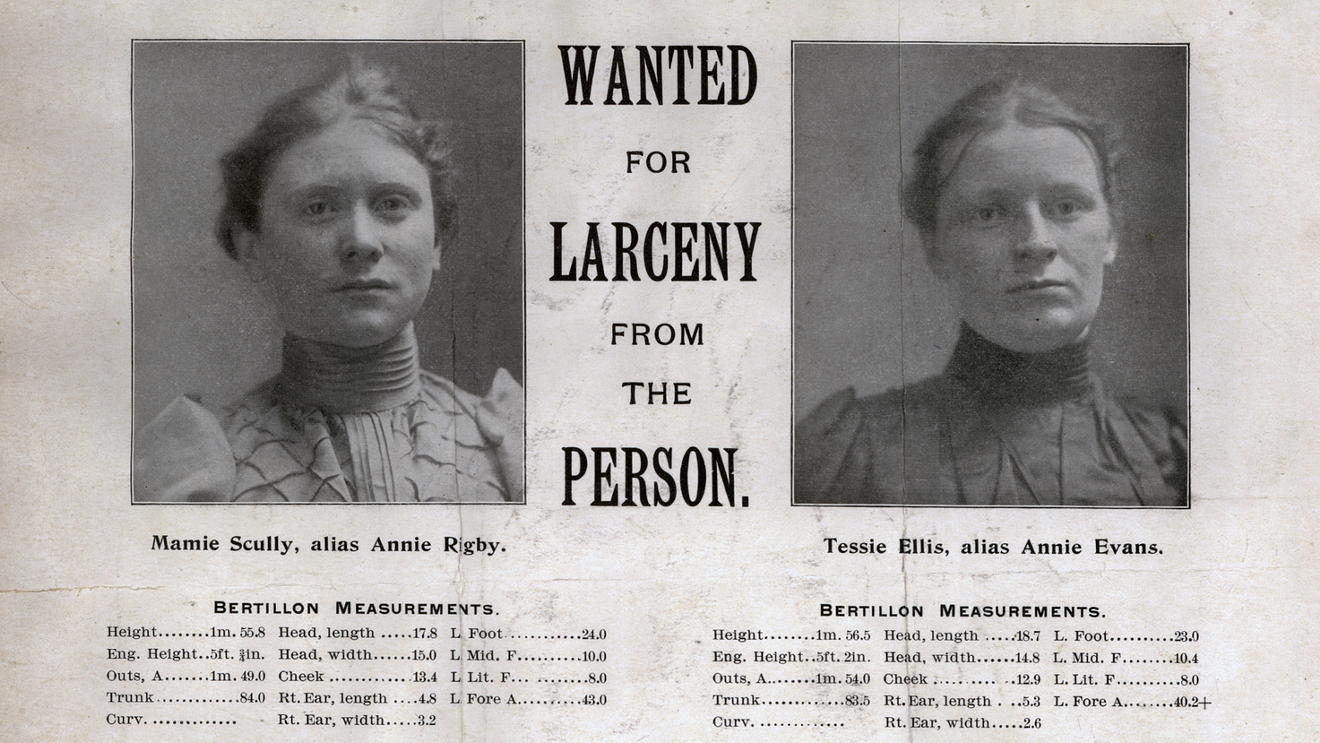

While they may sound straight from the pages of a Charles Dickens novel, the cast of characters in Wanted in America: Posters Collected by the Fort Worth Police Department 1898-1903 are actual people whose faces were emblazoned across posters of wanted criminals.

The idea for the book came about when Gene Smith, a TCU history professor, learned that Tarrant County College held a meticulous collection of historic wanted posters, detective magazines and early Tarrant County law enforcement ledgers.

“[Smith] discovered TCC archivist Tom Kellam had this wonderful collection from the Fort Worth Police Department that included not only the wanted posters but issues of the Detective magazine, which was sort of the professional publication for law enforcement, as well a number of items that came along with the collection,” says LeAnna Schooley, who co-edited the book with Kellam.

“These posters aren’t what you would’ve envisioned having seen in a movie with these burnt edges and fancy fonts,” Schooley says of the items donated by Joe D. Galloway, a retired lawman who joined the Fort Worth PD in 1936. “These were very hastily made with just as much detail as they could get on there, not worried about what they really looked like as long as they were conveying the information.”

Schooley, the executive director at TCU’s Center for Texas Studies, says more than 30 people, including herself and Kellam, wrote essays to accompany the posters in the book and provide background details.

“We proposed this collection of 50 of some of the most interesting and diverse of the posters,” she says, saying that the project took three years to complete, adding that although some of those featured were criminals, others were missing persons, even children.

One man was wanted for draining his bank account and leaving his wife and two children behind, to skip town with a younger woman; he was never found.

“Another man who lived alone was killed so someone else could steal his livestock herd,” Schooley says of another poster example. “He died violently and his body was hidden in a crevice and just barely covered over and was not found until the spring thaw. This happened in Colorado.”

In that incident, Schooley says lawmen followed livestock sales to try to trace the culprit.

“By this time, transportation was such that someone could get on a train and get across the country perhaps before they even knew who they were looking for,” she says. “[The posters] were coming into the Fort Worth Police Department from everywhere.”

Rewards ranged from small amounts to thousands of dollars and, at first, the posters contained only words. But as technology developed and reproducing photographs became less expensive, images were added.

“Law enforcement was moving along with the times as technology was available,” Schooley says. “People who wanted to be missing used it all to their advantage.”

Kellam says that, in many ways, the collection gives an account of America’s underclass.

“It was a grim era,” he says. “You have to remember there was no such thing as social services or any kind of safety net. Vagrancy was a crime.”

Pulling some handwritten ledgers from archives dating to 1873 when Fort Worth was first incorporated, Kellam ticked off listed offenses — like running a gambling joint, obstructing a sidewalk, discharging a firearm, disturbing the peace, theft, drunk and disorderly.

“The term for prostitutes was being a resident of a certain bawdy house,” he says. “There’s even a breakdown of who got what. Each department got a cut of the fine.”

The cut for Fort Worth’s mayor was about three bucks and Jim Courtright, the city marshal, received $2. The city attorney pocketed five bucks and the city secretary got $2. “That’s how the fine schedule operated,” says Kellam who went to work at TCC after spending 23 years as municipal archivist for Fort Worth.“It was a grim era. You have to remember there was no such thing as social services or any kind of safety net. Vagrancy was a crime.” — Tom Kellam

tweet this

Kellam noted that the women had almost always been charged with prostitution, shoplifting or pickpocketing.

Offenders were jailed until their fines were paid or “until they had worked off their fine or whatever,” Kellam says. “But they didn’t keep them long, because they wanted them to keep producing income for the city.”

Thumbing through the archives, Kellam pointed out that some of the cuffs illustrated in the Detective magazine looked as if they were designed to be particularly cruel. He also noted that the photos were not mugshots. Some were portraits taken of men in snazzy attire and women wearing elaborate hats. Among those on the run were “Eastern Europeans, first-generation immigrants, mainly Caucasian, African American and an occasional Hispanic.”

“There was a huge amount of bigotry and racism against everybody,” says Kellam.

There were also violent labor strikes. Street cars in St. Louis were blown up. Wretched men living on the fringes of society robbed an elderly woman. And an engineer was shot and killed during an early North Texas train robbery. For that “heinous” crime, James Darlington was caught and executed by hanging in 1899, and Kellam says Charley Ellis was never found and perhaps disappeared into Indian Territory.

At the time, “hangings were like morality plays,” he says. “They’d talk about whether [the deceased] was stoic or cowardly, what he said. They generally made a speech before the [public] hanging. It was like giving an account of a play.”

“It’s fun stuff,” Kellam continues. “It always keeps people’s attention. The stories range from funny to horrifying to grotesque.”

Schooley recalls an intriguing story about some prisoners who plotted their escape by passing notes written on sheets of toilet paper. They eventually escaped into Mexico.

“You have to remember toilet paper in the 19th century was a lot like regular paper,” Kellam says. Because many of the fugitives had multiple aliases, Schooley says research for the book was sometimes tedious. However, modern readers seem to relate to the range of crimes. Among the feedback so far, she says, are comments like “human nature is still human nature” and “some things never change.”