"We would be flying into territory that I don't think had been on television, certainly not in Dallas or America," says Ron Devillier, the KERA programming manager who made the Dallas PBS affiliate the first network to air Monty Python's Flying Circus in America in 1974. "I knew that WTTW [in Chicago] where Second City was born had turned it down. San Francisco had turned it down. Los Angeles had turned it down. Boston had turned it down. WNET in New York had turned it down, so it was risky."

Devillier's risk gave American viewers their first glimpse of future classic sketches and characters like The Fish Slapping Dance, Gumbies, the "Lumberjack Song" and the Dead Parrot, and the Pythons found a new audience of fans in America and eventually around the world.

"We just knew that something extraordinary had happened, and we were so stunned it was Dallas," says Monty Python founding comedian John Cleese. "Because in England, in the old days, we thought the people in Dallas ate their own children. We were just delighted."

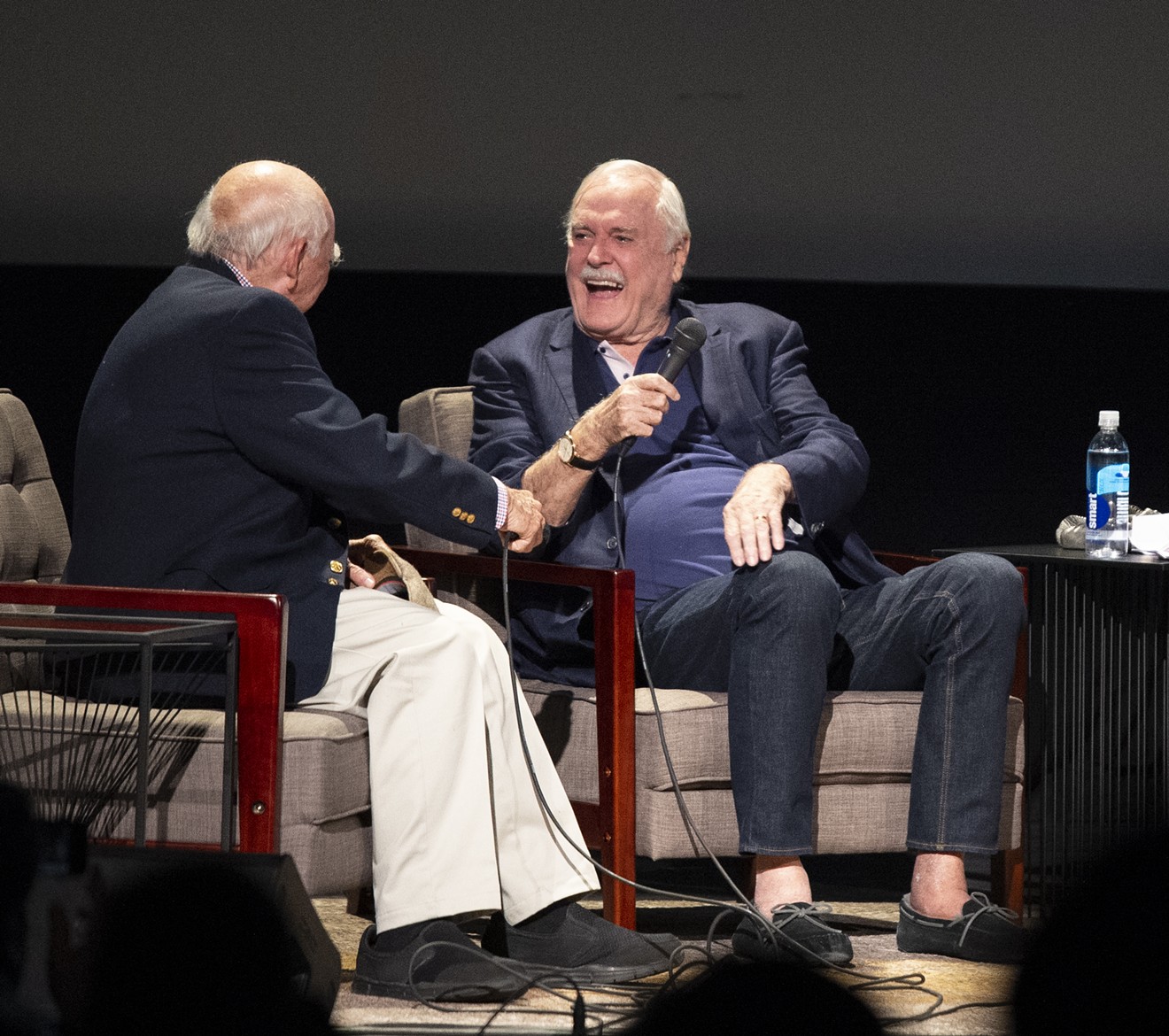

Cleese and Devillier were reunited on Tuesday and again on Wednesday at the Texas Theatre for a special presentation from the Dallas VideoFest to give Cleese the Ernie Kovacs Award, the festival's honorary award named after the famed TV comedian who found groundbreaking ways to shape and create original TV programming.

Devillier first came across the show after a national television syndicator sent him tapes of all 45 episodes of the twisted sketch TV comedy show. He went into the office on a Saturday morning to watch them and immediately wanted to put it on the air even though many other public TV stations' directors were aghast at its silly and sometimes rude manner.

"When we started Python, people really didn't understand it," Cleese says.

"Which is what made it so great," Devillier adds.

The series had a similar origin story in Great Britain, where the sketch series "passed almost unnoticed," Cleese says.

"Then at the beginning of the second series, a guy called Alan Carr, who was the editor of Punch, a defunct, funny magazine, gave us a great review in The Times [of London] and it suddenly all changed and everyone started to think it was good."

The series' original run — written by and starring Cleese, Eric Idle, Terry Jones, Michael Palin, Graham Chapman and Terry Gilliam — featured characters and settings that bathed in silliness and absurdity coupled with twisted, stop-motion animations made by Gilliam using cut-out images.

Cleese went into television comedy in the mid 1960s after he and Chapman were discovered at Cambridge University in a critically successful run of the college's famed Footlights Dramatic Club's annual revue, which also produced comedy and acting legends such as Peter Cook, Stephen Fry, Hugh Laurie, Douglas Adams and Emma Thompson. Cleese and the other Pythons worked as writers and performers on various shows until all six starting working on the comedy series Do Not Adjust Your Set starting in 1967 before creating and airing the first Flying Circus episode in 1969, according to the official Pythonline website.

Cleese says the only qualifier and motive for getting sketches on the show was he and his fellow Pythons thought it was funny."In England, in the old days, we thought the people in Dallas ate their own children. We were just delighted." — John Cleese

tweet this

"We were quite pure in our motives," Cleese says. "We worked for the BBC. We knew we would never make much money. I used to get £240 a show. For a series, I got £4,000 including the writing. We weren't doing it for the money. We did it just because we loved to make each other laugh."

Shortly after the group's debut television run, the Pythons brought their surreal comedy brand to the big screen in 1975 with the medieval epic farce Monty Python & the Holy Grail, just after Devillier put the Flying Circus show on the Dallas airwaves and its popularity started to spread as other stations added it to their schedules. Cleese says the show and the movie gave them a huge American audience and, of course, it has become one of the most memorable and over-quoted TV and film comedies of all time.

"That's why we did so well with Holy Grail because when that opened in New York, we were lucky because [the show's American premiere] proceeded it and then suddenly thanks to Dallas, people began to hear about us and then it started going out into the stations all over American, and when we opened the Holy Grail, it had this tremendous response."

The Pythons' second film Life of Brian, released in 1979, also got a lot of free publicity but the response wasn't as friendly. The film was funded by Beatles guitarist George Harrison, who put up the $3 million needed to make it because Cleese says Harrison said, "I want to see the movie." Life of Brian parodies the life of Jesus Christ through an ordinary man named Brian living in biblical times who is accidentally anointed as the Messiah while seeking ways to rebel against occupying Roman forces.

"We were sitting in London waiting to fly out to do the publicity and then somebody rang us up and they said, 'You don't need to come,'" Cleese says. "'The protesters have done the job for you.' The protests started before we even opened. They were outside and I remember seeing 'Monty Python is the agent of the Devil' and I remember thinking, 'I wouldn't mind getting 10 percent of what he's making.'"

Of course, Life of Brian also became a classic part of Python and comedy's canon, contributing more memorable moments like the ending, where Brian and his fellow crucified prisoners sing Idle's happy tune Always Look on the Bright Side of the Life, and quotable lines like Palin as a speech-impediment speaking Pontius Pilate uttering "Welease Woger!" and Cleese's Roman rebeller Arthur asking "What have the Romans ever done for us?" the latter of which Devillier says is his favorite Python line.

"I had a tiny accident with a golf cart in a Caribbean resort and the guy got out and said, 'Tis but a scratch,'" Cleese says. "I'm very touched that these words have passed into the English language."

Cleese says Python's comedy has reached to fans in places he never thought possible for a tiny show on the BBC.

"I was in Sarajevo and for four years, the Serbians were shooting civilians and lobbing bombs and they got an underground garage and set up an old fashioned theater and were showing Python movies," Cleese says. "They said, 'We came out feeling better.' We don't know why but we felt better.

"Someone said to me, 'What I love about Python is after I've watched it, I cannot watch the news' and that I think is terribly important."