The Sotelo organization was the Sopranos of north Fort Worth, unloading “keys” of cocaine in the ’80s and early ’90s when crack infested Dallas and Fort Worth. Federal, state and local law enforcement agents spent a year in ’93 and ’94 investigating the organization and identified several key players. But it was Drug Enforcement Administration Special Agent William Travis who brought the organization down in January 1995 shortly before he was forced out of the agency. It’s a takedown that still weighs heavily on the family’s mind more than 20 years later as they gather to discuss Edward “Eddie” Sotelo and his brother “Baby” Joe Sotelo Jr., both serving life sentences in federal prison.

Patsy, 60, persuaded her mother, Mary, about a year ago to allow her to turn their family home on East Bluff Street into a Mexican restaurant.

“I always had a passion for cooking,” Patsy says. “Since I didn’t have kids, I was always the cook of the family. I thought that if we did something like this, then maybe we could earn some money to try to help my brothers come home.”

But the Sotelo brothers have exhausted their appeals. They watched from their prison cells as President Barack Obama released more than 1,000 nonviolent drug offenders before he left office. Now that U.S. Attorney General Jeff Sessions has kickstarted the drug war again, the chances of two drug dealers walking out of prison in their mother’s lifetime are slim. The federal government claims the pair sold more than 280 kilograms of cocaine, used mostly for crack, and at least 100 pounds of marijuana. (Eddie says he was moving 300 kilos of cocaine a month.)

In prison emails, Eddie weaves a conspiracy involving a disgraced DEA agent, a dirty informant and an autographed Dallas Cowboys football. He claims the government gave him two life sentences because of a 5-kilo deal he took no part in, but he says he just happened to be at an apartment the evening of Jan. 19, 1995, to deliver the football in a shopping bag for a friend when the deal was going down.

“They got me on this because of who I am and not by the evidence,” he wrote in an email. “People can say they see me doing drugs, but the truth is I have never done a thing in my life. They can say I had kids all over town, but I don't. Just cause someone says it don't make it true.”

'Hell on wheels'

Eddie Sotelo slowly approached the house off 25th Street in Fort Worth, holding dynamite that he had tied together. It was the winter of 1978, and his father had told him to tie it to the muffler of a yellow Camaro parked in the driveway. The man who lived there had conspired with a friend to steal heroin that Eddie had delivered for his father. The friend had appeared with gun in hand and taken the dope. Eddie says he couldn’t take his eyes off the gun. It was the first time one had ever been pointed at him. He was 12 years old.He’d stolen the dynamite from the Rock Island train station not far from his father’s house. Rail workers used small packs of dynamite called railroad torpedoes to warn trains in case of an emergency. They’d strap a 2-by-2-inch pack on the train tracks, Eddie says. As the train rolled over it, the dynamite would detonate, making a loud enough bang for a train conductor to hear the noise over the train and know to come to a stop.

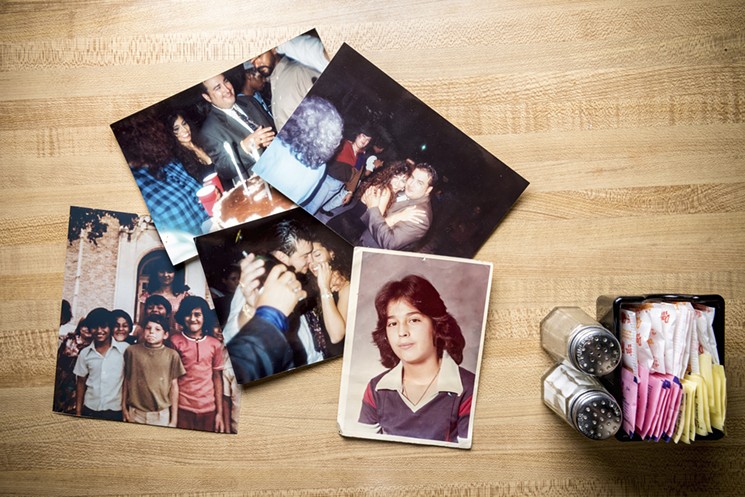

The Sotelos had traveled from Mexico and moved to various parts of Fort Worth before they settled in the Rock Island neighborhood in the 1950s. His mother worked at a factory, and his father, Joe Sotelo, was a womanizer known as “James Dean” and later recalled as the “Brad Pitt of Rock Island.”

The elder Sotelo was known as a classy dresser in his starched jeans, monogrammed shirts and Stacy shoes. He met Mary, a small, dark-haired woman whose eyes sparkle when she laughs, in the 1950s when she was working at Woolworth's. They married in 1959.“My dad was a drug dealer. We did not have regular people coming by. My dad had not many friends. He did not socialize at all. Everyone who went by [his house] was dealin’.” – Eddie Sotelo

tweet this

“My God, that was the biggest mistake,” she says. “He was hell on wheels.”

Joe had jobs as a sheet metal worker, railroad track man and general laborer over the years, but he spent most of his time running the streets and chasing women while Mary raised their six kids and worked at a factory. They divorced in 1976, a year before he was released from federal prison for the first of his two convictions for distributing heroin. Joe had a lengthy rap sheet dating to 1957 and a prior conviction in 1967 for assault with intent to murder. He was sentenced to 10 years in prison in Leavenworth, Kansas, on the drug charge but earned parole in 1977. When he got out of prison, he found a way to pay his ex-wife’s rent of $67 per month and the rest of the bills.

“Where he made his money or how he made it, I don’t know,” his ex-wife says.

Eddie lived with his father in the house on Bluff Street. His mother and sisters had moved into apartments in Haltom City and later Arlington.

“My dad was a drug dealer,” he says. “We did not have regular people coming by. My dad had not many friends. He did not socialize at all. Everyone who went by [his house] was dealin’.”

'I took care of that'

Eddie often went with his father to Mexico to pick up heroin in the late ’70s. He was the only one his father could trust since his older brother Baby Joe, 17, had been sent to state prison in ’77 on several convictions of aggravated robbery with a deadly weapon. He had held up some Safeway and Buddies supermarkets and shot a 16-year-old male employee in the chest for a $200 take. He pleaded guilty to five offenses.A few years later, Baby Joe was paroled, but he returned to prison in 1987 for theft of property and aggravated assault with a deadly weapon after he struck the mother of his child in the face with a sawed-off shotgun.

He paroled out in October 1988, but his parole was revoked in late July 1991 after another charge of aggravated assault with a deadly weapon. He got upset at a girlfriend who ended their relationship and fired three shots into her home from the driveway.

Eddie wasn’t as violent as Baby Joe, who used to terrorize the Rock Island neighborhood, stealing bicycles and breaking windows. Eddie was the good child, more than willing to help his father, who had just gotten out of federal prison when Baby Joe was locked up in ’77. His father had given him a gun to carry and taught him how to cut up heroin to package and sell. When people came to their house on East Bluff Street, Eddie’s job was to wait until he was called into the kitchen to get the money. He would then go out the window, jump over the fence and take the money to a stash house down the street to get the heroin.

“We would never leave the money in the house, ever,” he says.

In the late ’70s, only two main drug dealers were selling heroin in Fort Worth: his father and another man Eddie wouldn’t name. Eddie and his father would cross the border in Laredo and bring the heroin back across in car tires or an oil can. They were buying pure heroin for $3,500 per ounce, which would break down into 11 ounces of powder when it was cut. Each ounce of the cut powder would sell for $2,200, garnering $24,200 in sales.

“That is why the business was so big,” he says.

"I want you to start shooting if I cut the light out. You shoot. I’m going to be on the ground, boy, so you just shoot at the door." – Joe Sotelo

tweet this

It’s part of the reason why Eddie’s father loaded his son up with dynamite after his buyer ripped him off.

“Eddie, I’m going in the house to get my money,” his father said as he pulled up to the buyer’s house. “I want you to stay in the car and watch the front door until I come out. I want you to start shooting if I cut the light out. You shoot. I’m going to be on the ground, boy, so you just shoot at the door.

“If I don’t cut the light off,” he added, “and you see me walking out, then I got my money and you drive us home.”

Minutes stretched into what seemed like hours before his father walked out of the house. He got in the passenger side and told his 12-year-old son to drive.

“I took care of that, son,” he said. “This man was in on the robbery. He knew what he was doing.”

“I didn’t say anything,” Eddie says. “I just was in shock.”

He also didn’t drive very far. His father told him to stop and park the car about a block away from a house on the north side of Fort Worth. Then his father turned to him and said, “I want you to walk up to the house, son. I want you to put this dynamite pack underneath the car. Tie it on the muffler.”

Eddie took the dynamite and slipped through the shadows around the block. He crawled underneath the Camaro, but instead of putting it on the muffler, he placed it in the motor.

“We drove back by the same house the next day,” he later recalls. “The car was all burned up, and the people had moved out.”

'What I was taught'

Eddie pulled up to the Peppermint Motel on the corner of 28th Street and Decatur Avenue in the middle of an afternoon in the mid-’80s to meet the man who controlled the city’s heroin trade. He was an older black man whom Eddie called “the biggest fish in the city” because, in the early ’80s, he took the Sotelos’ heroin and distributed it to everyone else.Big Fish had known Eddie since he was 11 years old. Eddie, now a teenager, was running his father’s business after his father was sent to prison in 1983 for his second federal drug trafficking charge.

“I know all the men he knew,” Eddie says. “They knew I was a smart kid who listens and knows everyone they dealt with. My dad didn’t have to tell me. If I wanted to help my mom, sisters, brother and dad, I knew what to do to get money.”

As he parked, Eddie noticed that Big Fish wasn’t alone in the office. He had a white man with him. “I didn’t trust his friend,” he says. “I had never sold or dealt with anyone white. Only blacks.”

Eddie wouldn’t get out of the truck. So Big Fish walked up to the window and told him that he wanted to buy 6 ounces of heroin. Each ounce cost about $8,500 at the time, but Eddie wasn’t sure if he could get that much and told him that he’d have to see.

He ended up bringing back 2 ounces, followed by 3 more later that afternoon.

Big Fish motioned to his friend, who remained in the office. “Eddie, this man is the money. He can buy all you can get. He is my partner, and he has big money. He wants to meet you and talk to you and do some business.”

Big Fish tried to get Eddie to meet his partner for months, but Eddie wouldn’t do it. Then one day, Eddie went to pick up money for heroin, and the white partner and Big Fish were waiting outside of the office.

“Eddie, we are buying a lot of dope from you,” Big Fish’s partner said. “We want a better price.”

“I can’t do nothing unless I ask,” Eddie replied.

“Come on, talk to your people. Get them to lower the price for you. We are buying over $50,000 a week now.”

“I can’t, and I won’t,” Eddie said. “You pay this price or not. I don’t care.”

Eddie left the motel and received many pages on his beeper. He didn’t answer for four days. When he responded, they agreed to pay the $8,500. He says he felt sorry for them and agreed to cut them a deal for $8,300 per ounce. When he returned to pick up the money, they broached the subject again.

“Hey Eddie, you ever mess with cocaine?” Big Fish’s partner asked.

Eddie shook his head.

“Take a look at this.” Big Fish’s partner pulled out a kilogram of cocaine and threw the package to Eddie. At that time in the ’80s, cocaine was coming out of the Miami area.

Eddie looked at Big Fish. “Man, I can’t sell this. I don’t know anyone to sell it to.”

“Eddie, you know everyone,” Big Fish replied. “I’m sure you can sell it. Just try it out and see. Maybe we can trade it for some heroin?”

“I didn’t even want to ask my people to do that at all,” Eddie later recalls. “Hell, I wasn’t that damn smart, and I wasn’t eager to do this. I was only doing what I was taught [to survive].”

They told him to take the cocaine and see if he could turn it. They wanted $38,000 for the kilogram and said that he could either make payments or give them a better deal on the heroin.

He stashed the cocaine behind the motel and told one of his friends to get his bicycle and ride back to the motel to pick it up. They broke it down into 1-ounce sacks and sold it all in three days. Eddie took the money back to the Peppermint Motel, and the men wanted to give him more cocaine to sell.

As the ’80s slowly crept toward the ’90s, cocaine quickly spread through the black and Hispanic communities around the country in the form of crack. Eddie had been introduced to it when it was relatively unknown and quickly ascended to a position of power as if he were Tony Montana from Scarface — but without the machine guns; a 9 mm pistol was his weapon of choice.

'Where's the stuff at?'

Eddie followed Lawrence “Chubby” Flores into the apartment in the 4500 block of Nautilus Circle northwest of the stockyards in Fort Worth, unaware that DEA Special Agent Will Travis had set up the drug deal that was about to transpire. It was shortly after 5 p.m. on a Thursday in late January 1995, and the Sotelo organization, now controlled by Eddie, had cornered the market on cocaine, setting up deals all over Fort Worth, Dallas and Houston.After the Peppermint Motel days in the mid ’80s, Eddie hooked up with Henry Arguijo, who, the federal government claims, became his major cocaine distributor from at least 1988 until about 1992, when the Sotelo organization took over the market.

“Once the DEA seen it was me on site, that is when the wheels started turning to get me off the streets.” – Eddie Sotelo

tweet this

At the time, the Sotelo organization comprised mostly Eddie’s Rock Island neighborhood friends. Baby Joe delivered cocaine and acted as an enforcer when he wasn’t serving time in prison. They also brought on board Gary Artiaga, who’s known the Sotelos since high school, and Ernest “Ernie” Quintana, who, the federal government claims, acted more like an errand boy, similar to Eddie’s friend Chubby. Law enforcement officials identified approximately 22 individuals with some connection to the Sotelo organization.

The Sotelo organization was dealing large amounts of cocaine to people who seemed to be reliable until they turned on Eddie in federal court in 1995 in hopes of transferring their cases to a state court where they could serve less time.

The money seemed to be flowing, too. Eddie opened a swank disco nightclub called the Polo Club near the historic Billy Bob’s in the stockyards. Eddie had become his father. He dressed in flashy clothes and drove Hummers and other fancy cars. He and his friends took vacations to exotic locations and attended the Super Bowl when the Dallas Cowboys reigned supreme on the field.

Eddie had a couple of run-ins with the law over the years. In the early ’90s, he was incarcerated for nearly three months on a theft charge, and he returned to jail for a couple of months in ’92 on a parole revocation. Then the Fort Worth police investigated the abduction of a local 15-year-old named Gilberto Robles, who was kidnapped on June 19, 1993, after his older brother Juan duped the Sotelo brothers out of $18,000 when he gave Baby Joe a kilogram of flour instead of cocaine. Eddie and Baby Joe were never charged with kidnapping.

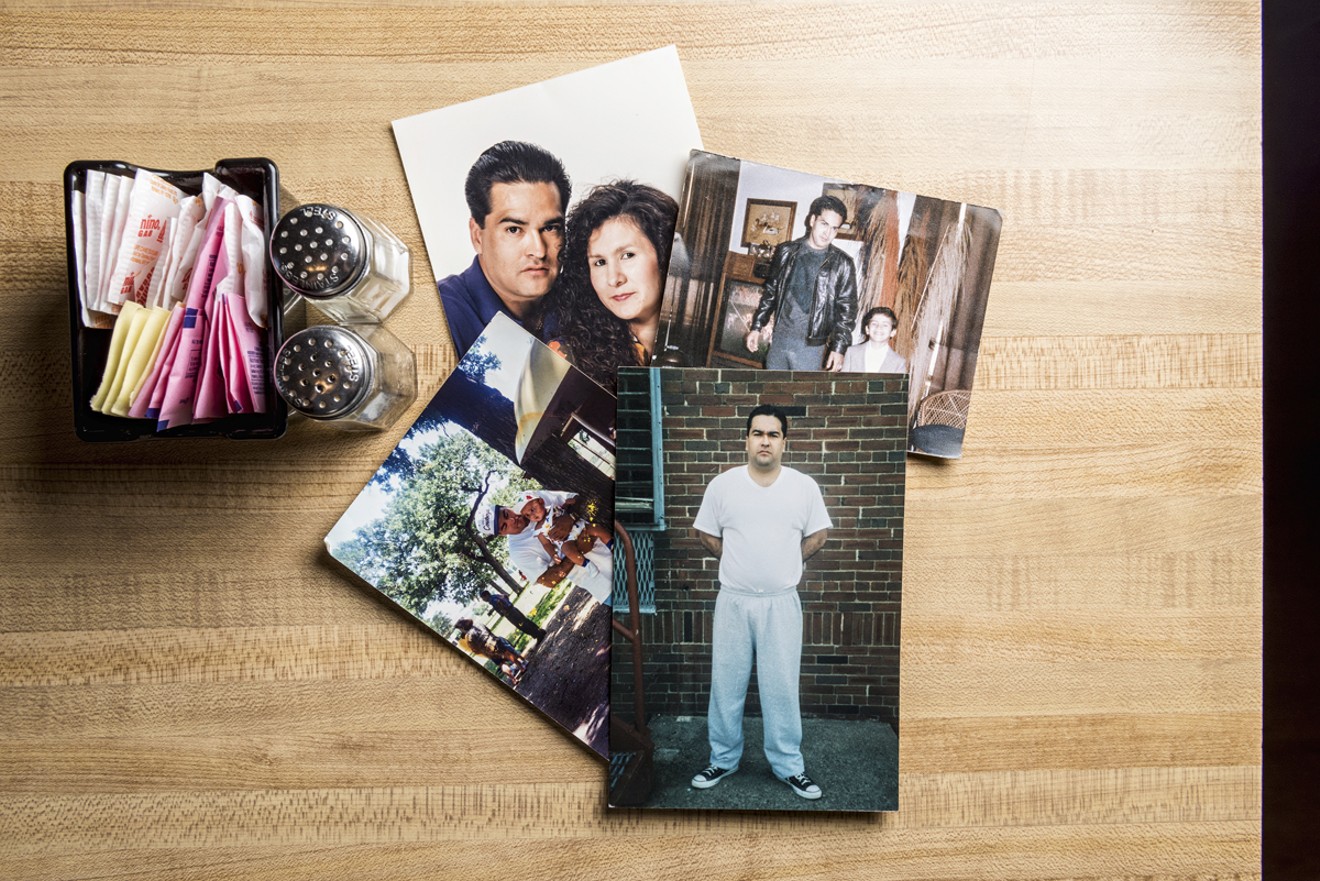

When he walked into the apartment on Nautilus Circle in late January 1995, Eddie should have known law enforcement was hot on his trail. The Fort Worth Police Department's gang and narcotics units and the FBI had executed a search warrant the previous year and arrested Eddie at his home. They found a small amount of cocaine, $74,117 in cash, a loaded Taurus 9 mm, drug distribution notes and photographs that seemed to capture the fruits of his labors: Eddie standing with various friends, fanning large amounts of cash, sometimes in front of a Learjet.

Eddie posted the $25,000 bond in July ’94, but he didn’t stop dealing. A month later, he met Kevin Blevins, a small-time drug dealer, at a Quick Wash laundromat near the corner of McCart Avenue and Alta Mesa Boulevard and noticed Blevins had brought someone with him. Eddie was sitting next to Ernie in a car that belonged to his sister, Melissa Sotelo, when the man — an undercover cop — got out of Blevins’ car and approached. The officer noticed a large black baseball equipment bag lying across Eddie’s and Ernie’s laps in the front seat.

“Man, I don’t know you,” Eddie said and began slowly backing up his car. He looked at Blevins. “I’ve got your stuff. You come with us and leave him.”

The cop gave the signal, and a police surveillance team appeared and tried to box in Eddie’s car. Instead, Eddie struck one police unit and then another as he made his escape. As he sped away, he threw out the bag. The police found it loaded with 10 pounds of marijuana and 1,000 grams of cocaine inside. Eddie later told one of his buyers, who eventually testified against him in federal court after his own drug bust, that he had spent the night hiding in the bushes.

Although they had failed to capture him then, law enforcement officials were ready to try again at the apartment in January 1995. Travis, the DEA agent, used a 24-year-old confidential informant named Arthur Franklin, a known cocaine distributor, to set up a 7-kilo buy with Jesus “Jesse” Juarez, a friend of Eddie's. If he could catch Eddie with 5 or more kilos, the federal government would be able to seek the maximum penalty and keep him off the streets for the rest of his life.

A young DEA agent looking to make his mark, Travis had arrested Franklin in October 1994 at his mother’s house in the Crowley neighborhood in Fort Worth. He’d been caught with cocaine and several thousand dollars. Travis worked out a deal for Franklin to work off his charges if he helped turn over his connections. Franklin turned over his Colombian connection in Houston and a buyer in Wichita Falls before he gave up the Sotelo organization.

On the evening of Jan. 19, 1995, Franklin entered Juarez’s apartment shortly after Eddie and Chubby arrived. They were sitting on the couch waiting for him. They had no idea that several DEA agents and a task force agent named David Priest were conducting surveillance.

“Where’s the stuff at?” Franklin asked.

Eddie snapped his fingers and Chubby got up, went downstairs to the car, grabbed a shopping bag and brought it back to the apartment. Eddie asked Juarez for a knife and cut the package open to show Franklin that it was dope. It's unclear why only 5 kilos were present instead of the requested 7.

“It’s good for cooking [crack],” Eddie told him.

Franklin looked at Juarez. “Let me speak to you outside.”

As soon as they stepped outside, Franklin tried to use the cellphone that Travis had given him, but its battery was dead. He told Juarez that he was trying to get in touch with “one of his broads” who had the money for the kilos. “I didn’t want you to see the money because it could have been a jack move,” he said.

When he realized the phone wouldn’t work, Franklin took off his jacket, a prearranged signal with the DEA agents watching the apartment. They arrested Eddie and Juarez in the apartment parking lot and Chubby in the apartment. A special agent reported finding 5 kilos of cocaine in the shopping bag that Chubby had carried into the apartment.

Franklin was arrested again shortly after testifying in the Sotelo trial for allegedly selling 3 kilos of cocaine to a Fort Worth jailer in Memphis, Tennessee. He bonded out of jail and was found murdered a couple of months after the Sotelo brothers were convicted. The murder was never solved.

“I was at Jesse’s apartment dropping off an autographed [Dallas Cowboys] football to him for a friend we both know,” Eddie wrote in an Aug. 16, 2016, email. “Once the DEA seen it was me on site, that is when the wheels started turning to get me off the streets.”

The wheels had actually started turning long before his arrest.

'He does not deserve to die in prison'

The Sotelo matriarch, Mary, sits next to her daughter Patsy in early May in the bar that was once the family living room. Like the rest of the family, she wants to see her sons released from prison, but she’d also be happy if the federal prison bureau would simply move her youngest son, Eddie, closer to home. At 79, she can no longer make the trip to the federal prison in Pennsylvania as often as she’d like. She only has to travel four hours to see her oldest son, Baby Joe, in El Reno, Oklahoma.“It was because their dad was a bad example,” she says. “I blame him for everything. Of course they made choices. They made choices to make easy money. They didn't make choices like Mom to go to work and make a dollar and 10 cents an hour. But at least you're not worried about someone putting you in jail.”

Twenty-two years have passed since the Sotelo brothers and their seven co-conspirators in the Sotelo organization were taken off the streets. They were found guilty of their crimes in a federal courtroom in Fort Worth, but nearly everyone involved has since served the time and returned home.

Some of them drop by the family restaurant. Chubby Flores still acts as a family helper. Instead of dealing drugs, he watches the kids from time to time. Gary Artiaga claims he’s now a successful businessman. Henry Arguijo helps Eddie’s older sister Patsy with the restaurant. She calls him her “angel” because he’s the silent partner who gave her the money to open the restaurant. He runs a successful business in Fort Worth manufacturing tarps for trucks.

But Eddie and Baby Joe remain in the federal penitentiary system, serving life sentences a thousand miles apart. Eddie plans a long-shot appeal to introduce new evidence to get rid of his life sentences. Among other things, he claims that Juarez took the rap for drugs, but the jury didn't know about it during Eddie's sentencing.

Eddie's older sister Patsy still struggles to accept that her brothers remain behind bars because, as she points out on several occasions, people change, like the co-conspirators who she says are now upstanding citizens. Patsy is also following the straight and narrow, much like her older sister Linda, whose rap sheet includes forgery, credit card abuse, bail jumping, engaging in organized criminal activity, fraud, possession of a controlled substance and tampering with government record. Patsy dabbled in aggravated armed robbery, credit card abuse and theft. She was known as the "Tom Thumb robber" because she had held up several Tom Thumb supermarkets in the Fort Worth area.

“Back in the day, I was totally irresponsible, young and partying, and just thinking that I could do whatever the hell I wanted to do,” Patsy says.

Patsy's younger sister Lisa followed in her brother Eddie's footsteps. She's serving 27 years in a federal prison for a drug charge.

Patsy put together a pink folder filled with Eddie’s accomplishments in prison, including certificates for completing courses like The Power of Consequences; Tactics, Habits That Block Change; and Commitment to Change, Good Intentions, Bad Choices.”

Eddie was sentenced to life in prison 79 days after his father was released from prison in late 1994. “Never in my life did me, my brother Joe and my dad ever spend more than 79 days together,” he says. They don’t even have a family photograph together. His father died in 2005.

But Eddie hasn’t just spent his time in prison learning to make better choices or the history of rock ‘n’ roll, which he also received a certificate for. He was also helping Manuel Reyes, a cold case detective for the Fort Worth police, solve old murder cases. Reyes wrote prison officials in April 2011, requesting that Eddie be transferred to a lower-security prison. “Mr. Sotelo has provided substantial information to the City of Ft. Worth Police Department and other cities’ police departments, and continues to do so of this date,” Reyes claimed.“It was because their dad was a bad example. I blame him for everything. Of course they made choices. They made choices to make easy money." – Mary Sotelo

tweet this

Eddie says he has served his time in 11 prisons since 1995, but he remains in a maximum-security federal prison despite his help. Prison records show that he has never been part of a gang, and he claims to have saved eight inmates' lives.

“I almost gave up a few times on myself doing a relatively short sentence,” former inmate Ray Zapata says. “It amazes me how a man with three life [sentences] can be so strong. Please know that he is a good man. Prison makes people ugly. It has not broke him. He does not deserve to die in prison.”

At the restaurant that Sunday afternoon in late May, members of the Sotelo family claim that local police still hassle them sometimes. And their last name still appears in crime news articles from time to time. But many of them point out that they are just hardworking people trying to change the public’s perception.

Other law enforcement officials still make appearances at the East Bluff Street location but only to enjoy the family’s home-cooked meals. Patsy says the DEA agent who busted her younger sister Lisa even made an appearance to try her food.

“President Obama was saying that anyone with a drug conviction where you spent more than 20 years or your life … it’s too much, you know?” she says. “My brothers have been punished enough. They need the opportunity to show that they will do as well as the other guys and not reoffend.”