The Case of the Headless, Handless Corpse

A reporter's tip helped detectives identify a mutilated body dumped along the Trinity, but finding the man's name led to a deeper mystery -- the disappearance of atheist gadfly Madalyn Murray O'Hair

By John MacCormack

An old man prospecting for aluminum among the junk couches, tires, and brush beside the Trinity River found the body, the one without a head or hands, on an overcast fall afternoon more than three years ago.

The nude, mutilated corpse was that of a freshly killed white man, tanned, circumcised, well manicured, and quite hairy. The corpse reposed on a rough bed of litter and poison ivy, chest up and legs together. The truncated arms flopped at rough angles to the torso, a few degrees off perpendicular. Someone, perhaps using a cleaver or heavy fishing knife, had crudely severed the head flush with the shoulders and cut off the hands unevenly at the wrists.

The body was dumped in far southeast Dallas County, just beyond Seagoville, and by the time a representative from the medical examiner's office arrived from Dallas several hours later, the flies and ants had already begun their work.

In their haste or arrogance, the killers had left the body in plain view, not far from the roadway and just yards from the river channel, something that came to both fascinate and anger the police.

"It was almost like they were daring us to discover this thing. Why didn't they dump it in the water?" asked Dallas County detective Robert Bjorklund in an interview last fall.

But if the killers were cocky, they were also fastidious.

"They took all the clothes. There was no evidence at the scene and very little blood. He was killed somewhere else," he said.

The can picker and another witness mentioned seeing two vehicles in the area along Malloy Bridge Road, one a dark Suburban, the other a white luxury car, possibly a Pontiac Gran Prix or a Chrysler New Yorker, with two men inside.

Dogs were brought in and snuffled up and down the riverbank for the missing body parts. Police in boats dragged hooks through the shallow, murky water of the East Trinity, but pulled up nothing but debris.

An autopsy performed October 3, 1995, in Dallas added little.

It noted narrowing of the coronary arteries, yellow fat on the liver, often consistent with heavy drinking, and a probable blood type of A. There were no tattoos, scars, or identifying marks on the ant-bitten body, but technicians did find a bit of blue fiber and an African-American hair.

"Based upon the autopsy findings and history as available to us, it is our opinion that this 34-46-year-old, 5'5" to 5'8" unknown light-skinned male, with no identifying marks or scars, died as the result of unknown homicidal violence," the autopsy report concluded.

The Dallas County Sheriff's Office averages a handful of homicides a year, and for the first two months, Bjorklund worked the case of the headless, handless corpse every day, searching missing-persons and crime reports for a match or a motive.

Police theorized that only a big-time drug killing could inspire such calculated savagery. Or, they joked in dark cop humor, a really bad fishing accident.

By last October, on the third anniversary of the can picker's grisly find, the case was right where it had begun. Nowhere.

"We've followed numerous leads, any leads we got. We checked NCIC missing-persons files. We exhausted that. We're at square one," Bjorklund said last fall.

That would soon change. Following a tip from a reporter, investigators identified the headless man late last month as a Florida hustler named Danny Fry, who told his family in late 1995 that he was coming to Texas to work on a big score. But coming up with a name only deepened the mystery, revealing shadowy links between Fry and another equally strange case--the disappearance of Madalyn Murray O'Hair, atheist agitator and the self-described most hated woman in America.

What was Fry's big score, and how did it relate to O'Hair's vanishing and the disappearance of more than $600,000 from the coffers of the atheist organization she founded? Lines of coincidence and conjecture bind the two cases. Trace those lines, and a murky picture of murder, theft, and scandal begins to emerge. Trouble is, the people who most likely could make that picture clearer either aren't talking or can't be found--except possibly in New Zealand.

On the Monday that the headless body appeared on a riverbank near Dallas, the plot of a celebrity whodunit was beginning to take on some complexity in San Antonio, some 275 miles to the south.

October 2, 1995--the day Fry's body was found--marked the third day since officials of American Atheists in Austin had heard from their founder and leader O'Hair, the country's best-known and perhaps most belligerent unbeliever.

O'Hair had come to prominence more than three decades earlier in the pivotal federal court battles over compulsory prayer and Bible reading in public schools. O'Hair's side won, although her role would become exaggerated over the years. But back then, in the post-war Eisenhower era, atheism ranked with Communism as ideological perfidy in the popular American mind.

To many believers, the loud-mouthed Baltimore mother was the Antichrist in a housedress. O'Hair returned like with like. She asked for no compromises and gave none in her war to hold the line between affairs of church and state.

"Religion is the most monstrous idea in the world. It must be killed without quarter along with fascism, racism, sexism, war, and slavery. All those ideas are nuts and mankind must get over them," she wrote in one of her private diaries.

Her bellicosity and love of the public eye eventually made O'Hair the face of atheism to many Americans. Over the years, she sued successfully to prevent American astronauts from praying on the moon. She also tried legally to erase "In God We Trust" from U.S. currency, but failed.

But O'Hair's gift for being offensive extended even to her philosophical allies, and in recent decades her influence in national atheist circles had diminished.

American Atheists once boasted chapters from coast to coast, but most had mutinied and broken away after tiring of the overbearing founder. By 1995, American Atheists had been reduced to a squat brick building on the east side of Austin, where O'Hair brooked no dissension.

Here, visitors were inspected through dark glass before being allowed entry. Inside, at the bookstore, the clerk gave change after carefully marking out "In God We Trust" from paper currency.

O'Hair's genius for inspiring universal resentment gave rise to a joke about how truly deserving she was of her title of odium as "America's most hated woman."

"Sure she is. All the Christians hate her, and so do most of the atheists," went the punch line.

In late August 1995, O'Hair had just returned from a vacation on the East Coast and was preparing with her son Jon Murray and daughter Robin Murray O'Hair for a trip to New York to picket the visit by Pope John Paul II. (Robin is, in fact, the daughter of Madalyn's son Bill, but was later adopted by Madalyn and raised as her daughter.)

But the plot took a sharp turn August 28 when the O'Hair family abruptly left their comfortable Austin home after taping a note to the door of American Atheists General Headquarters. Signed by Jon Murray, the note said that the paychecks would be sent to employees and that the O'Hairs would return by September 15.

The employee paychecks arrived as promised, but the O'Hairs did not return. Instead, they maintained contact by cellular phone, attending, they said, to an important but confidential business matter.

Later it was learned that they spent the month in San Antonio.

During the month, Jon and sometimes Madalyn talked to atheist officials in Austin and New Jersey dozens of times, never giving any clue that anything was amiss.

But on the afternoon of September 29, 1995, a Friday, after a final call to Jon at about 4 p.m., the cell phone went dead. There were no calls Saturday or Sunday, and Jon did not answer as before.

Monday came, and Jon had still not called as promised to deal with the representatives of the Phil Donahue show.

"Jon was supposed to call me back, specifically me, on the issue of going on the Donahue show," says Orin "Spike" Tyson, current director of American Atheists.

Phil Donahue had O'Hair as a guest on his first television show 29 years earlier. Now he was leaving the air and wanted to close out his long run in similar style.

"When they were in San Antonio, answering their cell phone, the Donahue show had been trying to get Madalyn on for their last show, and they needed an answer," Tyson recalls.

The answer didn't come Monday or Tuesday, but still atheist officials were not alarmed, even as the week passed.

"They weren't truly missing yet in our minds. I figured maybe they had said the hell with Donahue, they don't want to talk to him," Tyson says.

It wasn't until late in the week, when the three Murray O'Hairs did not appear in New York City to picket the pope, that it was clear something was amiss.

"By Thursday or Friday it began to sink in that something had gone drastically wrong with them. It wasn't yet panic, but we knew something was not right," Tyson says.

Panic eventually arrived. But for several more weeks, even when it was clear that O'Hair was gone for good, atheist officials clung to the party line that she was merely away on an extended business trip.

"The truth is, we obviously did not tell reporters what was on our minds. We tried to put a good face on it," Tyson says.

On the west coast of Florida, the friends and family of another person also missing in Texas were slipping down a parallel slope of worry and dread a few days behind the Austin atheists.

The brother, daughter, and fiancee of Danny Fry were waiting for his return from Texas, where he had gone several months earlier.

"He was going up there to work. He really didn't say much. He was just going up there to work with a friend, Dave Waters. He flew. We took him to the airport," says Lisa Fry, Danny's daughter.

"He told me it was a big deal. He would never really say if it was something bad. I'm positive it was illegal, because most of the stuff he did was. He was kind of a con artist," she says of her father.

Fry had arrived in Texas in late July, stayed at Waters' Austin apartment during August, and then moved to San Antonio during September. From San Antonio, he made occasional phone calls home from pay telephones on the northwest side of town.

While in Texas, he was close-mouthed about his work.

But his last call home had come at 2:47 p.m. on September 30, 1995, from the apartment of the man who several months earlier had induced him to come to Texas for a lucrative, if unspecified, opportunity.

The call came on Lisa's 16th birthday, but Fry was uncharacteristically tense and short-spoken on the telephone. His fiancee, who asked that her name not be published, recalls the conversation.

"He was very short with me. I said, 'Don't you want to talk to Lisa and wish her a happy birthday?' She was so psyched up for this. I remember saying to him, 'Let me put Lisa on,' and he said, 'Hurry, I've got to go.' Lisa walked away from the phone with tears in her eyes," she says.

"That last time he called, I said, 'Danny, please come home.' And he said, 'I've got one more thing to do. Then I'll come home.'"

Fry promised to be home in three days. On Tuesday.

But he never appeared or called again.

Unlike the O'Hairs' disappearance, which eventually became a national news story, Fry's remained at the level of a family tragedy. Psychics were consulted, missing-persons reports were filed in Florida and Texas, attempts were made to trace phone records, but nothing came of any of it.

Family members say they got little help from Waters when they called him repeatedly after Danny disappeared.

"I talked to this guy David many times. He ignored all my questions and said he didn't know what Danny was up to. He wouldn't give me any information," the fiancee recalls.

"Dave knew too much. To this day I think that. I wasn't there, but why would your friend come out, do business with you, stay with you, and you not have an inkling of what they were doing?" she asks.

Waters said there was nothing he could do, since he did not know where Fry had gone.

"I couldn't help her. I assured her if I had anything to alleviate her concerns, I would, but I couldn't," he says.

Perhaps, but there are inconsistencies in Waters' recollections of Fry's last days in Texas. Waters has said he lost contact with Fry at a time when phone records indicate that the pair were still in contact. Fry's family members also relate tales of veiled threats from Waters and say Waters told them he talked with Fry days after his body was dumped in Dallas County. Waters maintains his innocence, but that's a tough claim from a man with a criminal record that includes murder, a vicious assault on his own mother, and theft--including one conviction for stealing $54,000 from his former employer, the American Atheists.

A full year passed before Austin police received a missing-persons report for Madalyn Murray O'Hair. It was about that time that newspaper reporters began to sniff the air, catching the first pungent whiffs of what has become the mother of whodunits.

The report was filed by O'Hair's other son, Bill, a Washington-based religious lobbyist, who four decades earlier had been the inspiration for the seminal lawsuit over classroom prayer against the Baltimore public schools.

After a lifetime of conflict with his mother, Bill had struck the ultimate low blow by converting to fundamentalist Christianity. One of Murray's current projects is to put prayer and Bible reading back into the public schools.

"I hope she had an experience with Jesus Christ before she passed away, and maybe that is part of the reason for her mysterious disappearance," Bill Murray said on the first anniversary of his mother's absence.

"If she had the hope that by disappearing no one could pray over her remains, or she could make it clear she hadn't converted, she's done exactly the opposite. All she has done is leave room for speculation," he said.

Ultimately, Bill Murray would lose all faith in the ability or will of the Austin police to find his mother. He would conclude, as have others, that she and her two children had been kidnapped and murdered.

But none of this was apparent in late 1996.

At that time, Madalyn, who had pulled so many amazing stunts in her nearly four decades in the American public eye, was merely missing in action. Her sudden, mysterious disappearance was entirely in character.

From fleeing to Mexico to escape a charge that she assaulted 10 Baltimore policemen during a domestic brawl in the mid-'60s, to trying to heist the $300 million fortune of paralyzed porn king Larry Flynt, for whom she worked as a speechwriter in the early '80s, to the alleged attempted rip-off of the $16 million estate of right-wing California publisher James Hervey Johnson, O'Hair had proved herself capable of anything, particularly if the money was right.

Some thought the vanishing act was just a twisted publicity stunt. Her enemies were quick to pile on.

"I think what you see is the flip side of the television evangelist scheme. They've been ripping off their membership for years, pleading for money and receiving millions, and this money is essentially unaccounted for," says Roy Withers, a San Diego lawyer and O'Hair antagonist.

Withers represented the estate of Johnson, founder of Truth Seeker Magazine, which, after years of litigation, fought off O'Hair's attempt to take control of the conservative atheist organization.

"I don't think there is much romance in her disappearance. I think you'll find money and illness at the root of it. They had a contingency plan, and they executed it. This is probably Madalyn's final act, to take care of her kids. They are lost without her, figuratively and literally," Withers said in late 1996.

There was more than just good lawyerly spin to this theory.

For years, Madalyn, Jon, and Robin had run their atheist organizations in Austin as a troika, maintaining complete control over the various atheist boards and organization finances.

Rumors had long circulated of vast sums secreted in overseas accounts for the trio's eventual retirement. After their disappearance, evidence showed that the family had accumulated hundreds of thousands of dollars in New Zealand, both in their own names and in organization accounts.

It was known among inner atheist circles that the O'Hair family had examined various options for a permanent overseas retirement, with New Zealand and Australia the favored destinations.

"It doesn't surprise me at all. They made statements in the past. 'Fuck this government. Fuck this country. Fuck the IRS. We're taken care of,'" said John Vinson, an Austin lawyer, after the anniversary of the O'Hair disappearance rolled around.

"They mentioned New Zealand a number of times--also Germany and the Cayman Islands. It was not surprising. It was expected. When the government was going to come down on them, they were going to leave, and they had a lot of money stashed away," said Vinson, a former American Atheists lawyer.

"Madalyn suffers from what we call 'founder's syndrome.' She founded this organization and treated it like her own, and she thinks she deserves whatever money she wants. She can hide it for her retirement or give it to her children," he said.

At the time of her disappearance, Madalyn, 76, was in poor health, suffering from diabetes and heart problems. On top of that, there was a long-running battle with the IRS over unpaid back taxes.

Ultimately the IRS would enforce a claim for $250,000 against her.

But without proof of her fate, any theory worked as well as any other back in 1996, from aliens to abduction to foreign exile.

"My theory is, they were kidnapped and are being held prisoner somewhere in this country," says Arnold Via, a longtime O'Hair loyalist, who hosted the three at his Virginia home in August 1995. "Off the wall, I claim the Vatican did it, the Vatican or the CIA. Someone with enough clout to cover it up."

Another school suggested that Madalyn, like an ancient ailing mastodon, had slipped off into the deepest jungle for a private death and cremation.

In 1986, O'Hair had discussed her own death in an article in American Atheist magazine and outlined her fear of posthumous revenge by her religious enemies.

"I represent atheism to the world. Wouldn't the religionists love to get their filthy paws on my corpse? And so, I have told Jon and Robin, 'no funeral parlors or mortuaries,'" she wrote.

"What I don't want is for the religious to get the satisfaction of corpse mutilation or activities that would encourage them to assume that they have wrought revenge for their god...I don't want any damned Christer praying over my body or even putting his hands on it," she wrote.

But after one year, there was no proof that Madalyn was alive or dead. There was no proof of anything. But for a strange episode in San Antonio during September 1995, the disappearance of America's most famous atheist might easily have become just another surefire gag line for Conan, Jay, and Dave. Eventually, Madalyn could have joined Judge Crater, Teamster boss Jimmy Hoffa, and aviator Amelia Earhart in the book of unsolved American celebrity disappearances.

But because of one event, the O'Hair chapter is not yet ready to be written.

It began with an advertisement in the San Antonio Express-News on September 3, 1995, for a bargain-priced Mercedes. The classified ad appeared just days after the O'Hair family had left Austin for San Antonio.

It read: "88 Benz 300 SEL, $15,000 cash. Firm. 512-461-4478."

The number was for Jon Murray's cell phone, and when San Antonio real estate agent Mark Sparrow called, a man who identified himself as Jon answered.

He said the car, priced $5,000 under market, could be seen at the Warren Inn, a 300-unit complex of low-rent efficiency apartments on Fredericksburg Road in northwest San Antonio.

Jon said that he could be found at Bonnie Jean's Cocktails, a lounge in an adjacent strip center. Sparrow and his wife found Jon Murray peculiar when they came to see the car.

"His whole style was '70ish, from his acid-washed jeans to his bleached hair," Shirley Sparrow recalls.

"He looked like a barroom brawler and a heavy drinker to me. He was jittery and very arrogant," says Mark Sparrow, a former San Antonio policeman.

Despite their misgivings, the Sparrows bought the car.

Only later did they learn that their jittery Jon Murray, short and fair, did not resemble the real Jon Murray, who stood more than 6 feet tall, was dark, and spoke with a lisp.

The Sparrows believe they caught a glimpse of the real Jon Murray, and perhaps Robin as well, when they showed up to collect the Mercedes. The two were in an old pickup truck that picked up the arrogant salesman after the Mercedes was delivered.

"The one that looked like Jon Murray was driving, and the one that looked like Robin was sitting in the middle. She had to move over to let the other guy in," Sparrow says.

Since the car sale, the Sparrows have looked at numerous mug shots and photographs presented to them by reporters, but none matched.

It would be almost three years after the purchase of the car before the Sparrows saw the face of their nervous Mercedes salesman. A San Antonio Express-News reporter showed the mug shot to them last fall, and both Sparrows saw a familiar face.

"It's a very good likeness, the best yet, but I'd have to see him in person to be positive," said Mark Sparrow.

By late 1996, American Atheists officials were already weary of questions about O'Hair. Employees were discouraged from talking to the press, and President Ellen Johnson, who had replaced O'Hair as leader, ceased giving interviews.

The strategy merely fueled suspicions of a cover-up.

Late that year, the atheists inadvertently provided the first big break in the story when they filed their Form 990s, an annual disclosure required by the IRS of certain nonprofit organizations.

According to those 1995 tax statements, at least $625,000 belonging to two atheist organizations, both run by O'Hair, had disappeared at the same time as O'Hair and her two children.

"The $612,000 shown as a decrease in net assets or fund balance represents the value of the United Secularists of America's assets believed to be in the possession of Jon Murray," read the sworn 1995 tax statement.

"The whereabouts of Jon Murray and these assets have not been known since September 1995 and [are] not known to the organization at this time," read the statement.

The loss of an additional $15,500 by American Atheists, also attributed to Jon Murray, was described in a separate filing.

The admissions of huge losses contradicted repeated claims by atheist officials that all corporate assets were intact when the O'Hairs vanished.

Johnson refused to comment on the issue.

Tyson says only, "It's a very odd thing. It would appear to me they are probably not alive. Six hundred thousand dollars is a lot of reason to kill someone."

Most of the money had been withdrawn from an atheist account in New Zealand, news that further juiced the insider O'Hair bailout theory.

"Years ago, Jon and I discussed the possibility, if things got too hot and they had to skip the country, that New Zealand was the ideal place to go for the international bailout," says David Travis, an American Atheists employee.

Travis disclosed that six months before the O'Hairs had vanished, while opening the mail, he had come across a statement from a bank in New Zealand for an account containing 1.2 million New Zealand dollars.

"I don't believe for an instant there has been any foul play involved. I'm quite certain it was a voluntary disappearance. Madalyn's health was bad, and it did seem to be getting worse," he says.

But disappear where? And how?

Was it possible that these three very conspicuous people could simply vanish without a trace? Private investigators monitoring financial and telephone connections could not find a hint of activity anywhere.

As the months passed, it became harder and harder to conjure up the specter of Madalyn, Jon, and Robin serenely sipping drinks on some South Seas isle.

"You have three obese people. Robin requires two airline seats wherever she goes. My mother uses the f-word in virtually every sentence that comes out of her mouth," says Bill Murray, O'Hair's first son.

"Just singularly, they would be remembered. Together, it is just like waving a red flag in front of a bull," he says.

And where had the $625,000 gone?

The answer came in early 1998, when a collaboration between Tim Young, a private investigator, and the San Antonio Express-News bore fruit. Young, who specializes in finding people who do not want to be found, had approached the paper in late 1996 with an interesting proposal.

He offered to search for O'Hair in exchange for expense money and publicity, if he was successful. He figured that within a month or so, the job would be done.

Young proved to be an electronic alchemist at turning leaden financial, motor vehicle, and phone records into nuggets of crucial intelligence. He hit pay dirt in late 1997 when he recovered Jon Murray's cellular telephone records for September 1995.

An examination of the more than 150 calls made by Murray that month showed numerous calls to financial institutions, pharmacies, and jewelers, among them Cory Ticknor, owner of a store on Fredericksburg Road in northwest San Antonio.

The records showed numerous calls to Ellen Johnson in New Jersey and to American Atheists officials in Austin. There were also 46 calls to long-distance service connectors, a necessary step to making international calls on cell phones, like Murray's, that do not have that capability.

Analysis of the phone records led to the discovery of a crucial transaction.

While in San Antonio, Murray had bought $600,000 in gold coins--Krugerrands, Canadian Maple Leafs, and American Eagles--from Ticknor, using money wired from an atheist account in New Zealand.

Murray had taken delivery of $500,000 of those coins on September 29, 1995, but had never returned for the final $100,000 in coins, which arrived three days later.

"Mr. Murray left town when he left town, and for his own reasons. He didn't tell anyone where he was going," says Demetrio Duarte, Ticknor's lawyer. "The shipments came on a certain date, and if he didn't want to wait, that was his choice."

More than two years later, Ticknor handed the undelivered coins over to the IRS, which had opened a money-laundering investigation over the transfer of more than $600,000 from New Zealand.

The next big break in the case came in June 1998, when a tipster alerted the Express-News to the coincidental disappearance in San Antonio of Danny Fry.

"It was a kidnapping. I have the name of the person who organized it," the tipster began, referring to the O'Hair family's disappearance. "I was told by a third party who was involved, and that person has disappeared."

The man, who knew Fry, said he had seen a TV newsmagazine segment on the O'Hair disappearance and was struck by the coincidence of Fry's disappearance at the same time in San Antonio.

Crank calls about O'Hair were nothing new to reporters working the story.

Among the places she had been spotted were the Seattle airport, a monster-truck show somewhere in the Midwest, and even as a worshiper in a small Roman Catholic Mass. But this call sounded different.

As the tipster added names and details, the South Seas island family beach scenes began to make way for darker images, ones of kidnapping, robbery, and murder.

One name made this tip worth taking seriously.

According to the informant, Fry had come to Texas at the behest of David R. Waters, whose name would instantly ring a bell with any student of the O'Hair case.

Waters had worked for the Murray O'Hairs a few years earlier in Austin, first as a typesetter and later as office manager.

He quit in 1993, shortly before $54,000 turned up missing from various atheist accounts. A police investigation revealed that Waters had written himself checks for that amount.

Waters eventually turned himself in, pleaded guilty in May 1995, and received probation and orders to repay the O'Hairs. Another term of his sentence was to have no contact with the family.

Over the decades of running the atheist center in east Austin, O'Hair had become less and less selective about whom she hired to keep things afloat. Her diaries, full of complaining about money and unreliable help, reflected her derisive view of her staff.

"Rubber check time," she wrote in July 1980. "After all these years, we are back to that again. It's harder than digging potatoes to try to get money to run the center. We have no one to work in that office but scums, chicken fuckers, fags, masturbators, dumb niggers, spicks, witless cunts, derelicts, lumpen proletarian and transvestites," she wrote.

To O'Hair, Waters was just another lump, fit for typesetting.

To Waters, newly arrived in Texas, American Atheists was just a job.

"The ad in the paper was something I was qualified to do. Simple as that," he recalls.

But it is doubtful that O'Hair had ever knowingly hired a convicted murderer, and when she later found out what she had done, even the great atheist who feared neither God nor man became anxious.

"Once they found out what Waters' record was, they were definitely afraid of him. A member looked it up in the Peoria newspaper files and sent a copy of the articles where he was convicted of murder," American Atheists employee David Travis says.

"And of course Madalyn showed it to all the employees so we could all see what a bad guy David Waters was. That would have been in 1994, after Waters quit, but before he turned himself in," he says.

At age 17, while living in Illinois, Waters was charged and convicted with three other teenagers in the murder of a fourth teen, who was beaten to death with a fence post after an argument over 50 cents in gas money.

Waters and the others pleaded guilty, saying they had been drinking heavily and sniffing ether when the killing occurred in 1964. Three of the youths, including Waters, received sentences of 30 to 60 years. Waters served 12 years before he was paroled in 1976.

Waters had subsequent convictions of forgery and battery, the latter involving a 1977 assault on his mother, Betty Waters of Creve Coeur, Illinois.

According to newspaper accounts, Waters beat his mother with a broom, hit her with wall plaques, urinated in her face, and poured beer over her.

"He was walking around the room, ranting and raving, saying he wanted some whiskey, and then he was going to have a little fun with his mother," his mother, Betty Waters, testified.

But none of this was known when Waters went to work for O'Hair, rising to office manager, a position that gave him keys to both the office and, when they were out of town, the O'Hair family's five-bedroom home.

To this day, Waters denies stealing the $54,000.

Rather, he claims, he was the chump in a scheme by Jon Murray to liquidate atheist assets and siphon them away to avoid having to pay a feared judgment in the Truth Seeker suit.

"I had to plead guilty, because if it went to trial, I had too much baggage," Waters said last fall. "My lawyer told me, 'You will be tried on the facts, but you do have a past record, which will stain anything you say, and that's the reality of the situation.'"

For Waters, the time spent with American Atheists was disillusioning.

"I kind of thought it would be a hotbed of intellectual debate. But there was no debate allowed. That's for sure. It was her way or the highway," he says of O'Hair. "Madalyn to me was the most hateful individual I had ever met. I can't say that I've ever heard her say, without reservation, something good about anyone at any time."

At the time Danny Fry came to Texas in mid-summer 1995 to make some money with David Waters, he was living on the Gulf Coast with a woman he had promised to marry, raising his daughter Lisa, and, as always, looking for a fast buck.

Although family members describe Fry as a con man, they are also quick to note that he had no criminal record aside from some alcohol-related driving arrests, and no history of violent behavior.

"Danny was a scam artist, so I wouldn't put a lot of things past him," says his ex-wife, Jeannetta Camp. "He did a lot of things to make extra money scamming people, but I don't believe he would harm anyone intentionally. But people change, and I haven't been with the man for many years."

Instead, Fry made money with his gorgeous green eyes and silver tongue.

"He knew how to twist you around. He just had that way about him. I guarantee, he probably owed most people he knew a few bucks, and no one owed him. On the other hand, he would be generous when he had the money," Fry's older brother Bob says.

Fry's smooth delivery and friendly manner brought early dividends, allowing him to drop out of high school back in Illinois and make grown-up money hawking house siding.

"He started canvassing at a really young age, 15 or 16, and he did real well. He was making $300 a week back then. You know what a racket that was in the '60s and '70s. Danny DeVito did a movie about it," Bob says. "He'd open the door for the closers and keep the people comfortable while they closed the deal...Five minutes in a room with Danny, and everyone knew him."

Fry's father, Junior, worked in the local Alcoa plant. Mother Betty taught school before marrying and raising the eight Fry children, of which Danny was the fifth.

"He was the one who could always make a buck, but he'd spend it as quickly as he got it. He dressed snappy, real good, and always kept himself well groomed. He liked wearing rings and diamonds, and he normally had a nice car to drive," Bob says.

But Danny Fry was also an alcoholic, and the money didn't last.

"He always had a habit after making a big sale of taking off and blowing the money. If he had just stayed sober and used his talents, he would never have to do any of this other shit," Bob says.

Fry made plenty of money selling construction materials to victims of Hurricane Andrew in 1992, but by 1995 he was looking for the next big payoff.

Jobs selling auto lubricants and renting mopeds to Gulf Coast tourists hadn't panned out. Neither did a handyman business Fry operated out of his home in the summer of 1995. So when David Waters, an old buddy whom Fry had worked with years earlier in Florida, resurfaced, Fry was interested.

"Danny told me he didn't want to work for no $500 a week. He wanted to go for the gusto. I think he wanted big money at one time. He wasn't satisfied with a day-by-day job, and we fought about it," recalls Fry's fiancee.

"We had made plans to get married. My parents were very much against it, but I was in love. I had known him about six months, and he was a charmer. I think he was a scam artist too, because he took me for a lot of money."

Fry's fiancee paid for his ticket when he flew to Austin from Tampa in late July 1995. For a while he called home regularly from Waters' apartment in Austin.

Then, in September, the calls started coming from pay telephones in San Antonio. His last two calls home came on September 30, 1995, from Waters' Austin apartment. Then he disappeared.

While in Texas, Fry had been close-mouthed about his work, which, he said, was in the construction field and involved a big unnamed backer. But eventually the story didn't wash back home.

"At first I was concerned that he was doing well, making money. I didn't ask a lot of questions. Then I started asking questions because things didn't seem right. As time went on, he would talk less and less about what he was doing," Fry's fiancee says.

When Fry did not return to Florida in early October 1995, she feared the worst.

"I really feel this way: He got in over his head in something, and now he's at the bottom of something. I don't know who he connected with out there. It might not even have been drugs. It might have been money. It might have been anything," she said in an interview last year.

"I really thought the asshole went to Mexico to hide, to get himself out of hot water. Then I thought, all these years, his love was his daughter. Lisa was his pride and joy. He never would have left her," she said.

Fry's daughter says she doesn't know what her father might have been doing in Texas, but cannot believe it involved violent crime.

"As far as him flying to Texas to kidnap some people, that didn't happen," Lisa says. "I can't sit here and say he's never cut corners and done little things--I'm not sure what. But I lived with him since I was 2; I can't even remember him fighting with someone. He's not that type."

Questioned about Fry last summer, Waters said that his stay in Texas had been brief and that Fry had gone his own way after a couple of weeks in Austin, never to be seen again.

"He stayed here a couple of weeks. I know he was having some personal problems. I got the impression he was trying to get away from things for a while," he said in an August interview.

Waters subscribes to the theory that the O'Hairs took the money and ran.

He claims that he has internal atheist documents proving this and that he's written a book about the O'Hair case, but declined to share either with the press.

"If all the facts were laid bare, I don't think people would find it much of a mystery," he said. "I think they are kicked back somewhere, and very comfortable, and having chuckles."

Asked about Danny Fry's disappearance that same weekend from San Antonio, Waters said, "It's a hell of a coincidence, but I don't see any correlation."

There was one other coincidence that would later prove significant.

Motor vehicle records showed that Waters was also in San Antonio that month, buying a 1990 white Cadillac Eldorado with tinted windows and a blue interior from an elderly couple.

The transaction took place September 16, 1995. Waters sold the luxury car by mid-February 1996, according to records.

Waters paid $13,000 in cash for the car, just days after Jon Murray withdrew about that amount in cash from bank accounts.

O'Hair, Waters, Fry. After the anonymous tipster's call in June, the tenuous, perhaps coincidental links among these three began to become apparent. Yet the more the coincidences added up, the more the mystery deepened. Was Waters still connected to the O'Hairs after his theft conviction? Was there any verifiable link between the O'Hairs and Fry? Did Waters know more about the O'Hairs' disappearance than he was letting on? And where was Fry?

The answer to the last question would begin to come clear last October 3, when a brief item appeared on the Associated Press wire, recounting a 3-year-old unsolved murder. It began: "Detective Robert Bjorklund says it must have been a cocky killer who killed a man, decapitated him, cut off his hands, then left his body along the Trinity River in southeastern Dallas County."

At my desk at the San Antonio Express-News, I was surfing the wire and noted the coincidence of dates and victim description with the disappearance of Danny Fry. Fry had vanished September 30, 1995, and was the same race, general size, and age as the headless man.

It was a long shot, but during two years on the O'Hair story I had chased flimsier leads. After a call to Bjorklund and some veiled inquiries of Fry's relatives, the lead appeared viable.

Fry matched the estimated height and weight of the corpse. He had no tattoos or noticeable scars. Details added by friends and family members kept the lead alive.

"Some men have no hair on their back. Danny did, on the upper back and around the shoulders. He had a very hairy chest and abdomen, and very small feet, with hair on the top of his feet," says his fiancee.

Nothing yet excluded Fry from being the dismembered victim.

On October 12, I flew north to meet with Dallas detectives.

Seven of them crowded into a small interview room in the office and were handed newspaper articles published in August that outlined parallels between the O'Hair and Fry disappearances.

It was a half-hour crash course into the Byzantine world of Madalyn Murray O'Hair. A drug case probably would have been simpler to follow. The detectives read slowly and asked few questions.

Photos of the mutilated corpse were examined. A trip was made to the crime scene near Seagoville. A visit also was made to the Dallas County Medical Examiner's Office to meet the technician assigned to the case.

Bjorklund and the technician agreed to contact Fry's relatives and ask for blood to run DNA tests. The results would be compared with samples taken from the corpse before it went to a pauper's grave three years earlier.

"We have DNA on file. We have checked out three or four different people that looked like were gonna be him, but they weren't," Bjorklund said.

The actual tests take only a couple of weeks to run, but the process of securing the samples from Fry's relatives and then running the tests would consume more than three months.

Meanwhile, out of public view, other breaks were coming in the case.

Months of telephone records from 1995 showing calls Fry made to Texas from Florida and later while he was in Texas were provided to the Express-News by a Fry family member.

Crucial financial information, including Jon Murray's credit card records for September 1995, were also obtained. And efforts to track the identity of the mysterious Mercedes salesman began bearing fruit.

Finally, just before the DNA test results came in, Bob Fry, Danny's older brother, agreed to go on the record about events following the disappearance, overcoming his fears that he would suffer a similar end if he talked.

"I feel like I'd be taking a hit out on myself," said Bob Fry in late summer, brushing off pleas to go on the record.

All the new information pointed toward the same conclusion: David R. Waters knew more about Danny Fry's last days than he was telling and might also know something of the O'Hair family's disappearance.

Waters was quick to deny knowledge of either.

"I am in no way connected with their disappearance, demise, relocation to a sunny clime, or anything else that has to do with them. The last time I saw them was about a year before they decided to make this little move," he said of the O'Hairs.

He repeated assertions that his involvement with Fry in 1995 had been brief and inconsequential.

"He was ripping and running. He had his own group of friends. The last time I saw him was with a guy he was running around with. It was in Austin," Waters said last fall.

Fry's telephone records suggest otherwise.

They track an association between Fry and Waters that began in the spring of 1995 and lasted nearly until Fry's death. The correspondence began at least as early as May and intensified as spring turned to summer.

A call from Fry's home in Florida to Waters' apartment June 12 lasted 46 minutes. Another on June 22 was for 25 minutes, and on July 21, shortly before Fry flew to Texas, the records show an 87-minute call.

During August, Fry made 51 calls from Waters' apartment back to his home in Florida, and records show that his family also called him there.

Then, in late August 1995, Fry moved south. He made a last call from Austin on August 27, then two from Buda, south of Austin, on August 28, and one from San Antonio August 29, from a pay phone at the Warren Inn, where the sale of Jon Murray's Mercedes had taken place.

Fry's phone records suggest parallels to the movements of the O'Hair family, who left Austin on August 27 or 28 and resurfaced in San Antonio a few days later.

While in San Antonio, Jon Murray made numerous calls to businesses on the northwest side of town, including several within blocks of the Warren Inn.

The phone records show that the two men placed their last phone calls from San Antonio within a 26-hour span at the end of the month. On September 28, Fry made a final call home from a pay phone at the Warren Inn.

The next day, Murray made his final call to atheist officials in Austin, right before taking delivery of $500,000 in gold coins from jeweler Cory Ticknor at a bank two blocks from the Warren Inn.

Murray answered the cellular phone a couple of hours later, talked to atheist officials, and then vanished.

Fry made his last known telephone call the following day, on September 30, when he called home from Waters' Austin apartment at 2:47 p.m. during preparations for his daughter Lisa's 16th birthday party.

"He told me he'd be home the following Tuesday," Lisa says, but her dad never arrived. Two days after his last call home, a headless body was dumped near Seagoville.

New leads also refocused scrutiny on Waters' purchase of a car in San Antonio during the crucial month of September 1995.

Waters has said he used personal savings to pay for a $13,000 white Cadillac with blue interior that he bought on September 16 in Terrell Hills, a San Antonio suburb.

"I remarked at what a large stack of bills it was," says the seller, an elderly man who asked not to be named.

The purchase came, however, right after Jon Murray had used two credit cards to withdraw $10,400 in cash advances. On September 14, Murray withdrew $3,000 from a bank in Alamo Heights, another San Antonio suburb. The next day, using a different card, Murray withdrew $7,400 from a bank on San Pedro Boulevard in San Antonio.

The Cadillac purchase also came 11 days after someone impersonating Jon Murray had sold his Mercedes-Benz for $15,000 in San Antonio. Last fall, the Sparrows, who had bought the car, finally saw a face that reminded them of the jittery salesman.

"He is a very likely candidate, the best yet, but I would have to see him in person to be positive," Mark Sparrow said after viewing the mug shot of an ex-con from Illinois.

The man, who is not charged with any crime in the O'Hair case, appears to be the same age and size as the mystery salesman. During the Express-News investigation, the man's shadowy presence had been detected in several critical locations linked to the last known movements of O'Hair or Fry. (Because of the man's tenuous links to the case and the fact that he has not been charged with a crime, the Express-News has not published his name.)

Six months before the Mercedes sale, he was released from an Illinois state prison after serving more than 20 years for aggravated kidnapping. The original charges had included rape and armed robbery.

One of his fellow cons was David Waters.

In fact, according to state prison records, from October 30, 1986 until June 11, 1987, both men were inmates at the Vienna Correctional Center, a minimum-security facility where inmates are not confined to cells.

"The key here is free flow. Inmates are not limited to where they could go by physical restrictions. During free times they can recreate together, go to the dining hall together," says Nick Howe, a spokesman for the prison system.

After serving more than 20 years of a 30- to 50-year sentence, the man was paroled March 31, 1995, moved briefly to Florida, and then went to South Texas. His last known address was in Michigan.

Asked if he knew the man, Waters said, "No, not that I know of."

By this time, Bill Murray, O'Hair's other son, who knew nothing of phone records, headless bodies, or other mounting evidence, had become convinced his three family members were dead.

"I think my mother was kidnapped, Robin was taken along to take care of her, and my brother was run like a wet mule in order to get the kidnap money together. I absolutely believe that is what happened," Murray said last fall.

"Jon saw himself as the absolute worshiper and protector of his mother. I think he had his back up against the wall. I think he really thought that if he played ball with these guys and got them the money, he'd save his mother," Murray said.

Austin police maintain a different view.

"It's still an open case. Nothing indicates foul play. I feel they have left on their own accord, and they have that right to come and go as they please," says Sgt. Steve Baker, who worked the case for two years. "I believe they just took off; it was a planned departure."

On January 27, the DNA tests were released, showing a 99.99 percent probability that the headless man was Danny R. Fry. By the following Monday, Dallas County detectives were in Austin beginning their investigation.

"Our job is to get the bad guys, and that's what we're going to try to do," says Bjorklund, declining further comment.

Earlier that Wednesday, before the DNA results were known, Bob Fry had finally agreed to go public with an episode that he says took place a week after Danny had vanished in 1995.

It involved a letter that Bob Fry says Danny had sent from Texas in 1995. Bob Fry says that Waters took a very active interest in the matter when it came up in a telephone call a week after Danny's last telephone call from Texas.

"The letter said that if he wasn't back by a certain date, that meant something serious had happened. I should contact the authorities and bring in Dave Waters' name, that Dave Waters planned what we did," Fry recalls. "I called Waters and told him about the letter. I had already destroyed it, but I just told him I had an unopened letter." Things happened quickly after that.

"He said, 'Hold on to it. I'm sure he'll show up. I just talked to him the night before last from a bar in Dallas. He was drunk,'" Fry says. That conversation allegedly took place on a Thursday. Fry's body had been found the prior Monday.

According to Bob Fry, Waters and a second man were on his doorstep in Florida by the following evening, a Sunday, demanding the letter.

"They told me they were involved with something really heavy in Texas, and the people who planned it wanted them to get the letter back. And if they didn't, the people would come and get it, and they wouldn't be as nice,'" Fry says.

Fry said the two men finally left after he convinced them the letter already was destroyed. But, he said, their words lingered. (Fry said he couldn't recall the face of the second man, making it impossible to say whether it was the Illinois ex-con.)

"One thing Waters said keeps haunting me. He said, 'Your brother drinks a lot. He's got a big mouth,'" Bob Fry says.

Informed of this account, Waters says it did not occur.

"I have no idea of what you're talking about," he says.

Since he has learned that his brother is dead, Fry said his fear has been replaced by rage and nightmares.

"I'm so angry. It's different when an elderly person dies. You're prepared for those things, but when someone dies a violent death...to cut someone up like that--I'm so pissed I can barely control myself," he says.

Fry says that he suffers from post-traumatic stress syndrome from his days in Vietnam as a helicopter crew chief and door gunner and that the news of his brother's end has triggered flashbacks.

"One time while I was flying a helicopter, we were pulling out bodies, and they were hit real hard. It stunk, and everything wasn't in the bags yet. We were just trying to get out of there, and I'm kind of leaning out of the helicopter to get away from the odor," he says.

"Something rolls past my foot. I think it's a helmet. I pick it up, and it was a severed head. So now, when I pick up that head in my nightmares, it's my brother's. I've been to the hospital. I'm going to my therapist. This kind of rekindles all that shit.

"Danny was a con man, but he wasn't a violent person. He didn't deserve that. I don't like being around animals, and the guys who did that are just animals," he says.

Last week, Dallas detectives made another trip to Austin, trying to unravel the threads of a murder case that for them began with a nameless, mutilated corpse and blossomed into a full-blown celebrity mystery. Did Madalyn Murray O'Hair and her family meet a brutal end after spending a month making small talk in a San Antonio motel room with a green-eyed charmer from Florida?

And did Danny Fry himself become a victim of a violent caper that went against his character and past?

Or is David Waters telling it straight when he says that Fry just disappeared and that the atheist documents he has prove the O'Hairs took the money and ran? If so, the grand dame of unbelievers has outfoxed her religious enemies and the authorities one last time.

Although clues abound, the trail is faint. Until some more bodies turn up, cold or warm, the final chapters on Danny Fry and the O'Hair family will remain unwritten.

Postscript

Days after the story about the identification of Fry's body and his possible connection to O'Hair ran on national news wires, a woman named Larraine Capps from Bailey, North Carolina, called me in Texas.

She had read one of the O'Hair stories about the same time a petition was being circulated in her town that claimed O'Hair was alive and well and up to her old devilish tricks.

"It showed up about a week ago. The boy that gave it to me said that he got it at the Baptist Holiness Church last Sunday in Bailey," Capps said.

The petition to the Federal Communications Commission began: "Madalyn Murry [sic] O'Hair, an atheist, whose effort successfully eliminated the use of Bible reading and prayer from public schools...has now been granted a federal hearing in Washington, D.C., on the same subject...Her petition...would ultimately pave the way to stop the reading of the Gospel on the air waves of AMERICA."

The religious were urged to write the FCC in protest.

"It's just a rumor," says Mary Riddick of the FCC. "This has been going on for 25 years, and she never filed anything with the FCC. We've received hundreds of thousands of letters. They used to have boxes of them stacked to the ceiling. There was never any basis to it."

Informed that there is no such FCC petition and that O'Hair may have been dead for more than three years, the lady from North Carolina doffed her hat to the still potent atheist.

"If she can do this from the grave, she's doing damned good," Capps says.

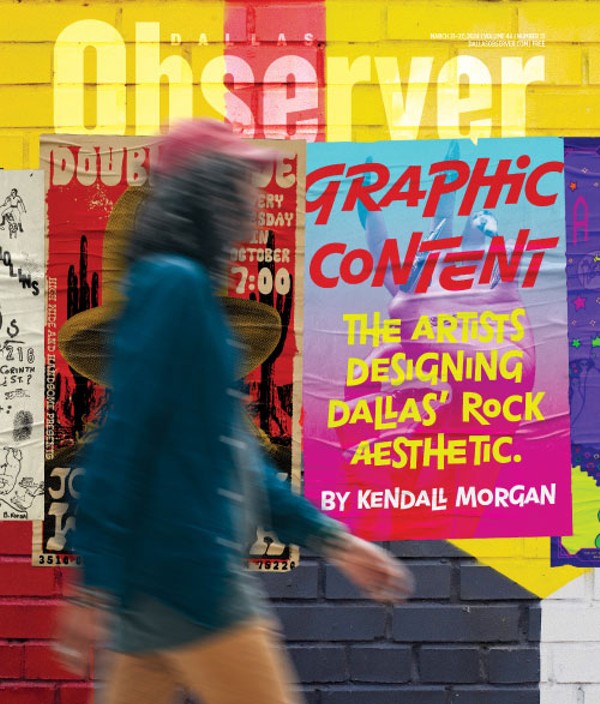

Published:A quotation in the Dallas Observer's February 18 cover story, "The case of the headless, handless corpse," concerning a claim that atheist leader John Murray had discussed fleeing to New Zealand several years ago, was incorrectly attributed to David Travis, a former American Atheists employee. The comment was actually made by Arnold Via, a longtime friend of Madalyn Murray O'Hair. We regret the error.