In a baseball cap and sensible shoes, Menchaca rummaged through his vehicle, where he kept several weapons stowed in case of roadside conflict: an ice pick, two survival knives and two machetes, to name a few. They had saved his life before, he insisted, and even at 81, Menchaca never backs down from fights.

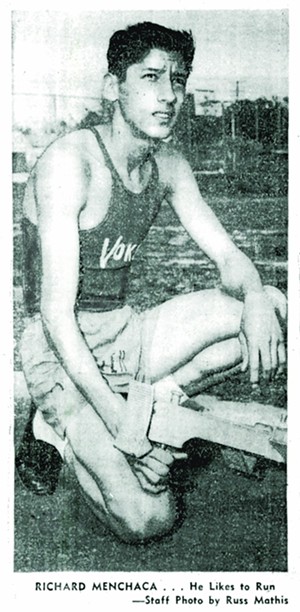

The pepper-haired professor grabbed a plastic bag full of jangly, spherical cat toys and tucked a statue of an eagle under his arm, both of which he’d use to illustrate key points during his lecture. Then, he began the trek down the hill, past the fountain-filled lake, up some 25 steps and into the near-empty brick building. Menchaca was a state track champion in high school, and he once ran 49 miles for his 42nd birthday. He walks fast for a man his age.

The halls at Cedar Valley were hushed that Tuesday. Menchaca stopped by the office of a colleague and exchanged pleasantries, but soon enough, the talk turned to the conflict that had been festering behind the scenes. Like many others, the men believed that Dallas College hasn’t been the same since it was restructured. What was once a district comprising seven independently accredited colleges, Dallas County Community College District (DCCCD), had merged under one name in 2020 to become more streamlined, updating both its outward brand and internal operations.

Some professors supported the shift to the school’s “one college” model, but Menchaca had accepted his new role as the face of the resistance. Critics say he's a troublemaker who’s clogged the wheels of progress. Supporters laud him as a principled maverick.

In 2020, as the pandemic upended life, many workers suddenly faced unemployment. Soon, cuts crept into Dallas College’s roster and hundreds of employees were laid off. Four hundred forty-six of them signed nondisclosure agreements (NDAs) to receive severance pay, costing the county taxpayers more than $12.3 million, Menchaca said. Some who had openly opposed the changes reported that they were retaliated against. Certain older professors at odds with the administration claimed they’d received grueling teaching schedules and suspected it was a calculated move on the school’s part."It’s no longer an educational institution. It is now a corporation." - Richard Menchaca, professor

tweet this

Last year, Menchaca led a group of full-time faculty in voting on a resolution of no-confidence in the school’s chancellor, Joe May. More than 71% of professors who voted endorsed the resolution. It was the second-largest voter turnout of full-time faculty in the college’s history, Menchaca said. At the time, a Dallas College spokesperson pointed out the vote gauged only a portion of faculty members because it left out adjuncts and part-timers. In response, Menchaca and company have accused the school of trying to spin the narrative.

Other media outlets have covered the controversy unfolding at Dallas College. Last summer, FOX 4 reported that one online course didn’t list the professor’s name or provide any lectures.

The Observer has heard from numerous professors and students worried and upset by the restructuring, yet few were willing to speak on record. Menchaca described a chaotic and stressful work environment. Chaplains have been sent to campuses, as have therapy dogs.

Many faculty are terrified of losing their jobs in a state that’s turned increasingly combative toward academic freedom. But some have bolstered Menchaca’s claim of a toxic work environment, where, they say, professors are encouraged to prioritize “student success” over quality education. That success is measured by the number of transfers, degrees and certificates produced, and successful students mean that May would pocket a $100,000 annual bonus, Menchaca said. Earlier this year, the Observer requested interviews with May, then-Executive Vice Chancellor Justin Lonon, and each member of the Dallas College Board of Trustees, all of whom either didn't respond or declined to comment.

Dallas College, some fear, is morphing into a degree mill. And Menchaca longs for a return to the old school. “I would like to go back to the way education was,” he told the Observer in April. “It’s no longer an educational institution. It is now a corporation.”

***

Still, the administration enjoys the support of some faculty members. Years ago during May term, Matt Hinckley was approached by a student who burst out in tears. The student explained to Hinckley, who at the time was an instructional associate at one of DCCCD’s journalism departments but now teaches history, that someone in her family had just died. Now, she was looking to turn in her work but her professor was nowhere to be found, and she feared failing her class. Some offices had been closed for training, and even the dean wasn’t there to speak with her. This kind of thing happened often, Hinckley recalled.

To him, it was one example of how easy it is for students to become discouraged, potentially leading some to drop out and never return to higher ed. Others never enrolled in classes at all. As the son of a former dean in a Chicago-area community college, Hinckley understands how essential education is. A self-described “community-college lifer,” Hinckley has at various times been a student, a staff member and a low-level administrator at DCCCD. He’s also been an adjunct and full-time professor, and the faculty association president at both the campus and district levels.

Hinckley believes that before the restructuring, DCCCD made some students’ dreams come true. Still, there were so many more who didn’t receive the help they needed. They either fell through the cracks or never got to the school in the first place. “Call it death by 1,000 papercuts,” he said.

It could be difficult to make progress to benefit students before, Hinckley explained. Sometimes, when a change needed to be made, leadership at one of the seven accredited schools might dig in their heels and claim independence, making it harder for the district as an institution to advance. The same might happen if a campus sought to make an adjustment but was blocked by district middle management. This back-and-forth also bred a work culture that lacked accountability, he said.

For many professors, Hinckley represents one of the faculty’s biggest restructuring advocates, with some critics going so far as to describe him as a “lackey.” There’s even a rumor floating around that Hinckley’s father and Joe May are golf buddies, which he firmly denies. He admits that restructuring has been tough, but he understands the impossibility of a seamless transition for a change of that magnitude. It’s sort of like remodeling a 50-year-old home, he said: “When you start tearing down walls, you’re going to find all sorts of things with your house that you didn’t know were there.”

One can’t really disentangle the consolidation from the COVID-19 pandemic, which itself took a toll on the college’s operations, he said. The pandemic also made it harder to settle disagreements because the professors weren’t around to talk through things in person. If COVID hadn’t hit, Hinckley isn’t sure the vote of no confidence in May as chancellor would have manifested, which he believes ultimately worked to blemish the faculty’s reputation."I don’t have rose-colored glasses about the past in the way that some people do." - Matt Hinckley, professor

tweet this

Still, at least one former employee has sued Dallas College over claims it used “restructuring” as a pretext to illegally fire him.

Hinckley sees benefits to Dallas College’s new structure. The school now provides textbooks for students, a cost that’s included in their tuition. In years past, many students never bought the books, which sometimes weren’t accessible until later in the semester, he said.

Hinckley acknowledges there are threats to public education, but he doesn’t think they’re coming from Dallas College’s district office. It’s the anti-vaxxers, anti-critical race theory zealots and politicians opposed to public education who should be the targets of the faculty’s derision, he argued.

That’s not to say that things are perfect at the school, but Hinckley emphasizes the importance of continuously striving for improvement. “I don’t have rose-colored glasses about the past in the way that some people do,” he said. “I don’t think the past for which some of my colleagues yearn was as great as we thought it was.”

***

Justin Lonon’s parents didn’t finish college, but earlier this year, he took over as Dallas College chancellor after May retired and transitioned into a role as chancellor emeritus. Growing up in a small town in the hills of northern Arkansas, Lonon appreciates the power of education and believes that internships can mold students’ career arcs, he said during a 2019 interview with Jacob Vaughn of the student newspaper Brookhaven Courier. (Vaughn now works as a staff writer at the Observer.)

Lonon applauded DCCCD's efforts over the years to provide wraparound support and social service needs outside the norm. To remove barriers to transportation, the school negotiated with Dallas Area Rapid Transit (DART) to offer free passes to all students taking six hours or more, he said. They also worked with a local food bank to install pantries at each college, ensuring that students had access to fresh produce.

But DCCCD’s seven-college structure was problematic for students, Lonon said at the time. One issue was the confusing information that existed among the colleges, each of which was independently accredited. Campuses had separate websites and departments, making it hard for students to navigate between schools.

Ultimately, the board of trustees opted to pursue a single accreditation. “This one college thing will cause some alignment and do away with some of those inconsistencies that exist,” Lonon told Vaughn at the time, “and hopefully better prepare us to serve students and ensure that our own structure is not getting in the way.”

Yet some students say the new structure has gotten in the way. David Hill, 50, owns the Texas Best Flooring Company. He eventually wants to become an attorney but chose to enroll at Dallas College to get a construction technology degree so he can effectively cross-examine general contractors and others. Hill said he’s attended seven universities throughout his life. He insists that “none of them are as bad as this.”

Hill said he has a 4.0 GPA and takes school seriously but claims that Dallas College isn’t setting everyone up for success. Students now “run all over the program,” Hill said, and he thinks Dallas College’s current emphasis on digital testing and textbooks has hamstrung critical thinking. Students can use a simple computer search to quickly pluck answers straight from the digital books, ensuring that they earn an A. ("Dallas College has been unable to find evidence supporting the claim of a loophole in our online testing or our textbooks," a spokesperson told the Observer by email.)

But in the world of construction, Hill fears a watered-down education could lead to real disasters. Dallas College’s construction graduates may someday build skyscrapers with this knowledge, and Hill said he certainly wouldn’t hire many of his own classmates. “Students are used to getting trophies for showing up, and some of that is part of the culture now,” he said. “But in construction where people can die because you did something wrong? People need to realize how serious things are.”

At Dallas College, political correctness takes precedence while qualified professors are “getting fired left and right,” Hill continued. Chaos behind the curtain always bleeds into the foreground.

Hill claims that administrative incompetency has stalled students’ ability to graduate. Some have had to wait five years to receive an associate’s degree. Other students simply give up and “disappear.” They’ll sometimes vow to return when they can again afford classes, a promise that Hill thinks few will actually fulfill. Dallas College’s graduation rate is relatively low. According to the Department of Education, 9% of its students earn a diploma there while the national midpoint for two-year schools is 29%. Its graduation rate also falls short of Collin College’s 14%."Students are used to getting trophies for showing up, and some of that is part of the culture now." - David Hill, student

tweet this

Hill insists he should have already moved on to law school this year but the administration kept canceling the classes he needed for his degree and introducing new bureaucratic hurdles. Since 2019, he swears, he hasn’t received a single reply after emailing the school. By the time Hill does walk the stage to accept his diploma, he estimates that only a handful of his classmates who started in the same semester will be there to join him. “So many students just gave up, walked away without a degree,” he said. “There’s just so many ghost students out there.”

***

Despite his ongoing scuffles with the school, Richard Menchaca was laser-focused on delivering an engaging lecture during that day’s integrated reading and writing class. Around 15 students sat beneath the fluorescent overheads as he produced the cat toys and the eagle statue. One by one, the colorful jangly plastic balls were tossed to students, who were told to repeat the affirmation: “Because I can and I will.” Menchaca told his pupils how proud he was of them. Some needed that extra bit of encouragement.

The professor also opened up that day, saying he’d lived through hell for the first 21 years of his life. His father was an abusive alcoholic, but the violence he’d experienced wasn’t just at home. Growing up in his San Antonio neighborhood, Menchaca said he’d witnessed many murders executed with shotguns, machetes and knives.

But rather than falling into a life of violence, Menchaca discovered an opportunity to make something of himself. In high school, a track coach saw something in the troubled youth and pushed him to become a state champion. Menchaca credits his coach with saving his life. Eventually, Menchaca would be inducted into multiple athletic halls of fame.

Many of his students had also survived trauma, but Menchaca insisted they could overcome any hurdle. There were nontraditional students who were returning to school after encountering hardship. Some had lost their closest loved ones. One young man told the class that he’d been sucked into the wrong scene, which led to him getting robbed at gunpoint and pistol-whipped one day. In a case of self-defense, he shot and killed all three home invaders. The experience inspired him to get his life back on track.

At one point during his lecture, Menchaca turned to the eagle statue he’d carried in with him. He told his class that it was a symbol of strength and the mascot of his alma mater, North Texas State University (now the University of North Texas). Referencing a popular myth, Menchaca told his students that all aging eagles must face a decision at some point during their time on Earth: whether to keep living or to give up and die.

“If they choose to die, what’s going to happen?” Menchaca asked.

“They die,” his class replied.

That’s right, Menchaca agreed.

“If the eagle decides to live, they will go up to a mountain perch where it’s safe and start pecking away the old feathers. And from what I understand it’s very painful,” he said. “When they do that, they wait. They endure — until they get back their feathers, and then they fly again.”

***

With his shock of white hair and ink-black glasses, Tommy Thompson trod up to the lectern. It was Nov. 9, 2021, and the Dallas College Faculty Association president felt compelled to speak to the board of trustees, even though speaking at board meetings wasn’t exactly his style. He assured members of the board that many faculty understood the magnitude of the school’s transition and said there was support for certain changes. Yet Thompson feared that one proposed move would damage the school: the elimination of three-year rolling contracts.

Three-year rolling contracts at Dallas College mean that for the first three years of their time with the school, faculty are given one-year contracts, The Et Cetera student newspaper reported in October. After that, they’re granted a three-year contract which renews each year, one that can’t be ended without a hearing, retirement or death.

Some board members believed that these contracts made it too difficult to part ways with problematic professors and attract new talent. But Thompson worried that dropping the rolling element could drive gifted young teachers to colleges with better job security. “Losing our competitive advantage in recruiting and retaining faculty will have a direct impact on student success, as well as our work to ensure our diverse student body are able to see themselves reflected in the faculty who teach them,” he said at the time.

Despite faculty protest, the board voted to eliminate such agreements on Jan. 11. Faculty morale had been dampened with feelings of “defeatism and disappointment,” Eastfield Campus Faculty Association President Andrew Tolle told the Richland Chronicle, another Dallas College student paper. And even though Menchaca may have been one of the vote’s loudest critics, he wasn’t the only one who thought it would work to stifle academic freedom. “We live in a time when professors are often targeted by political movements,” Tolle said, “and the only thing that allows faculty to teach the truth — no matter how unpopular that truth is during any fleeting political moment — is the knowledge that they will have a job after that semester.”

These bygone contracts were Dallas College’s version of tenure. Shedding such agreements is part of a broader shift away from the traditional model of professors serving on continuous appointments with tenure, said Mark Criley, a senior program officer with the American Association of University Professors (AAUP).

Critics say higher education has become increasingly commodified. President Neil Matkin at nearby Collin College, for instance, has boasted of higher ed’s “Amazonification,” whereby students are treated as customers and education as a product.

Criley is familiar with a different yet similar term: “adjunctification,” meaning administrations’ increasing interest in hiring faculty piecemeal, sometimes just for part-time or temporary positions. It may be done in the name of cost and accountability, he said, but adjunct professors would no doubt better serve their students if they weren’t in such precarious professional positions.

Texas is particularly hostile toward tenure. Earlier this year, ahead of his primary race, Republican Lt. Gov. Dan Patrick vowed to revoke the protection for certain professors, drawing condemnation from educators nationwide. Patrick’s announcement was the latest in a series of crackdowns on academic freedom, with politicians attempting to banish what they see as the threat of “critical race theory” and LGBTQ+ inclusivity in class.

Eliminating tenure allows administrators to hire multiple adjunct professors to do the same thing for a fraction of the cost, said Chris Macaulay, an assistant professor of political science at West Texas A&M University. Some tenured professors may earn up to $70,000 a year teaching three or four classes. Conversely, more than half of adjunct professors (53%) have a per-course rate of less than $3,500, according to career website Zippia.

Since adjuncts make so much less than tenured professors, they also have to teach more classes to get by, Macaulay said. Getting rid of tenure could potentially lead to professors who are stressed out and stretched thin, which may further ding the integrity of instruction. Some faculty may also teach several online courses, which are the better choice for certain students. “But it runs the risk of becoming a degree mill,” Macaulay said. “A way to just crank out classes, crank out units, crank out students with less effort and less quality to achieve the same goals.”

Online education is becoming increasingly common, but Dallas College may be on the forefront of a new trend. Jeff Blodgett, president of the AAUP Texas Conference, said he’d never heard of NDAs in academia until now. Suddenly facing unemployment amid a pandemic, the 446 employees who reportedly signed the nondisclosure agreement were effectively vowing to never criticize their former employer on social media or even job sites like Glassdoor and Indeed. They also agreed to never privately sue the school, even in cases with claims of discrimination based on sex, age and race.

Blodgett believes it’s wrong for public institutions funded partly by taxpayer money “to hide behind NDAs” and that the practice should be illegal. He added: “These universities are taking advantage of people who are in vulnerable situations to get around being held accountable for any past actions.”

***

Meanwhile, some Dallas College professors allege that the school pressured them to improve a grade when the student didn’t deserve it. In fall 2016, Albert Menchaca (no relation to Richard) joined as a full-time instructor and the coordinator for El Centro’s physics program. The following year, a student who consistently turned in late work disputed her grade, but Menchaca stood by his decision. It was a matter of integrity and fairness for him, and he wanted his peers to evaluate the grade change. He refused to hand out good grades for those who didn’t earn them.

Then, the student complained to the higher-ups. Menchaca said he was summoned into a dean’s office to discuss the dispute and was told to boost the grade from a C to a B. He declined.

Regardless, Menchaca said, the grade change was submitted, and he requested a copy of the form. It shows his printed name and underneath it, someone appears to have written “see email” where Menchaca’s signature was supposed to go.

Menchaca said he learned from others at the school that this wasn’t the administration’s first time overruling on a grade change absent the professor’s consent. After Menchaca contacted a lawyer, the school attached a memorandum to the student’s grade change notation acknowledging Menchaca’s disapproval. Next, Menchaca said, the administration incrementally lightened his workload and removed him as physics coordinator before he was informed in February 2020 that his contract would not be renewed.

Menchaca wants his name unattached from the grade change form. He fears the dilution of course content. At academic conferences, the talk sometimes turns to the performance of students feeding into four-year schools, he said. Menchaca has heard of some community college students who go on to major in physics or engineering at institutions like the University of Texas, just to fall flat because they weren’t fully prepared."If they can get away with doing that, they can get away with doing anything." - Jeff Blodgett, AAUP Texas Conference

tweet this

Not everyone can hold a career in STEM (science, technology, engineering and math), Menchaca said. If professors aren’t honest with students while they’re going through the process, they’ll wind up being disappointed in the end. Some students are the first in their families to attend college, or they may come from low-income households. It’s wrong to sink them into debt if they’re not being taught properly, Menchaca argued.

Blodgett, Texas’ AAUP president, believes such alleged backchannel grade-change incidents could get Dallas College in trouble with its accreditor. Anything related to the classroom, from teaching to grading, is supposed to solely fall under the faculty’s purview. Anytime a student gains a degree based on false pretenses, it works against the public’s interest, too. Changing a grade is a line where there’s no gray area, he said: “If they can get away with doing that, they can get away with doing anything.”

Citing "the importance of journalistic integrity," a Dallas College spokesperson requested "additional time to investigate the grading allegation."

The spokesperson added, "The citizens of Dallas County and the dedicated professionals working diligently to ensure that Dallas College continues to transform lives and communities through higher education deserve fair reporting that does not consist of a litany of accusations toward the end of a reporting process that offers little time to adequately respond." (The Observer requested an interview with former Chancellor May in January, which the spokesperson turned down. That same month, the Observer asked every member of the college's board for an interview; those requests were all either rejected or received no reply. Additionally, a request to interview incoming Chancellor Lonon was redirected to the spokesperson. On Tuesday, following the spokesperson's email, the spokesperson didn't return the Observer's call.)

***

Richard Menchaca had a sizable break following his first class and before the next. In years past, his schedule provided for back-to-back courses, all at El Centro in downtown Dallas, but now they were spaced further apart. Another veteran professor told the Observer that he has to be on campus by 7:15 a.m., ahead of his 8 a.m. class. Then, he waits all day to go back to work for his courses that begin at 6 p.m. and 7:30 p.m.

Sometimes during the pauses between lectures, Menchaca sticks around and answers emails. Other times, he lunches with old friends. After his second course came and went that February day, Menchaca left Cedar Valley to stop by El Centro. The schools once had unique cultures, but Menchaca fears that campus identities are eroding under the “one school” umbrella.

Regardless, Menchaca said he’s essentially being forced to retire soon because Dallas College plans to end the developmental reading and writing program. Its loss could also mean that students who already struggle with reading comprehension will have an even harder time in English class.

El Centro is home to a robust security presence. In July 2016, a mass shooting aimed at Dallas law enforcement sent shockwaves through the school. A man named Micah Xavier Johnson fatally shot four Dallas Police Department officers and one DART officer and barricaded himself inside an El Centro building. Johnson died when police deployed a bomb-carrying robot and set off an explosion that also damaged computer servers in the school.

On that February day some five-and-a-half years later, El Centro looked like a ghost town. Security and administrators appeared to outnumber students.

Around 10 people sat sprinkled in the school’s lobby, the largest gathering Menchaca recalls seeing since 2020. He misses when the hallways were still packed with energetic young adults hungry to improve their lots in life. Things are different now. “It just breaks my heart,” Menchaca said, looking up and down a deserted corridor. “It used to be bumper to bumper.” Still, Menchaca believes that Dallas College can emerge as a vibrant, bustling institution. It’ll just take a seismic shift in mindset and possibly new board members to get there.

Menchaca roamed El Centro’s halls for several minutes, thinking of the past. He saw students’ specters in the muted library and vacant classrooms. He hopes for a return to the golden age of education, but it’s unlikely that Dallas College will ever go back to how things once were.

When he’d had his fill of memories, Menchaca shuffled back outside, into the sun and onto the gray asphalt of downtown. Then, the professor hopped in the red Chevy with the eagle statue in the back and drove away.