For all the wrong reasons, legendary zombie blues howler Screamin’ Jay Hawkins hated my guts.

Our relationship was pretty much doomed from the start. I just couldn’t do anything right in his eyes. He and I shared the same birthday, but our commonalities ended right there. The man just lived a very difficult and complicated life. It was up to the rest of us to sort it all out.

The following experience was a bizarre exercise in diplomacy. Over the course of a year and a half, I learned a number of valuable lessons about show business and artist relations, corporate culture and inter-office politics, and the generation gap that existed at the time between punk rockers and old school roadhouse touring acts.

This was my inadvertent rite of passage into Show Business.

In the fall of 1985, Russell Hobbs opened the original Prophet Bar at the corner of Crowdus and Commerce Street in Deep Ellum. As the talent buyer for the club, he wanted me to steer the booking philosophy for the Prophet in a more “mature” direction than that of Theatre Gallery, which was our other more subversive DIY venue across the street. While Hobbs rarely ever asked me to bring in any specific artists, one of the few acts that that he really wanted to bring in was Screamin’ Jay Hawkins.

This was his mission. This was the performer who was going to put The Prophet Bar on the map.

Now, you may or may not know who Screamin’ Jay Hawkins was. (On the other hand, you might just be one of his kids. Jay was pretty much the Wilt Chamberlain of the music biz.) At the time, I wasn’t particularly familiar with his body of work, and I had no idea what we were getting into. Anna Mosca, a beautiful Italian model who was Russell’s girlfriend at the time, introduced him to Hawkins’ music while on a trip to Paris.

“Anna took me to see a Jim Jarmusch film while we were there, and that’s where I heard 'I Put A Spell On You,'” Hobbs remembers. “I got back to Dallas and thought, ‘Man, this is the perfect guy to get to come and play at The Prophet Bar.'”

It was on me to flag down Screamin’ Jay Hawkins, book him, and help to promote the show.

One phone call and I knew we were in over our heads. This guy was straight bozo. He had no manager or booking agent to speak of; he handled all of the advance arrangements himself. The contract that he sent us wasn’t a binding legal document, but what appeared to be a mimeographed list of sloppily typewritten hostage demands.

Putting this show together wasn’t easy. First of all, he wanted more money than we had ever paid any artist I had ever booked--and he wanted half of it up front. Most artists just show up in their van, set up their gear and start playing. Hawkins flew in for the show on our dime; Jay wasn’t pleased that he--and his personal valet--had to fly coach, but there was no way that we could afford to buy them first-class tickets. And Russ and I caught an earful from Hawkins driving back from the airport. He wasn’t exactly pleased that we had booked them a tiny room at a shady motel on the wrong end of Central Expressway.

“Don’t you know who I am?” he bellowed.

I started to say, “Well, Russell does… but I don’t,” but I kept my mouth shut. I just wanted this whole thing to go as smoothly as possible, and things were already spiraling out of control. This whole thing was Russell’s idea, so I was more than willing to let him take credit for the success or failure of the show.

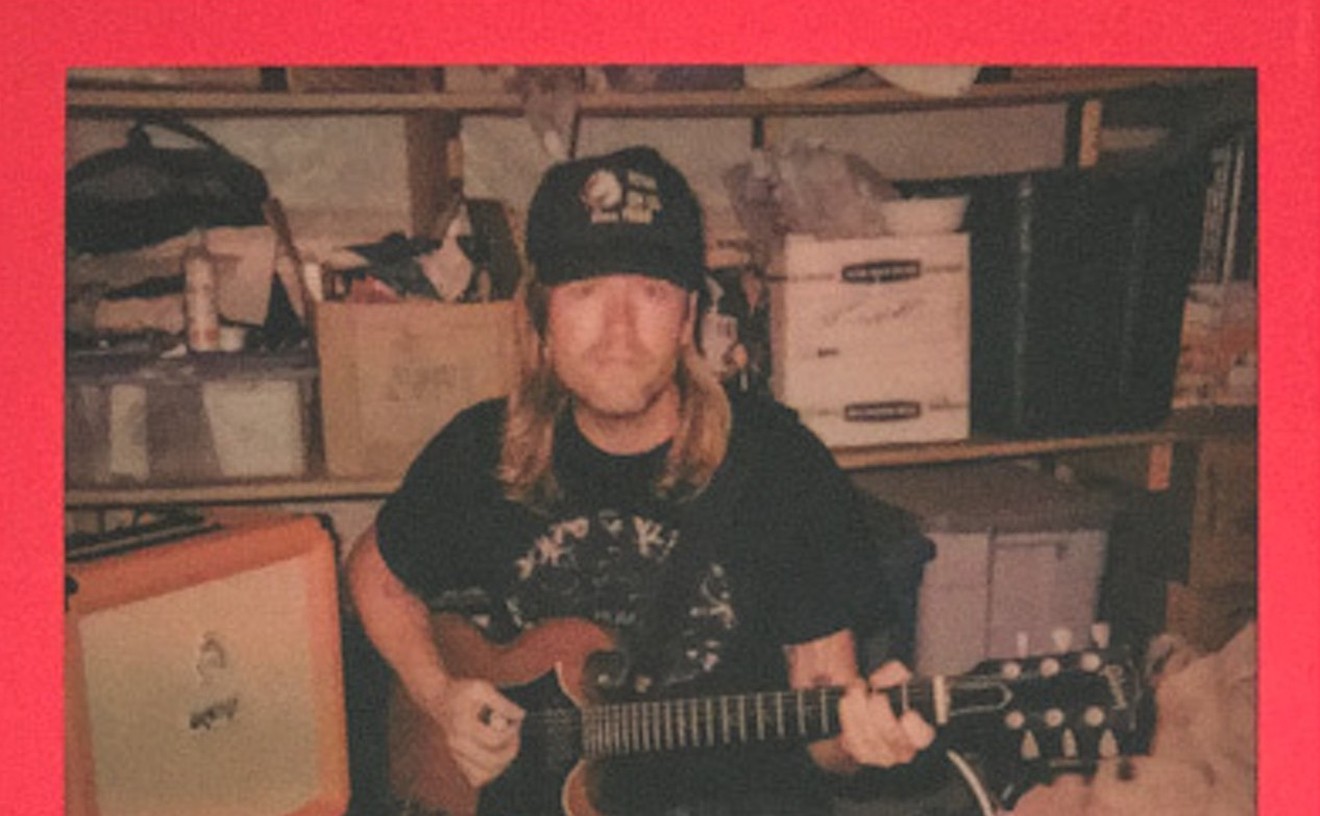

Like Chuck Berry and many other bandleaders from that era, Hawkins didn’t have a regular backing band; he used a local pick-up group in every city. Any rehearsal happened at sound check that afternoon. We had to find a group of musicians who could learn his material beforehand, which included many difficult arrangements in very odd time signatures. None of the “kid” bands in Deep Ellum would have known how to approach this performance. The only group I ever considered for the show was Reverend Horton Heat, a brand-new band led by Jim Heath, who was our soundman at Theatre Gallery. They also served as the opening act for the gig.

The show itself was amazing; probably the most memorable performance we ever had at the original Prophet Bar. Hawkins wore a black tuxedo with a blood-red dress shirt, toted a staff with a skull’s head mounted on it, and had a huge rubber snake draped around his neck. Hobbs knew that booking a show like this might conjure up the ghosts from the Prohibition-Era Deep Ellum, and he was right. The show sold out, Jay got the rest of his money, and we hustled him to DFW airport the next morning.

A year or so later, I left my gig at Theatre Gallery/Prophet Bar and took a new job as a talent buyer at the then-brand new Hard Rock Café.

Original owner Isaac Tigrett told me that he had read about what was happening in Deep Ellum in the newspaper and decided that he liked my style. I shared this new responsibility with Angus Wynne III, who booked the more traditional “Blue Monday” R’n’B acts, while I brought in the alternative acts on Tuesday nights.

This was my first “straight” gig at a corporate venue. Part of the job was taking part in a weekly meeting with a roomful of Suits--uniformed general managers and service industry consultants who hated the idea of the restaurant having to transition to a live music venue two nights a week. The room had no proper stage, which meant that we had to strike an entire section of tables and then close the restaurant for two hours in the afternoon for sound check.

At each of the weekly meetings, Isaac used to open the proceedings by asking me to roll him a joint, which only he and I would ever smoke. It didn’t help that I would often show up to the meetings barefooted and would never take notes. The Suits thought I was way in over my head and could never take me seriously.

Meanwhile, back in Deep Ellum, Russell Hobbs was determined to have Screamin’ Jay Hawkins return to the Prophet Bar again. Determined to book the show himself, he picked up the phone and called Jay at home. It wasn’t easy keeping him focused at the task at hand.

“Every time I talked to him, he would say something like, ‘I’m sittin’ here having breakfast with Little Richard. You should bring him down there to the Prophet Bar,’” Hobbs recalls. “This was at a time when Little Richard was on the skids. He couldn’t find work anywhere. I kept telling him that Little Richard was cool and all that, but I just wanted him.”

Russell finally worked out a deal to bring Hawkins back, and then sent him a deposit for a big New Year’s Eve show. Hobbs started making posters for the show and bought advertising in local newspapers.

Hawkins cashed the check for the deposit money and then never showed up for the gig.

I wasn’t on speaking terms with Hobbs at the time, so I had no idea that this had ever happened. A few months later, I called Hawkins and booked him to play at the Hard Rock Cafe. Since the whole live music thing was a loss leader for HRC in the first place, money was really no issue. The Suits cut a corporate check for half of his $5,000 guarantee, sent him a first class plane ticket, and booked a suite for him at the Stoneleigh Hotel.

Hawkins was excited about doing the show, but maintained one stipulation: “I don’t want that Horton Heat guy backing me up. He was very disrespectful--he tried to upstage me when I played there last time.”

I never even considered another backing band. Horton and his group absolutely tore it up at the previous show, whether Hawkins liked it or not. I booked them for the show and crossed my fingers; if Hawkins couldn’t deal with it, tough shit. We were paying him an ass load of money and he could just deal with it. That afternoon, a driver for the Hard Rock picked Hawkins up at the airport and deposited him at the hotel. For whatever reason, he decided he didn’t want to sound check, which I took as a blessing--I didn’t want him to see Horton and then back out of the show at the last minute.

So we opened the doors and sold the place out in less than an hour. The place was electric with an air of anticipation. Horton and his band climbed onto the stage and started doing their thing. Then, less than five minutes after I smoked a huge joint in the back parking lot with Tigrett, one of the Suit GMs came running up to me with a look of sheer terror on his face.

“Where the fuck is this guy?” he shouted. “There are two cops at the front door with a warrant for his arrest!”

Oh fuck. This wasn’t good.

I made a beeline for the Cheese Club, our VIP area that doubled as a Green Room on show nights. Surely, Jay was up there.

No dice.

I headed to the front door to see what was up with the cops. They wouldn’t tell me why they were there; they just wanted to speak with him, and that was all they would say. Freshly buzzed and without a ready alibi, I offered that maybe he was still in his room around the corner. Reluctantly, I climbed into the back of the squad car and we headed over to the Stoneleigh Hotel.

As we took the elevator up to Hawkins’ suite, I glanced over and saw some sort of summons. Clearly, this was not an arrest warrant. Turns out these guys were Sherriff’s Constables, not Dallas police patrol officers.

We made our way down the hall and I prepared to shuttle the diplomacy. As Jay opened the door, the officers got their first look at the man; dressed in a black cape, skeleton make-up on his face and a giant bone through his nose. He looked at me and said, “Why are you bringing these policemen to my door?”

They handed him the paperwork, which, as it turned out, was a summons related to a lawsuit that Hobbs was filing against Jay for not showing up to the New Year’s show at Prophet Bar.

“Mr. Hawkins, you’ve been served,” said one of the constables.

I looked at Jay and begged for some measure of forgiveness: “I’m sorry, Jay. I know you probably hate my guts right now, but there are 500 people over at the Hard Rock Café right now who are all stomping on the floor, waiting for you to come do your thing. You’re not going to jail or anything. Just come do this show and I’ll try and help you deal with whatever this is later.”

Of course, I had no idea how I was going to do that. I just didn’t want the HRC Suits to tear me a new asshole in front of Isaac and everybody else.

Five minutes later, we caught a ride in the back of the squad car over to the Hard Rock, where Jay then saw Reverend Horton Heat tearing the roof off the place as his opening act and back-up band for the evening.

The deputies hung around and caught most of the performance. Hawkins stepped up and arguably put on the best show that ever happened at the Hard Rock (although the Hard Rock might be reappearing in town soon enough); even the Suits were smiling as he brought down the house.

By the end of the show, I high-tailed it the fuck out of there and left a real professional like Angus to settle the pay out.

I didn’t last too long in the uptight corporate culture of Hard Rock Café. Tigrett and Wynne were my only co-workers who appreciated live music. Not long after that I returned to Deep Ellum, this time as the booking agent at a new club called Trees. Russell Hobbs never did get his deposit money back from Jay; and Hawkins died of a brain tumor in 2000, ironically enough, on the exact same day that former Dallas Cowboy head coach Tom Landry passed away. --Jeff Liles

The Reverend Horton Heat performs Saturday, October 18, at Main Street Live.