Her cannabis dealer, Stanton Brasher, sold weed out of a small house in a cookie-cutter neighborhood on the north side of Denton. But he was no Felix Gallardo. He wielded a keyboard and an Xbox controller instead of guns. He was more like a character from Pineapple Express, laid back from the weed he smoked yet amped up on Adderall. He kept cannabis buds in Mason jars in a toolbox in his garage, not far from the reminders that he had a wife, a former teacher for Denton ISD, and kids. The family had once moved to California, where he says he set up a legal cannabis business, but his wife filed for divorce, and he returned to Texas and his old cannabis networks.

A former actor in the Denton comedy sketch group Sketchy People, Brasher was a familiar face in the local arts and music scene, working as a freelance writer for local publications such as the Denton Record-Chronicle, the Dallas Observer and Sofa King News, an entertainment website he created with a college friend. His cannabis clients included artists, childcare workers, educators, entrepreneurs, laborers, lawyers, medical professionals and veterans.

When Peggy told Brasher about her tumor diagnosis, he understood the relief she needed. One of his clients, a published comic book author, treated epilepsy with cannabis, which medical experts from the Epilepsy Foundation say helps reduce seizures.

“So, of course, I gave her free weed for the rest of her life, which was only a few months,” Brasher told five Denton City Council members at a meeting in early November. “I would often wonder when patients like her and others would leave my house, what happens if they get pulled over? Are we going to pull a 65-year-old cancer patient out of their car, search them with the dogs, search their purse, put them in handcuffs and take them to jail, strip them, search them, make them sleep on an uncomfortable bed with a scratchy blanket, no pillow? That’s inhumane to me.”

At first glance, Brasher appears to be a solid choice as an advocate for marijuana reform in Denton. He’s an articulate college graduate with a master’s degree from Texas Woman’s University and an entrepreneur who’s owned a few small businesses. Plus, he knows the cannabis industry inside and out. He even has plans to get into the legal medical marijuana business in Oklahoma.

That last bit is the problem, though. Denton police have arrested Brasher twice for dealing cannabis. The first felony charge came in May 2018. Police raided his house and found between 5 to 50 pounds of marijuana flower. Fourteen months later, police pulled him over and caught him with, he says, about 100 illegal cannabis vaporizer cartridges. Police raided his house and found about a quarter pound of cannabis flower. They charged him with possession of a controlled substance with intent to deliver, a first-degree felony.

“And it was that second arrest that really woke me up,” Brasher says. He recalls the arresting officer telling him, “You’re 45 minutes away from a legal state, what are you doing? You can do this shit there. Stop doing this shit.”

He was facing five to 99 years in prison, but the Denton County district attorney offered Brasher a plea deal: deferred adjudication and six years on probation with 240 hours of community service. Under deferred adjudication, if Brasher completes his probation successfully, he won’t be saddled with a felony record. But navigating a term of probation cleanly is a tough proposition for anyone. About 47% of all people in Texas prisons are there because of probation and parole violations, according to the June 2019 report by the Council of State Governments.

With a felony arrest record, Brasher hardly ranks as a poster boy for the marijuana reform movement in a conservative state like Texas, where Lt. Gov. Dan Patrick refuses to allow the state Senate to even bring decriminalization bills to the floor for debate, despite wide public support for reform including from GOP members in other states who have been pushing legalization in statehouses and Congress. Given the sword dangling over his head with probation, his friends, including some at this newspaper, might suggest that the best move Brasher could make now would be to stay silent, lay low and do nothing to risk a long stint in prison.

Instead, he got a prescription for 10 milligrams of THC twice a day under the state’s Compassionate Use Program, which allows patients access to products containing CBD, a chemical in cannabis that offers some medical benefits. Brasher pursued it, he says, because his therapist thought he has PTSD as a result of his divorce, his arrests and a traumatic situation from his childhood. But his psychiatrist said it would take months to confirm a PTSD diagnosis. Then, Brasher discovered that the state's program also applies to people with peripheral neuropathy. He struggles with a form of it called meralgia paresthetica from a damaged nerve that causes numbness and spasticity in his leg.

The state-approved product is low in THC, the chemical in cannabis that gets users high, but if Brasher takes it, he nevertheless runs the risk of flunking a drug test required by his probation. On the other hand, he says, his probation also requires that he takes any prescribed medicine, so he could be damned either way."And it was that second arrest that really woke me up." - Stanton Brasher

tweet this

“I got the script mostly because I want to sleep without having nightmares and without having to take Klonopin,” he says. “However, I knew once I got it, there would be a political battle.”

In early November, Brasher mentioned his two felony convictions at the Denton City Council meeting. He offered no excuses. He had four minutes to speak to the council, which had voted 5-1 earlier that afternoon to discuss a decriminalization ordinance at a January work session. Denton Police Chief Frank Dixon has already implemented a cite-and-release policy for cannabis users who are caught with less than an ounce. Council member Deb Armintor and Decriminalize Denton, a local citizens’ initiative, want to expand it. They proposed an ordinance that would raise the amount to 4 ounces. It would also prevent officers from using Denton taxpayers’ dollars to test THC concentrates unless they’re connected to a major crime or officers discover a large amount, as in Brasher’s case. Tristan Seikel of Decriminalize Denton acknowledges that there may be backlash to the THC concentrate loophole since Texas still considers it a felony to possess THC concentrates.

“We can't let it stop the necessity for the change,” he says. “That is something to navigate (during the work session in January).”

Brasher supports Armintor’s proposal. The proposed ordinance wouldn’t have helped him out of his legal troubles, but it would have helped his former customers, some of whom are now benefiting from the Legislature’s recent expansion of Texas Compassionate Care Use Act to include more illnesses. The expansion offers people with post traumatic stress disorder or a non-terminal cancer diagnosis access to medicine that researchers claim is less addictive than alcohol, alprazolam, nicotine or opioids.

“More than half of the states in the country have a medical program, including Texas, which does see this as a medicine even if our laws aren’t quite where they need to be,” Brasher said to council members. “We can pass this ordinance and take that away and protect our youngest and our most vulnerable. On top of that, this is a bipartisan ordinance because it would save us money in our jails and our court system. It would give police less power to racially profile people of color, which is a disparity in Denton.”

***

Brasher’s case captures the odd twilight state afflicting the cannabis business in 2021. Eighteen states have legalized marijuana for recreational use, and another 13 allow some form of cannabis for medical use. (In South Dakota, voters approved legalizing both recreational and medical marijuana, but a legal challenge supported by the state’s Republican governor has stymied action.)

Despite President Joe Biden's promise on the campaign trail, weed is still illegal on the federal level, though an on-and-off-again Justice Department policy against strict enforcement in states that have legalized it is on again for now. Businesses in states were marijuana is legal still have limited access to banks, however, because of federal anti-money laundering statutes. A limited measure in Congress to fix that problem is being blocked by Senate Democrats who insist on a broad decriminalization bill they say would help correct disparities in past enforcement that has unfairly targeted “communities of color.” Republican lawmakers are unlikely to support a broader bill, so the likely outcome is that Congressional Democrats will once again choose a big, perfect failure rather than succeed at passing merely good, limited reform.

Back at home, meanwhile, it’s now legal for farmers to grow low-THC hemp, but enterprising chemists have begun using CBD from legal hemp as chemical feedstock to synthesize variants of the THC formula that they contend is legal, though state authorities in Texas disagree. Reputable companies are calling for regulation to ensure the safety of synthetic TCH isomers, and both the FDA and Centers for Disease Control and Prevention warn that the unregulated products may be unsafe, but the odds of any agency stepping up to regulate the safety of an illegal product are virtually nil.

On the local level, the consequences for being caught with a small amount of cannabis vary depending on the amount, the location, the police agency doing the arresting and each officer’s discretion.

It’s entirely likely that anyone involved in the marijuana industry anywhere, whether buying or selling, is violating or has violated some law, somewhere. So, Brasher’s situation is not particularly surprising, though his willingness to step up as an advocate seems risky.

Of course, the confusion and unfairness in today’s marijuana scheme is hardly surprising, considering how hypocrisy and lies were baked in at the very start of the nation’s War on Drugs.

Fifty years ago, when President Richard Nixon declared war on cannabis, he probably didn’t consider how it would affect veterans of the Vietnam War or future real wars. He simply wanted to get “the public to associate the hippies with marijuana and Blacks with heroin, and then criminalizing both heavily, we could disrupt those communities,” John Ehrlichman, Nixon’s former White House counsel, told journalist Dan Baum in 1994, according to an April 2016 Harper’s Magazine report. “We could arrest their leaders, raid their homes, break up their meetings, and vilify them night after night on the evening news,” he said. “Did we know we were lying about the drugs? Of course we did.” (Ehrlichman lied about many things, though, and some historians point out that Nixon’s version of the drug war was generally more oriented toward public health than later administrations’.)

But Nixon’s war, along with future Republican and Democratic presidents’ perpetuating it, has led to more than 550,000 cannabis arrests each year and nearly 500,000 people incarcerated for drug law violations, according to a June 2021 report by Vera Institute of Justice. In 2018, about 100,000 of those arrests were in Texas, with 80 percent of those people arrested for low-level possession, NORML, a nonprofit advocacy group, reported in 2020.

Despite rates of drug use and sales similar across ethnic and racial lines, the Vera Institute points out that “Black and Latinx people are far more likely than white people to be stopped, searched, arrested, convicted, harshly sentenced, and saddled with a lifelong criminal record.”

In 2018, 40% of U.S. drug arrests were for cannabis offenders, Pew Research reported on Jan. 22, 2020. In fact, every 58 seconds, law enforcement officials are arresting someone, somewhere, for a cannabis offense, according to drugpolicy.org.

War veterans are among those being picked up.

***

For nearly a decade, retired Army Maj. David Bass worried he’d be one of those veterans. He’d been using marijuana he bought from cannabis dealers to deal with PTSD. He didn’t like the painkillers his doctors at the Veterans Administration hospital were prescribing. The pills, he says, left him emotionless with suicidal ideation. At 64, he spent 25 years in the Army, becoming a veteran both of Desert Storm and Operation Iraqi Freedom. When he left the service in 2006, nightmares of battle haunted him for several years before Bass sought help. A Fort Worth native who lives in Killeen, he says that he still has the sensation of being in Iraq. He can hear the rockets launching and exploding all around him.

Bass started taking painkillers and psych meds to cope and then discovered the medicinal benefits of cannabis.

When the Observer first spoke with him in January 2017, Bass was spearheading a new mission for Texas Veterans for Medical Marijuana, an advocacy group, along with lobbying groups Texas NORML and the Marijuana Policy Project. They called it “Operation Trapped” in response to how Bass and other veterans were feeling about not having access to medical marijuana to treat their injuries and trauma.

They were supporting Sen. Jose Menendez’s SB 269, which sought to expand the Compassionate Use Act and allow any Texas resident with a doctor’s recommendation access to medical marijuana. The original act, they claimed, had left out more than 1.7 million Texans who could benefit from medical marijuana. They wanted to increase the number of medical conditions that qualified and allow patients access to the whole plant, not just low-THC oil.

“The opioid medication was addictive, and the psychotropic drugs had terrible side effects,” Bass wrote in a letter to Lt. Gov. Patrick in May 2017. “I researched medical cannabis and discovered that thousands of veterans testify that cannabis is effective for chronic pain and PTSD. I found out for myself that it is effective to relieve my chronic pain and the symptoms of PTSD.

“Unfortunately I am labeled a criminal in our state because I choose to use cannabis. I am not a criminal. I am a retired military officer, a homeowner, a taxpayer and a voter.”

On Sept. 1, Bass and other Texas veterans finally accomplished part of their mission when House Bill 1535 went into effect. The Legislature expanded the Compassionate Use Act to cover people with PTSD and cancer patients, not just the terminally ill ones like Peggy, who died shortly after Brasher started giving her free weed.

Bass, who is the director of veteran outreach for Texas NORML, has been taking medical marijuana for a couple of months now. It feels good, he says, finally to be under a doctor’s care. His doctor is a Navy veteran and, Bass says, one of 440 Texas doctors who are able to prescribe low-THC medicine under the Compassionate Use Program, one of the most restrictive in the country, according to the National Conference of State Legislatures."Unfortunately I am labeled a criminal in our state because I choose to use cannabis. I am not a criminal." - David Bass, retired Army major

tweet this

“When I used it illegally from 2012 to September 2021, I wasn’t using it under a doctor’s care,” Bass says. “It was just me figuring out on my own and speaking with other veterans to find how to use it and how it helps. One of our key objectives [with Operation Trapped] was to be able to use cannabis under a doctor as part of a long-care medical cannabis program.”

Despite the state labeling the program as low THC, Bass says cannabis manufacturers follow the same 10 milligram per dose standards as manufacturers in other medical cannabis states. The law allows the two companies licensed for manufacturing medical marijuana, Texas Good Blend and Texas Original Compassion Cultivation, to make products with less than 1% THC by weight, which, Bass says, allows them to create gummies containing up to 10 milligrams of THC, a common therapeutic dose in states with legal medical marijuana.

“That is a strong dose for the average person, and is effective for most people,” he says.

Bass says he believes that within the next few months, the companies will be able to formulate 20 milligrams for veterans and other patients who need stronger medication.

Bass was smoking about a half gram of the flower in the morning and in the evening. Now he’s using 5 milligrams of CBD and 5 milligrams of THC in the day and zero milligrams of CBD and 10 milligrams of THC in the evening before he goes to bed. It’s working for him, he says.

And while he’s grateful for the expansion of the law, Bass points out that it’s only caused more problems legislators need to address. For example, chronic pain sufferers must choose between painkillers or medical marijuana. “Pain doctors will not allow them to use both,” he says. “That isn’t just a state issue but a federal one.”

VA doctors also won’t prescribe cannabis since the federal government still hasn’t decriminalized it.

Since the law went into effect Sept. 1, Texas veterans have been calling Bass for advice and to report issues with local school districts that are discriminating against their children. One veteran’s child received a prescription for medical marijuana, but school officials wouldn’t allow her to take the medication on school grounds. It didn’t make much sense to Bass, who’s a former school teacher, because he knows of students who were prescribed controlled substances and allowed to see the school nurse who would administer the narcotics.

He’s also been receiving calls from veterans who are on probation but now qualify for medical marijuana in Texas. They are worried that they will be violating their probation if they begin taking it and fail their drug test.

“These are all big issues that we have to talk to our legislators about in 2023,” he says.

Brasher, meanwhile, isn’t waiting.

***

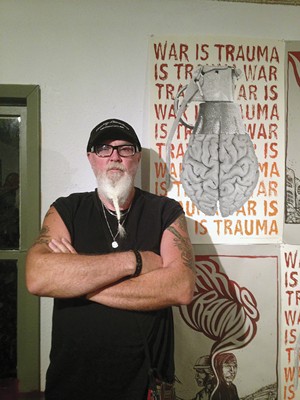

Stanton Brasher has been discussing decriminalization of cannabis with Denton council members.

Mike Brooks

They also discussed the proposed decriminalization ordinance. “As a judge, I don’t get to have an opinion, so council gets to do what council does,” Atkinson said. “And if that’s what the local community wants to do, then that’s fine. It’s either that council member Armintor’s [proposed ordinance], or we come up with a program that’s a model for the state on how to handle the ticket once it’s written because we still got UNT. So the kid might read in the newspaper, ‘city of Denton legalizes marijuana.’ But UNT PD is not on board with that. They’re still going to give out tickets to their students and arrest them. So will TWU.”

Dixon’s cite-and-release policy for people caught with small amounts of marijuana is the next item of discussion. Atkinson said the chief's policy is working. He’s seeing fewer low-level cannabis offenders, only about a handful since he took over as a magistrate in June 2020. It’s far less than what he was seeing as a magistrate in Tarrant County, where police would take you to jail if they caught you with a joint.

But not anymore. In June, Tarrant County officials implemented a cite-and-release policy similar to Denton’s. Azle’s police chief, Rick Pippins, said in a late June announcement, “The search for improvement in the criminal justice system is a continual process. Police, prosecutors and courts always seek to improve the fairness, accuracy and speed of the system, which benefits all stakeholders, including the accused.”

Brasher wants the courts to improve the fairness of probation now that legislators have expanded the Compassionate Use Program. His doctor gave him a prescription for medical marijuana yet, if he fills it and takes it, his probation could be revoked and he could spend the rest of his life in prison.

“My probation also says that I have to use my medication,” he said. “So I got this prescription and I’m in violation of my probation if I don't take it.”

Atkinson laughed. “I see. Have you talked to your probation officer about it?”

“He kind of giggled and was like, ‘I don’t think they’re going to go for that, but I’ll ask my supervisor,” Brasher replied. “She basically said the same thing. ‘I don’t think they’ll go for that. If you want me to go higher up, I can.’ I talked to my lawyer, and he laughed and said that’s true.”

“That’s just like terms and conditions,” Atkinson says. “That’s just the way it reads.”

Brasher nodded slightly. “One of my biggest arguments is that I could have been a meth dealer, but if a psychiatrist gives me Adderall, I have to take it.”

Atkinson nodded in return. “Yeah, they would be OK with that. It’s normalized.”

“In Oklahoma, if you’re on probation for anything, but you have a medical condition that requires cannabis, you can take it,” Brasher says. “It’s written into the legislation. Our legislators haven’t written anything in there. My lawyer was like, ‘Well, yeah, if you want to retain me for another $1,500, I could go talk to the judge for you.’”

Brasher says he doesn’t have the money to retain his attorney again, and probably couldn’t afford the medical marijuana even if the judge would allow him to use it. Texas’ medical cannabis prices are about 50% higher, Bass says, than our neighboring states where whole plant medical marijuana is available. Bass is spending between $400 and $500 a month for his cannabis-infused gummies and CBD oil. Part of the reason it’s so expensive is because Gov. Greg Abbott won’t allow brick-and-mortar dispensaries. Then, there’s Texas DPS’ rule about only storing the THC medicine overnight on the drug manufacturers’ premises. It requires drug manufacturers to hire drivers to deliver their product to the far reaches of rural Texas.

This is why Bass says cannabis dealers like Brasher once was aren’t going out of business in Texas anytime soon. It’s cheaper for people to buy the cannabis flower on the underground market or to keep taking their painkillers.

Bass hopes to change that at the 2023 legislative session. “Our ultimate goal,” he says, “is to legalize cannabis in Texas because Texas Veterans for Medical Marijuana do not believe anyone should be arrested for cannabis whether they are using it as a medicine or a way to relax after work.”