But first, with the group gathered in the immense, wood-paneled kitchen, Abbruzzese lights up a cigar. The stogie has an odor not unlike that of a petting zoo. Abbruzzese narrows its scent down further: "sheep dung." His colleagues enthusiastically agree. Unfettered by this revelation, he continues to puff.

Everybody climbs into the cab of Abbruzzese's truck. As Abbruzzese starts to manhandle the big vehicle across the rugged landscape, Slavens points out the headlight of a train on the distant horizon. Somebody figures there's enough time to rendezvous with it.

Abbruzzese carefully negotiates his truck around trees and over ditches and the other obstacles encountered when you leave the roads and even trails behind. He reaches the elevated berm on which the railroad tracks run and stops the truck. He's the first to hop out of the cab, and he climbs into the truck bed, encouraging the rest of his crew to follow. He's clearly reveling in the beautiful 50-degree night and the starry sky. The other guys scramble into the back, careful not to slip on the condensation that has formed on the bed's metal surface.

"We've reached dewpoint!" Abbruzzese declares. He's obviously stoked, digging the air, the trees--the nature all around him. The thought of just being here seems enough for him.

Slavens, Neil, and Muller take in the surroundings with lesser degrees of enthusiasm. Muller, lanky and soft-spoken, silently takes in the stars. Longtime Abbruzzese pal Neil is exhausted to a droopy daze, but he still seems to enjoy the nighttime beauty. Slavens looks cold--shivering in a jacket, a knit cap over his shaved head--trying to keep warm in the moist chill despite his knee-length shorts.

"Tonight is kind of a little celebration for me," Abbruzzese announces.

"Yeah? What are you celebrating?" asks Slavens. Among the four, only he can speak in a voice that matches the commanding tone of Abbruzzese's.

Abbruzzese takes the cigar out of his mouth. "I'm finally free--from all the legal stuff with that band." A silence follows, as there usually is whenever he refers to "that band." Even Slavens remains quiet. Abbruzzese looks back up at the stars, puffing on the cigar again.

No wonder he appears to be taking in everything tonight as though it were a brand-new world. To Abbruzzese, it is. And in a new world, even a dung-smelling cigar is something to be savored.

Soon the train arrives, drowning out any attempt at meaningful conversation. Everybody turns their attention to it, if not their thoughts. There's some speculation about which direction it's headed--toward Dallas or toward Fort Worth--though it really doesn't matter. Watching the cars rumble by in the darkness, going somewhere, is satisfaction enough.

A couple of weeks earlier, inside the Kharma Cafe opposite the University of North Texas campus in Denton, Abbruzzese reflects upon his recent, famous past with Pearl Jam. It is 3 a.m., but he is wide awake.

"It's either I love every one of those guys and wish them even greater success," he says in his characteristic, amiable way, "or [that they] just die in a plane crash."

It's a joke, of course, but it illustrates the conflicted feelings Abbruzzese harbors for his former colleagues.

At 28, Abbruzzese has entered a kind of retirement--from a life that, for all intents and purposes, was in another world. It has been a little more than two years since he was fired from Pearl Jam. To this day, the former drummer of the hugely successful band says he was never given a reason why he was let go. He never expected it. It just happened.

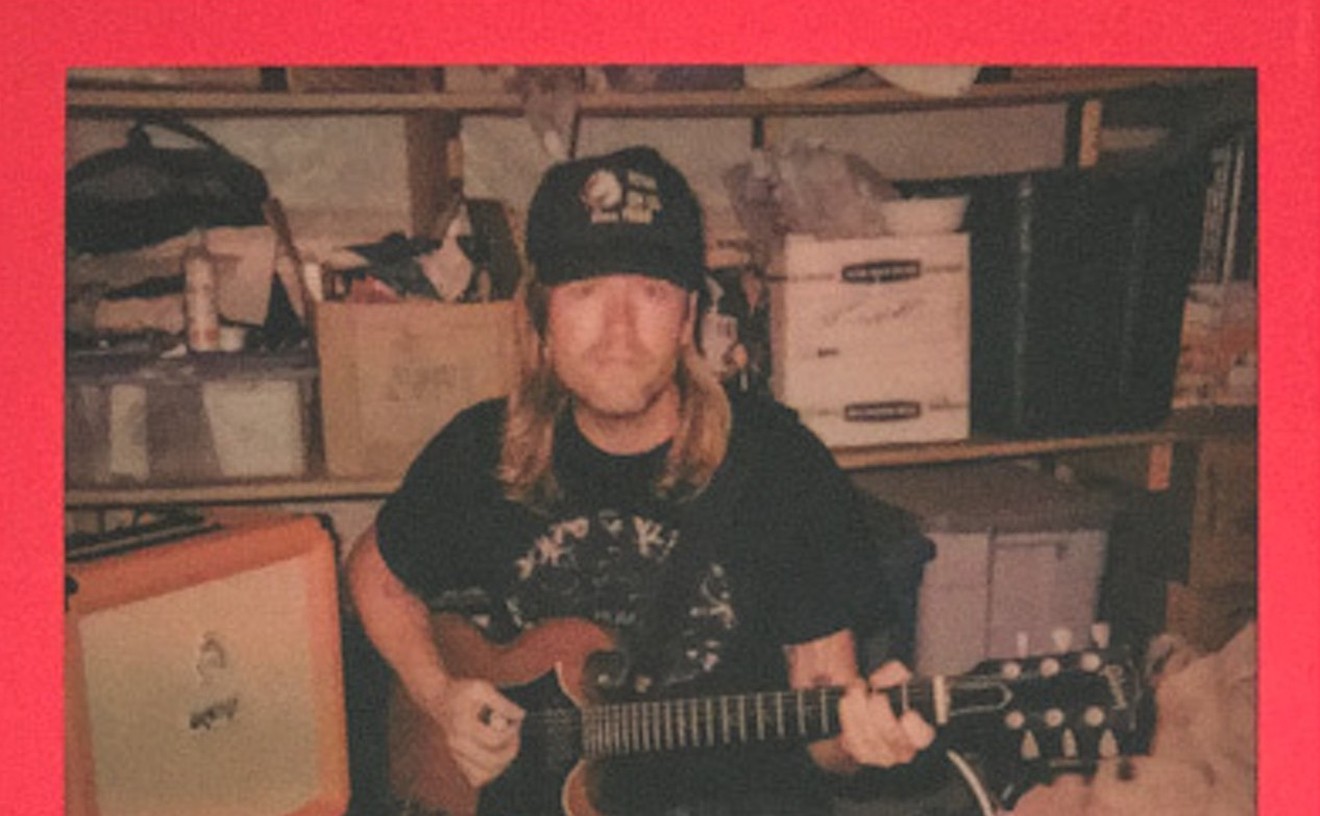

Abbruzzese, with his long hair, stocky physique, and soul patch--a smidgen of a beard beneath his lower lip--has a way of looking slightly displaced, like a musician whose bandmates accidentally left him behind after a gig. Even when he's with the members of his new band, Green Romance Orchestra, Abbruzzese seems like he belongs somewhere else. Perhaps it's the childlike enthusiasm and unrockerlike lack of pretension he exudes. Whatever it is, it made him sharply stand out from his fellow, more consciously subdued Pearl Jammers. So maybe it's true, as many Pearl Jam fans suspected, that he never fit in with them either.

Bitterness and anger are difficult to associate with this fundamentally good-natured man. But hard feelings, following his abrupt firing, would be understandable. After all, it's not like he was a temp. Though he was the band's third drummer in less than two years, Abbruzzese was also its longest employed and, most critics agree, the drummer who most significantly contributed to the evolution of Pearl Jam's music. His drumming agility has been described as hard and fast. Critics and fans remember him for pushing Pearl Jam toward an edgier, harder rock sound. Taking up where second drummer Matt Chamberlain left off, he began shaping the band's beat when he first started touring with Pearl Jam in 1991. The band's sophomore album, Vs., which followed two years later, was the first to which Abbruzzese contributed his talents.

He lived, worked, and played with the band's other members--Eddie Vedder, Stone Gossard, Jeff Ament, and Mike McCready--for four years. He also grew with them. Signing on with the band at age 23, this high-school dropout was its youngest member, compared to the others, who were in their middle to late '20s at the time.

Today, Abbruzzese sounds exhausted about the whole affair. It's not that his stint with Pearl Jam--ranging from the band's modest early days to the height of its success--wasn't a wonderful experience, he says. It was. It's just that, since then, he has become wary of still being associated with them.

It doesn't appear to bother him when any of his new music collaborators rib him about being a "rock star." He takes it about the same as when people perpetually mispronounce his last name. (For the record, it's pronounced "A-broo-zees.")

But when gently pressed about his time with Pearl Jam, he says little and never calls the band by its name. It's always just "that band."

His childhood growing up in Mesquite was pretty normal, Abbruzzese confesses. "Total middle-class family. Good upbringing. Wouldn't change a thing."

Born in Connecticut, his family ("older brother, younger brother, mom and dad--still together") eventually made their way to Dallas in 1976. His father worked for the now-long-gone Treasure City department store in Oak Cliff.

"I was a way-shy kid. Really quiet," he says. "I remember looking at the world and thinking it was an odd and funny place.

"Then we moved to Texas," he says. "Then I found out my hair was too long for being in Texas. Texas was a really bizarre place to come to when I was 8 years old."

As a teenager, he never thought much about his future.

"I did a lot of silly things," Abbruzzese says. "Things that just about everybody I knew was doing at that time. If we didn't smoke a joint on the way to school, it was going to be a bad day. It was classic--mid-'80s kind of days. It was a good time but a confused-teenager time. The only thing I wasn't confused about was how I felt when I played music."

He dropped out of high school during his freshman year. "I decided that school was completely uninspiring to me. And not just because of the drugs," he says. "I attribute my experimenting with drugs to the way education was handled in the '80s. Hair code--had to have your hair a certain way. Dress code--there was no way to express yourself in Mesquite, Texas, in the '80s. Pretty much the only way you could be creative is if you were a troublemaker."

Music had always been a part of Abbruzzese's life, as far back as when he was 4 years old, when he first took up drumming. He has never taken any lessons, and no one else in his family was musically inclined. The talent just came to him--with AC/DC, Pink Floyd, Led Zeppelin, and Peter Gabriel providing the inspiration.

"So I was an insecure, transplanted Yankee living in Texas, playing the drums, because when I had headphones on and my eyes closed and was beating the hell out of my drums, it was my only release," he says. "It was the only thing I was really comfortable with."

After dropping out of high school, figuring that he "would worry about things when I turned 25," Abbruzzese spent seven years playing in various bands in the local music scene. He drummed for the funk act Dr. Tongue (in which he played along with Neil), Segueway (an "instrumental freak-out"), the Flaming Hemorrhoids and, for a few months, Course of Empire. Every one of these bands provided a positive learning experience, he says, and were rewarding especially for the friendships he made and would later come to value.

And yet, by early 1991, Abbruzzese considered dropping the sticks. His feelings were complicated when he broke off a romantic relationship. It seemed to him, during those days, that he had done all he could with his drumming. But his only other career option seemed to be selling bongs and grow lights at the Gas Pipe. Things had become pretty stagnant.

"And then," he says, "I get this phone call."

He was asked to fly to Seattle to audition for some band called Pearl Jam. The group's drummer was former New Bohemian Matt Chamberlain. Based on what he saw of Abbruzzese's drumming in the Dallas bands, Chamberlain recommended him for the spot he was vacating to join the Saturday Night Live band.

It was August 4, 1991. As Abbruzzese left Dallas for the audition, he felt "5,000 pounds lighter." The weather in Seattle was gorgeous when he stepped off the plane. "I felt completely reborn."

If ever there were a band that could be associated with fickle Generation X--on a similar, grandly commercial scale as the Beatles and Grateful Dead are tied to their generational groups--Pearl Jam would be near the top of the list. The other, of course, would be Nirvana. Both bands sprouted in the early '90s from Seattle's alternative rock music scene and are usually categorized with the "grunge" sound, though each had a unique take on it.

At times the two bands shared such an animosity for each other, nourished by the pop music press, that opinions among fans of the bands remain polarized to this day. Most notably, Nirvana lead singer and creative driving force Kurt Cobain wrote off Pearl Jam's music as a commercialized bastardization of grunge.

That's an oversimplification that strays into the territory of hypocrisy, but his remark highlighted the difference in psyche between his band and Pearl Jam. While Cobain agonized about the enormous fame and influence he wielded, Pearl Jam, personified by Vedder, enjoyed success--but disdained openly accepting its trappings or even admitting it to themselves for fear of being perceived as a high-and-mighty rock band.

The irony is that this is exactly how the band, especially Vedder, is generally labeled, due in part to the group's publicized crusades--most notably, its high-profile challenge two years ago of Ticketmaster's monopoly of concert ticket sales. The effort resulted in a lot of press but nothing to show for it in the end besides derailing the Pearl Jam tour. And industry observers question the wisdom of the band's refusal to shoot music videos in the future, which--artistic integrity aside--are crucial to promoting awareness of a new album.

In the wake of Cobain's suicide more than three years ago, pop culture writers postulated that Cobain was the extreme example of a generation's nihilism. It could be said that Pearl Jam exemplifies that complex generation's wariness of and disdain for the same mass media that fascinates it.

"Jeff Ament said I was living like a rock star," Abbruzzese says with a chuckle. "That still conjures up complete belly laughter from me." He can't help deriding his former colleagues as "un-rock-stars."

It remains to be seen if Pearl Jam will ever be as prominent as it was during its height from 1993 to 1994, when grunge culture and its music peaked. The band's first album, Ten, released in '91, has sold more than eight million copies. Since then, numbers for the band's following albums have been impressive but steadily declining: Vs. (released in '93) at five million and Vitalogy ('94) at 2.5 million. In a recent Billboard magazine chart of the nation's top-200 album sales, Pearl Jam's latest, No Code, which debuted in early September, dived from 10th to 20th place in the span of only a week. (It did, though, hold the No. 1 spot at the time of its release).

The music industry's computerized album sales tracking service, Soundscan, lists No Code as having sold more than 367,000 copies during its first week of sales. In comparison, Vs. and Vitalogy moved just less than a million copies (950,000 and 877,000, respectively) during their first weeks. Reviews for No Code have been mixed: At worst, critics have sounded indecisive or indifferent; at best it is pretty good yet still no Ten--regarded as the band's greatest and most commercially appealing album for its radio-friendly hooks. Fans have clamored for an encore, but the members of Pearl Jam have steadfastly refused to even attempt to reproduce the sound of their phenomenally successful freshman work.

The sales numbers suggest that, besides holding onto core fans, Pearl Jam simply isn't drawing the next generation--early teens to 21. And less-than-dedicated fans have moved onto other sounds--to frat rockers like Hootie and the Blowfish. How else to explain the confounding success last year of that act with its numbing rhythms and anthemlike songs other than as a sure sign that Generation X is finally starting to grow old and mellow?

But when Abbruzzese joined Pearl Jam things were still simple..... M"There was no record. There was no nothing. Pearl Jam was nothing. Ten hadn't come out yet," Abbruzzese remembers about those early, humble days. "We went on tour when the record came out. We'd play clubs where there'd be a hundred people at a 500-seat club. We went out and we worked, and we worked really fucking hard."

He had never met the members of the band before his audition. Abbruzzese just played on Chamberlain's drum set--and landed the gig. He had no idea what he was getting himself into, because Pearl Jam had yet to attain the wide radio air play and MTV exposure that would rocket the group to enormous fame.

"Then we got on the [Red Hot Chili] Peppers tour and everything just went crazy. Went through the roof," he says, still sounding amazed.

From that point on, it was virtually nonstop touring. Ask him what Seattle's music scene was like during its heyday, and you'll be disappointed. He doesn't have an opinion, because he hardly ever saw or participated in it. The band members were too busy globe-trotting, and, if they were not, he never liked to hang out in clubs, anyhow. He liked the city enough, though, that he settled in the area five years ago and moved his parents out there, too.

Abbruzzese was one of three unique personalities within Pearl Jam. Vedder was the sullen martyr, a paradoxical individual who verbally disdained celebrity yet didn't scale back his exposure in the media. Gossard was the fair-minded, level-headed diplomat who controlled the band from behind the scenes. And Abbruzzese was the nice guy--the enthusiastic one whom the fans could approach and talk to, and who didn't mind the attention--because he still remembered what it was like to be a fan. Abbruzzese appreciated the fans and, in fact, maybe enjoyed the fame a little too much. More so than the other members of the band may have wanted him to.

"Famous people who say they don't enjoy fame are the ones who want more of it," Abbruzzese says. "It takes a lot of work to be famous. Those who don't want to be famous can just drop out of sight and, in six months, nobody will remember them or care. But they don't do this."

Shifting from admirer to being admired was more than odd--sometimes it felt schizophrenic. Abbruzzese tells how he fell into gushing fan mode when he met his idol Peter Gabriel. This, despite that by that time Abbruzzese himself was a member of an immensely popular band. (Abbruzzese remembers that, when he played in Dallas bands, he was nervous when he met Paul Slavens, singer for Ten Hands, who like Gabriel was somebody Abbruzzese admired.)

So when did things with Pearl Jam go bad? And why? Abbruzzese claims he doesn't know.

His dismissal came on August 25, 1994. That day, Abbruzzese thought he and the other four members of the band were to meet for preliminary discussions on the artistic direction they were going to take on the next album--Pearl Jam's fourth. Instead, only Gossard was present.

Gossard put it simply. Pearl Jam was looking for a new drummer.

Theories abounded after word got out that Abbruzzese was out of Pearl Jam. At first, the official word given by the band was that the split was an amicable one, with its drummer leaving to "study music." Abbruzzese felt uncomfortable with maintaining that absurd untruth.

"It made my stomach hurt every time I saw the word 'amicable.' Looking back, once it all went down, the more I thought about how--if I didn't say anything and just quietly went away--the last thing attached to my name with that band would be totally untrue," he explains. "I wanted others to know that I didn't know anything about what happened to me, either."

Fans speculated everything: Abbruzzese had a personal conflict with Vedder; his aggressive drumming style wasn't in sync with the sound that the rest of the band wanted on the next album; Abbruzzese's "Texas, pickup-truck personality" (he drives a truck and owns a couple of guns) clashed with Vedder's politically correct sensibilities; Abbruzzese wanted to tour rather than waste time taking on Ticketmaster; the Pearl Jam drummer had disagreed with his bandmates about the cover art for the band's second album; Vedder conspired all along to replace Abbruzzese with friend Jack Irons (now the band's drummer), formerly with Los Angeles funk rockers the Red Hot Chili Peppers. Basically every theory was present except the second gunman on the grassy knoll.

Abbruzzese says that he can't pinpoint why he was let go. He's certain, however, that his dismissal had nothing to do with the quality of his drumming talents--an assessment many fans and industry insiders share. Nor did he think anything was wrong with his relationship with the others in the group. But in interviews after Abbruzzese's departure, Gossard revealed--in Musician magazine particularly--that the climate within the band leading up to Abbruzzese's firing was "complex," and that the band members were unable to find a "balance, a mutual respect for each other."

Poor communication within the band was a problem, Abbruzzese admits. It may explain why he was blindsided by his firing. The best hypothesis is that he was oblivious to a growing personality conflict between himself and the other members of the band. The bad mojo probably reached its critical mass somewhere between late 1993 and toward the middle of 1994--between the release of the band's second album, Vs., and while they worked on their third, Vitalogy.

In a candid moment, Abbruzzese remembers times when Vedder threw water bottles at him in fits of frustration. He never took any of Vedder's behavior personally, Abbruzzese says, because he never imagined that Vedder meant it as a personal affront--just a professional dispute. Now--he says with an incredulous snort--he wonders if it was indeed the former. In a later discussion, he's more subdued when talking about his ex-bandmates, saying only that Vedder struck him as "intense" when they first met.

Gossard, though, made an effort to credit Abbruzzese with the development of Pearl Jam during its formative years. Ever the diplomat, he even went so far as to thank the band's ex-drummer at the Grammy Awards this year when the band won album of the year for Vitalogy, the second and last album Abbruzzese worked on. (McCready could be heard tiredly muttering "jeez...." under his breath when Gossard mentioned Abbruzzese.)

Abbruzzese says he has no regrets or grudges. "With all the time that's passed, I look back and think, it sure was great and sure was a lot of fun," he says. "And I learned a lot and still haven't stopped learning.

"I can definitely step back now and say that I might not have been the right guy for those guys all along. But at the same time, I can tell you with all honesty that they weren't the right guys for me, either, and I don't feel bad about that."

For a while, after being fired from Pearl Jam, Abbruzzese seriously considered retiring--not from music but from all the music-biz "bullshit." He continued to drum, participating on compilation albums such as a Jimi Hendrix tribute. "It was a time when I still enjoyed drumming, but I really needed to find out if there were reasons for playing music other than for the success and fame and everything. I needed to make sure that that something was still within me--the stuff that put me in the position to play with that band."

Months after his dismissal, he returned to the Dallas area to visit friends Darrell Phillips and Doug Neil, bandmates from his pre-Pearl Jam years. They teamed with David Castell (who produced for Course of Empire) and the four played around with a musical collaboration.

"I wanted to play with people I knew, knowing that there wouldn't be any bullshit attached to it. With Darrell and Doug, I could get in the studio with those guys and jam, and it wouldn't be like anybody would think that jamming with me would be anything more than jamming with me. It wouldn't be like a 'big break' for them or any of that sort of crap. It would just be three people who really like each other and want to get together and play, like we used to."

Soon, Ten Hands vocalist Paul Slavens was brought in at Castell's suggestion. Gary Muller, another Ten Hands alumnus, joined the impromptu jam sessions that were recorded at Castell's R.S.V.P. Studios in Garland. In those jams, the process usually involved Abbruzzese, Neil, Phillips, and Muller creating a beat--finding some crazy sound and going with it--while Slavens made up lyrics on the fly. The result, surprisingly, was a number of pretty good songs. Thirteen tracks were put on a CD--Play Parts I and IV--that Abbruzzese produced a limited number of copies of for friends and industry colleagues.

Considering the overall quality of this limited-issue CD, it's hard to believe these guys were only jamming. The music brings to mind an updating of the funk sensibility of Ten Hands, guided by Abbruzzese's energetic drums and narrated by Slavens' nonsensical yet fun lyrics. Ranging in average running times from three to five minutes each, the songs don't meander. They have a cohesiveness in sound and form. But none of these tunes was deliberately composed before it was performed. Except for minor post-production work and any necessary re-recording of lyrics, what you hear on the CD is what was first recorded. The liner notes for the CD don't list lyrics but instead describe each song's "birth." As an explanation for the track "So What If I Am" details: "A post-poker-game jam at 2 in the morning. Darrell started playing this slinky funk thing that inspired a late-night sort of groove thing."

Things went so well that Abbruzzese decided to set up a residence in the Dallas area to be closer to the other members. With a band name now, Green Romance Orchestra (taken from the title for a chintzy souvenir diorama of frogs holding musical instruments), he and his new bandmates envisioned a fully equipped retreat where they could conveniently continue with their late-night sessions.

Slavens scouted out a property for conversion into a "studio retreat." He discovered a 6,000-square-foot house, situated in the midst of 600 acres on the outskirts of Denton. The only access to it is a narrow gravel road. Castell moved into the "ranch"--as Abbruzzese and his colleagues call it--and combined his and Abbruzzese's recording equipment to build an elaborate studio.

The house itself is less in the traditional Texas ranch style than what could be termed more accurately "institutional hell." Wood paneling covers most of its interior walls. Hallways are long, wide, and dimly lit and have low ceilings. Bathrooms feel like public restrooms with baths. The kitchen has a restaurant vibe, an area where massive amounts of food might be prepared. The color scheme is faux woodgrain.

As Abbruzzese observes, the building's feng shui is way off. As it turns out, the building had at one time been converted to serve as a facility for mentally disabled youth.

Now, the compoundlike house has been transformed into a sprawling, state-of-the-art recording studio. One of the large rooms is cluttered with the inventory of a small music instrument shop--electric guitars, keyboards, and mikes, and plenty of electric cables snaking all over the floor.

In an adjoining large room, Abbruzzese's drums, including the white set he used while touring with Pearl Jam, are set up, ready for immediate use.

Recording command central has been established in the master bedroom across the hall where the temperature runs nearly 10 degrees higher because of heat generated by the recording and computer equipment. Sitting in front of the red and green lights of the mixing board, and swiveling in his chair to computer monitors, Castell looks like a propulsion engineer monitoring a rocket launch.

During recording sessions, Slavens often spends his time in confinement. He and his instrument--his singing voice--get shut in a tiny room that might have been the laundry or a walk-in closet.

Even though every imaginable piece of equipment and necessary amenity has been brought in to build this ideal musicians' retreat, the building's lousy feng shui may have ultimately reigned supreme. Abbruzzese feels the band's initial jam sessions in its new creative environment have resulted in a darker sound than that on the first CD.

Since April, the musicians have amassed hundreds of recorded hours of music. Every sound made near a live microphone--no matter how insignificant, silly, or bad--has been recorded, logged, and saved. Six months later, Abbruzzese and Castell are wrapping up final mixes for songs to be selected for a second CD. This will be GRO's first official album, to be released and distributed by the New York-based Madison label.

"Granted, I definitely know a lot of it is due to the fact I was in that huge band," Abbruzzese says. "But I'm not stupid enough not to take advantage of it--to not know that something really good can come out of those years."

The freight train has passed, and the group returns to the ranch house. Asked what he meant when he made his announcement to his fellow Green Romance Orchestra members that he was "freed" from Pearl Jam, Abbruzzese will only breeze over the general facts: The details of a settlement and legally binding agreement with Pearl Jam were hammered out. For two years, these matters had been lingering and weren't resolved until that day.

So Abbruzzese seems even more jazzed than usual. It's more than a sense of relief; it's a major step toward putting the recent past behind him.

He talks of plans to move out of his home in Seattle, a "crow's nest" high above the city. He and his girlfriend are looking for property in a close-knit island community near Seattle--a charming place where residents give you extra raspberries they've picked. He hopes they'll find a home with pleasing, inspiring architecture and build a quaint, little fence around the yard. Abbruzzese, who has always lived for the moment, is finally thinking about the future.

As for his new band, he knows its chances of success will depend less on his name than on the music. The niche of devotees he still has among Pearl Jam fans is curious about his new venture, but whether that translates into notice by a mainstream audience is uncertain. Based on the limited-issue CD, the band's sound has an appeal that will likely draw more appreciation by connoisseurs of rock musicianship than by a mass audience accustomed to the catchy ditties played on radio and MTV. Green Romance Orchestra is, as Abbruzzese puts it, less about songwriting than about guys wanting to jam.

"We weren't ever planning to be a band," he says. "We were just a couple of guys getting together and having some fun."

Castell takes a break from the sound-mixing chores of "Dust," one of the cuts for the CD, and Abbruzzese slides into the chair at the mixing board and listens to the playback. Wearing glasses and with his long hair tied back, he looks like a studio tech geek. He mulls over the daunting array of volume levels and LED lights.

Switching through the tracks for each of the song's instruments, he stops at the one playing his own drumming. The sound pounds through the speakers with a commanding force. It reveals that Abbruzzese's drumming skill can easily be listened to on its own, apart from the other elements that make up the song. Mixed back into the rest of the track, the beat meshes into the overall sound of "Dust"--carrying the song's rhythm without being overbearing.

As he continues to flip quickly through the tracks, both his and Castell's ears pick up something that doesn't sound like it's supposed to be there. A backtracking and search narrows down a split-second fuzzy noise on a guitar track, which Castell labels a "digital glitch." He plans to remove it through the computer, but Abbruzzese says it isn't necessary. He plays the song through the glitch-affected portion of the tape, demonstrating that it is impossible to pick up when the song is mixed.

Castell whispers not too secretly toward Muller that he'll delete the glitch when Abbruzzese is asleep. Abbruzzese smiles, telling Castell he doesn't need to go to the trouble. Besides, the glitch adds a certain uniqueness to the song, he jokes.

As Abbruzzese plays back the entire song from the beginning, he rests his head on the mixing board's armrest, feeling the song's rhythm. He knows that Castell will wipe out that glitch, despite what Abbruzzese said, as any studio producer perfectionist would.

Listening to the playback of "Dust," head on armrest, Abbruzzese doesn't look worried about anything. It's the near perfection of the song that he's taking in. Everything else in life is minor details. "I've been to a place that as a kid, as a teenager, I always wanted to go to. I wanted to experience it through music, and I did it. And it was great.

"Now it's back to reality. Now I can just play music. If that stuff or whatever doesn't happen to me again, I don't care. I've been there, and it was really good. My ego is good. Success to me doesn't involve that anymore. It's beyond that. Success isn't limos. Success isn't money. Success to me is relationships with myself and with the people I love. I could definitely be a fuckin' happy gas station attendant. No problem. I'd be a good one because I'd be pumping the gas because I dug it.