You tell me. What’s the worst school problem? Reading? Math? Football? For me the worst school problem has always been children who wind up in the pen for most of the rest of their adult lives.

Since 2007, Texas Appleseed, a social advocacy group, has been documenting the high correlation between children who get kicked out of school and children who become young incarcerated adults. Not everybody who gets sent to prison one time goes back a second and third time, but when you couple incarceration with illiteracy and then also factor in school drop-out rates, the prospects are pretty terrible. Texas Appleseed reports that 80 percent of the people in Texas prisons are school drop-outs.

You might say, sure, because they’re screw-ups. Once a screw-up, always a screw-up. But, wait. We have a pretty big, expensive and sometimes scary screw-up issue in our society. Is there any way to ameliorate that? In fact, that is exactly what a new policy on school expulsions adopted two weeks ago by the Dallas school board aims to find out: Is there a way to turn kids’ lives around?

Texas Appleseed’s annual reports on “the school to prison pipeline” document clearly that black kids, especially black boys, wind up in school disciplinary systems at the highest rates, meaning they are serially expelled from school at the highest rates, beginning at the very youngest ages, and/or they are assigned later to so-called “alternative schools,” which Texas Appleseed has shown are super drop-out factories, kind of like prison prep schools.

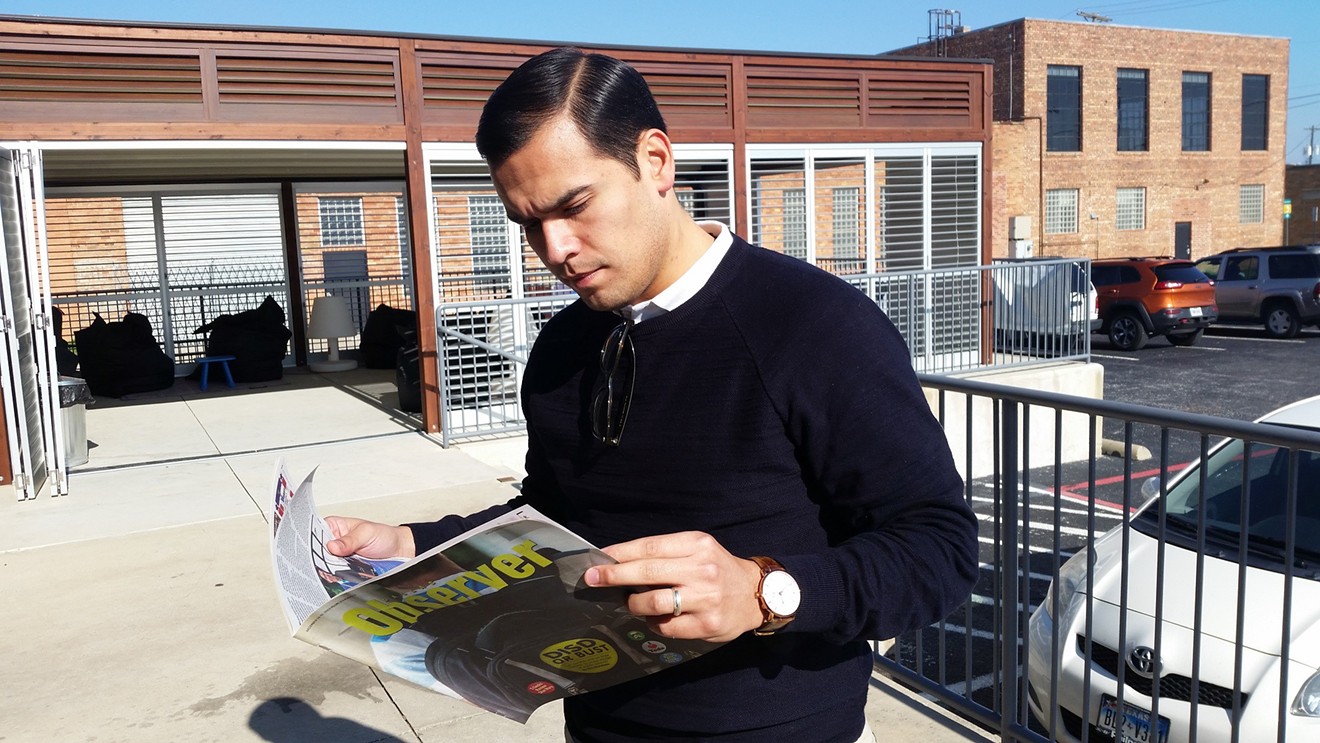

Before we assume the Simon Legree model here and reflexively blame those numbers entirely on racist white people, it’s important to recognize that tough punishment including expulsion is not without strong support in parts of black America. In Dallas last year when Miguel Solis, a Latino Dallas school board member with a graduate degree from Harvard, began agitating for a revised policy on expulsions, he met adamant opposition from black board members Joyce Foreman and Bernadette Nutall.

If there is a way to get kids out of the school-to-prison pipeline, shouldn't we do it?

South Carolina Minority Affairs

Foreman and Nutall couched their opposition in educationese and qualms about the financial costs of not expelling bad kids, but Foreman, in particular, made it plain she also just didn’t think Solis knew what it takes to discipline black kids. Foreman, who sides often with the teachers’ unions, said: “I don’t want to take tools away from teachers for classroom management.”

Solis never does the Harvard thing on his own (“Please, borrow my pencil, which, you may notice, says HARVARD on one side”), but he does look at a lot of national research including work at Harvard, UCLA and elsewhere. From those centers a body of research and thinking has emerged in recent years indicating that a lot of American urban public school education is a kind of terrible self-fulfilling nightmare for poor minority kids.

Start out assuming a little kid in kindergarten is a bad seed, treat him like one, kick him out of school right away, and, wow, you have planted a big powerful notion in his head: “I am an outsider. I do not belong here. They don’t want me.” If that’s what he already believes, his bad behavior is locked in for good.

And this is not to say that little white middle class kids from nice neighborhoods and little black poor kids from really bad apartment buildings show up the first day of kindergarten and behave exactly the same way and then it’s the school that divides them. No, of course not. The kids from the bad buildings are more trouble right off the bat.

But what if there is a way to turn that? Nobody thinks you can turn it all the way around, 180 degrees, and turn tough little streetwise kids into suburban Cub Scouts. But what if they can be turned just enough to change a significant number of their destinies?

The research Solis has been working from is drawn from a number of centers — UCLA, Duke University, the New York and Los Angeles public school systems and the Obama White House, among others. All of it points to the same conclusion. Especially in dealing with very young students, schools can help mend kids’ lives and also do a better job maintaining classroom order by introducing more positive thinking into the process.

Several rubrics produced by this research — restorative justice, positive behavior intervention, social and emotional learning — all come back to a shared starting point, which is telling the kid the school doesn’t hate him. It might be news. That kid might have practice elsewhere being hated or at least being terrified.

I’ve read through some of this research, not enough to be a student of it but enough to get a feel. You might call it touchy-feely, but it’s not, exactly, and, by the way, it is discipline. It’s not a free pass.

Under these new systems, teachers and other personnel are taught how to tell a kid that he is expected to follow the rules but that the expectation is based on the school’s desire for him to be there, stay there, be part of the deal, one of the school family. School isn’t jail. Some of these kids have uncles telling them all about jail from an early age. Someone has to tell them school is not jail. That might be news, too, especially if it’s true.

The key element is out-of-school suspension. In the last year Connecticut, New York and Oregon have passed statewide bans on kicking very young students out of school. Georgia is thinking about it. Houston, St. Louis and Miami have adopted citywide bans.

Solis originally was going for the same kind of across-the-board ban on early out-of-school suspensions. He told the board at their most recent meeting, “The initial policy that I proposed almost a year ago would have been to ban discretionary out-of-school suspensions and expulsions for grades pre-K through second grade and make them the last resort for third through fifth grade.”

Instead, Solis wound up listening to and accepting some of the reservations expressed by Foreman and Nutall. The plan adopted finally by the board will ban suspension and expulsions for lesser offenses like cheating, being disruptive, possessing a laser pointer, but it will continue to allow suspensions and expulsions for more serious infractions like possessing a knife, fighting or bullying.

The measure adopted by the board also includes training and a serious data-collecting component to see if the new system has a good effect on schools and students. Obviously if it does, the board would consider expanding it.

The educational issues in this are tough, tied up as they are in race, the politics of school reform, union battles, all of that stuff — all reasons for unending dissension. And yet, here is a notable thing to observe about the outcome, given these times, given the political atmosphere in our nation and in our city: After arguing the school discipline issue for six months, the Dallas school board at its last meeting voted to adopt the compromise package by a vote of nine to zero. It was unanimous.

Texas Appleseed reports that 80 percent of inmates in Texas prisons were school drop-outs.

Jared Boggess

The 9-0 vote is a tribute to the leadership of Solis, who knows how to do politics without making it personal. Foreman and Nutall deserve kudos, too, for pressing their case and then accepting reasonable compromises.

But mainly, just think about it. This is the Dallas school board. It wasn’t that long ago that the Dallas school board was almost a national poster child for dysfunction. They could have adopted as their behavioral motto for the kids, “Don’t Act Like the School Board.”

They just voted unanimously on a tough question. So doesn’t that mean, if they can do it, anybody should be able to? Almost anybody? Maybe a short list of exceptions? Real short?