Did what I said about it a month ago even make sense back then? I wrote that taking down Confederate memorials might deprive us of a useful historical context. Whatever that opinion may have been worth when I offered it, it’s inane now.

In the wake of Charlottesville and with a local statue debate about to explode in the City Council chambers, my call for context utterly misses the moment. If this was ever about abstractions, it isn't anymore. What the nation faces in this debate is a white racist battle cry, a direct malevolent challenge to the heart of our democracy. The issue is how we respond to that challenge right here and right now, in this moment.

Dallas Mayor Mike Rawlings issued last week what he felt at the time was an appropriate call for caution and delay. He said he wanted to appoint a commission to study the statue issue. Two black City Council members, Tennell Atkins and Casey Thomas, acting from a long history in Dallas of black accommodation, have withdrawn their support from a call for the council to consider removal and have sided with the mayor for a stall.

Meanwhile, the moment approaches at warp speed. Rawlings surely didn’t recognize that his attempt to tamp down the heat was a very unfortunate echo of efforts by southern mayors in the 1950s and ’60s to dodge the big civil rights moments by stalling and offering half-measures. Whatever Atkins and Thomas think they are accomplishing by allying themselves with those efforts, Dallas has plenty of other respected black leaders who see the moral mistake in delay and temporizing.

The Rev. Gerald Britt of Dallas, who has a long association with the Southern Christian Leadership Conference and is most often an ally of the mayor, took Rawlings to task Friday on the op-ed page of The Dallas Morning News:

“Dallas Mayor Mike Rawlings missed an opportunity this week to stand up for justice and fairness. Our country is in a moral crisis. We cannot look to the White House for leadership. We cannot look to our statehouse for leadership. We only have our city leaders, and while I've been a steady supporter of Mayor Rawlings, this time, he missed the moment.”I’m serious about something here. I’m not citing my own words about the statues a month ago as some kind of false modesty. Believe me, there is nothing false about my modesty right now. I feel stupid. How did I find out I was stupid? This moment in history came along and blew me down like I was a bug in a tornado. I’m still choking on the dust. This is how history teaches us sometimes. So I hope the mayor will find it in his heart to change his mind about delay.

And that brings us to an even more difficult topic as we get ready for our municipal close encounter with history in Dallas. How should we as citizens respond when the Nazis march here?

Any of us — every one of us — can understand the satisfaction that people in the antifa (anti-fascist) movement felt when they donned helmets, picked up shields and went to do battle with the racist demonstrators in Charlottesville. What could be more satisfying than punching a Nazi in the face?

And that’s exactly what’s wrong with it. That’s the moral error right there. Personal satisfaction is the crack cocaine that keeps people from getting straight with history.

History isn’t about me. Or you. It’s universal. That was the powerful, overarching principle recognized by Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. and the national leaders of the Southern Christian Leadership Conference, who, by the way, were all really well versed in history and philosophy.

Maybe there’s a misunderstanding about nonviolent resistance among people who do not know the history of the civil rights movement in general or the SCLC in particular. Maybe somebody thinks there was something soft or easy about nonviolent resistance.Depriving evil of a resort to equivalence is bitterly hard work. Evil’s greatest desire is to pull the opponent down into the muck with it.

tweet this

The SCLC ran boot camps to teach people how not to fight back, how to take a beating and never throw a punch. The point of it was never the fight itself. The point was that when the larger world looked in on what happened in Selma, in Montgomery, in Little Rock, the world saw evil on one side only. One side only was spitting, kicking, beating, burning, killing.

Look at the gift the antifas handed to President Donald Trump at Charlottesville. The moment the first image appeared of anti-Nazis wearing helmets and throwing punches in Emancipation Park, it was an absolute given that Trump or somebody like him would use that image to declare the moral equivalence of the two sides.

Last Saturday night’s vigil for peace in front of Dallas City Hall came out OK, and the leaders who organized it, including some from Black Lives Matter, deserve credit for that. But it could have gone the other way.

The supposedly antifascist “black bloc” people wearing masks that I saw flitting through the crowd Saturday were mirror images of the neo-Nazis — a lot of nerdy-looking, pent-up young males in costumes, trying to look tough, spoiling for a fight but afraid of getting hurt, hence the padding.

Seeing them raised a real question in my mind: Who threw the first punches in Emancipation Park in Charlottesville? Yeah, yeah, Nazis are bad. No kidding. But who threw the first punches in Emancipation Park? History will want to know.

Depriving evil of a resort to equivalence is bitterly hard work. Evil’s greatest desire is to pull the opponent down into the muck with it. It’s so hard not to give in to that.

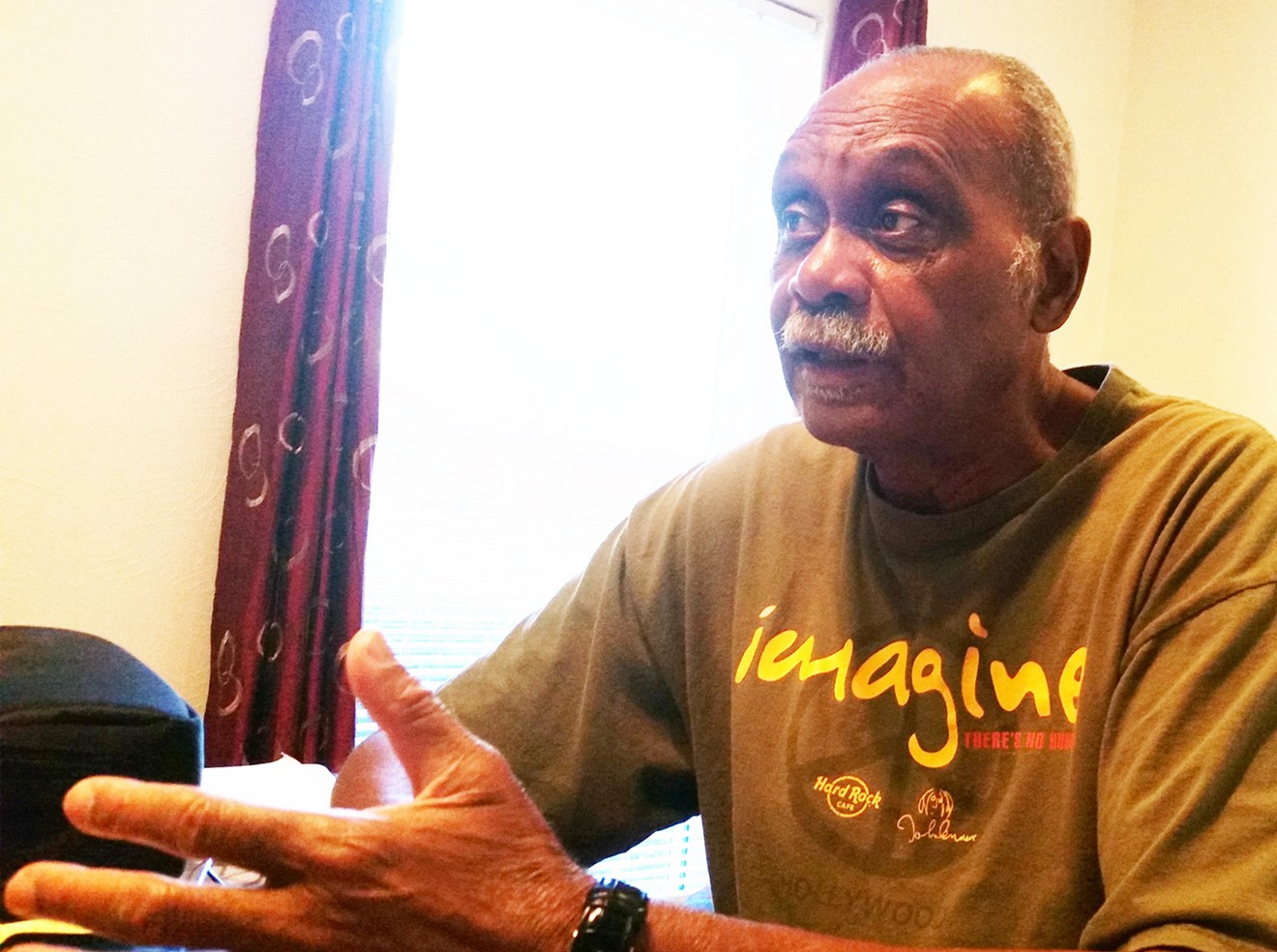

Last week, I spoke with an old friend, the Rev. Peter Johnson, a Dallas black leader who spent most of the movement years in the 1960s at the side of MLK, at first as a young body guard and later as an advance man for the SCLC. He told me a story once about how hard it was to be nonviolent, and I asked him last week to tell me again.

He was 19 years old when this story took place in Selma, Alabama. James Reeb, a white Unitarian Universalist minister from Boston, was walking from a restaurant meeting with MLK and other movement leaders when he was attacked by white men, one of whom struck him a savage blow in the head with a club.

The Edmund Pettus Bridge in Selma, Alabama, was the site of Bloody Sunday — March, 7, 1965 — when Alabama state troopers firing teargas and wielding clubs put 50 civil rights marchers in the hospital. Johnson still suffers from internal injuries he received on the bridge that day.

Rex Wholster

“First of all,” Johnson told me last week, “growing up in the country, everywhere I went, in the trunk of my car was a tackle box with all of my fishing tackle and a shotgun because I grew up hunting and fishing.

“In Selma, Alabama, when James Reeb was beat to death, who was my friend, I went to get my goddamn gun out the trunk of my car, and I was going to kill an Alabama state policeman.” He says he still believes that’s what would have happened “if it hadn’t been for Andy [Andrew Young] and Rev. [Ralph] Abernathy, who knew me well enough to know what kind of fool I was.

“I want you to realize this. James Reeb was bleeding to death in the back of a black hearse because the white ambulances wouldn’t take him. The nurses and the medical people in the back of the hearse tried to stop this man from bleeding from his head.

“The hearse was parked in front of the Catholic church. There was a state police car on one side, right next to it. In front of it was another police car. Behind it was another one. It couldn’t move unless somebody moved.

“Rev. Abernathy was begging them to let that hearse out. I’m 19 years old. I’m standing there on the steps. I’m listening to this shit. Rev. Abernathy said, ‘If you don’t let this man get to the hospital, he’s going to bleed to death.’

“What he [the Alabama state trooper] said was, ‘Let that nigger-lover bleed to death.’ When he said that, I just turned around and went straight to the back of my car and got my shotgun. Chambered a round.”

Johnson says he would have shot the policeman “if [Young and Abernathy] hadn’t seen me, tackled me and wrestled that gun from me. It’s lucky I didn’t shoot one of them [the civil rights leaders], as crazy as I was.”

The lesson he says the movement leaders imparted to him in the days and months that followed was that he didn’t have the right to strike back in anger. It wasn’t his prerogative to find satisfaction in fighting back.

What counted in history was the moral equation. The racists were evil. The civil rights warriors were not. If James Reeb and countless other martyrs had to lie in the backs of ambulances or on the pavement and die in order to keep that equation whole, then they had to die.

“You had to be taught to be nonviolent,” Johnson says. “You had to be taught how to do that.”

Think about it. Think how much harder nonviolence was than punching a Nazi in the face, how much more bravery and selflessness it took.

So as the moment rushes down on us, while I do my own midcourse corrections and mea culpas to keep up and prepare, I hope the people who intend to confront the Nazis will give serious thought to how they’re going to do it. Confronting the Nazis is good. Acting like them is bad. It’s that simple, and it’s that difficult.

Reeb, age 38, died at the hospital.