Jakes told Schnurman, “So many problems we have — whether we want to admit it or not — come back to the lack of opportunity. There’s a feeling of hopelessness and despair that exists in the underserved areas.”“If I can just get the people in the room, even if they start by driving a truck. You can’t climb the ladder if you’re not near the steps.” — T.D. Jakes

tweet this

That’s almost all true, and Jakes is a hero for saying it and for taking it on as a mission. It’s all about work. The conundrum of work and not working lies at the heart of the tragedy of southern Dallas. But that puzzle gets deeper and trickier than the mere question of opportunity.

Say this much: It’s not going to be a white man who figures this out. Not here, not now, not for a while. So Jakes, who is black, is stepping in right where he is most needed and can do the most good.

Back in 2013 when the city was devoting all kinds of public resources to the creation of an exclusive, hyper-expensive private golf course in southern Dallas, I took a deep dive into the employment numbers for the census tracts surrounding the site. Unemployment was significantly higher than rates north of there in the whiter part of the city, but that was not the number that jumped out at me.

The really striking statistic was for something the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics calls “not in the labor force.” The BLS defines persons not in the labor force as “retired persons, students, those taking care of children or other family members, and others who are neither working nor seeking work.”

The numbers for the census tracts near the golden golf course showed a staggering 60% of the population categorized as not in the labor force. That’s twice the ratio of typical tracts in the white half of the city.

The last part of the definition, “neither working nor seeking work,” includes a category called “discouraged workers.” Technically those are people who have given up on finding work, but the definition probably should be expanded to include people who never had the slightest hope or expectation of finding work in the first place. I’m sure we could all agree on that amendment without too much battle.

But the definition of “not in the labor force” also needs to include another category or description that causes everybody to draw knives whenever the words are uttered — people who don’t want to work. And I would refine even that, based on personal experience, to something more like people who don’t want to work at the kind of jobs available to them.

On what personal experience would I base a thing like that? On my being a white asshole? Well, I can accept some of that. My siblings didn’t address me as white, but I may remember the rest of the phrase as being sort of a nickname around the house.

But, listen, I’ve also dealt with the issue of work and not working in Dallas over a period of years. I believe I do know what I’m talking about when I say Jakes’ message is a major departure from what some influential black leaders have spoken to their constituents in the past.

Jakes told Schnurman: “If I can just get the people in the room, even if they start by driving a truck. You can’t climb the ladder if you’re not near the steps.”

That is literally the opposite of what Dallas County Commissioner John Wiley Price was telling his constituents a dozen years ago. Price then was throwing his considerable weight behind a successful campaign to shut down a California entrepreneur who wanted to develop a major new shipping and warehousing center in Price’s district.

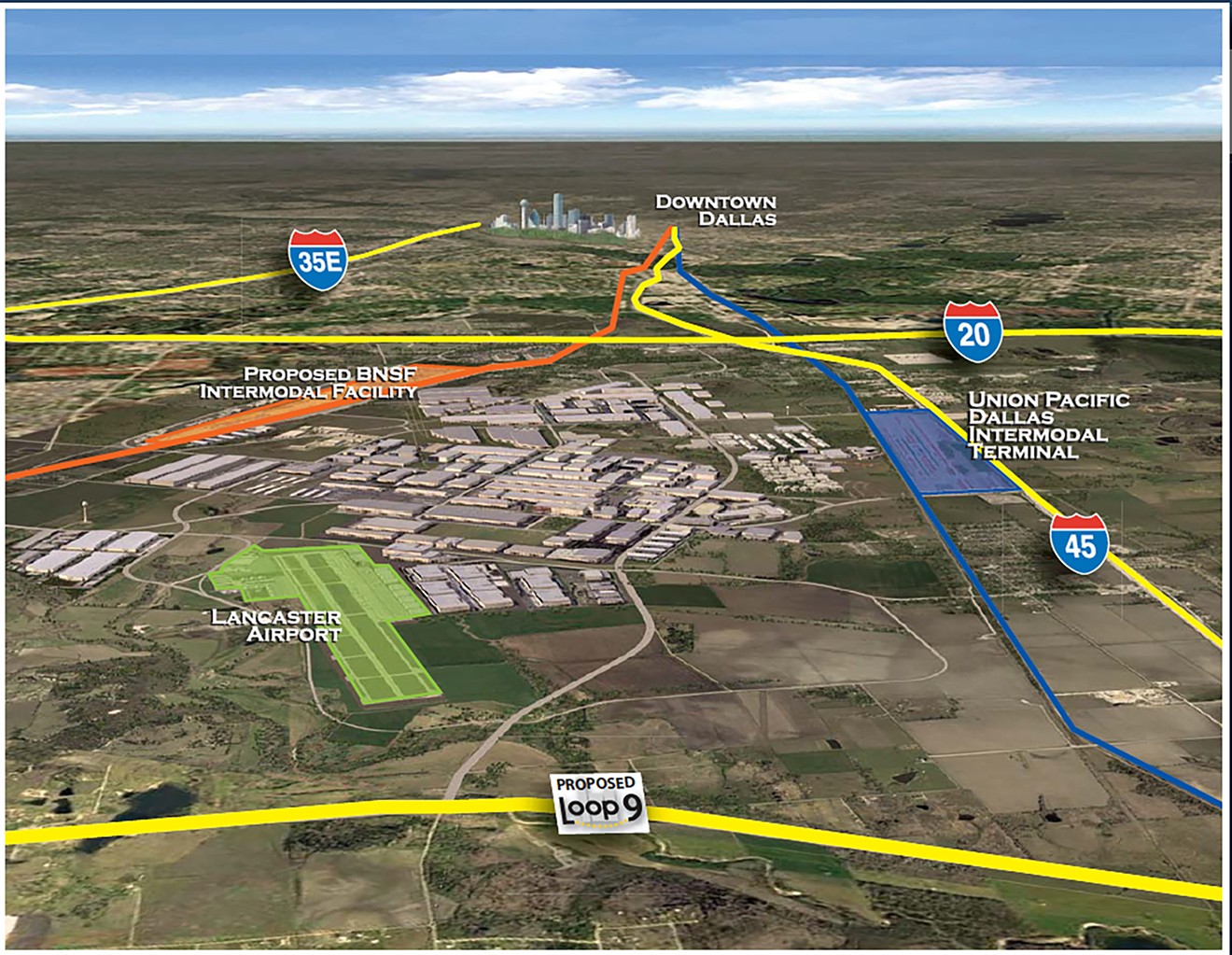

Richard Allen, a respected player nationally in the logistics industry (warehousing and shipping), had amassed 6,000 acres of land in southern Dallas and proposed a development that he said would bring 60,000 good, new jobs to Price’s district. But Allen’s project would have competed directly with a similar operation in Fort Worth owned by Dallas’ influential (and white) Perot family.

The Dallas Morning News campaigned against the southern Dallas project in both its editorial and news columns. Later in court testimony, executives representing the Perot interests testified that they had viewed the southern Dallas project as a serious potential competitor.

Price, who had ties to the Perots through his campaign adviser, Kathy Nealy, joined the effort to kill the Allen project, but he never said publicly he was opposing it because of his ties to the Perots. On southern Dallas radio, in personal appearances and in written statements, Price said he opposed the project because the hourly labor jobs it offered — all 60,000 of them — were an insulting link with slavery.

Dallas County Commissioner John Wiley Price, a revered leader for a third of a century in his southern Dallas district, has disdained hourly wage jobs as a legacy of slavery.

Brandon Thibodeaux

He meant it. He had other agendas, of course, but he meant what he said about slavery and jobs. I argued with him about it on the phone. I said, “During slavery nobody had a job.”

He said, “They did have a job. What was it called then?”

“It's called slavery," I said. “They stole their lives.”

“Slavery, Jim, that's an institution. And the effort of the institution was working. And working traditionally is a job. I am going to tell you, the nickname that most African Americans have for a job. It's called a slave.”

Those were terrible words from a leader who enjoyed enormous respect, power and influence in his domain. He wasn’t just saying it to me, the white asshole. He was on the radio, in churches and on the stump saying the same things to his own constituents.

It would be absurd to believe or suggest that Commissioner Price’s words went without powerful impact on the people who heard and read them. For 36 years he has been reelected by overwhelming majorities to the District 3 county commissioners court seat covering a third of Southern Dallas and all of the far southern and southeastern portions of the county outside the city limits. As the city’s longest serving and most powerful black officeholder, Price’s influence extends far beyond the boundaries of his own district."I am going to tell you, the nickname that most African Americans have for a job. It's called a slave.” — John Wiley Price

tweet this

He was acquitted three years ago of federal corruption charges in a high-profile trial, during which a lot of the Perot story was in evidence. It would be easy to dismiss his line on work and slavery as a cover-story. And it would be a huge mistake.

Price grew up in the town of Forney east of Dallas when it was still a dusty cotton town. In that part of Texas, a form of slavery-like indenture called debt-peonage persisted well into the 20th century, according to the Texas State Historical Association and other researchers.

During the fall harvest when Price was a high school student in Forney in the early 1960s, black students were dismissed from their segregated public schools to work in the fields. White students stayed in class and studied.

Price told me once that when he looked out across the endless rows of cotton and saw only black faces and black hands bent to the cotton, black backs dragging the long sacks, while the white kids were all back in school with their noses in their books, it sure as hell looked like slavery. The point I took away with me was that the shadow of slavery was much more recent here for poor rural and small-town African Americans than a white asshole from Detroit might imagine.

So when we come to this issue of working, of taking hard jobs and maybe even dirty jobs to earn one’s way into the mainstream economy, we do not come with clean hands. Not me, anyway. Maybe not you, depending on what color you are.

For one thing, the insult and injury of slavery never stopped, even if slavery was ended as an institution. Layered on top of the original horror of slavery was a century and a half of Jim Crow, slammed doors, humiliation and overwhelming rejection.

Sure, the very strongest black families bowed up their backs and marched straight into it, fiercely determined. But what percentage of us all are the very strongest? How many white people are the very strongest?

In fact, when we look at the fierce refusal and rejection inflicted on black job-seekers for a century and a half, that description of “discouraged workers” feels tame. Words closer to despair, bitterness and even agony seem more appropriate.

Don’t get me wrong. I don’t agree with Price one bit. I come from bootstrap immigrant roots. I have to always viewed the real promise and glamour of America as a chance to find an abandoned broken-down wheelbarrow so you can haul dead dogs to the rendering plant for pennies until you can afford a good wheelbarrow and pick up scrap metal for dimes. That’s how the dream begins, with work.

I think I get why Price said all those things. But I also believe Jakes is right. A life without work is a ticket to hell on earth. And that’s not just a guess. For a quarter-century a solid body of research has found that unemployment is much more closely tied to crime rates than poverty.

In the late 19th century, the pioneering French sociologist Emile Durkheim proposed a link between obsolete trade guilds and a condition he called anomie — a kind of disconnectedness, a profound sense of not belonging, which Durkheim later tied to suicide. I have wondered if suicide may not be a cousin to casual murder, a sense that none of it counts for anything anyway.

Jakes puts it all much more directly: “If you have to go to work in the morning, you’re not hanging out on the streets at night with a gun.”

And he can say it. There is a reality here. What Jakes is saying can only be said from within the black community. I already told you my nickname.