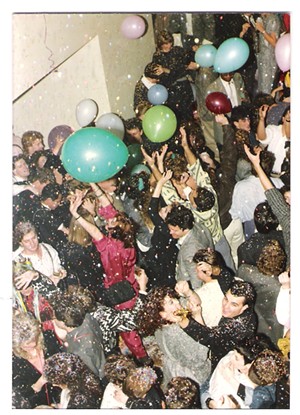

Opened in May 1984 and closed in July 1989, the Starck Club has gone down in local lore as a glimmering temple of excess. With its black terrazzo finish and floor-to-ceiling curtains, the club played host to an exquisitely outrageous masquerade. Night after night, the best and brightest of Dallas nightlife lined up for a chance to see, be seen and rub elbows with everyone from Prince to Princess Stephanie of Monaco.

“It was a live fast, die young and leave a beautiful legacy type thing. It was one of the most influential clubs in the country,” says Don Nedler, who has owned Dallas’ Lizard Lounge for more than 25 years and briefly revived the Starck Club name in the mid-1990s. “In my mind, it had a pretty short run for a club as innovative as it was, as far ahead of its time as it was and of such tremendous quality. Quality is an important word because everything they did was so over the top.”

“It was a live fast, die young and leave a beautiful legacy type thing. It was one of the most influential clubs in the country." – Don Nedler

tweet this

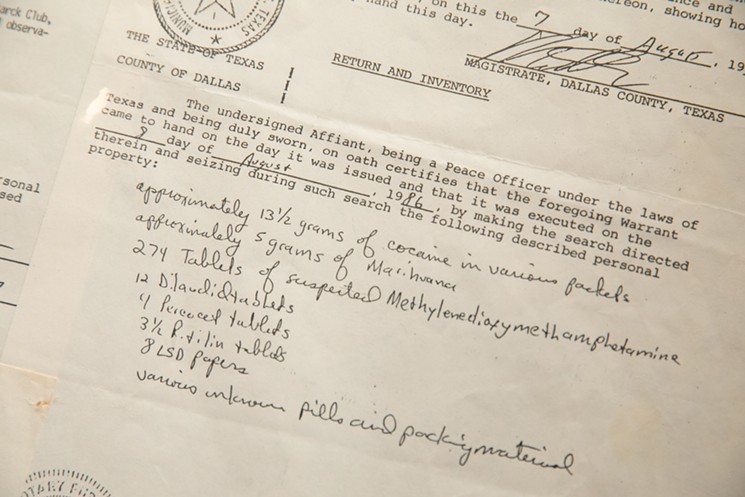

Among the Starck Club’s infamous indulgences was MDMA, which was legal at the time of its opening. Better known as ecstasy, MDMA’s subsequent banning would help hasten the Starck’s downfall, as its perceived role in the proliferation of the drug landed it on ABC Nightly News. A raid by the Drug Enforcement Agency in August 1986 ultimately ended what many felt to be the club’s golden age and forever colored its reputation.

But beneath the glitz and glam that have come to define the Starck’s legacy, those who worked at and frequented the club remember it having a deeper and longer-lasting impact on Dallas’ cultural landscape. A handful of local artists were given free rein to use the space as a blank canvas for everything from fashion shows to video installations to nurturing the city’s then-nebulous dance music and rave scenes. It even helped foster the crossover of the city’s gay and straight club cultures.

“The beauty of Starck was that everyone was there,” says George Baum, who worked as a doorman at the club and sometimes DJed at its basement bar, called Cold Bar, on Sunday nights. “The hairstylists were really the scene makers back then. They were there, everybody had good hair and everybody looked good. It was really a time of intense creativity in the city.”

To people like Lone Star 92.5 FM on-air personality Jeff Kovarsky, the true significance of the Starck Club, especially resident DJs Rick Squillante and Mike DuPriest, is underappreciated. Kovarsky credits DuPriest with being at the forefront of bringing house and acid house music to Dallas and helping to launch Kovarsky’s own career in radio.

“When I walked through those drapes, it changed my life,” Kovarsky says of his first visit to the Starck Club. “People look at Dallas as cowboy boots and hats. You mean to tell me that one of the most cutting-edge underground cultures in America had its hub in Dallas in the late ’80s? The answer is yes.

Most Exciting Thing in the World

From the outset, the Starck Club was as much an overgrown art project as it was a nightclub in any conventional sense. No expense was spared in its immaculate, high-end presentation, from its custom-built furniture to its crystal glassware and designer uniforms worn by the waitstaff. Even the ice cubes were measured to exacting standards. Over budget and behind schedule, the club developed a reputation long before its doors opened.“There was a year or two of speculation on when it was going to open. All of us had heard about it,” says Nick Hamblen, who owned a vintage clothing store at the time called Flaunt and went on to work at Starck Club himself, first as a doorman and later as operations manager. “We searched the paper for any information (we could find). It was the most exciting thing in the world.”

A sense of elusiveness was sewn into the fabric of the club. Founder Blake Woodall, born into his family’s Vent-A-Hood fortune, got the idea from a visit to the Spanish resort island Ibiza in the early 1980s. “I just wanted to own the most remarkable nightclub in the world,” he says wistfully. But Woodall didn’t want it to be easy to find. That’s why he chose the Brewery Building, with its entrance in the back of the building and no outside sign for the club. “I loved the idea of having to find something. It was an intellectual experience. People love finding something. They want to be in the know,” he says.

People were left in the dark about the Starck’s investor group, as well, all of whom were required to be 35 or younger and contribute $50,000 of capital. (“Trust-fund babies,” as Woodall puts it.) One of those investors was Christina de Limur. “The point of the whole thing was to bring a little Paris to Texas. Bring something exotic, something different. It was a gamble, but it was a gamble worth taking,” she says. Raised in Paris herself, de Limur had relocated to Dallas from San Francisco a few years earlier. “We were at the right place at the right time. Dallas was like a boomtown then.”

The Starck Club might as well have come from another planet. “To me, that was Dallas’ first step toward truly being an international city,” says Greg McCone, the club’s general manager throughout its existence. “If you went back 12 to 13 years, you couldn’t even buy a drink at a bar in Texas. So we were coming out of the 18th century, practically, compared to anyplace else in the country.”

“Almost no one was coming, yet they were turning people away.” – Nick Hamblen

tweet this

Often compared to such heavyweight clubs as New York City’s Studio 54 or Manchester, England’s, The Haçienda, the Starck Club made a unique architectural statement. Lavish and austere at the same time, it was the work of a then-unknown French designer named Philippe Starck, who was whisked away by French President François Mitterand to remodel Élysée Palace midway through the club’s construction. There were no disco balls in the building, and the only artwork was painted on concrete pillars by Dallas artist Dan Rizzie. Most notable was Starck’s decision to place a sunken dance floor in the middle of the room and have a DJ booth that faced away from the front door.

“It was so ahead of its time. Philippe Starck put form before function. He didn’t care how it worked, he cared how it looked. Some of the design was very frivolous,” says Nedler, singling out the practical difficulties of the dance floor. “Some people say it was innovative, but from a nightclub operator’s perspective it was a nightmare. You could have 600 people in the club when you walk in and have what appeared to be an empty room.”

Filling the room wasn’t easy, especially in the club’s early days. Though an opening night party featuring performances by Grace Jones and Stevie Nicks, who was one of the Starck Club’s investors, brought a packed house, its exclusivity (beyond the price) was something of an illusion, conjured by the strict and seemingly capricious admittance policy of doorwoman Edwige Belmore. “Almost no one was coming, yet they were turning people away,” Hamblen says. “Of course, that made tons of news, and the reputation never left the club.”

At its peak, McCone estimates that the Starck Club drew between 3,500 and 4,000 people on a Friday night, virtually all of them dressed for one of the many themed parties. “The guy standing next to you is buck naked in a terrycloth bathrobe, and the guy on the other side of you is dressed as a girl in green makeup. It’s Halloween every night,” he says. That person could just as easily have been Rob Lowe, a member of New Order or the cast of Dallas, or even a young George W. Bush, who attended one of the GOP fundraisers that catered to the club’s conservative benefactors. Woodall says the club’s allure for the was enhanced by a no-camera policy. “Celebrities need a place they can go and just be themselves, not have people filming them,” he says.

Key to those parties was a decision to join an injunction started by two local gay bars that allowed the Starck Club to stay open all night, which wasn’t allowed under Dallas ordinances. “At 8 o’clock on a Monday morning, I’d open the doors, and 300 to 400 people would pour outside. Everybody’d be on the overpass above ’em, bumper to bumper, going to work downtown,” McCone says. “I’d be the last one out, walk over to the magazine rack, read The Dallas Morning News and read about the party I was walking out of.”

A list of all the illicit drugs confiscated at the club on one August night in 1986 included about 13.5 grams of cocaine.

courtesy Greg McCone

X Marks the Spot

The Starck Club was a fixture in the local news, but before long it was landing there for the wrong reasons. Ecstasy first entered the club on opening night thanks to DJ Kerry Jaggers, who flew in from New York with a shipment of it. “That was the first anybody had even heard about it. Two months later it started becoming a thing, and Channel 8, Channel 5 News are coming down to the club wanting an interview,” McCone says.Soon the Starck Club was being blamed for starting an epidemic. While the drug was a crucial ingredient in the club’s party cocktail, it was hardly exclusive to Starck. “Everybody was taking ecstasy back then,” says Jeff Liles, who helped open Theatre Gallery, the first modern-day venue in Deep Ellum, in 1985. “One thing we did have in common with both venues was that they benefited from the fact that ecstasy was legal, because the effect of that drug was that you’d love everybody. That’s how we ended up getting along.”

The clubs that began popping up in the wake of Starck’s popularity were typically worse about their ecstasy consumption, says Wade Hampton, who DJs under the name WishFM. “There were places where it was all over the bar, but I wouldn’t say Starck was one of them. (Elsewhere) it was far more lawless, to where people were literally walking around with handfuls of it giving it away,” he says. Hampton went on to run several of his own clubs and now serves as the Coachella broadcast assistant producer and music supervisor. “If it had just become a free-for-all, I think the mystery would have gone much sooner.”

Lost in the headlines and celebrity sightings was a creative program that broke new ground in Dallas. Besides the array of costume parties with everything from Christmas to Egyptian themes, Starck hosted regular fashion shows run by Kayce Geer. She’d previously organized punk rock fashion shows under the auspices of her Plastic Opera Co. ensemble at gay and underground bars, where she wouldn’t have dreamed of the resources or exposure offered at Starck.

"It was a chance for Dallas to be world class. It worked out beautifully. It definitely put us on the map.” – Frank Campagna

tweet this

“I absolutely never would have had that type of platform (otherwise). I couldn’t believe they just let me have a free run of everything there. They just asked me not to scratch the floors,” Geer says with a laugh. One of her favorite events was a Bauhaus-themed wedding complete with dry ice on the dance floor, stuntmen scaling the walls and a release of doves at the end. “I used a lot of local designers who were just starting out. It was really fun to have some fashion that was new and innovative that I didn’t have to try and find at a store, off the rack.”

Like the crowds who came there to party, the performers in Geer’s shows were as likely to be gay as they were straight, and often dressed in drag. Though Dallas already had a thriving gay club scene, it was a watershed development for a mainstream club in the city. “That had never happened before. There’d never been a mix of straight and gay crowds in a dance club, and it was just open season,” Hamblen says. “I think it was really super attractive for both sides. I’m a gay man, and it was nice to go to a bar that was so incredibly mixed. (The Starck Club) opened the door and we never turned back.”

Equally progressive was the club’s nongendered bathrooms, a concept that took another three decades to gain widespread use with local businesses. “I wanted stalls you could go into, lock the doors and take care of all the business you might want to take care of in a nightclub bathroom, as opposed to just the utilitarian aspect,” Woodall says, mischievously. Those stalls were equipped with overhead TV screens that played experimental art videos produced by an in-house video team, which included David Hynds, Suzy Riddle and Mark Ridlen. Another larger screen was in the lobby.

“Basically, I had a full-time job being a video artist, which very few people have,” says Hynds, who points out that VHS was then a new and relatively expensive format. The Starck Club became an early sponsor of the Dallas VideoFest, and Hynds was responsible for the visuals that projected onto the club’s curtains. “It took 20 minutes to switch out all the slides and completely change the nature of the room,” Hynds says.

The Starck Club also booked live music, with artists like RuPaul, Red Hot Chili Peppers and Kid Creole and the Coconuts playing upstairs on the dance floor and other, often local acts performing in the Cold Bar. Liles’ band Decadent Dub Team played the club more than once, while Ridlen’s longtime band Lithium Christmas started as a house band for a Stark Club Christmas party. “One of the more surreal things I saw there was when they hired the Nelson Riddle Orchestra for Valentine’s Day,” Ridlen recalls. “This guy was a world-famous bandleader, and you could tell — he was just like, ‘When’s this over? Where’s my check?’”

Whether that programming helped open doors to local artists outside the Starck Club circle is harder to determine. “It was an isolated thing,” reckons Frank Campagna, who had opened his Studio D event space in Deep Ellum in 1982 and got a job as a bar back to get in free on Starck’s opening night. “(But) it was a chance for Dallas to be world class. It worked out beautifully. It definitely put us on the map.”

At a reunion party at Beauty Bar, Kerry Jaggers, a former DJ, signs Craig Depoi's art piece.

Nathan Hunsinger

Rave On

Perhaps no two figures loom larger in the story of the Starck Club than its two longest-running resident DJs, Rick Squillante and Mike DuPriest. Who exactly was the more influential depends on who’s being asked, but between them, their musical selections helped define the club’s two eras, before the DEA bust and afterward.Neither one was the original man for the job. That honor went to Frenchman Philippe Krootchey, who actually missed opening night because of a scheduling conflict stemming from the club’s construction delays. (Kerry Jaggers was his replacement.)

“(Krootchey) would play something three times in a row and kind of sloppily scratch, throw people off in their rhythm while they were dancing. People would boo, and I thought, ‘That’s great!’” Ridlen says. “He was kind of a punk-rock DJ, in a way.”

Ridlen himself was one of the club’s DJs, and Hampton says his contributions have often been overlooked. “Mark helped set up these raucous, anything-goes, highly contrasting sets where he was drawing on all types of genres,” says Hampton, who was still underage when he first sneaked into the club. “He had more of this punchy flavor that was probably more suited for the bombastic desires of a Dallas crowd” than Krootchey.

"There’s never been a place that had such a quote-unquote vision and had enough people on board to actually make it happen,. Everything else is just permutations of it.” – Mark Ridlen

tweet this

Building on those foundations was Squillante, who came to Dallas from San Antonio on the recommendation of Jaggers. He added more new wave and obscure European dance tracks and was renowned as a tastemaker and storyteller. “Rick refused to play anything that bordered on Top 40,” says his longtime friend Karen Kennedy. “Somebody asked him to play (Aretha Franklin’s ‘Pink Cadillac’) and he said, ‘If you want to hear that record, go out to your car and turn the radio on.’”

Working as a reporter for Billboard, Squillante was able to turn several songs into charted hits, most notably Uptown Girl’s version of the Temptations’ “(I Know) I’m Losing You” — at which point he would promptly stop playing them in the club. “DJs all over the country were watching and listening to Rick Squillante,” says Nedler, who at the time worked out of Houston for the Confetti’s Night Club franchise. “He was playing music you couldn’t hear at any other local club — that you couldn’t hear at any other club in America — until he made it relevant.”

Squillante is also fondly remembered as a mentor to then-aspiring DJs like Hampton. “Oddly, in the most exclusive place in town, you could walk right in and eventually get to the DJ if you wanted to. Then you meet (Squillante) and realize he’s this bubbly, funny guy,” Hampton says. “There weren’t a lot of other DJs who would stop and give you the time of day, and yet he would. Sometimes we’d just stand there and watch what he did for hours on end.”

Squillante’s exit in 1987 opened the door for “Go-Go” DuPriest, who, like his predecessor, was gay, and whose arrival dovetailed with a new generation of clubgoers. DuPriest’s sets were more tightly focused on house and acid house music, but just as important, saw him make use of three turntables instead of two. “His desire to spread out as a DJ and get on three turntables was really a line in the sand,” Hampton says. “It was a definitive shift to what I’d say were the beginnings of the rave scene.”

Among those taking notes on DuPriest’s DJing was Scottie Canfield, who serves today as the resident DJ at It’ll Do Club under the name RedEye. “One of the major things I took from him was, even if you are playing music that other folks are playing, the way you play it is what sets you apart,” Canfield says. He agrees with Hampton that DuPriest helped lay the groundwork for the ’90s rave scene in Dallas. “This was absolutely where the ball started (rolling). That was the crew.”

Jeff Kovarsky is likely the most well-known disciple of DuPriest as far as Dallas residents are concerned. He was hosting his first radio show with KNON when he first visited the Starck Club and would go on to host 94.5 KDGE FM’s Edgeclub 94 mix show starting in 1991. “By the time he finished, he was in the middle of the dial playing hardcore drum ‘n’ bass on a Saturday night all the way into the mid-2000s, on a big Clear Channel station,” Hampton says. “That’s huge. Only one other market had that, and it was Los Angeles.”

Kovarsky, who goes by Jeff K and is now also an in-stadium host for the Dallas Cowboys and public announcer for the Dallas Stars, says it was all possible thanks to the Starck Club. “Mike DuPriest took me under his wing and taught me how to mix, so I became a big rave DJ in the ’90s,” Kovarsky says. “None of that would’ve happened had it not been for the time that Mike took to show me what beat mixing was all about.”

The Party's Over

From left: Billy Boots, George Baum, Mike Medley, Mark Ridlen, Craig Depoi and Greg McCone stand in front of the former entrance to the Starck Club.

Nathan Hunsinger

That wouldn’t quite be the last chapter in Starck’s story, as Nedler brought the name back in 1996, though only after going to court with Woodall, who had developed a drug addiction before becoming a born-again Christian. This time, Dennis Rodman was the big-name investor, while Ridlen returned as the bathroom DJ. “A lot of the original Starckers were like, ‘Oh my God, why would you do that?’ They were appalled. They thought it was like opening up a coffin,” Ridlen says. “But I had arguably as much fun then as I did in the early days.”

More disagreements would follow when a pair of rival documentaries on the club started production in 2009, one a 20-minute short and the other a feature-length film directed by Michael Cain called The Starck Project. Originally premiering at the Dallas Film Fest in 2014, it was written about in The New York Times but has never seen wider release. Hampton was the film’s producer and music supervisor.

Several of the Starck Club’s most memorable figures have been lost over the years, including Squillante, whose suicide in 2001 shocked even his closest friends, and DuPriest, who died in a car accident five years later. Their reputations have lived on, even if more so outside of Dallas. “In my travels, or when DJs travel here to play, they all want to know about Starck, what it was like, and if it was all true,” Scottie Canfield says.

Little evidence remains today of that colorful past, though the Starck Club itself has so far been spared by developers. A sign in the upper corner of the building advertises its most recent tenant, Zouk Nightclub, which closed in 2014. The red carpet lining the front steps is ripped and discolored, while a pile of twisted scrap metal and battered wood lays on the sidewalk just inside the fenced-off construction area. Even the huge, steel front doors are gone from the boarded-up door frame.

The era of the Starck Club has long since passed, as has the era of bombastic, large-scale dance clubs, and Dallas is likely never to see another one of its kind. That, as far as Ridlen is concerned, is how it ought to be. “It was the first, and they had the deep pockets to actually execute in a quality way. There’s never been a place that had such a quote-unquote vision and had enough people on board to actually make it happen,” he says. “Everything else is just permutations of it.”