We’re hearing a lot of rhetoric about the new city manager hiring some new housing officials as if that’s going to turn things around for poor people. No, it’s not. And I am not accusing the city manager of being two-faced. His efforts are to be applauded.

But come on. The city manager and his employees work for the City Council. The Dallas City Council does not want more affordable housing. It wants less. And that’s what it will get, no matter whose name is on the city manager’s office door at any given moment.

Here’s a hint. Even when city leaders try to speak sweetly about poor people, they unwittingly express their true agenda. In his recent speech summing up the past five years of his economic growth program for the minority community, Mayor Mike Rawlings said, “One of the issues we’ve got in southern Dallas is we’ve got too many rental properties and not enough home ownership, and so we’re increasing that.”

More homeownership might work out well for middle-class workers. But poor people don’t own homes. They rent at the lowest rates they can find. That’s how they survive. Decreasing the stock of inexpensive rental property is a way to push poor people out of the city. And that’s what Dallas wants to do.

I might not even have such a hard time with it if city leaders could at least hike up their trousers, stick out their chins and say it: “We don’t want poor people.” Instead, not only do they duck for political cover, but they even try egregiously to camouflage their real agenda of expurgation, painting it as if it were some kind of twisted sympathy for the poor. Spare me a big one.

Last October, at the behest of the real estate lobby, the Dallas City Council shot down a measure that would have banned discrimination by landlords against people who use federal vouchers to pay their rent. Urged on the city by the U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development, which pays for the “housing choice” (Section 8) vouchers, the “source of income” discrimination measure probably was the best opportunity the city will see for some years to expand the pool of available low-income housing.

The mayor, who led the successful effort to tank the ordinance, hung his hat on a recently passed screwball state law saying Texas cities aren’t allowed to ban discrimination – like that’s real or will last 10 seconds in federal court. When the council voted instead for an absurdly watered-down measure, council member Jennifer Staubach Gates said she was opposed even to that half-measure. And it was her concern for the poor, don’t you know, that made her do it.

“It's going to go against state law and get tied up in courts," she said, “and people will stand there with vouchers and still not have homes.”

Oh, right. I guess ever since then, Gates, whose husband and father are high-end, multifamily real estate developers, must have been been out on the hustings bravely campaigning for a more robust way to force rental companies to accept vouchers. I guess the moon is made out of Cheetos, too.

This is not to say there are no people at City Hall or in leadership who want to see a more just and stable housing market for the working poor. Dallas City Council member Scott Griggs has been laboring for the better part of a year to bring an equitable, comprehensive housing policy to the council. Council member Philip Kingston led a brave but ill-fated campaign a year ago to create what is called inclusionary zoning in Dallas. His defeat was a good example of what’s really going on.

In New York, Mayor Bill de Blasio has made inclusionary zoning the centerpiece of an ambitious affordable-housing program. It’s basically a win-win bargaining tool for cities dealing with developers who want to build more units on one piece of land than the law allows.

We’re talking about zoning law, which is well within the purview of city councils to amend. In other words, the council can change the law at the stroke of a vote and give developers some or all of what they want. Under inclusionary zoning, before the council gives away the company store, it is required to ask for a little something in return for the people in the way of affordable-housing units.

Let’s say you are Developer A. You have the right to build 100 apartments on your land. You want to build 200 units and double your profits. The council says, “You can build 150 more than the existing zoning allows but only if you will agree to make 30 of those units available at affordable rents for 20 years.”

If that deal doesn’t work for you, just say no. Build the 100 units you bought the land for. There is no compulsion. Only do the affordable deal if it pencils out as a money maker for you.

The use of inclusionary zoning in New York and other cities around the country is more crucial now than ever. It seems clear the Republicans in Washington will squeeze down the decades-old flow of federal housing money to cities, maybe not an all-bad thing when you look at the waste and fraud. But if a city really wants affordable housing, it will have to figure out how to get a lot more of it done and paid for locally.

State Rep. Eric Johnson has an idea that would protect and sustain existing affordable-housing stock.

Mark Graham

His bill would have carved out a portion of the enormous tax subsidies cities like Dallas provide to high-end developers. Dallas City Hall is giving a subsidy of $45,000 per unit to a high-end project being developed in West Dallas by council member Staubach-Gates’ father, for example. Johnson’s bill would have carved an amount out of that to improve and stabilize poor neighborhoods threatened by gentrification.

Needless to say, the developers doing the threatening in Dallas trotted down to Austin on their tippy-toes to testify against the measure, which ultimately died of a knife in the back on the House floor. The generous view of the opposition would be that developers didn’t want to share any of their subsidy money. The less generous view would be that they didn’t want to see anything done that might have slowed down the inexorable march of geographic cleansing that they are behind.

There is nothing in Johnson’s idea to stop the Dallas City Council from adopting it as a local ordinance, even if it didn’t become a state law. The City Council votes on and creates all of these special tax district vehicles that are delivering billions of dollars in subsidies to private developers. It is within the council’s power to change those arrangements and use them to accomplish some of what de Blasio seeks to do in New York – create truly affordable, decent housing for honest, hardworking, rent-paying families.

But that will only happen here when the balance flips on the Dallas City Council, when eight of the 15 members are people who truly want decent, affordable housing in Dallas instead of abhorring the idea. Now, I count six. The four African-American seats are lost to this cause because the people who occupy them take their money from the real estate lobby.

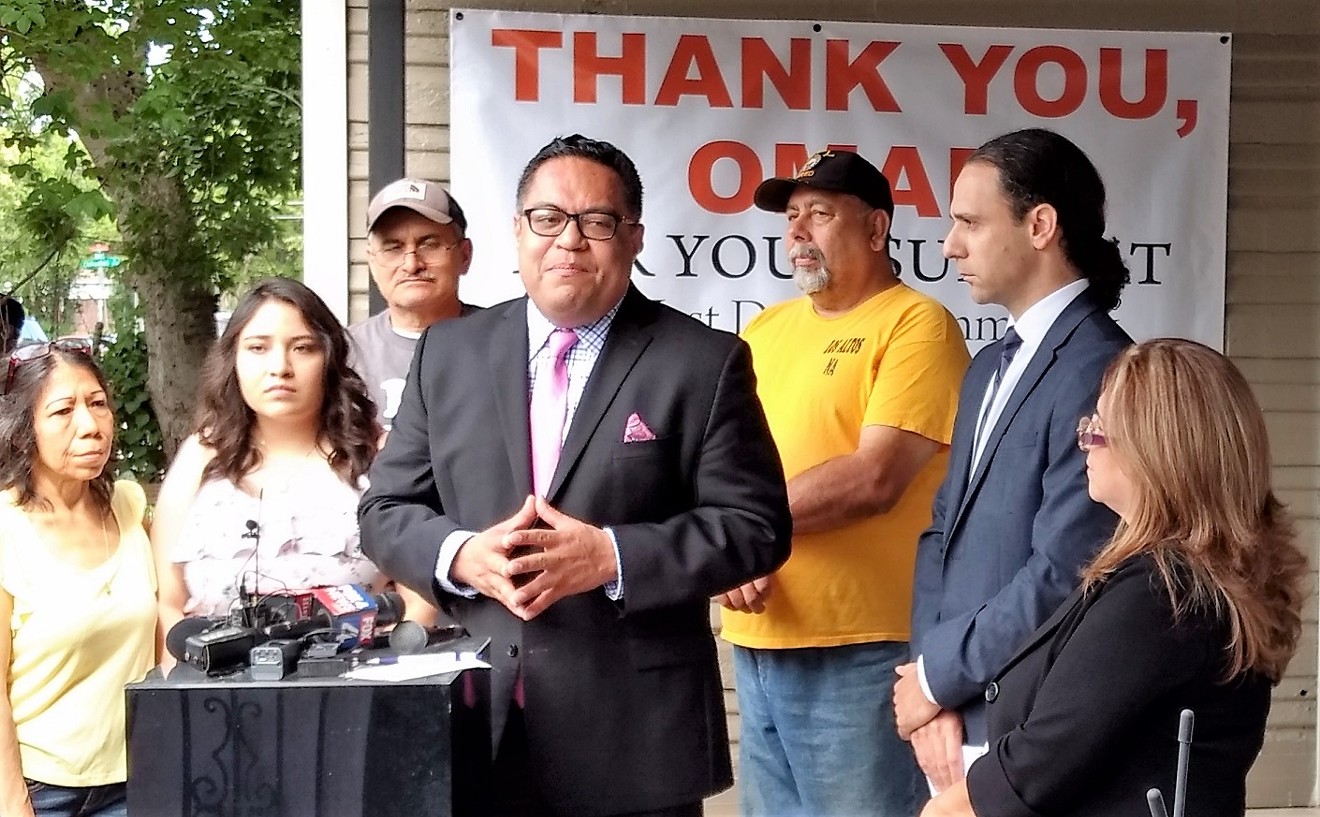

If Omar Narvaez takes the West Dallas seat away from mayoral ally Monica Alonzo in the June 10 runoff, then the number of votes sympathetic to affordable housing will be at seven. It’s conceivable that black council member Dwaine Caraway could break his lifelong connection to the downtown business establishment and move across the aisle to the people’s side, creating an eight-vote majority in favor of housing. Anything can happen in America.

But let’s say none of that happens. Narvaez loses. Alonzo holds the West Dallas seat for the mayor’s camp. Caraway thinks about going people, but somebody on the private Dallas Citizens Council offers him a better deal. The council majority opposed to affordable housing stands.

Then it doesn’t matter who is the new city manager or whom he hires to sort out the city’s housing department. Maybe they can tidy up the books, sweep some bones out of the closets and get the deck chairs lined up straight. But the Good Ship Affordable will be headed for the same iceberg, and the smart money will not be on it.