Brian Maschino

Audio By Carbonatix

A single porch light shined on a white mobile home one mid-July night in a rural neighborhood north of Dallas, illuminating drops of blood that trailed down the porch’s faded blue wooden steps. More blood pooled at the bottom of the steps and stained the porch’s handrail and floor.

Along this bloody trail lay the Taurus .45 semiautomatic handgun and empty Coors Light beer can Joshua Davies dropped when he pulled the trigger. A crime-scene investigator collected a single spent shell casing from underneath a plant. Davies’ blood and flesh flecked the gun’s barrel, inside and out.

There was no mystery here. Davies shot himself in the head in front of his little sister as she spoke to a 911 operator. She stopped mid-sentence when the gunshot erupted but ended the call screaming.

This wasn’t the first time Davies’ family had called 911. They tried several times this summer to get Denton County sheriff’s deputies to take him for a 72-hour evaluation at a mental health clinic. His mother, Leigh Allison, says that was their only option because Davies wouldn’t seek treatment on his own.

An intake counselor at Santé Center for Healing, an addiction treatment center in Argyle, told Allison she could have police escort her son there if he were a threat to himself or others. Instead, she says, sheriff’s deputies offered to take him to jail for damaging property but refused to take him to a behavioral health facility because he hadn’t harmed himself or anyone else.

“All I had to do was tell the police that is what I wanted them to do [the next time he had an episode],” she says. “I did not want to press any sort of criminal charges against him. I just wanted him to be compelled to go through this assessment. Santé assured me repeatedly that the police would accommodate this request with adequate compulsion.”

Instead, case files show that Davies told officers he was only acting distraught and destroying property because his girlfriend wasn’t interested in their sex life.

“[He] stated that it was against his religious beliefs to harm himself or any other persons,” a June 16 incident report reads. “Based on the above information, the investigator did not determine that [Davies] was suicidal, homicidal or in a deteriorating state of mind presenting a danger to himself or any other persons.”

The Denton County Sheriff’s Office didn’t respond to requests for an interview.

A month later, Allison’s 37-year-old son was loaded into an ambulance and taken to a hospital emergency room, where he died from a self-inflicted gunshot wound to the head.

“I don’t know what the deal is, but I followed the rules,” Allison says. “That is what I did with Joshua. I needed help for my son. What do we need to do? I’m telling you that he’s suicidal, his friends are telling you that, his girlfriend is telling you that, but all [the sheriff’s office] wants to do is arrest him and give him a criminal record?”

Before Davies killed himself in front of his, sister Ashleigh Allison, he smashed out windows on his and his family’s vehicles. Denton deputies offered to take him to jail for property damage but wouldn’t take him to a mental health facility despite his mother’s pleas.

Brian Maschino

Same Old Story

Davies’ case is a familiar story for law enforcement, one that’s been unfolding since the deinstitutionalization of state mental patients beginning in the 1960s and the failure of community mental health centers in the 1970s.

“The records show that the politicians were dogged by the image and financial problems posed by the state hospitals and that the scientific and medical establishment sold Congress and the state legislatures a quick fix (over reliance on drugs) for a complicated problem that was bought sight unseen,” The New York Times reported in 1984.

Decades later, conditions are not much better. More often than not, people with untreated severe mental illness end up in court, in jail or dead. In January 2016, the University of Texas published an op-ed by Dr. Octavio Martinez Jr., executive director of the Hogg Foundation for Mental Health in Austin, headlined “Let’s Stop Treating Mental Illness Like It’s a Crime in Texas.” Martinez argued that the number of people with mental illness filling county jails in Austin, Dallas and Houston is a clear indication that “our communities don’t have the capacity to meet the demand for mental health services for all those in need, leaving jails and prisons to serve as de facto asylums.

“Our communities don’t have the capacity to meet the demand for mental health services for all those in need, leaving jails and prisons to serve as de facto asylums.” – Dr. Octavio Martinez Jr.

“This leads to a vicious cycle in which people with mental illness are retraumatized, released and then reincarcerated,” he told the Observer by phone.

Martinez says that among a list of 900 people who had been in and out of the Harris County Jail in Houston at least five times – some of them more than 30 times – 538 were diagnosed with untreated mental health issues. The Lew Sterrett Justice Center in Dallas, he says, is the second-largest mental health facility in Texas, and 25 percent of its inmates participated in NorthStar, once the county’s main mental health provider. The program was phased out at the end of 2016.

The North Texas Behavioral Health Authority now manages the mental health services for the county, and it has shown some improvement, says Charlene Randolph, director of the Dallas County Criminal Justice Department. The county has initiated several programs to combat jail recidivism among people with mental illness, including mental health personal recognizance bonds for low-level crimes and the Crisis Services Project, a program that helps identify inmates with mental illness and coordinate care with community-based services upon their release. From September 2016 to September 2017, Randolph says, out of 7,549 inmates participating in the program, 1,997 returned to jail.

“We have a wrap-around team and a discharge team because they may need some extra hand-holding as they move through community services,” she says. “Some may need housing, and so there is a team that wraps around them and tries to get them a place to stay.”

Beyond Dallas, county jails nationwide are dealing with 10 times as many people with serious mental illness as state psychiatric hospitals, according to a July 14, 2016, report by the Treatment Advocacy Center, a nationwide nonprofit organization seeking to improve mental health treatment laws. State psychiatric hospitals have seen a 17 percent reduction in beds since 2010, and most states maintain waiting lists for beds that can take months to obtain, says John Snook, the center’s executive director.

That leaves law enforcement officers on the front lines to deal with mental health crises, a task few are well-equipped to do. Of 77,000 licensed peace officers in Texas, only 7 percent have received the additional 40 hours of training to become certified mental health officers, the Texas Tribune reported in May. With 10 percent of service calls to police involving someone with a mental illness, it’s not surprising that at least half the people killed by police each year have mental illnesses, according to a 2013 report by the National Sheriff’s Association and the Treatment Advocacy Center.

“Law enforcement get involved when someone with mental illness is acting out violently, but the reality is the person is in crisis,” Snook says. “The first call shouldn’t be to the police. The first call should be to provide treatment.”

But there’s no 911 system for psychiatrists, and law enforcement officers are trained to do just that – enforce the law by catching criminals. In Davies’ case, officers decided that without reason to arrest him and take him to jail, they would leave him be. They had another choice. It might have saved a sick man’s life.

Ashleigh Allison at the trailer where her brother killed himself.

Brian Maschino

Teaming Up

Someone had called 911 in Harris County to report that a man planned to run onto Interstate 10 to kill himself, Harris County Assistant District Attorney Bradford Crockard wrote in his article “Beginner’s Guide to Involuntary Commitment.” Houston police officers arrived at a dilapidated residence outside downtown Houston, where they encountered a man Crockard called “John.” He was lying on a mattress surrounded by food wrappers, trash and a bottle of King Cobra malt liquor. Officers asked John if he told someone he planned to kill himself, and he said yes. Then he became irate and accused officers of trying to arrest him when all he wanted was help.

Instead, the officers contacted Houston police’s Crisis Intervention Response Team, a group of specially trained officers who ride with clinicians from the local mental health authority. They calmed John down and persuaded him to open up about his mental health issues and drinking problem. He agreed to be taken to the Neuro-Psychiatric Center of Harris County.

“Upon arrival, the officer prepared a peace officer’s application for detention,” Crockard wrote. “Under oath, she stated that she had reason to believe that John was mentally ill and posed a substantial risk of harm to himself and others. The officer affirmed that immediate restraint was necessary to prevent an imminent risk.”

The Crisis Intervention Response Team is a model used by more than 2,600 communities around the country, including Dallas, Denton and Tarrant counties. It brings together law enforcement, mental health providers, hospital emergency departments, and individuals with mental illness and their families. By providing officers 40 hours of intensive training, it aims to improve responses to people in crisis and focus on diverting people with mental illnesses from jail to treatment.

San Antonio and Bexar County’s behavioral care system is widely accepted as a national model. For more than a decade, the city and the county have been working together to improve coordination among institutions and boost mental health crisis training for emergency responders. They’ve built a crisis center for psychiatric and substance abuse emergencies and a 22-acre campus for the homeless. They say the system has diverted more than 100,000 people from jail and emergency rooms to treatment and saved nearly $100 million in an eight-year period by “taking decisions on treatment and medication out of the hands of the most severely ill,” according to a Dec. 10, 2016, Boston Globe report.

In November, the San Antonio Police Department’s mental health unit hosted a weeklong training course in crisis intervention at the First Church of Nazarene in San Antonio for law enforcement officers from across Texas.

Since her brother’s death, Ashleigh Allison works for a crisis text line to connect others who are experiencing emotional distress to resources.

Brian Maschino

“The biggest thing we want you guys to do is to really focus on reassurance of safety,” Officer William Kasberg from SAPD’s Integrated Mobil Partners Action Team told the officers, according to Texas Public Radio. “Paranoia, if they demonstrate any signs of paranoia, reassure them that they are not in trouble. Nobody is going to hurt you.”

Although the state requires police officers to have 16 hours of crisis intervention and mental health code training before they start patrolling, some police departments demand more. Dallas police collaborated with Mental Health America of Greater Dallas to provide a 40-hour mental health crisis intervention training course for all patrol officers in 2006. It also has a crisis intervention unit that includes licensed social workers and counselors. The unit doesn’t respond to calls from the public but receives cases from police superiors and Dallas Fire-Rescue officials.

Dallas Fire-Rescue also launched Rapid Integrated Group Healthcare Teams to divert people with mental illness to treatment instead of jail. The Meadows Mental Health Policy Institute oversees the program, and the teams include paramedics, specially trained police officers and mental health clinicians. It’s designed to help respond to the more than 15,000 behavioral health calls 911 receives each year in Dallas.

The beta launch of the program occurred in late November and early December, and the full launch will take place in January. The hope is to free police officers to focus on public safety, to reduce Dallas County’s high recidivism rates and to lower costs associated with the improper care people with mental illness often receive in jail.

“Answer for mentally ill is not more arrests,” Dallas police Maj. Max Geron wrote on Twitter after the program was announced. “New approach will help alleviate problems and get help to more people.”

For two years, Denton police officers have gone through crisis intervention training updates that covered health and safety codes; conditions such as depression, bipolar disorder, schizophrenia and post-traumatic stress disorder; and how to identify people in crisis.

“Our officers are not clinicians, so we don’t attempt an exact diagnosis,” Denton police Chief Lee Howell says. “These courses are more about being aware, knowing how to approach people, teaching people to listen and observe, ask the right question and gauge the need for professional assistance, then refer or summon the right persons to help.”

Like San Antonio and Bexar County, Denton County has also taken strides to divert people with untreated mental illness from jail to treatment. Howell points out that along with the sheriff’s dedicated Mental Health Unit, the Denton County Mental Health and Mental Retardation Center operates a 24-hour triage facility. The latter has diverted 250 people from arrest, he says. Also, Denton County’s Mental Health Treatment Court allows qualified offenders with mental illness to have their criminal records wiped clean if they complete the requirements set forth by the court.

But for a diversion to work, a crisis intervention investigator has to recognize the signs of untreated mental illness.

Allison’s son wasn’t given the option to go to MHMR’s 24-hour triage, which his family wanted, or the county’s treatment court, where he may have appeared if he’d been arrested. The crisis intervention investigator didn’t recognize the signs of untreated mental illness but instead reported the signs as emotional distress from an unhealthy relationship. Davies’ ex-girlfriend recalls his words the day after the sheriff’s deputies left:

“Thanks a lot for embarrassing me,” he said. “I had to put on a good show and pour my heart out and cry.”

“You need help,” she replied.

“When you’re mentally ill, you don’t see you’re the problem. You see the situation is the problem. People are the problem, but you’re not the problem. So why do you need help?” – Leigh Allison

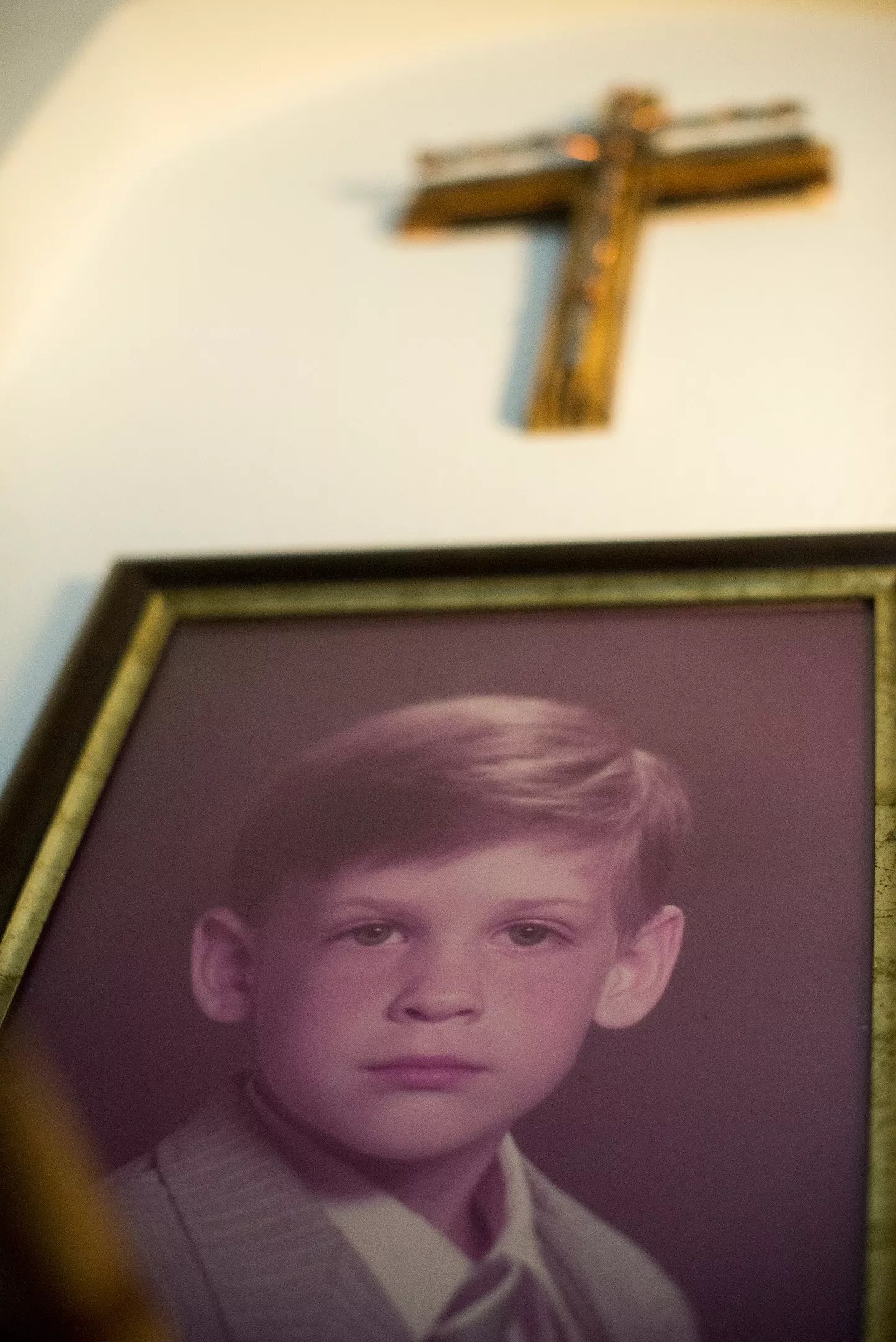

Allison tried to get her son help. Surrounded by photographs of him framed on the walls of her home near Texas Motor Speedway, she recalled calling her insurance company and contacting her son’s workplace to find out if any mental health services were available. But none of that mattered because he wasn’t willing to seek help.

“When you’re mentally ill, you don’t see you’re the problem,” she says. “You see the situation is the problem. People are the problem, but you’re not the problem. So why do you need help?”

At 6-foot-7, Davies towered over his mother and siblings. Allison met his father while they were serving together in the Marines. They separated when Davies was 2 and divorced when he was 5, and his father wasn’t involved in his life.

He never played basketball or joined the military like his parents. Allison says a childhood eye injury prevented him from doing so. He was carving bark from an old tree at his grandmother’s house when he slipped and stabbed himself in the left eye with a chisel. It caused his pupil to split open. He called it his evil eye.

Davies was the kind of child who struggled to sit still and eventually received a diagnosis of attention deficit hyperactivity disorder. Diagnoses of anxiety and bipolar disorder were later added, Allison says, but since he was an adult, it was much harder for her to make sure he was getting the help he needed.

Allison says the first signs of her son’s anger appeared when he began having issues at work about four years ago. He was in his 30s, employed at a warehouse in Grapevine and living with his girlfriend, whom he’d met on a dating app. They had a child together, but they weren’t a happy family. Davies had problems with alcohol and refused to be a family man, says Theresa Winkleman, his former girlfriend. He raged over small things and took antidepressants that he later told his sister weren’t working.

A violent outburst led to the first of four 911 calls throughout June. Davies broke out car windshields, smashed the driver’s side door of his pickup and threatened to harm Winkleman if she didn’t shoot and kill him.

“You can make it look like a suicide,” she recalls him telling her.

Denton County sheriff’s officers showed up wearing tactical gear after the first 911 call to Davies’ house, Allison says, and spent the next hour talking with him as his neighbors in the mobile home park watched. Deputies called it a mental health evaluation in their report, and Allison hoped the crisis intervention team’s observations and witness statements about his suicide threat would compel the team to take him for a 72-hour evaluation.

As the deputies began packing up, the crisis intervention investigator walked over to Allison, who recalls him saying, “Your son is better now that I have talked with him. Your son is in a bad marriage. He just needed someone to talk to. He promised to go to counseling.”

“What about the threats?” she asked. “What about him talking suicide? What about the guns? He is not married. She is just a girlfriend, and he is playing you if you think he is going to get counseling. I have tried to get him into counseling for years. He has lied to placate me and never gone. You do realize he has mental health issues, and he will say whatever he needs to in order to get away from being threatened by the cops?”

Winkleman says the investigator told her she and Davies should seek counseling at an area church and wrote down a suicide hotline number for Davies.

“I begged the cop to take him to get help,” she says, “but the cop just cut me off, saying the best thing for us would be to just try the couple’s counseling. … They just told me that he wasn’t suicidal. No physical signs that he hurt himself. It was his word over mine.”

Allison remembers looking at the investigator with tears in her eyes and telling him, “You are killing my son if you leave.”

Leigh Allison blames Denton County deputies for failing to help get her son mental health care.

Brian Maschino

From Sister to Activist

Ashleigh Allison still lives in the mobile home where Davies ended his life. Since completing her fall semester at the University of North Texas, she’s been spending all night in front of her computer working for a crisis text line to connect others who are experiencing emotional distress to resources. At 21, she also volunteers for Active Minds and To Write Love On Her Arms, both national organizations dedicated to raising awareness of mental illness and ending its stigma.

She didn’t know her older brother very well growing up because of their 16-year age difference, but the siblings grew closer in the last two months of his life. Ashleigh Allison moved into a home in the same neighborhood on the outskirts of Ponder, and Davies visited frequently after Winkleman left him and moved into a house across the street from their old home.

Like her mother, she tried to get her brother help. She even persuaded him to go to one of the counselors mentioned in a pamphlet the sheriff’s deputy had given him, but he changed his mind at the last minute.

“In his mind, he didn’t see anything wrong,” Ashleigh Allison says. “In his mind, it all made sense.”

The day she called 911 in mid-July, her brother was drunk and upset that Winkleman didn’t respond to his texts about giving him a ride home from work. He planned to work overtime to pay child support but was having car problems. Winkleman didn’t respond to his text messages because he’d been verbally abusive and harassing her. Law enforcement officers suggested she get a restraining order.

Winkleman had called 911 on several occasions. The second time, deputies came out but couldn’t find Davies and told her that they couldn’t take him to jail because he wasn’t hurting anyone and was allowed to destroy his own property. They suggested she text Davies and say, “Do not call me. Do not text. Do not harass me. Otherwise I will block your number.”

On her third 911 call, Winkleman explained that the family needed deputies to take Davies into custody and transport him for a 72-hour mental health evaluation, but officers didn’t come out. Instead, a deputy called her back and asked her if she had sent Davies the text.

“I told him that I had told and texted Joshua many times before that I was not going to accept his contact anymore because he was always threatening to hurt me or himself, but he ignores me and continues to try to reach me,” she says.

Winkleman’s fourth 911 call brought a deputy to her house the day Davies killed himself. The deputy had been part of the SWAT unit on the first 911 call to the house.

“I explained to him that Joshua was lying to the police psychologist and everyone else that ever came out before and that things were getting worse and Joshua was acting a lot different – much more scarier and out of control,” she says.

But she says the deputy wouldn’t take him in “because it would be like taking Joshua’s freedom away against his wishes.”

Ashleigh Allison says she was helping her brother move some of his belongings to her house later that day when she noticed he had a handgun in the front pocket of his black gym shorts.

“Josh, why do you have your pistol on you?” she asked.

“What’s going to happen is we’re going to go back to your house, and you’re going to call 911 and tell them that I broke the window of my girlfriend’s truck,” Davies replied. “They’re going to come, and I’m going to pull this out, and they’re going to shoot me so I don’t have to shoot myself.”

“They’re going to come, and I’m going to pull this out, and they’re going to shoot me so I don’t have to shoot myself.” – Joshua Davies

According to the police report, Winkleman “stated as usual she was advised there was nothing that could be done” when the deputy visited her home earlier that day.

When Ashleigh Allison called 911, she slipped outside to tell the dispatcher about her brother’s plan.

“He’s been very depressed and going about his life,” she said.

“What did he say about wanting police to come out?” the dispatcher asked again.

“He wanted me to call 911. … I’m sorry,” she replied. “He’s coming over here.”

Davies followed his sister outside and told her to hang up the phone, but she told him she wouldn’t. She began to tell the dispatcher what her brother had said but stopped midsentence, saying her brother’s name when she noticed that he had pointed the gun at his head.

Then he pulled the trigger on her front porch. The gunshot sounds like a faint echo in the 911 recording.

“He was gone,” Ashleigh Allison says. “It was, like, not him.”

Her mother compares it to demonic possession.

“It was evil, maniacal, almost like a strategic takeover of his being and his soul,” she says. “I saw this darkness take over every aspect of his life. It wasn’t always dark. He would have these days where things would seem OK, but brewing inside of him was something completely different.”

Six months have passed since Davies killed himself. Leigh Allison holds the Denton County Sheriff’s Office responsible for her son’s death because they wouldn’t help him when his family begged them. She called the deputies “murderers” when they tried to console her at the scene. She says she wants to hold them financially responsible, but she’s struggling to find an attorney willing to sue the county.

“I was talking to my son, dealing with him every day, and trying to give him hope and keep him from killing himself and destroying more property,” she says. “I was wanting to have an intervention. And the way the laws are set up, you can’t even compel someone to go to a 72-hour examination.

“I don’t know why they were always so quick to file charges on him,” she adds. “Every time that I called or his girlfriend called, we always said the same thing: ‘We want you to come out and take him … for the 72-hour evaluation because we feel that he is a threat to himself. We did the same script every time, but they would always say the same thing: ‘He doesn’t want to go, but we’ll arrest him if you want us to.'”

Joshua Davies as a boy

Brian Maschino

Winkleman is still working and trying to provide for their daughter, who will only know him in pictures. “I am still so hurt,” she says.

Ashleigh Allison credits Denton County MHMR’s Local Outreach to Suicide Survivors, known as the LOSS Team, which counsels families of suicide victims, and trauma counselors for helping her deal with her experience. She has post traumatic stress disorder and uses a service dog for cognitive behavioral therapy.

“For me, it’s always in the back of my head,” she says. “I don’t think I have a moment where it’s not somewhere in my brain.”

His death is why she became a trained counselor for a crisis text line. She wants to help other people in similar situations.

“He was too ashamed to get help,” she says. “A lot of people feel that way, but it’s OK to feel helpless.”