Michael Ochs/Getty

Audio By Carbonatix

A couple of weeks ago, we looked back on the Rolling Stones’ best deep cuts, prompting us to take a deep dive into their later-career highlights. Naturally, we decided to find the absolute best late-career masterpiece songs of other artists from long after their heydays.

Here are the best late songs by artists who had peaked much earlier.

Bob Dylan, “Not Dark Yet” (1997)

Bob Dylan is the closest we have to an actual messianic figure in music, appearing and disappearing from the public eye as he sees fit. While he enjoyed a brief resurgence of popularity in the late ’80s with his hit “Everything Is Broken,” he didn’t release any original material for almost a decade through the ’90s, leading many to count him out creatively. This is exactly when he made one of the best records of his career.

In 1997, Dylan released Time Out of Mind, reteaming him with producer Daniel Lanois, who helmed “Everything is Broken.” At 56, Dylan’s mortality had become more and more of a concern throughout his songs. He chillingly embodies the lingering feelings of a breakup on the opening track “Lovesick,” evoking the dry agony more than any young musician ever could. But it’s the album’s centerpiece “Not Dark Yet” that marks a highlight of Dylan’s entire body of work, not just his later years, as he sings: “Shadows are fallin’ and I’ve been here all day. It’s too hot to sleep and time is runnin’ away. Feel like my soul has turned into steel. I’ve still got the scars that the sun didn’t heal. There’s not even room enough to be anywhere. It’s not dark yet but it’s gettin’ there.”

It’s no stretch to suggest the song is 56-year old Dylan reflecting upon his own mortality. From the sounds of it, the man who once sang “He not busy being born is busy dyin’,” was still busy being born.

A Tribe Called Quest, “We The People” (2016)

This song was released one week after former President Donald Trump’s election in 2016. Though it sounds like a response to election results, the feelings were simmering long before The Donald took office. The song includes a pitch-perfect verse from the late Phife Dawg, who died months before the album’s release, but whose voice was stronger than ever.

Neil Young, “Hitchhiker” (2010)

Throughout his whole career, Neil Young has switched back and forth between two seemingly antithetical styles. There’s his signature spare, harmonica-kissed voice-and-acoustic guitar folk which gave him hero status and prompted his most successful material such as “Heart of Gold,” “Old Man” and “Harvest Moon.” He’s also an agent of sonic chaos, wrenching some of the most evocative electric guitar sounds in extended jams with “Cowgirl in the Sand,” “Like a Hurricane” and “Cortez the Killer.” The former role usually accentuates Young’s melancholic side while the latter is a vehicle for his undefinable anger, but in 2010, Young released Le Noise, a record that united the two sides of Young by framing him as solo but wielding an army’s worth of electric guitar feedback and gut-clenching rage.

“Hitchhiker” was a drug-hazed road chronicle originally written and recorded on Aug. 11, 1976, but never released. While the original solo acoustic recording feels like the tale of a steadfast troubadour living through life’s obstacles, the solo electric version obscures the song’s glorification of the past in a thunderstorm of electric guitar, like a distant memory from another life keeping you up at night that you just wish you could forget.

Iggy Pop, “Break Into Your Heart” (2016)

Iggy Pop is the godfather of punk for a reason – such as the stage diving, the chest cutting, the rabid ability to channel the most carnal of human urges in performance, the perpetual shirtlessness. In recent years he’s become known for his sporadic character acting in movies and TV shows such as Jim Jarmusch’s Coffee and Cigarettes, The Adventures of Pete & Pete (and possibly at his finest through a cameo as a disgruntled, Al Martino-loving Syracuse ice skating rink DJ in Snow Day), But the godfather of punk was waiting for the right moment to strike back.

While Pop’s 2016 comeback album Post Pop Depression was not exactly a return to form, it was undoubtedly a return of Pop’s unrestrained spirit. In the producer’s seat, Queens of the Stone Age’s Josh Homme wrangled a ragtag group of musicians including Arctic Monkeys’ Matt Helders on drums and QOTSA’s very own Dean Fertita on guitars and keyboards, and the band attempted to replicate the creative efficiency of Pop’s first two iconic solo albums produced by David Bowie: The Idiot and Lust For Life. As a result, Post Pop Depression is a burning hot desert rock masterpiece with Pop’s twisted charms front and center. The song’s opening track “Break Into Your Heart” sneers and growls like a coyote with the words “I’m gonna break into your heart, I’m gonna crawl under your skin.”

There’s nothing romantic about his intention. Pop’s repeated mission statement is one fueled by obsession and lust, not love. By the time the song reaches its own peak and descends, Pop’s voice is too close for comfort.

Tom Petty, “Saving Grace” (2006)

It’s amazing what one note can do. The muscular, John Lee Hooker-like riff to “Saving Grace,” the opening track on Tom Petty’s 2006 solo album Highway Companion, is just one note played with enough conviction that it holds up the entirety of the track. Undoubtedly one of Petty’s best rockers, the track features only three musicians: Petty, his right-hand man and lead guitarist Mike Campbell and producer/Electric Light Orchestra mastermind/fellow Traveling Wilbury Jeff Lynne. Campbell plays the song’s riff, Lynne plays bass and keyboards, and, surprisingly, Petty plays drums on the track, alongside doubling the riff with his own guitar.

In a stroke of genius, the song grows from its simple riff, with each instrument entering after each verse, revving and growing. By the time the drums enter after the third verse, the song is an all-out road-ready boogie monster – until the bottom drops out in the bridge and the song runs off the road. Much like the subject of the song – a girl whose restless drive to keep running through life in search of the next high keeps her from any kind of stability – the sole preoccupation of “Saving Grace” is to keep moving forward and avoid settling down at all costs.

U2, “Breathe” (2009)

It may not be their best album (that’s always going to be the eternal debate between The Joshua Tree and Achtung Baby) but 2009’s No Line on the Horizon might be the definitive U2 album.

Continuing their on/off collaboration with deity-like producer Brian Eno (who helmed the aforementioned pair of albums) No Line on the Horizon feels like the culmination of U2’s force in popular music, gathering elements from all of the band’s previous eras – from their post-punk roots, stadium-sized heyday, forays into electronic experimentation to their status as the definitive 21st century alternative rock band.

It all comes to a head in the explosive rumble of the album’s penultimate track, “Breathe.” Its bombastic three-note guitar-and-cello riff and piano twinkles allow Bono to gush one of his most free-associative lyrical performances, revolving loosely around June 16, a date known as “Bloomsday,” on which James Joyce’s novel Ulysses takes place. Several of Bono’s best-one liners emerge from the eruption, including a now-chilling premonition: “Sixteenth of June, Chinese stocks are going up and I’m coming down with some new Asian virus.”

Bono has never sounded so liberated and worry-free as he does on “Breathe,” and hasn’t sounded like that since. It’s almost as if despite the chaos of the world, for these five minutes, his lease on life is entirely self-determined.

The GZA feat. Tom Morello and K.I.D., “The Mexican” (2015)

A cover/interpolation of the influential 1972 art rock by the British rock band Babe Ruth, the Wu-Tang’s most linguistically lethal member takes the song’s foundational rhythm and hook and juices it up with the help of Rage Against the Machine guitarist Tom Morello into an essential part of the rap-rock vernacular. The 48-year old MC spins his sharpest rhymes in over two decades, so much so that the phrases “Socioeconomic circles,” and “Federal reserve notes and gold medallions” become razor-sharp hooks in themselves. Aside from his titanic influence on hip-hop as a part of the Wu, the case for The GZA’s goat status is all right here.

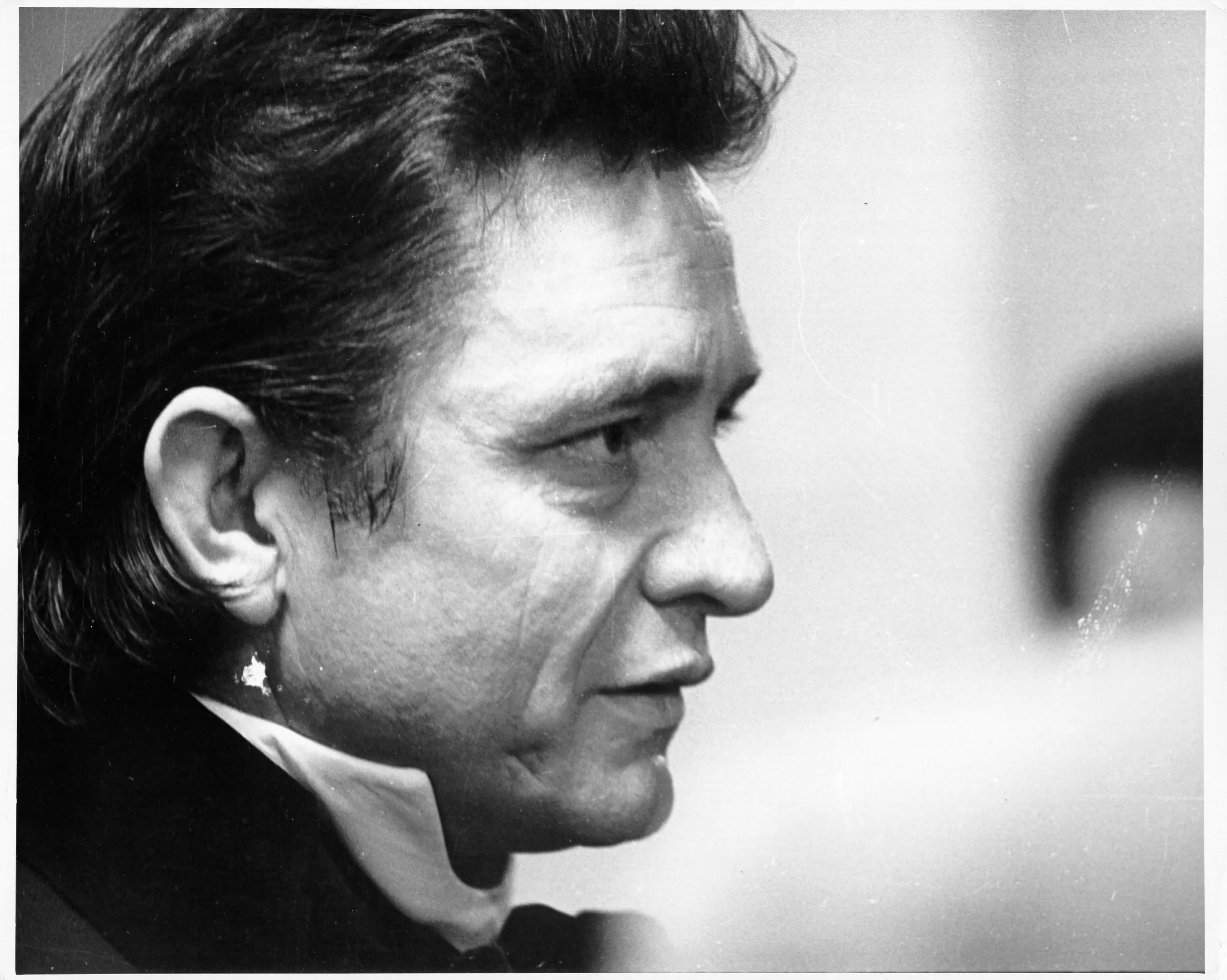

Johnny Cash, “When The Man Comes Around” (2002)

When country legend Johnny Cash re-entered the public eye in his final years, it was for his stripped-back Rick Rubin-produced covers of contemporary songs like Soundgarden’s “Rusty Cage,” Depeche Mode’s “Personal Jesus” and Nine Inch Nails’ “Hurt.” But in those last days, Cash’s pen moved one last time, resulting in one of his most chilling pieces of songwriting ever. “The Man Comes Around” is a Dylanesque retelling of the Book of Revelations, with Cash’s vulnerable yet steady voice sounding as intimidating as ever as he sang: “The hairs on your arm will stand up at the terror in each sip and in each sup. Will you partake of that last offered cup or disappear into the potter’s ground when the man comes around?” Even with the end drawing near, Johnny Cash was ready to put up a fight, as always, to the very end.

Joni Mitchell, “One Week Last Summer” (2007)

It’s all there. The regret. The heartbreak. The nostalgia. The memories fading like the setting sun, taking with them the bittersweet happiness from holding onto the pain from an old wound. “One Week Last Summer,” the opening track on Joni Mitchell’s final studio album Shine, has no words, but while Mitchell had long conquered the challenge of lyrical expression, her ability to convey these feeling through melody had reached its apex. With just a piano, saxophone, strings and choir, Mitchell evokes about as much in those five minutes as she ever had across a full LP. Whether it’s the can’t-live-with-you-can’t-live-without-you struggle of “Help Me” or the road-weary melancholy of “Hejira,” it all feels like a comedown from a happy memory.

Pink Floyd, “High Hopes” (1994)

How does one of the greatest musical groups of all time go out on a high note? In 1994, Pink Floyd had long survived original frontman Syd Barret’s succumbing to mental illness, and their longtime creative leader Roger Waters had been out of the band for nearly a decade. The band’s ability to move forward both musically and personally was proven, but their place in the swiftly changing musical landscape was not.

For the closing track of what was to be Pink Floyd’s final album, The Division Bell, singer/guitarist David Gilmour decided to take one last look back. For eight tear-jerking minutes, Gilmour and co. close the nearly 30-year career of Pink Floyd with “High Hopes,” a song that practically wraps up the band’s entire body of work into a single closing statement: “The grass was greener, the light was brighter, the taste was sweeter, the nights of wonder, with friends surrounded, the dawn mist glowing, the water flowing, the endless river, forever and ever.”

Queen, “Innuendo” (1991)

The public didn’t know it at the time, but Freddie Mercury was dying. He disclosed his HIV-positive status to his bandmates, and Queen decided that the only thing left to do was soldier forward until the inevitable. The band decided to go back to their roots for what was likely going to be Mercury’s final recorded statement with the album Innuendo. There are signs of Mercury’s state of mind across all of the record’s 50 minutes, but it’s the opening title track where the band captures everything they were ever good at in six-and-a-half glorious minutes: heavy metal stomp, operatic grandiosity, flamenco and Mercury’s stronger-than-ever voice. Nine months later, Freddy Mercury was dead, and “Innuendo” remains one of his definitive moments.

Yes, “Solitaire” (2011)

There have been so many versions of Yes in the last 50 years that it’s a minor miracle that this record even got made. Following the departure of founding lead singer Jon Anderson after health problems prevented his ability to tour, bassist Chris Squire, guitarist Steve Howe and drummer Alan White decided that it was best for Yes to simply move on with a new frontman. The trio recruited Canadian Benoit David, who had been part of a Yes tribute band. The resulting album, 2011’s Fly From Here, was Yes’ best work in over 25 years.

Produced by Trevor Horn (who was briefly Yes’ frontman on the underrated Drama), the album is a fresh start for a band that had been creatively struggling for the better part of three decades. Despite David’s much-needed presence, the album’s highlight is a piece of music solely composed and performed by Howe. “Solitaire” continues the tradition of his revered solo guitar pieces like “Mood for a Day” and “The Clap” and goes beyond that, featuring some of his most emotive and intricate fretwork ever – no shredding, no tricks.

Duke Ellington, “Money Jungle” (1962)

To say Duke Ellington was a titan in jazz is an understatement. In terms of jazz, Ellington, Miles Davis and John Coltrane are The Father, The Son and The Holy Spirit incarnated. Recordings of Ellington’s orchestras are still among the definitive jazz albums ever, and he remained a popular and beloved figure all the way up to his death in 1974.

But it’s one moment in 1962 that defined his open-mindedness. Ellington, 63 at the time, made a record with two of jazz’s foremost innovators: multifaceted drummer Max Roach, 38, and rambunctious bassist/composer Charles Mingus, 40. On the opening title track, one can immediately hear the vast discrepancy between Mingus’s thorny style of bass playing and Ellington’s classic jubilant swing, while Roach mediates the two rhythmically. Mingus sounds like he is attacking Ellington with his sharp jabs, and Ellington adapts to the best of his abilities. As a result, Ellington’s playing is rougher and more aggressive than on nearly any other recording. Subsequently, Roach’s drumming is some of his most exciting. ‘Tis the beauty of jazz.

David Bowie, “Blackstar”

There’s not a word to be said about Blackstar that hasn’t already been said, given its release was only five years ago, most discussions revolved around the timely release of David Bowie’s final album three days before his death. But the titular song on the album may be the single greatest late-career masterpiece ever created. Enough said.