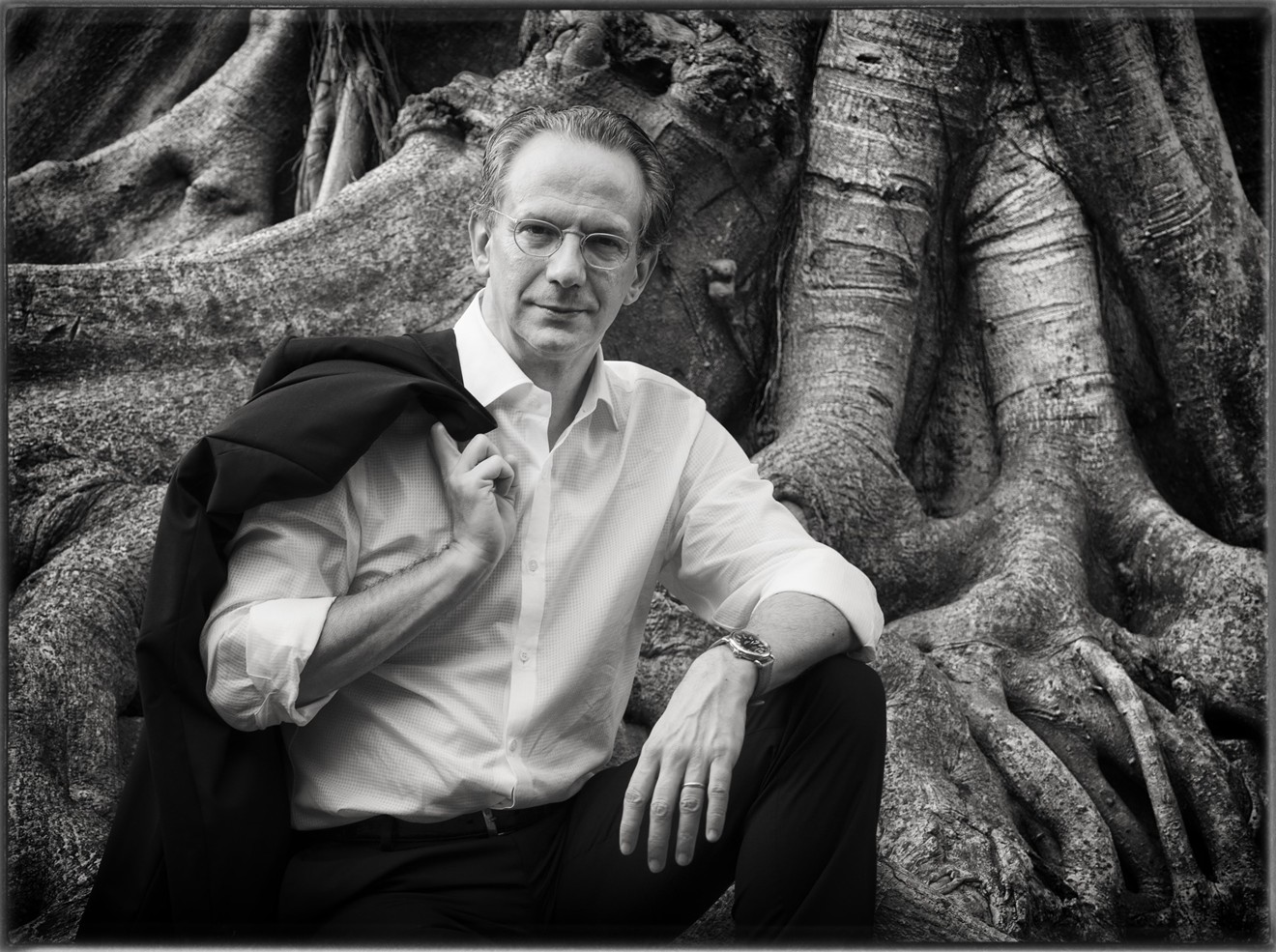

The message was clear: The DSO got their guy, and they want everyone to know it. And then Fabio Luisi arrived to prove it, leading a concert in which he, with humility, allowed the orchestra’s own extraordinary talents to take center stage.

Luisi chose the program to send a message. The first piece he conducted as the DSO’s new music director was the Poem by African American composer William Grant Still — a clear sign of his intention to expand the Dallas repertoire. Next came a concerto for seven solo players drawn from the orchestra’s ranks, allowing longtime DSO stars a chance to shine. Finally, after intermission, Luisi delivered Beethoven’s Seventh Symphony, allowing concertgoers a chance to measure his worth in the classics. Maybe surprisingly, the first half of the program was more satisfying than the second.

Still was a Mississippian who learned the violin in school and, incredibly, taught himself the viola, cello, double bass, oboe, clarinet and alto saxophone. Late in life, he became the first black man to conduct a major orchestra in the American South. He toured with a blues band before turning to orchestral music, and the influences of blues, jazz, spirituals and classic Hollywood soundtracks all come through in the 10-minute Poem. The first section is enigmatic and ominous — it feels a little like a Hitchcock movie — but the highlight came after the central climax, when the Dallas Symphony cellos got to sing their hearts out in an series of beautiful melodies woven together across the string section.

Fabio Luisi chose the program to send a message.

tweet this

Swiss composer Frank Martin was also largely self-taught, because his parents insisted he become a scientist instead. Martin flirted more heavily with elements of the European avant-garde, but much of that toughness had softened by the time he wrote the long-titled Concerto for Seven Winds, Timpani, Percussion and Strings. It’s snappier than its name suggests, with a slow movement that ominously tick-tocks away and a finale that gives the four percussionists a workout.

But the highlight was the seven DSO solo players standing in a ring around Luisi, trading riffs and solos the way boxers might trade punches. With bluesy elements, caustic wit and much egging-on, Martin’s solo parts are like a rowdy late-night conversation, and the Dallas musicians sparred flawlessly. It feels unfair to single anyone out, but clarinetist Gregory Raden and flutist David Buck are assigned especially challenging parts, and trombonist Barry Hearn’s tone, with just the right hint of vibrato, is a joy.

The Dallas Symphony had never before performed Still’s Poem and had last played the Martin concerto in 1987, but Beethoven’s Seventh Symphony is a mainstay of concert halls worldwide, including ours. (The DSO played it just a few years ago.) This was a chance for Luisi to show Dallas how he plays the hits, and he certainly presented a few big ideas. The good news is that only one of those big ideas was terrible.

Contrast, clearly, is a focal point of Luisi’s artistry. He likes playing up the differences between themes and sections; in a transition from fast to slow, or vice versa, Luisi likes to make the fast really fast, and the slow really slow. Most of the symphony, in fact, was blisteringly quick, and the DSO kept up every step of the way, delivering thrilling playing, especially in the exuberant finale, which is Beethoven at his most vivacious.

The big moment, from an interpretive standpoint, was at the triumphantly brassy end of the first movement, when, with no pause at all for the audience to clap or cough, the DSO plunged straight into the tragic slow movement. It felt like falling through a trapdoor, in a good way.

Unfortunately, Luisi’s next big idea followed in short order: playing the funeral march as slowly as possible. At nearly 11 minutes, it was probably one of the slowest performances ever attempted (most take a mere eight) and much slower than Beethoven himself preferred. This is some of the most passionate music ever written, but played at Luisi’s tempo, it feels like being dead.

But that was the evening’s only real miscue. (The Facebook stream reportedly had hiccups, too, because of a surprise rain shower.) The most important sign of all, though, was the Dallas Symphony’s enthusiasm for its new leader and the continued high standards the orchestra sets. Luisi is almost a stereotype of a conductor, with his flawless posture, purposeful body language and carried-away excitement at climactic moments. But his repertoire selection, humility and willingness to take risks — even if they fail — suggest that Dallas will find much to like in its new maestro.