Nor does it do any good, even in the wake of the recent scathing report from the University of Texas at Arlington, to try to make out that DART is run by a bunch of crooks. It’s not.

Sure, there has got to be some good reason why DART has spent $5 billion of our tax money, with $2.3 billion more soon to come, building the nation’s longest light rail system, when, as the UTA report revealed, the system has one of lowest rates of ridership per mile in the country. How did that happen? Somewhere back around $4 billion, shouldn’t someone have looked up from her desk and said, “Hey everybody, look! Nobody’s ridin’ that sucker!”

But that answer is not going to fall within the topic of mere hanky-panky. The truth is that, in its 34 years of existence, DART has been relatively corruption-free compared to most entities of its size and spending power. People who have dealt with DART’s professional staff, including me, will tell you that DART staffers tend to be several cuts above garden variety — highly competent straight-shooters. That’s not where the problem lies.

And by the way, what’s the problem? The only way to frame the problem is by looking at the map. What has DART built? It might help to mentally visualize that map of light rail as if it were not a railroad map at all but a map of money. Instead of rail lines, pretend you are looking at bundles and bundles of cash, billions of dollars spent on construction, stacked in lines across the physical topography of the region.

Where is all that money headed? Why? What’s it trying to get to? In neither of its two basic orientations — one direction fanning north, the other fanning south — does the rail system seem to be aimed at concentrations of riders.

If all of that money were looking for fare-paying riders, it wouldn’t be reaching out with long fingers into all of those ridership dead zones. Instead, it would ball up like a fist around the densely settled areas where riders live and where the jobs are, with connectors in between. So why, instead, is the money meandering all over the joint?

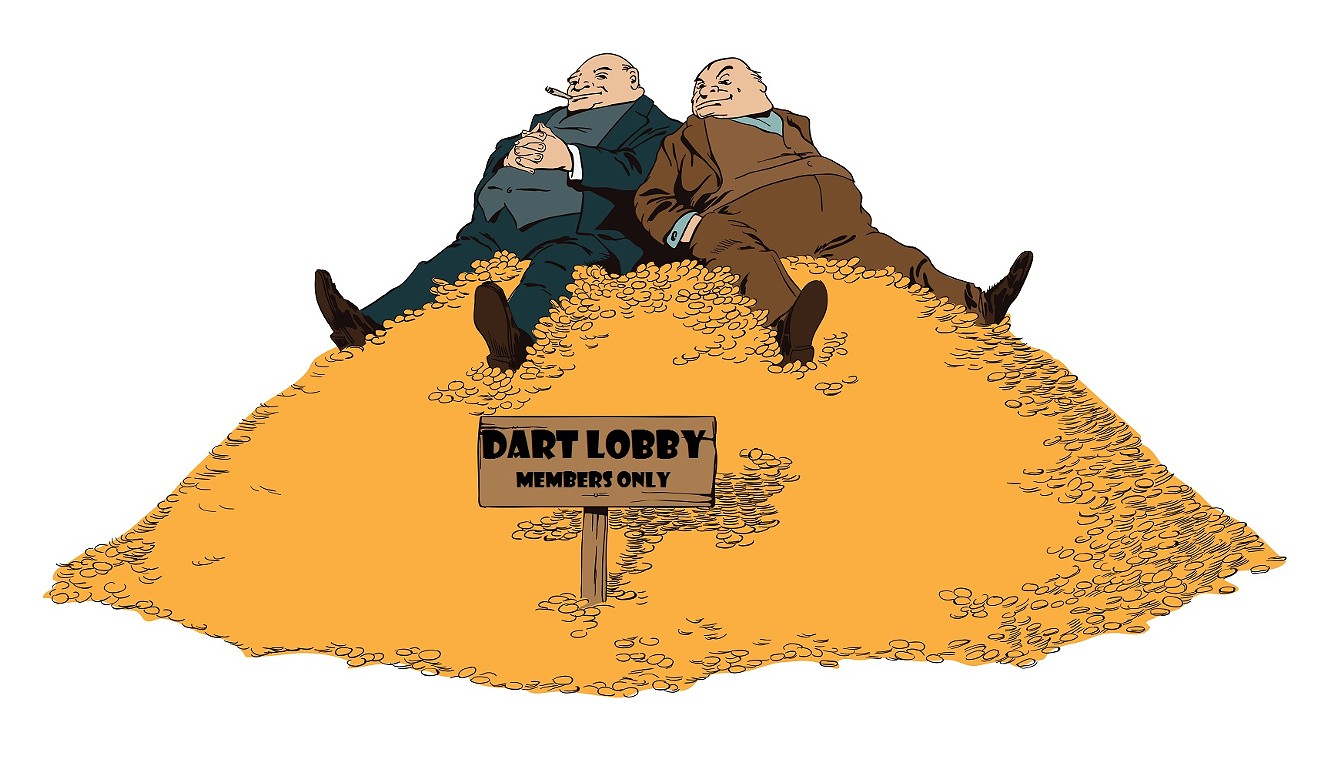

The solution to that riddle lies in the beast itself. DART is basically a mountain of money guarded by Cub Scouts. With a budget of just under $1 billion to spend every year, the DART staff answers to a 15-member board of directors, and this is where the mischief begins.

Instead of rail lines, pretend you are looking at bundles and bundles of cash, billions of dollars spent on construction, stacked in lines across the physical topography of the region.

tweet this

DART board members are appointed by the city councils of the member cities. Let me tell you something about that. That means that most DART board members are appointed by people who will never think about them again and probably won’t even remember their names unless something big comes up.

City council people have funerals and barbecues to go to. They have long lines outside their offices and in their phone mail queues, voters waiting to rail at them over garbage pickups and yield signs. Council members don’t sit around thinking, “Oh, here’s an afternoon off. I think I’ll spend it dialing up my DART board appointee so we can do some joint wool gathering on long-range transit planning.” That never happens.

Instead, most DART board appointees are sent on their missions sort of like the astronaut characters played by Sandra Bullock and George Clooney in the movie Gravity: They get cut loose, and then they drift out into space and see what’s up.

Add to that the fact that most of them are political novices. I know we live in an era when a lot of people think lack of political experience enables a kind of political purity. I happen to think that’s like believing ignorance and innocence are the same thing. But be that as it may, the fact is that people who have never occupied public office before — especially people who didn’t have to run for election to the office they’re in — do not have the thick hide or the bone structure they need to stand up to certain kinds of pressure.

There’s a particular kind of hide and bone structure that people acquire only in elective office. One term on a city council, and a person is changed forever. No terms: You’re a soft target.

Whose target? In the next five years, DART plans to spend $2.3 billion on new construction. That’s $2.3 billion that will go into the hands of a small army of public works construction companies, land flippers, dispensers of political patronage, consultants, designers, planners, and a very fortunate few buskers and tarot card readers. That’s a mountain of money $2.3 billion high, with an army of hungry seekers standing all around, doing the little cupping please-please-come-to-mama thing with their outstretched hands.

The come-to-mama people are called the lobby. Then you have the staff. Then you have the perplexed astronauts. The way this all works out in the real world is this: The staff, made up of highly competent and professional salary earners with retirement as their lodestar, gobble down the new board members pretty much the day they get appointed.

In the language of government, this is called “capture.” The staff members capture the new board members in many ways — by flattering them, by overloading them with detail, often by honoring them — making them feel as if they, the board members, have come to work for a great organization, rather than the other way around, the organization coming to work for a great board. Next thing you know, the board members are all sitting in pews being led in uplifting song by the staff.

So does that mean the staff is in charge? Oh, no. No way. Long before the staff captures the board, the lobby captures the staff. Remember that the lobby is stalking a much bigger prize — no mere sinecure or retirement package but $2.3 billion in payout over five years. The lobby tends to be intensely focused, ferociously determined and maybe even a tad ruthless if need be.

The staff knows that. They see it. They get it. They make their basic accommodation with the long knives, not the Cub Scouts. Long before the staff takes over the board, the lobby has already taken over the staff.

That means that the lobby drives whatever passes for long-range planning and policy. If you look back at our map of money, all of a sudden, some of those long-meandering fingers to nowhere begin to make sense. They were fingers to somewhere all along — fingers to where the public works construction/land-flipper/consultant lobby wanted the money to go. To them.

That’s how you wind up with the nation’s longest light rail system and nobody on it half the time. It doesn’t have riders because it wasn’t built to capture riders. It was built to capture money.

That’s how you wind up with the nation’s longest light rail system and nobody on it half the time. It doesn’t have riders because it wasn’t built to capture riders. It was built to capture money.

tweet this

So isn’t that corruption? Doesn’t that mean there’s a bandit in there somewhere? I don’t think so. I doubt anybody had to break a single law to make it come out that way. It’s not corruption. It’s human nature. Put a mountain of money out on the street in front of your house and go back inside; somebody’s going to come pick it up, are they not?

But if the problem is in the structure, then so is the solution. The answer is to pull all of this back in close, put it on the table where we can see it, put somebody in charge, and then hold him or her accountable. All of this regional hocus-pocus with appointive board members simply guarantees that the entity will wind up weak-eyed, thin-skinned and knock-kneed — prime pickings for the lobby.

The city should have its own transit authority, shared with at most a small group of inner-ring suburbs with which we have a genuine demographic trust. The new thing, whatever it’s called, should have an elected head with strong chief executive powers and a three-year term of office. Every time the public sees rail construction headed in the wrong direction or just thinks there are too many bad-smelling people on the trains, the voters should drop-kick the CEO through the goal posts and get a fresh one.

Somebody will tell me, “Oh, that might be bad for our perception of stability.” I’d be willing to pay that price in exchange for a perception of riders.

Mainly, we need to realize that the structure we have on the ground now, called DART, is not viable. Forget about anything and everything DART may tell you about its past or promise you about its future. Look at the map. The map doesn’t lie, more's the pity.