The memo made public a week ago makes Hall look far worse than the cops she disciplined. It lists instance after instance in which management failed to create any kind of sane accounting system for keeping track of money used in undercover gambling investigations.“Ethics and integrity define who we are as a police department." — Renee Hall

tweet this

Whenever management did say anything about the cash used by detectives to take down illegal gambling places, what they said was crazy, all over the map and showed they had no idea what the cops were actually doing out there, some of which involves serious risk to life and limb. And that’s all in the document.

In fact, the so-called investigation of vice wasn’t a coherent investigation at all but a crazy mishmash of prior investigations, new investigations, financial audits and management reviews.

Here is an important takeaway: Investigations by the department’s internal affairs and public integrity units found no criminal behavior. None.

And remember. This comes after Chief Hall, on the job two months from Detroit in November 2017, shut down the vice unit and had all of its sworn personnel escorted out by armed police officers. Her underling at the time, Chief Paul Stokes, made it clear what they were looking for: “There could have been criminal behavior based on those allegations.”

It would have been gallant of her now to acknowledge more robustly that she and her people were wrong about that. If you don’t already know, I’m going to tell you what they actually wound up nailing these people for last week. (Stephen Young reported it all here.) Talk about a bunch of transparent CYA hogwash. Joseph Heller wouldn’t have written it in Catch-22 because it’s too unbelievable.

But first, think about this for a split second: She comes in fresh from Detroit, where a recent investigation found a “pattern and practice” of corrupt cops accused of actually going out and doing armed robberies of drug dealers. She padlocks the Dallas vice unit and exposes all of the sworn officers in it to a public accusation of criminality.

And then she investigates — for two years — to find out if she’s right.

Do you know what these cops do every day? They go undercover into illegal gaming rooms — places hidden away in warehouses, empty buildings, all over, stocked with hundreds of gambling machines sort of like slot machines in Vegas. The outsides of these place are unmarked for obvious reasons. You knock on a door and try to talk your way in.

If you do step inside, you’re in a locked cage with a guy or guys. You’re not going any farther. They wand you or pat you down for guns, knives, badges, electrical devices. They may make you pull up your shirt to look for wires. They don’t want cops.

Once inside, another guy watches you play the machines for a while to decide if you’re OK. Then the fun part starts.

The legal violation is giving something of value in exchange for a wager. But from there it gets technical and very complex. By agreement with the district attorney and by state law, a team of two detectives must establish that at least 25% of the machines in a place are breaking the law. To break the law, a machine must return a winning amount of $6 on any one bet or $15 or more on the total amount of money bet.

The cops must remember the identifying numbers of the machines they play and where they win each amount of money. But guess what? If a cop pulls out a little notebook or a phone and writes something down, he’s out of there in about two seconds and that place is vacant and swept clean in a couple of hours. So it all has to stay in the cop’s head.

Then we get into the hard part. For 20 years, the gambling cops were told to do something called “replenishing.” The city gave them about 200 bucks each day to gamble with, all taken from funds the department had seized. The odds in the gambling rooms are terrible, way worse than Vegas. You lose.

So let’s say you gamble all day with 200 bucks. But any money you win, you stick in your other pocket, because you’re going to put that money in the evidence room later. If you work it that way, you’re out of gambling money pretty fast, so you have to go back downtown and get some more money to do your 25% of the machines. And get back in.

Therefore, the undercover cops were told not to work it that way. Instead, they were told to use their winnings to “replenish” their gambling money and just remember what was what. So the accounting system, so-called, is in the cops’ heads and depends entirely on their integrity.

But, look, the whole thing also depends on their integrity, anyway. If and when a defendant takes a case to court, the only evidence is the cop’s integrity. It’s all from his or her memory and on her or his word.

Dallas Police Chief Renee Hall threw the whole department under the bus to cover her own bad decision two years ago.

Brian Maschino

But if you’re the top manager, the chief of police, then hopefully you also are aware of another more serious pitfall in questioning the integrity of the vice detectives, especially making any kind of negative definitive statement on the record. Every time they go to court to testify, any violation against them has to be divulged to defense lawyers.“A review of Vice Unit’s SOPs revealed there was only a half-page, under the title, ‘Gambling,’ dedicated to the operational procedures of the Vice Unit." — Chief Hall's memo

tweet this

Pretend you’re a juror. The vice detective is on the stand about to swear to all the machines she used and how much she won from each one and all the stuff that was going on around her. She has no notes, no photographs, no recordings. She looks pretty trustworthy.

But the defense attorney says, “Officer Doe, were you one of the detectives singled out for punishment in Chief Hall’s corruption probe after she shut down the vice unit?”

And the answer is, “Yes, sir, I was.”

Now what’s your trust level?

At a certain point prior to Hall’s arrival, a new chief of vice carried out an audit of the unit’s gambling money and decided he didn’t like the replenishment deal. A new rule was issued, verbally but not in writing, that the detectives were to stop replenishing from their winnings.

That lasted two days. Two days. Then another rule was issued, also not in writing but verbal, that they were to go back to replenishing.

The original core accusation that hit Hall’s desk as soon as she sat down from Detroit was that the vice detectives were stealing money. In two years scouring records since then, no one ever found any money stolen.

No one in the ranks believed the vice detectives were dirty. They were welcomed with open arms into other divisions — youth, sexual assault, robbery, child exploitation — where personal integrity is paramount.

Even the document in which Hall announced the disciplinary findings — the Catch-22 memo — exposed more about the failings of management than it did about the detectives: “A review of Vice Unit’s SOPs (standard operating procedures),” the memo says, “revealed there was only a half-page, under the title, ‘Gambling,’ dedicated to the operational procedures of the Vice Unit, which mainly dealt with the issuance of citations regarding gambling offenses. No other operational procedures regarding the conducting of a gambling operation were ever codified …”

Are you kidding? You send them out there. They talk their way into the cage with the guy. They get into the room and play the machines with the other guy following them around. You tell them, “Replenish.” “Don’t replenish.” “Do replenish.” You have no viable accounting system for them to use. And then you nail them on an accounting error? And not even an accounting error. A paperwork error.

Last week, Hall announced the conclusion of her now more than two-year-old investigation to find out if she did the right thing: “Ethics and integrity define who we are as a police department …” Blah blah blah.

She used numbers that the detectives themselves had faithfully recorded and filed in their own system but failed also to file in duplicate to the property room. Like, you know, the white copy goes here, the yellow copy goes there.

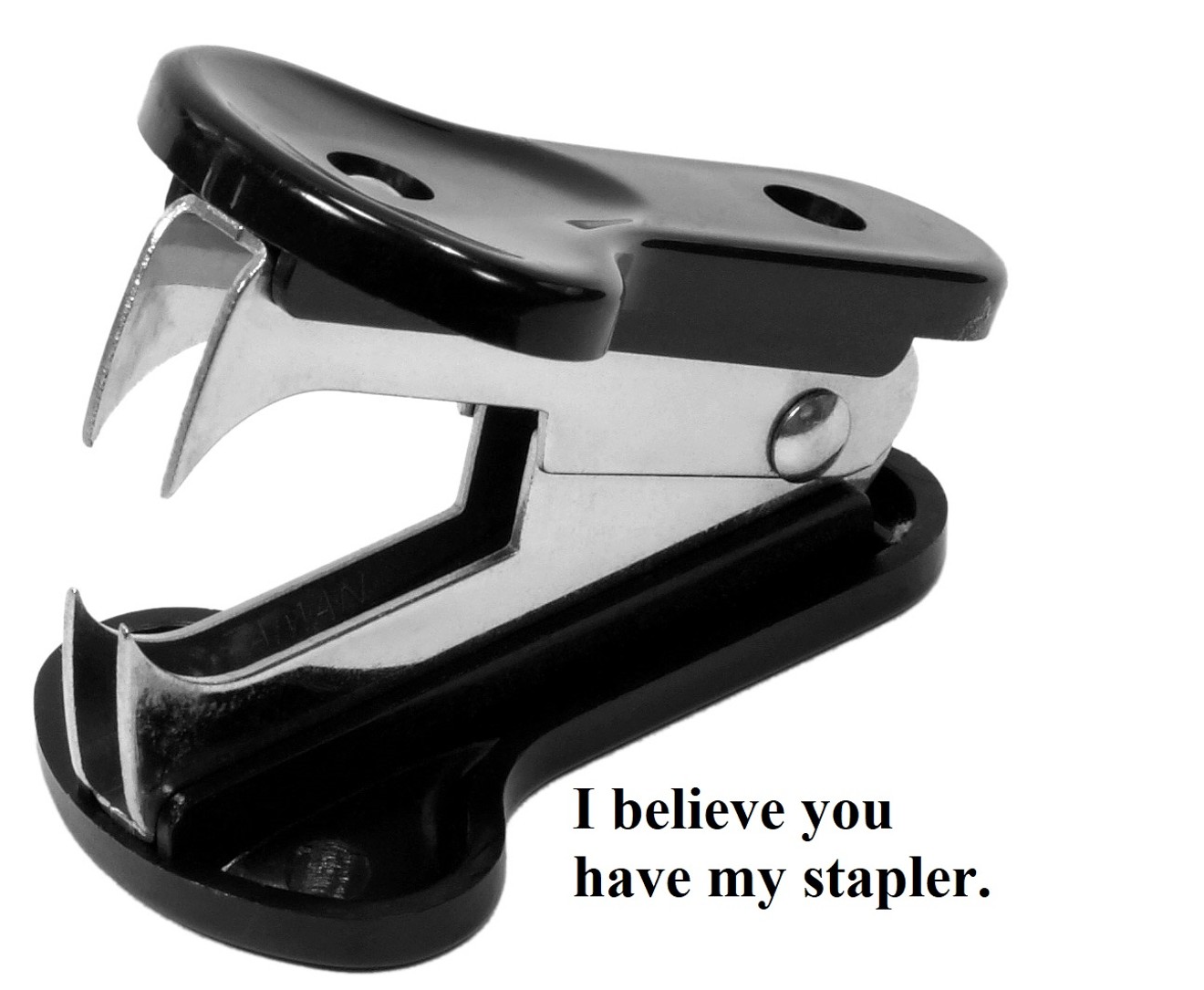

Did you ever watch the film Office Space? Then you remember Milton Waddams: “Excuse me, I think you have my stapler.” The offenses found against 17 detectives and six other sworn personnel in vice were Milton Waddams offenses.

These paperwork infractions could all have been handled as notations in personnel files that would never have been publicly characterized as punishment. In fact, that’s exactly how the first case, an officer who retired months ago, was handled, before this turned into a dog and pony show to cover Hall’s backside.

She could have said, “I was new. I was misled. I made a mistake.” She could even have said, “I was a public relations cop in Detroit, and I came here with very little actual day-to-day policing experience.” Instead with this transparently self-serving outcome, she throws the whole department under the bus to save her own bacon.

It’s too bad. She was so genuinely promising in so many ways. But I don’t know how his one ever gets forgiven. Hall has been pretty political in how she has approached the job, taking sides in the community. Now this thing, refusing to admit a mistake, trashing career employees instead, should rub us all the wrong way. Most of us have seen a stapler or two in our time.