"Hello!" Bailey called out, over the roar of traffic nearby on U.S. Highway 75.

Hundreds of volunteers spread out across Dallas and Collin counties Thursday night for the annual Point in Time homeless count.

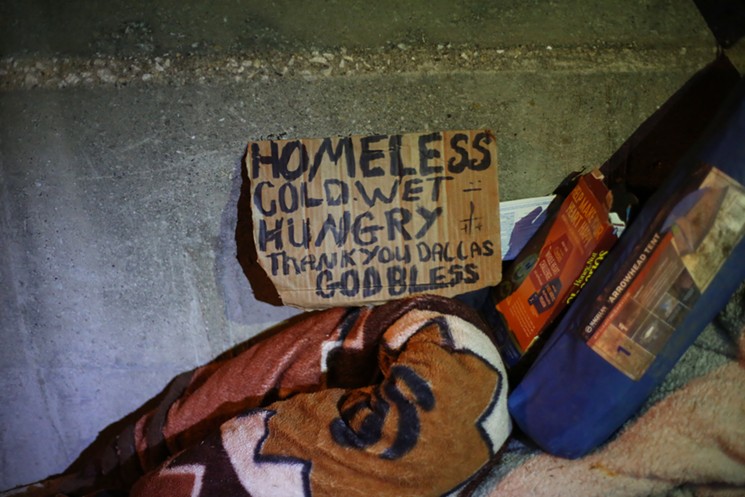

Dylan Hollingsworth

Bailey called out again. After a moment, a flashlight beam appeared. A few seconds later, a man appeared on the path at the edge of the woods and greeted Bailey and the group of volunteers who were with him.

Bailey, an outreach worker for Metrocare, a Dallas-based behavioral healthcare provider, explained that the group was part of the city's annual Point in Time homeless count. He asked the man, Chad Garcia, if he'd be willing to take a survey. Garcia agreed, and Bailey pulled up the questionnaire on his cellphone.

As the two men talked, a black kitten poked its head out of the brush on the side of the trail, looked around, then walked up to each of the volunteers, one by one, to see who and what they were. Hope Stedman, Metrocare's clinical manager for homeless services, bent down to pet the kitten, which arched its back and rubbed on Stedman's leg appreciatively.

Once they were done with the questionnaire, Garcia, 34, told Bailey about a few other camps he knew in the area. Bailey handed Garcia a care package full of toiletries and other supplies, the two men shook hands and the group walked off.

The three volunteers in Bailey's group were among hundreds who spread out across Dallas and Collin counties Thursday night, administering the same questionnaire to any homeless people they found. Others gave the same survey to people staying in the city's homeless shelters. Cities across the country conduct similar homeless censuses each year on chilly nights in January, in the hopes that the weather will drive more people off the streets and into shelters, where they're easier to count. Those cities report those numbers to the U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development and use them to inform their own homelessness policies and systems.

Josh Thomas, 21, said he came to Dallas from Rochester, New York, to live with his grandmother. When she died, he was left without a place to stay. So he slept on friends' couches for a while until he was arrested on a burglary charge. When he got out, he had nowhere to go, so he ended up on the streets.

Dylan Hollingsworth

Sleeping Rough

Numbers from Thursday's census won't be available until March, but over the last decade, the number of people sleeping on Dallas' city streets, under overpasses, and in parks and patches of woods has shot up drastically, leaving city officials and homeless advocates alarmed.

Between 2009 and 2019, overall homelessness climbed by about 2.26% in the Dallas area, according to figures collected during the Point in Time count during those years and reported to HUD.

But during that same period, the number of unsheltered homeless people in the city — those living outdoors, in places not meant for human habitation — ballooned by 725%. In 2009, outreach workers and volunteers counted 176 unsheltered homeless people in the Dallas area. Last year, they counted 1,452. Advocates estimate the actual number of unsheltered homeless people in the area for the entire year is three to five times the number tallied during the Point in Time count.

Advocates point to a number of issues as possible drivers of that growth, including insufficient funding for homeless outreach programs and landlords who are unwilling to rent to low-income tenants. But mostly, they say, a lack of affordable housing in the area is preventing people who are homeless from moving out of shelters and into housing and throwing others who live on the economic margins into homelessness.

Although he was one among hundreds of volunteers Thursday night, Bailey's job with Metrocare takes him out to homeless encampments nearly every day. Over the last few years, he's noticed camps popping up in places where they didn't exist before. Years ago, they mostly showed up downtown, near homeless service providers. Now, he said, many more are showing up farther north, including in some of the areas Bailey's group searched Thursday night. He wasn't sure why.

"Above my pay grade," he said.

Hope Stedman looks over an abandoned homeless camp under a highway overpass near the Lyndon B. Johnson DART station.

Dylan Hollingsworth

Thomas said he thought he could get himself into housing if he could get a copy of his birth certificate and his Social Security card. Bailey told Thomas he'd be back by on Monday to follow up with him.

Bailey said Thomas' story about just needing to get copies of his personal documents is one he hears often. Many people tell him they ended up on the streets after their ID or Social Security card was lost or stolen, and they couldn't get work. Usually, there's more to the story than that, he said, but at least it's a place to start.

The group moved on, working its way through a string of camps along Cottonwood Creek. As they picked their way down an embankment under a footbridge, they came upon a small group of tents arranged around a fire pit, where a few embers glowed from a nearly dead campfire. Bailey called out. A voice from inside one of the tents told him to get lost.

"I'm surprised we don't get that more often, to be honest with you," said another volunteer, Ikenna Mogbo, Metrocare's director of homeless services, housing and veterans services.

A Broken System

Like most major cities, Dallas has a system in place for helping get people off the streets and into permanent housing, said Carl Falconer, president and CEO of Metro Dallas Homeless Alliance. If that system were working as it should, people would move from the streets into emergency shelters, where staffers would assess what their needs were. Depending on their circumstances, they might move from emergency shelters into any of three types of housing: transitional housing, rapid rehousing or permanent supportive housing.

People who move into transitional housing or rapid rehousing usually don't stay there more than a few months, Falconer said. People in those programs are generally between the ages of 25 and 45. They're usually able to work — and in many cases, they do work, Falconer said — but they can't afford to get themselves into housing without some help. While they're in the program, they get financial help and any other services they need, and once they're stable, they move out of the program and into ordinary housing.

People with bigger needs like disabilities, mental health issues or addiction generally go into permanent supportive housing. That's a longer-term program — usually two years or longer — that involves housing along with intensive therapy and other services to help them with whatever issues are keeping them out of housing.

But in Dallas, two main factors keep the system from working the way it's supposed to, Falconer said. The first is a lack of rapid rehousing. The city has a healthy stock of permanent supportive housing — as it should, Falconer said, since those units are designed for the most vulnerable people. But people who need rapid rehousing can't get into permanent supportive housing, because they're not disabled and don't have any of the other issues that would qualify them. Instead, they end up stuck in emergency shelters, waiting for a rapid rehousing unit to open up.

The other factor is that people aren't moving through and out of permanent supportive housing as quickly as they should be. Although people could theoretically stay in permanent supportive housing for the rest of their lives, the goal is generally to stabilize them and move them out into homes of their own. When people don't move out of permanent supportive housing, other people can't move in, Falconer said.

The reason people aren't moving out of permanent supportive housing is that there's a serious lack of affordable rental housing in Dallas, Falconer said. The people who are in permanent supportive housing generally can't work. Their only income usually comes in the form of a Social Security check. So even after they no longer need the services that come with permanent supportive housing, they stay there because they can't find any other housing where they can afford the rent.

To try to mitigate that issue, Metro Dallas Homeless Alliance is working on a project that gives housing vouchers from local public housing authorities to people who are already in permanent supportive housing. Those vouchers allow people who no longer need services to move out and live on their own, and people who need those services to move into permanent supportive housing, he said.

The high cost of housing is also leaving people stuck in shelters when they're ready to move out into their own homes, said David Woody, president and CEO of The Bridge Homeless Recovery Center.

When a person comes to the center, staffers there give them an assessment to figure out how they got there and what approach would work best for helping them pull themselves out of homelessness.

The Bridge embraces a recovery model called housing first, which involves placing homeless people into housing then giving them whatever recovery services they need, rather than asking them to go through a defined recovery program before being allowed to move into their own accommodations. It's an approach used by most homeless advocacy groups in Dallas and across the country and supported by HUD.

The problem, Woody said, is that if there isn't enough affordable housing in the city, advocates can't even complete the first step of that process. There are about 100 people living at The Bridge who are ready to move into housing, Woody said, but staffers there can't find affordable rental homes for them.

"That concept is awesome if housing exists," he said. "That's one of the challenges."

‘It’s a Family’

After speaking with a pair of men living in a camp tucked back into the woods along the creek, the volunteer group doubled back and stopped at another camp along the trail. They'd stopped by minutes before but found nobody. This time, they found Garcia and Thomas, the two men they'd met just minutes earlier. Garcia said that city workers had come by a few days earlier and told them they'd be by in a few days to roust them. They were trying to gather what they could to get ready to move.

The camp was in a clearing cut in the middle of a stand of bamboo. About a dozen shopping carts lined the perimeter, and a tent large enough for several people to stand comfortably inside was set up to one side, with cots spread out inside of it. In the middle of the clearing was a fire pit ringed with stones. There was no fire, but the smell of wood smoke still hung in the air. A pop-up canopy was set up above the fire pit, and on one corner, within easy reach, hung a fire extinguisher.

Chad Garcia said he'd been living on the streets since April. A group of volunteers found him Thursday night in an encampment near Cottonwood Creek in Northeast Dallas.

Dylan Hollingsworth

Garcia said he'd been on the streets since April. He'd once worked as an oilfield crane operator, but he said his ID, Social Security card and birth certificate were stolen, leaving him unable to get a job. If he could get those back, he said, he could get back to work and get off the streets.

Most people who have never been homeless don't understand how hard it is, Garcia said. When he was working, he worked hard. But now, he has to work even harder just to find food every day and a warm, dry place to sleep every night, and while he's trying to survive, people treat him like trash, he said.

But if they don't get much attention and understanding from the outside world, there are strong community ties among the people living in the camps. Although the two men aren't related, Garcia called Thomas his "street son." There are about 15 people living in the camps nearby, and they all keep an eye out for one another, Thomas said. When someone is new on the streets, one person will introduce them to another, who introduces them to a third. Soon enough, they're a part of the community, he said.

"It's a family," Thomas said. "We all treat each other as family."