled telling Piel that she didn’t like racism either. “He continued to talk about how vile she was and how her actions made him understand why people hung people from trees and why it made him want to go home and put on his white pointy hat,” she told the court.“He continued to talk about how vile she was and how her actions made him understand why people hung people from trees and why it made him want to go home and put on his white pointy hat.” - Nadiya Williams-Boldware

tweet this

“I felt disrespected because I didn’t understand how he thought that it was OK to come in my office and say something so vile and disrespectful and to go beyond just discussing the facts of the case. …” she continued. "So I was disappointed, I was mad at myself because having a conversation, like what do I do? I wanted to stand up and curse him out, but I knew that that wouldn't be appropriate in the workplace. It's my boss' husband, but he's not getting the point that this needs to stop and it's not OK.”

Williams-Boldware didn’t report Piel’s comment because she says she was still trying to process the ramifications doing so would have for her. She testified that she was crying and upset as she drove home and had to pull her car over because she was afraid she'd have a wreck driving the hour commute from Denton to her home on the outskirts of McKinney.

She called a coworker friend and told her what happened and sent a text to her court chief. "I said, 'I'm not going to be at work tomorrow,'" she recalled. 'I may not have a job,' and I gave him a little background as to why I wasn't going to be there, or I didn't think I was going to be there. And he responded in a 'I hope you're OK' kind of way, and left it at that."

Piel sent her an apology email and blamed his comments on the video of Bagley fighting with officers, yelling curses and racial slurs.

She did return to work the next day, but she didn't know that Piel's remarks had already been reported to her superiors.

A short time later, she met with District Attorney Paul Johnson, First Assistant District Attorney Jamie Beck and Family Law Section Chief Allison Sartin. They discussed the events on April 2, and she told them about her feelings and her anxieties.

Williams-Boldware said in court that Johnson asked her what she wanted to do, but she didn't know what to do. "In essence, I would be making a decision that affected my supervisor's husband and also a senior-level felony prosecutor in the office," she said. "I felt overwhelmed with being put in a position to make that type of a decision. He was the elected DA, and he had to decide ... what conduct he felt was best for the people that represented him."

She decided that she needed some time. She knew whatever she decided was going to affect her career. She also wanted an opportunity to speak with Piel again. "I was caught off guard that they already knew," she said.

Then the harassment began. It started with a coworker who made what she considered to be a racially motivated comment. He called her a troublemaker on more than occasion.

“I was already struggling with people knowing and what that meant for me, and to me that was an acknowledgement that anything I did from that point forward, I was going to be a troublemaker,” she told the court. “I was that girl [...] the girl that maybe was hypersensitive or people couldn’t get along with or you got to be careful what you say about — around that girl.”

She checked with her supervisor Susan Piel to make sure it was OK that she spoke with Piel's husband, Cary. Williams-Boldware testified that Piel claimed she didn't know the specifics about what had been said, but she found it hard to believe.

"After I told her what he said about hanging people from trees and wearing his white pointy hat, she asked me, 'Have I ever felt like a.... in a situation that it was us against them, and maybe that's how Cary felt when dealing with the Bagley case, that it was as us-against-them-type situation,' meaning black people against white people," Williams-Boldware told the court.

"I responded to her and said, 'Well, if I did that in my capacity as an assistant district attorney, I wouldn't be doing my job,'" she continued. "'That's not what I'm here to do. If I dealt with cases from black defendants differently than I dealt with any other case, that would be improper.' And I told her that it wasn't my job to do that, and I didn't think that that was the job of an ADA to do when assessing their cases."

Williams-Boldware said she felt that her boss was responding as a wife and not as the misdemeanor chief. "It was later used by the DA that you can't unring that bell in a conversation that I had with him about this," Williams-Boldware said in court. "That's how I felt with all of this. You can't unring it. ... I'm having all these meetings with people, and I'm a new prosecutor and I'm trying to be PC and fix it for everyone, and at the same time I'm fixing it for everyone else, I'm not fixing it for myself."

When Williams-Boldware went to speak with Cary Piel, he blamed his racist comments on his rural upbringing, his military and Texas football background and limited exposure to black people. He apologized for his comment, according to court documents. He claimed in court that he was speaking to her as a colleague and not trying to be racially insulting. He told the Denton Record-Chronicle that he "apologized over and over. I apologized five times."

She testified that his apology didn't seem genuine because he told her that she needed to get in touch with her inner feelings, as if he were blaming her for being upset. “Maybe it would make her a better prosecutor,” she recalled in court.

Williams-Boldware told First Assistant District Attorney Beck who, in turn, told her that she was working with human resources to work out what should be done. Piel had admitted to his remark during the investigation and claimed that he made a terrible mistake. They decided to send him to diversity training and ask his supervisor, Tom Whitlock, to give him a verbal warning and put the reprimand in his file.

Williams-Boldware said the situation at the DA's Office didn't change. She filed additional complaints to Johnson and eventually to Denton County's Human Resources Office, according to court documents.

Williams-Boldware decided to attend Bagley's trial and recalled Johnson attending, which she found odd since it was a low-profile case. "In felony land, it was equivalent to a misdemeanor, a DWI," she said. "I didn't see it as one of the cases that everyone converges in a courtroom to watch."

In court documents, William Trantham, a Denton-based attorney who represented Williams-Boldware, said challenges had been made in Bagley's case by the defense lawyer that black people had been struck from the jury. “Excuses are made," he said. "But no one ever reveals the racist commentary and the racist feelings of prosecutor Cary Piel at that time to the judge. It’s just silence. And so she’s kind of bothered by this. It bothers her pretty greatly. You’re supposed to reveal this stuff.”

Bagley was convicted of the third-degree felony and sentenced to two years in prison.

Still feeling like a troublemaker, Williams-Boldware claimed that she began suffering anxiety, humiliation and skin problems. Her hair began falling out because of stress, and she eventually transferred to juvenile section to isolate herself. “Of course, that transfer to that department was a dead end on her career path that she had chosen,” Trantham told the jury.

She had hand-delivered a memo to Johnson, detailing a rundown of racist remarks that had happened in the office and how they had been handled. She also reported it to human resources but later received an email from administration that stated no further disciplinary action would be taken against Piel, but another assistant district attorney would be heading to sensitivity training.

In early November 2009, she filed a complaint with the Texas Workforce Commission Civil Rights Division, but it was dismissed, according to a June 2012 Denton Record-Chronicle report. The Record-Chronicle claimed that the Equal Employment Opportunity Commission also couldn't conclude if what had occurred violated statutes, but Williams-Boldware claims that the newspaper was wrong. "They found a basis for both [of the cases] or else I would have never have made it to court," she says.

A month later, she filed a civil rights lawsuit, yet still worried about the far-reaching implications of taking her boss to court.

"It's been on applications that I've already filled out: 'Have you been involved in a civil lawsuit?" she testified in court. "I can't lie about that. I wouldn't lie about it. But it's going to follow me. I've wanted to be an attorney for as long as I can remember, and because of [Piel's] ignorance, I don't know what my path necessarily is going to look like. None of us do, but I really don't know what Monday will be like."

In Williams-Boldware's first civil rights trial, the District Attorney’s Office argued that the Piel's comments were an isolated event, were dealt with swiftly and properly and no other similar incidents had occurred since then. It pointed out that parties were thrown for her, she was given raises, promotions and even kindness was shown when she was hospitalized during a difficult pregnancy.

Thomas Brandt, a Dallas attorney who represented Denton County and the District Attorney's Office during the trial, described the misdemeanor division as sort of having "a sorority feel to it."

"Not necessarily that I'm a member of a sorority," Williams-Boldware replied. "But I do understand that it had that atmosphere."

Describing a friendly place, Brandt painted a far different picture than the hostile work environment Williams-Boldware claimed she was experiencing. He pointed out that she was involved in parties with her coworkers at work and at home. She even organized a birthday party for a coworker. "There has been no severe or pervasive harassment," he proclaimed.

The jury disagreed in June 2012, awarded Boldware $510,000 and ordered the county to pay her attorney fees. Two days after the verdict, Johnson pressured the Piels and two other prosecutors — John Rentz and Ryan Calvert — to resign."My case was dismissed. I did not testify. I did not watch the trial. I had no say in the trial. ... I was told that I didn't do anything wrong. It was an unfortunate situation." - Susan Piel

tweet this

A month later, the Record-Chronicle reported that Williams-Boldware had admitted in a sworn deposition that Calvert, who is Susan Piel's brother, never made any racist comments against her. "I always found her [Williams-Boldware] to be nice, to be pleasant, but her temperament was one of emotional sensitivity," he told the Record Chronicle.

Susan Piel didn't want to discuss this matter with the Dallas Observer. She is running for judge of County Criminal Court No. 2. Her opponent in the Republican primaries is Sean Kilgore, a former assistant district attorney from the Denton County District Attorney's Office.

"My case was dismissed," Piel said by phone Friday afternoon. "I did not testify. I did not watch the trial. I had no say in the trial. ... I was told that I didn't do anything wrong. It was an unfortunate situation."

Trantham had been riding high from scoring a half-million-dollar jury award, but in a post-trial judgment, a district judge found that Denton County wasn't responsible for current or future pain and suffering and cut the award to $170,000. Then a three-judge panel of the 5th U.S. Circuit Court of Appeals cut it to $0. They didn't agree with the jury that a hostile work environment existed and applauded Denton County's response to the incidents.

“These incidents did not involve a protracted outpouring of racially invidious harassment that require large-scale institutional reform,” the 5th Court of Appeals judges wrote, as the Observer pointed out in a Feb. 4, 2014, story. “Instead, Denton County was required to implement prompt remedial measures to prevent [Piel], and anyone else, from engaging in racially harassing conduct toward Williams-Boldware.”

Williams-Boldware appealed her case to the U.S. Supreme Court, but its justices declined to hear the case in October 2014.

"How can you excuse a trial?" Trantham asks. "You can tell how mad the jury was because they gave her $510,000."

Four years have passed since the 5th Circuit reversed the jury's verdict, and the situation for Williams-Boldware hasn't changed, she says. She reported it to the EEOC in June and received a right-to-sue letter, so she is heading back to federal court, filing what Trantham calls a "textbook lawsuit."

At first, she wasn't aware that the county had appealed her first case. She had nearly died giving birth to her son after she developed an amniotic fluid embolism, a rare but deadly complication. She fought her way through rehabilitation, learning how to walk, talk and think again. She returned to work in fall 2013 but later accepted a demotion because she says she was exhausted.

Since July 2014, Williams-Boldware has been working in misdemeanor intake and not taking part in any trials. She has been removed from the felony prosecutor track despite numerous opportunities for advancement opening, according to her Dec. 15 lawsuit.

“I went back after [the birth of her son] and watched the moves and promotion of people with less seniority,” she says. “I felt that was the plan. I was expected to give up and be satisfied that I was alive and had a job.”

In her lawsuit, she provides several examples of other prosecutors rising in the ranks while she remains in misdemeanor intake — from a white male prosecutor who was hired on the same date as she and now serves as chief felony prosecutor, to a white female who was hired after Williams-Boldware, took maternity like her and now works in felony court.

Two other white females with less experience were then promoted to higher positions within the misdemeanor court. When one of them left the DA’s Office, another white female who was also hired after Williams-Boldware was promoted to the deputy chief misdemeanor position.

But the promotion of white people over a black woman with more experience didn’t end there, according to court documents. Three more white females and two more white males with less experience were all promoted to felony prosecution.

One of the latest opportunities for the felony prosecutor track was given to another white female prosecutor who had also served in the juvenile section like Williams-Boldware. “I can almost confirm that anyone who started 10 years ago [at the DA’s Office] are all in felony prosecution,” she says.

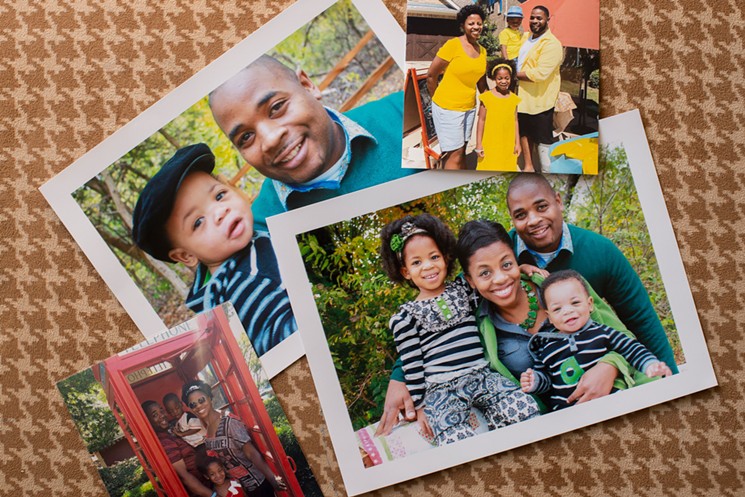

Williams-Boldware's husband, Lorenzo, died as the result of a massive stroke not long after she decided to file a second lawsuit against Denton County.

Brian Maschino

Shortly after they decided to move forward with the new lawsuit, Williams-Boldware’s 41-year-old husband, Lorenzo, was killed outside of Floyd, a small town in Hunt County. He had suffered a massive stroke and wrecked his car in early November.

They had met at Trinity University in San Antonio. He was living in McKinney, and she had moved to the area from Carlsbad, New Mexico, where she grew up with her single mother and grandparents. They got engaged and decided to settle in North Texas after she graduated from Tulane Law School. They eventually had a daughter and a son together. He worked as an electrical engineer.

They had just finished celebrating her son's scoring two touchdowns in a flag football game shortly before her husband's death.

Hundreds of people reached out to pay their condolences, and a family friend told Star Local Media that when Williams-Boldware suffered her health scare in 2013, her husband said that he wouldn't be able to get through life without his wife. "Now I think about her having to do this without him," she said.

Williams-Boldware claims that her husband had financially committed to her fight against Denton County and had taken part in the decision to file the lawsuit. He had just signed the paperwork shortly before his death. “I don’t think my husband would want me to give up,” she says. “He believed in it.”

She had thought about taking a leave of absence after her husband's death but only remained gone for a week from the District Attorney's Office. She says she couldn't sit in an empty house. "I'd lose my mind sitting and thinking about God's decision," she says.

Williams-Boldware realizes that she may not ever receive a promotion, but she claims that she isn’t just fighting for herself. “Part of my fight is for somebody else who looks like me or talks like me or was raised like me,” she says. “They won’t have to experience it and won’t be denied the opportunity after they invested their career into it.”