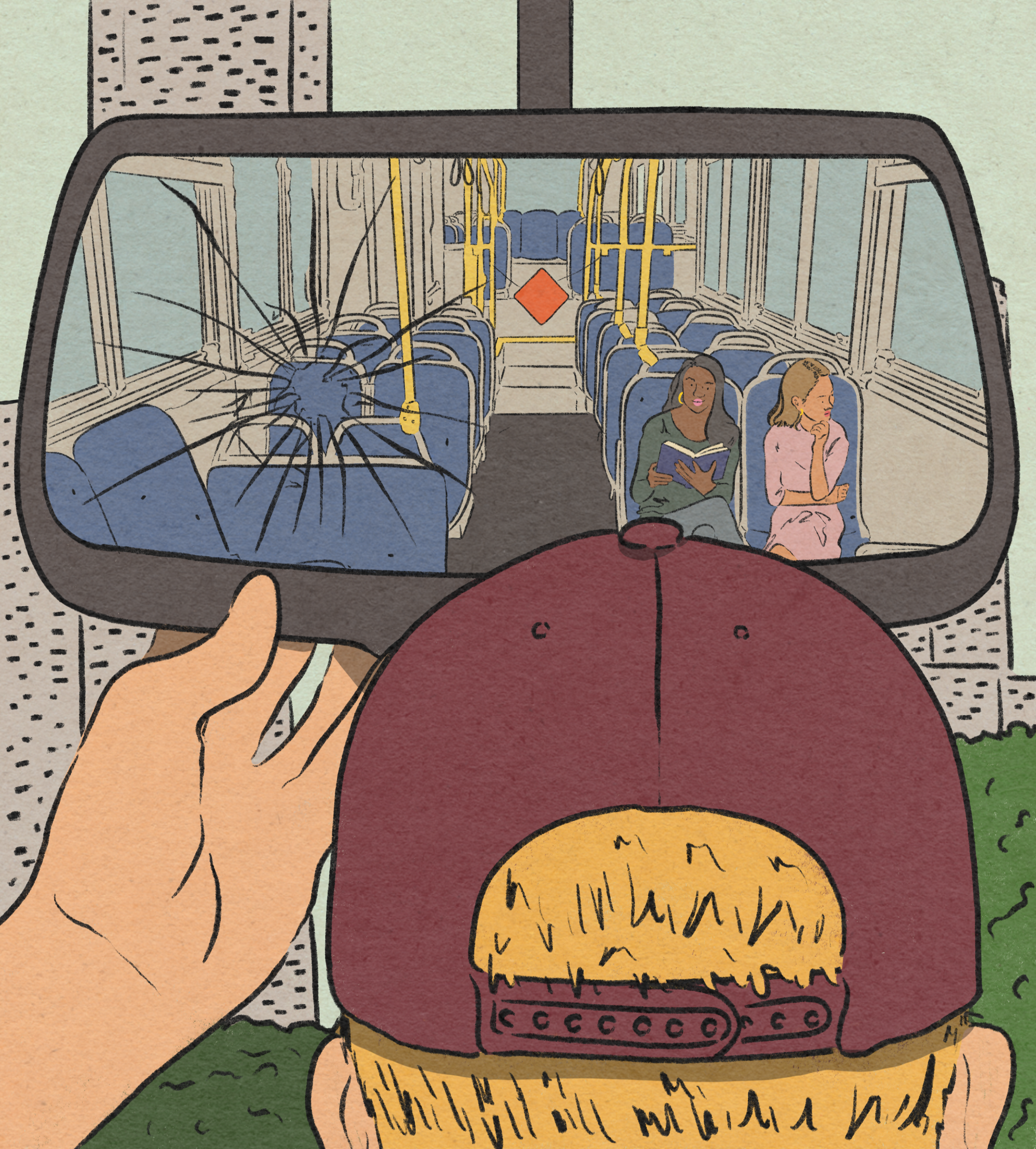

Illustration by Tatyana Alanis

Audio By Carbonatix

After six years behind the wheel of a Dallas Area Rapid Transit (DART) bus, Sandra Cooper is embarrassed to say she still doesn’t know the streets of Dallas well. She knows major landmarks, like the NorthPark Mall, but street names are tricky for her to recall.

For instance, she remembers being near the shopping center the second time she experienced a DART bus powering off mid-ride last year. She remembers the road being busy, but as for which road the incident happened on exactly, that’s where things start to get a little bit fuzzy.

What she does remember is the feeling of clenching her hands around the steering wheel, which, without power steering, seemed impossible to move. The fate of herself and of her riders suddenly felt fragile as every worst-case scenario played out in her mind.

“You can’t turn [the steering wheel], so I had to hold it to try to make [the bus] go straight, and then ease down my brake and try to move out of the way so nobody ran into me. I don’t want to slam on the brakes because I’m worried about who might smash into me,” Cooper told the Observer. “But really, when it shuts off, I’m not even thinking about the back. I’m looking to the front, trying to make sure I don’t run into a wall or something.”

That sort of thing didn’t happen when Cooper started her job, but these days, she’s surprised it doesn’t occur more often and with a worse outcome.

Cooper is one of five current or former DART bus drivers who spoke to the Observer about a culture of neglect pervading the transit agency. Drivers described a fleet of broken buses moving across the city, and a system that has failed to protect the people charged with getting Dallasites to where they need to go. Injuries to hands, shoulders, backs and necks are commonplace, the Observer was told, and medical care for those injuries is kept behind lock and key.

“They already know these vehicles are damaged and falling apart, because all of them fell apart in that heat last summer. They’re endangering the public’s lives,” Cooper said. “It’s our lives, and the public’s lives, and they’re sending us out there.”

Responding to the claims in this article, Jasmyn Carter, director of public relations for DART, emphasized the organization’s commitment to its employees. Carter added that many of the concerns voiced in this article are issues that are covered during the multi-week training divers undergo before hitting the road.

“Our leadership roundtable is very aware of the things that our people are doing to keep DART moving,” Carter said. “We know that rail and bus [driving] is not easy every day, but we try to make sure that we give them the best quality response times and services and leadership. When these [employees] call, it’s not lost upon us the hard work that they do.”

Get Off the Road

Nearly 700 buses make up the DART fleet, with 522 of those being used daily. While Cooper said she has encountered more mechanical problems the longer she’s driven the buses, most issues aren’t as dramatic as a full power shutdown in the middle of a busy thoroughfare. Oftentimes, she’s dealing with mundanities like a finicky seatbelt that has to be tied to the seat because it won’t click into place.

“All the buses are broken,” Cooper said. “There’s smashed in headlights that, instead of pointing to the ground, they point up at the trees so we can’t even see what’s in front of us.”

In many cases, the state of the vehicles is more frustrating than dangerous, said Ryan Morris, a driver who recently left DART. Morris and Cooper, along with each of the other drivers interviewed for this article, have been given pseudonyms to preserve their anonymity. In some cases, the drivers who spoke to the Observer are still employed by DART, and others are now employed by other municipalities or transit agencies.

Sometimes the problems with the buses are purely mechanical. Whether or not a bus window can open is a 50/50 bet, Morris said. He’s made do with everything from a bent-out-of-shape steering wheel to dashboards held together by duct tape. When the COVID-19 pandemic started, the agency built clear security shields around the bus operators. Morris estimates 70% were rolled out without latches. Eventually, drivers found ways to use a transfer card and a plastic garbage bag to MacGyver the shields closed, he said.

More than a dozen images and videos of equipment provided show ripped seats, chipped plastic dashboards, unanchored fare machines, loose side mirrors, wobbly driver’s seats and bus kneels – the feature that allows the loading side of a bus to lower itself to the curb – that are too high.

In other cases, the grime is manmade. He once ended a long day by finding feces dropped discreetly in the back corner of his bus. He is visibly skeeved out, recalling the “very disgusting” conditions he occasionally encountered while a driver.

“The [leather seats] have rips and tears in them, and some people get bit,” Morris said. “It sounds crazy, man – the cushion is actually showing, like the little yellow part, and some people actually got bed bugs from the DART bus.”

According to Carter, the seats in all of DART’s buses were switched to a vinyl material in 2024 “to ensure cleanliness and minimize the risk of pest exposure.” The buses also undergo daily cleaning and disinfection and routine pest control, she said.

Candace Martin, a driver who says she lost her job after suffering an injury that left her unable to work, said that the lifts meant to accommodate wheelchair users often broke down and had to be manually operated. The lifts are required for compliance with the Americans with Disabilities Act, and Martin said when she’d occasionally call a dispatcher to report faulty wheelchair lifts, she’d be given instructions on how to work the machinery herself.

Many of the mechanical issues that drivers noted have simple fixes that are taught in driver’s training, Carter said. For instance, drivers are taught how to operate wheelchair lifts electronically and manually, and a lift is not considered truly faulty if one of those two options is still functioning. For more serious malfunctions, drivers are able to report vehicles to a mechanic shop using a defect card system, Carter said.

But drivers said reporting an issue often does little good.

Irene Garcia, a driver for nearly a decade, said that when a bus is damaged, drivers drop it off at a mechanic shop, where they fill out a defect card detailing the issue that needs to be repaired. For years, Garcia said she believed that the process was truly solving the problems she was reporting. Then she “started paying more attention” and began to believe the defect cards were often little more than a symbolic formality.

“They’d just give me right back the same bus,” Garcia said. “I just told them that that bus just hurt me, and they still give me back the same one.”

Cooper has witnessed the same system of buses being taken in for repair, only to be handed back in what she believes to be a similar condition. She once had a bus blow an air bellows – a tire-like device that acts as a spring to soften the jerkiness of a bus – and was shocked to see the vehicle returned to the fleet less than 24 hours after turning it in because she suspected that not enough time had passed for the problem to be adequately addressed.

“There’s often been times I come back and that same bus is back out there,” Cooper said. “And I’m like, I know they couldn’t have fixed that bus that fast. … That’s how people’s buses shut off on the freeway. I had told them there’s something wrong with that bus.”

According to Carter, buses undergo a thorough inspection every three to four weeks or every 6,000 miles driven. The average lifespan of a bus is 12 years, and though the organization has approved the purchase of 400 brand-new vehicles, it’s unclear when those will be rolled out.

Dealing with any vehicle requires maintenance, Carter said, and it’s true that some things “are always going to have to be fixed over and over again.” But she feels confident in the ability of the DART mechanics to ensure that no drivers or passengers are being put onto dangerous vehicles.

“We know how many miles we have to drive and we know how many stops we have to make. And so sometimes, if there is something as simple as putting power steering fluid in a bus, that does not take all day. That may not take long at all,” Carter said. “But the other part is, we are very well aware that our system is old.”

DART bus drivers switch shifts.

Jacob Vaughn

Major Pains

Martin was four months into her job as a bus driver in 2023 when she suffered a hand injury that made driving nearly impossible.

It was the dog days of summer, and she was driving down Westmoreland Road when it came to an especially tricky point in her route. She needed to make a right turn onto a “small, narrow street” that was lined with cars on the right side, and had a fire hydrant located precariously close to the curb on the left side. The speeding traffic surrounding the bus added to the list of obstacles.

She’d need to make a wide approach before turning tightly into the street, she thought to herself as she prepared to “execute.” Martin exerted herself against the bus’s steering wheel as she began the turn, and felt a throbbing pain “shoot up her arm.”

“I feel this stinging and I’m like, ‘Oh!’ So I stopped [the bus] and I was like, ‘Oh my God, my hand.’ There was a passenger on the bus and they said, ‘You need to pull over,'” Martin said. “I was holding my hand and I just said, ‘Give me a minute. Give me a minute, guys. Something’s going on with my hand.'”

Martin was able to pull over for a few minutes to manage her pain, but in the back of her mind, a clock was ticking as she thought about the time frame she was expected to make her stops within. She “got herself together” and managed to drop off her riders before heading back to the driver’s home base. By the time she located a supervisor to report the injury, her hand was hurting “severely.”

According to Martin, she attempted to report her injury the day it was sustained, but was told by the supervisor that she had not been employed long enough with DART to make a report.

“She showed no compassion,” Martin said. “She said, ‘I could give you a couple of days off,’ and she did. I came back and I went and got a brace for my hand, and then she told me, ‘You can’t drive with that brace on.’ … My hand was still hurting, but I went back to work because I had to feed my family.”

Martin reached out to a DART driver union representative about the situation, but was offered little more than driving tips.

A week later, Martin was able to file an injury report with a different supervisor. By that point, her hand and fingers were swollen and in “excruciating pain.” A doctor within the DART workers’ compensation network told her she likely had carpal tunnel syndrome. She was given oral medication, but it didn’t work. A few weeks later, a doctor prescribed steroid shots for Miller’s hand, which she describes as “the worst pain ever.”

Martin said the several months she was out of work to take care of her hand were an “awful time” for herself and her family. She was in pain and out of money. Martin said DART declined to grant her short-term disability pay during the time she was out of work and receiving medical care.

“We didn’t have a Thanksgiving, we didn’t have a Christmas,” she said. “It was just the most horrible thing I ever went through.”

Martin was still receiving care from a DART doctor for her hand when she was notified by her supervisor – the one who she says initially declined to take a report on the injury – that she could either return to work or lose her job. She tried to fight that decision, which she believes is unethical and potentially illegal, but eventually had to “cut her losses.” The pain in her hand was too severe to return to work, and she was terminated.

After that experience, Martin attempted to get a job with the Lancaster school district as a bus driver, but she failed the physical exam for the job. After going through an evaluation, she was told her right hand lacked the strength needed to operate a major vehicle.

While the Observer was not able to share further specifics of Martin’s case with DART to protect Martin’s anonymity, Carter confirmed that Martin’s supervisor should not have used Martin’s short time working with the agency as an excuse not to take an injury report.

Other drivers mentioned similar stories about suffering injuries on the job and being required to jump through hoops to be seen by a doctor. Several drivers suggested shoulder injuries are the most common among drivers because of the strain of navigating the hefty steering wheels.

Garcia has had multiple surgeries on her shoulders, but getting DART to take accountability for those injuries has been a years-long process. The most recent ruling Garcia received from a DART-network doctor is that her injuries are not related to her profession. A doctor’s report describes “high-grade” tearing throughout her rotator cuff and biceps tendon and mild muscle atrophy that has occurred since her last surgery.

“They’re causing injuries, repeat injuries to different people,” Garcia said. “And this is negligence. We shouldn’t have to be hurt.”

Over the years, Garcia has lamented to friends and family about her “torn up” shoulders. Eventually, a mutual friend directed her to Regina Stevens. Stevens is a senior workers’ compensation adjuster for a company that handles claims for municipal agencies. While the company does not work with DART directly, her name has been changed in this article because her work overlaps with adjacent agencies.

Stevens told Garcia she’d take a look at her injury history and communications with DART’s workers’ compensation adjusters as a favor – there likely wasn’t much Stevens could do, she warned, other than offer some advice. What she saw was startling.

Based on Garcia’s injury history and documentation, Stevens does believe DART is responsible for the shoulder injuries and should be paying for Garcia’s treatment.

“The red flag is the fact that they keep putting their bus drivers in these broken buses. If you know that your buses or equipment need repair, it’s completely unethical to continue to put the drivers behind the wheel,” Stevens said. “It’s an interruption in life for these bus drivers. They’re getting injured, they need surgeries, and from my understanding, a lot of the drivers are having similar injuries to the shoulders. The shoulder is a very, very difficult surgery to recover from.”

Equipment isn’t always to blame for the injuries bus drivers sustain. Quintin Baker, a driver for over a decade, was left unable to drive after his bus was rear-ended while parked. Baker was standing in the bus at the time of the accident and suffered a strain to his neck and back. DART approved him for a handful of visits to the physical therapist, and in the meantime, he was off work and being paid a portion of his salary. In the weeks that he waited for his first appointment, the pain intensified.

“My muscles had gotten worse and my injury was a little worse, and I was barely walking by [the time physical therapy started] because so much stuff had gotten stiff and out of place,” Baker said. “[After the visits] I was like, ‘Man, I think I need some more therapy.’ Because I was still having trouble turning my torso. When you drive, you need to be able to turn to look back over your shoulder. With the length of the bus, you have to be able to see a good distance on each side of you.”

Baker was eventually moved into a DART department that does not require him to operate a vehicle because of his injury. Months after he’d been hurt, Baker said he was instructed to see a new doctor within the DART network for an evaluation. That doctor disagreed with his prior diagnosis, and Baker was told he’d have to begin paying DART back for the treatments he’d received. It will take him two years to pay off the balance.

“The hardship it puts me through, man,” Baker said. “It was a nightmare.”

Riders board a DART bus. Ridership has never bounced back to pre-COVID numbers.

Jacob Vaughn

A System Under Pressure

While DART has made strides to improve ridership in recent years, the number has never really bounced back to pre-COVID highs. Nearly 20% fewer riders took the DART last year than in 2019. While customer satisfaction in the transit agency topped 70% last year, some Dallasites still have to hold their nose to even consider utilizing the system.

Nationally, transit agencies have seen a spike in onboard crime since COVID-19, and in 2022, the organization reallocated $110 million to advanced security measures to help restore community trust in the transit system.

Nonetheless, the drivers themselves often don’t feel safe while carrying out their jobs, the Observer was told. In 2023, a study by Urban.org found that “major assaults” on transit employees, defined as assaults resulting in a fatality or injury that requires medical transport, had tripled across the United States over the prior 15 years. Bus drivers are almost twice as likely to be involved in a major assault as a rail worker, the study found.

“A lot of operators have been assaulted very badly, but when that stuff happen, that’s when [DART] really wants to start being your friend,” Morris said. “Like that’s when you can probably get your vacation day that you put in a request for two months ago.”

Cooper and Martin both said they have witnessed shootings that left them emotionally distraught. In Martin’s case, a shooting near her bus resulted in bullets “flying by the driver’s window,” and she pressed a panic button that is located near the driver’s seat and alerts the agency to an emergency. DART police officers, though, never showed up, she said.

Carter said the average wait time for DART police is between six and 12 minutes, but that the specific location of the shooting Martin witnessed could have meant the case was transferred over to the Dallas Police Department. Even if the case wasn’t within DPD’s jurisdiction, Carter added, DART police operate on a priority basis where calls with a victim are prioritized. Because there was no victim in Martin’s case, police could have been prioritizing more severe calls elsewhere.

Cooper said she has experienced riders brandishing knives and guns while on her bus. On one occasion, she said she overheard two riders get into an altercation that escalated into threats to shoot a weapon. She pressed her panic button discreetly, and said the phone in her bus began ringing soon after. Cooper believes that the call violates DART’s policies and that monitors should have been able to tune into the bus’s cameras to see the situation for themselves.

“I didn’t want to dare pick the phone up and get shot, because [the riders’] would know that I pushed the button,” Cooper said. “[The cameras] work when DART wants them to work. For example, if you have an earbud in, oh, they saw you with the earbud in. But they don’t see you when a gun is out or when a knife is out.”

In Cooper’s experience, DART police officers have been slow to respond in incidents like the threat she overheard, a problem that could be further exacerbated if a bill labeled the “DART killer” is passed by the state legislature.

House Bill 3187, filed by Matt Shaheen of Plano, advanced out of committee earlier this month. The bill calls for a 25% reduction of the one-cent sales tax that is paid to DART by member cities, a funding cut that DART officials say would result in “a full-on dismantling” of the system.

In a preliminary forecast shared with the DART board of directors earlier this year, DART Chief Financial Officer Jamie Adelman warned of a workforce reduction of nearly 1,000 people if the bill passes into law. Adelman said nearly half of those layoffs would be bus and rail operators, with fare enforcement and transit security positions likely also being cut.

A more recent estimate puts that workforce impact at 5,800 jobs, according to a May news release from DART. While that release does not clarify what roles would be slashed, it does claim services would need to be reduced by 30%, “undermining DART’s ability to prepare for major international events like the 2026 FIFA World Cup.”

Legislation like the “DART killer” bill would threaten the jobs of the individuals who are still driving for the agency. It could also make the issues currently facing bus drivers even worse, Jeamy Molina, an executive vice president and chief communications officer for DART, said.

“If HB 3187 comes to pass, all of these issues that [the Observer] is talking about not only get exacerbated, but it will stop service to 30% of the area here in North Texas. We won’t be able to get new buses,” Molina said. “Like [the Observer] heard from drivers, we know [the buses are] old and we know that it takes time to work on them. Our mechanics are having to do a lot of work, and that’s only going to get exponentially worse year after year.”

HB 3187 failed to get a second reading before the May 15 deadline, likely killing its chances, however, an identical Senate bill, SB 1557, remains alive.

Garcia, the driver whose shoulders are “all torn up,” can’t find it in herself to care about Molina’s dire warning.

“They’re reaping what they’ve been sowing,” she said. “[DART’s] not transparent, so you reap what you sow. You’ve been doing it quietly and silencing us [drivers], and doing this evil to us, so I believe it just comes back on you.”

Cooper shared that lack of sympathy. She’s in the process of trying to get seen by a doctor for a new injury, which was caused when her 30-foot bus hit a seemingly innocuous pothole and lurched forward, throwing her against the steering wheel and her seatbelt.

“It makes you upset, it makes you uneasy, it makes you not even want to go to work,” Cooper said. “But you go, because, I mean, you need the money to live. I’m not trying to be homeless.”