All the more appalling for the owner of it to have been the public school system, whose No. 1 priority ought to have been helping the neighborhood get better in order to help the kids.

No, I don’t mean help the kids. That’s a gross understatement. Let me put that another way. Save the kids’ lives. That’s what the public schools ought to be doing. Because what’s the point in teaching ABCs to a kid in a government-engineered concentration camp where the graduation ceremony is a prison sentence?

This is not an all-bad-news column, by the way. I even have a happy ending in mind, if I ever get there. But first we need to get down on Pearl C. Anderson Middle School. Now a ghastly eyesore, Pearl C., as it is commonly known, was closed by the Dallas Independent School District in 2012 and left to rot in place. DISD could not have chosen a worse place to let that happen.

Pearl C. is in postal ZIP code 75215. That area is a boxcar on the cradle-to-prison railroad. According to numbers recently published by Commit!, a nonprofit education advocacy group headquartered in Dallas, 75215 has the highest percentage of any ZIP code in the city of adults 18 and over now serving time in Texas prisons.

It is one of a group of only 30 ZIP codes in Texas — less than 1% of all postal zones in the state — that account for more than 12% of the state’s prison inmates.

Pearl C. Anderson Middle School is in postal ZIP code 75215, a boxcar on the cradle-to-prison railroad.

tweet this

Of approximately 56 ZIP codes in Dallas, 75215 is among eight at the top of the list for sending residents to prison. Of those eight, 75215 has the second-highest poverty rate, the second-lowest median earnings, and it is tied for last in the number of high school graduates who are prepared for college. This is the last place in the city, maybe the last place on earth, that needed a big, rotting building to remind everybody how screwed it is.

You may tell me, Oh, come on, man, the last place on earth? There are lots worse places on earth. Yeah, but why? This particular place is a children’s graveyard for a very specific reason, and the reason is what counts.

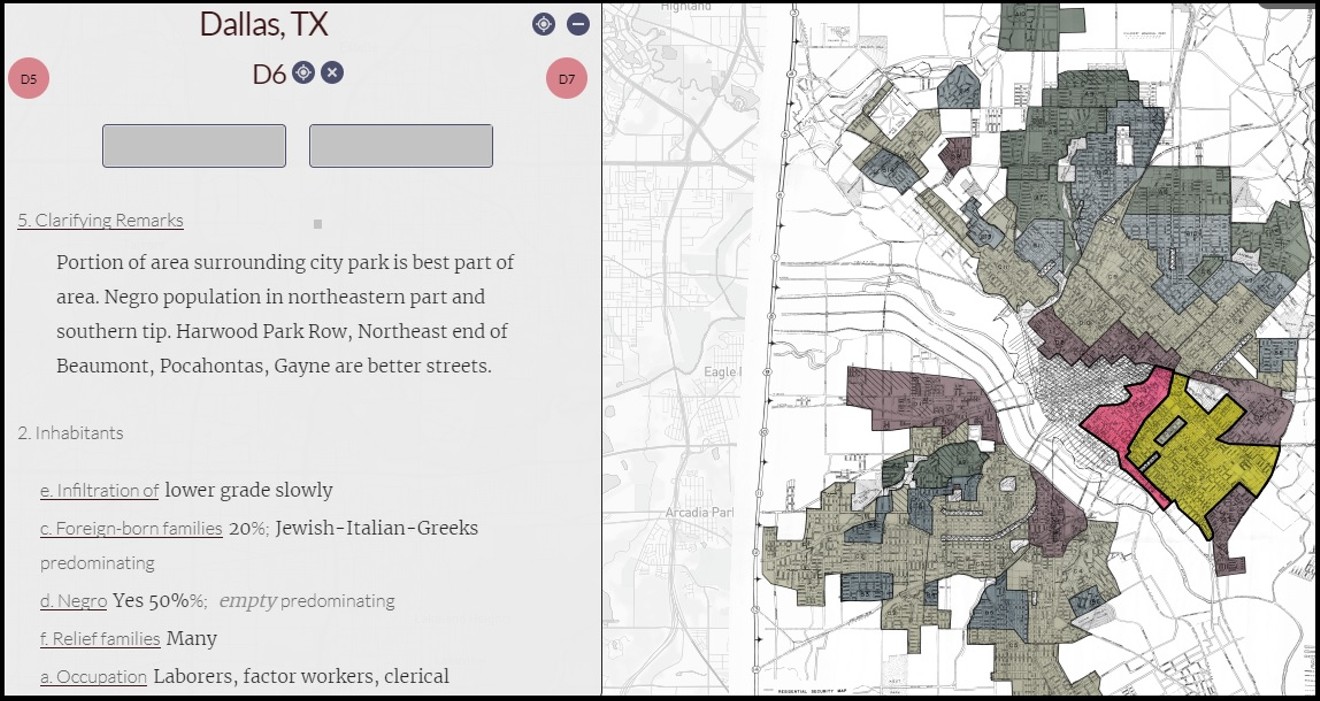

The 2019 map of the cradle-to-prison Dallas ZIP codes published by Commit! is eerily consistent with the red-lining maps published by the federal government’s Home Owners Loan Corp. between 1935 and 1940. For many long decades, those maps had everything to do with where banks would and would not make mortgage loans.

Today’s 75215 ZIP code covers two areas on the 1940 HOLC map of Dallas. One was colored yellow, for “definitely declining,” and the other was red, for “hazardous.” A hazardous zone was one with more than 50% black residents and/or a significant number of Jews, Italians, Greeks or families on welfare.

The red-lining maps were a powerful signal from the national government that resources were to be withheld. That signal was replicated and amplified throughout government, including state and local government. It meant less investment in basic infrastructure, less fire protection, less public health, less law enforcement, less education.

Over a long enough period of time, an official policy of consistently providing less of everything to a specific community has a specific effect, shown clearly in those cradle-to-prison numbers. Other places on earth may be more poor in absolute terms, but the poverty and suffering of 75215 were inflicted on it deliberately by official policy in a rich country.

ZIP codes 75216 and 75217, just south of 75215, have the highest inmate totals of any ZIP codes in Texas. The percentage of adults in 75216 who are inmates is 36 times greater than the percentage in 75225 in the affluent enclave community of Highland Park.

Yes, thousands of ambitious, hard-working families have escaped those ZIP codes. But the areas haven’t changed, and the babies born into them don’t have a choice. They are born behind a social fence, the communal equivalent of barbed wire. They grow up to look out through that fence, where they see a better world. They are too often already barred at a young age from that better world by partial illiteracy and criminal involvement.

In his 1852 novel Bleak House, Charles Dickens described the sufferings of the London slum he called Tom-Alone. “But he has his revenge,” Dickens wrote. “Even the winds are his messengers, and they serve him in these hours of darkness.”

After seven years of malign neglect, Pearl C. has been purchased by a suburban megachurch with a fairly spooky reputation for things that sound like mind control. The church seems to be awash in money, so a little spookiness may be a small price to pay for getting the roof repaired.

In the meantime, this is the problem with citing the full bleakness of 75215 all at once as I have done here so far (remember, I promised a happy ending?): The sheer impervious bleakness of these problems can quickly become an excuse and self-fulfilling prophecy of failure. That’s something we hear too often anyway from certain voices within public education: If it’s that bad at home, what do you expect us to do about it in the classroom?

Dallas school trustee Miguel Solis is thinking of ways the school system can offset the historical effects of red-lining.

Jim Schutze

But let’s be real. None of that stuff gets to the cradle. Let’s say somebody invests in an airline food-processing plant in 75215, and somebody else trains people to work there. Nobody who got kicked out of school at 13, went to juvie at 15 and was in prison by age 19 is going to work there.“But he has his revenge. Even the winds are his messengers, and they serve him in these hours of darkness.” — Charles Dickens

tweet this

Who saves the lives of those kids? And if you repopulate the ZIP codes with a kind of kid who doesn’t have those problems, where does the kid go who does?

The happy ending is this: In spite of everything I just got done saying about DISD and Pearl C., the most innovative thinking about social change in the city right now is taking place not at City Hall (at all) and certainly not in county government but within school leadership. If we give DISD a big goose egg on Pearl C., we also need to acknowledge the exciting progress the schools have made with things like the teacher excellence initiative (merit pay), the Accelerating Campus Excellence program (ACE schools) and choice schools.

All of these have been successful efforts to marshal resources within the walls of the school system and direct those resources to schools within the city where help is most needed. These efforts all express a much more intentional focus on social justice than we see anywhere else in local government.

But what about that world outside the walls, the bleak streets of 75215, 75216 and 75217? Who is going to take on the kind of positive social effort needed there to redress the effects of decades of negative government social engineering? Maybe the answer is going to be the school system again.

School trustee Miguel Solis has been working with City Council member Adam Medrano for five years on a program just now coming into being in which special high schools will prepare students for careers in law enforcement. It’s a brilliant idea at several levels.

Kids need good jobs. The city needs good cops. But this city also badly needs to forge a new social bond between its citizens and its police force. What better way for us to do it than by growing our own?

When I saw an op-ed piece by Solis recently explaining the idea, I was reminded of another of his ideas a couple of years ago when the school district was selling off its obsolete headquarters property on Ross Avenue a mile northeast of downtown. Solis pointed out that elementary schools near the old headquarters were depopulating and closing as gentrification of East Dallas forced poor and working families to move out of the area.

Rather than simply sell the property to the highest bidder, Solis proposed that the school district redevelop it as low-income housing. Providing good, stable housing for the struggling families of students, he suggested, was a valid and effective way for the school district to carry out its mission.

Everybody thought he was nuts. “No,” they all said. “Get the best price we can. Put the money in the bank.” But wasn’t Solis really thinking ahead of the curve?

The egregious social outcomes we see on the ZIP code map today are products of massive government action and policy over decades. Would it not be proportional and effective for government to take purposeful action where it can to redress its own sins? And given our reflexive vigilance against government intrusion everywhere else, are the public schools not the best doorway we can find into the lives of children and communities?

In fact, the way Solis and Medrano have focused on community outcomes might even serve as a guidepost for much larger systemic change. For example, consider the $3.5 billion bond issue that DISD is going to ask us to approve at the polls next year. What will that money be for? What purpose?

Buildings? Hey, I wouldn’t say buildings are the school district’s strong suit. What if the school board gave us a bond program instead aimed at social change? They could even draw lines around the areas they want to use the money to improve. We could call it gold-lining.