Now the statue is locked up in some purgatorial storage facility where, at least theoretically, it probably could be left forever, once people’s memories have faded. It stood on a hill in Lee Park (temporarily renamed Oak Lawn Park) on Turtle Creek for more than 80 years while relatively few people knew or cared what it was.

But that seems wrong and weasel-like, given the passions expressed during our long municipal debate on whether to tear it down and the even longer, more agonizing process of actually getting the job done. The continued existence and ultimate fate of the Lee statue is something we ought to be able to button down one way or the other, for history’s sake. So here is my idea.

The people who feel strongly that the Lee statue should be placed back into a position of veneration in our city need to stand up, declare themselves and be counted. They should call a press conference, stand in front of the cameras and hand out cards to make sure their names get spelled correctly.

One of the problems with the way Lee was displayed in Lee Park all those years was the issue I mentioned above — people not knowing what the statue was supposed to represent. Lee Park is a lovely place, but like so many Dallas references to the Confederacy, Lee Park and the Lee monument were shrouded in a lot of polite misdirection verging on camouflage, a kind of covert cultural signaling, as if the people who needed to know why he was there on his horse would know without being told and the people who didn’t know didn’t need to.

So let’s get that all out on the table with the lights on. The people who want to see the Lee statue put back on honored display need to put themselves on display and allow the rest of us to get a good look at them.The topic of the Civil War and slavery has been draped in layers of euphemism, bordering almost on mysticism, as if somebody really does not want to get down to the brass tacks of things.

tweet this

One of the more frequent suggestions during this process has been that the statue be placed in a museum, which, in Dallas, sometimes means it should be put in a place where no one will ever go. But to the extent putting it in a museum is a real idea, the champions and defenders of it should take on the task.

They need to put together some kind of a presentation and make their pitch to every museum in the city where they think the Lee statue could be suitably housed and displayed. For the sake of our municipal soul, those meetings should be public. Maybe there could be a kind of process put in place, like a Lee statue installation tribunal.

Each museum could be summoned to appear. The pitch would be made. And each museum would explain its position, yea or nay. I cannot imagine a more valuable educational experience.

Another idea suggested more than once during the removal debate was that some wealthy private person might want to acquire the statue. But the statue has never been private before. It did not come into the world privately. Its career in Lee Park was not private. Its removal was not private. Shunting it off out of the way to some private hiding place seems cowardly and irresponsible.

What about this instead? What if the champions of the Lee statue were able to persuade a private person to acquire it and visibly display it on private property, so that it could be viewed, at least, from a passing car?

And what purpose would that serve? Am I just trying to embarrass somebody or be a smart aleck? I don’t think so. From the end of the Civil War up through the era of the 1939 movie Gone with the Wind and even into the present, the topic of the Civil War and slavery has been draped in layers of euphemism, bordering almost on mysticism, as if somebody really does not want to get down to the brass tacks of things.

The figure on horseback is so dashing, so heroic. What would it take to provide it with a historically accurate balance?

Patrick Williams

Another frequently suggested solution to the problem is that the statue could be rendered nontoxic by displaying it “in the proper context,” surrounded by other works that would provide historical balance. That strikes me as the most difficult of all the suggestions to achieve. Balance would be far more difficult to achieve than context.

The context is easy. There was a war. He was a general on one side. His side lost. There you have it.

The balance, on the other hand, would be wickedly difficult. Against Lee’s floridly romantic figure high atop a horse leading the way forward for Dixie, what image would set the proper moral and historical balance?

I know of one I can’t get out of my mind since coming across it several times in the documentary history of slavery. It’s in Solomon Northup’s contemporary journal 12 years a Slave, and it appears repeatedly in the oral history interviews with the last living former slaves carried out by the Works Progress Administration in the 1930s.

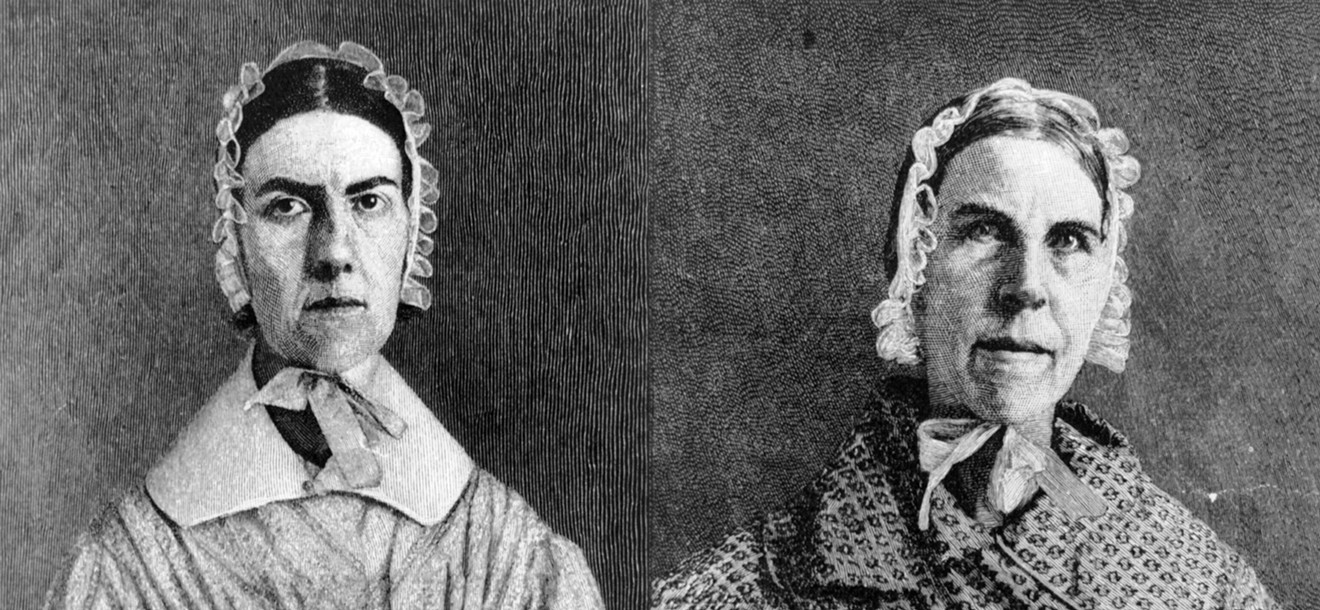

I am speaking of the stories of white women slave-owners, usually wives of planters, who whipped black children to death in front of their mothers. This level of depravity, brought about in white people by the act of slave-owning, inspired the Grimké sisters of Charleston, South Carolina, white daughters of a wealthy planter, to become the first American female advocates of abolition and women’s rights. Sarah Moore Grimké and Angelina Emily Grimké campaigned for abolition primarily because of what they saw slavery do to the white soul.

So fine. If we’re going to put Lee back on display but in a proper context, then we need to talk about a new nearby statue depicting a white woman flogging a black child to death while the child’s mother looks on. Or maybe a better historian can come up with an even more evocative way to get the message across.

The challenge in achieving balance will be finding something with sufficient weight and power to pull the heroic figure on horseback back down into the real mud and blood of the matter. I’m not saying it can’t be done. I’m not going to do it because I’m busy. But the people who say they want the Lee statue to find a final public or semipublic resting place might be able to pull it off. They just need to get busy, and the first thing they need to do is stand up and be counted.