khraish khraish

Audio By Carbonatix

A child born to a place like this in West Dallas may also be born to a universe of despair.

khraish khraish

We got stuck on the wrong part of what the police chief said. At a press conference Jan. 5 about the shooting death that day in Dallas of a 1-year-old and the nonfatal shootings of an 8-year-old and a 20-year-old, Dallas Police Chief U. Renee Hall used a curse word. Tell you later.

The part we need to hear is what came just before the swear word. Hall said she had visited the murder scene, where a sleeping child, Rory Norman, was shot through a bedroom window with a rifle. A 20-year-old uncle was shot multiple times in the same attack but not killed. It’s safe to assume the murder scene was bloody.

Hall, seeming almost distant from the press conference for a moment, said, “It’s the scene. It’s the scene of a baby dying. I don’t know what that looks like to anyone else. But I know it’s something that you never want to see.”

I had this odd flash. For whatever reason, I remembered a memoir I read a long time ago by Martha Gellhorn, a pioneering war correspondent who covered the run-up to World War II. She wrote, “When I saw the starved withered babies in the Barcelona Children’s Hospital and the eyes of the silent wounded children, I decided to get out. Leave Europe, leave history.” (She didn’t. She came back and covered the war.)

This is what struck me and why I thought of Gellhorn when I watched Hall speak. And, please, go ahead and flail me and call me every name in the book for being a sexist gender-generalizing idiot. I’m good with that.

Not always and with many notable exceptions, women can be capable of seeing social violence, war and crime, gangs and drunk husbands, all of it, the mayhem and the damage, in a way that often eludes men. Women see the children.

“It’s the scene. It’s the scene of a baby dying.” — Renee Hall

Too often men stupidly don’t see the children or don’t see them until it’s too late. For a woman like Chief Hall or like Martha Gellhorn, the children are never an afterthought. There is nothing collateral about the children. The children are at the center of it, the center of everything.

If we can’t meet that one obligation to protect, feed, house, teach and, sure, if there is any time left over, love the children, then our presence on the planet is a waste and a horror.

Women tend to see that right away. Men either not so much or too late. That’s why I’m glad our chief is a woman. I’m glad she got so angry that she forgot herself and used a curse word. If more women were our leaders, we would get to the solutions faster.

And by the way, that’s not just sentimentality talking. The larger message Hall gave last Sunday was that crime is a community problem, not a police problem, and that it cannot be reduced or even contained by any approach that fails to address the whole community.

Hall’s view is buttressed and supported by a growing body of research linking violence and poverty to place, to family and to moral culture. But this also is the swamp, the place where we get into the real political stickiness. Is there a way even to talk about this stuff frankly and realistically without wandering clumsily over the line into straight-up victim-blaming and racism?

We spoke here at the first of the year about a paper published in 2019 called “Poverty and Place.” It quantifies the withering effect a bad neighborhood exerts on the entire life of a child sent there by the lottery of birth. I am currently reading another work, a book called Stuck in Place by Patrick Sharkey, based on exhaustive research that paints an even more devastating picture of the effects of place.

But talking about ghettos is trickier than we might suspect, and the first trap is the word itself. Is the word ghetto merely a derogatory white racist term for the black community, or does it describe something real?

The answer is in the history of American law and public policy setting out the geographical borders of black neighborhoods from which resources, public and private, were subsequently withheld. We’ve talked about that here, too.

The white community in Dallas was never a place on the map, exactly. It was wherever it wanted to be. But the black community had lines around it, lines drawn by white people, and those borders had powerful economic and social consequences.

So the ghetto is real. It was and still is an intentional creation and a physical place. The trick is in comprehending that the concept and the fact of the ghetto do not reflect pejoratively on black people. They reflect pejoratively on white people.

The next big trick is in understanding what the ghetto does to its inhabitants. The knee-jerk reaction of conservatives is to say that it’s up to a person born to a bad place in life to lift himself out of it. The knee-jerk reaction of a liberal like myself is to call that victim-blaming. Sharkey’s book uses solid empirical research to show that we’re all wrong and we’re all right.

No, it was not the fault of 1-year-old Rory Norman that he was born to a place that would see him executed by gunfire weeks before his second birthday. And, no, it is not the fault of a community deliberately and systematically starved over time of basic civic resources and economic activity that most of the people in it wind up being poorly educated and very poor.

But, yes, as Sharkey points out, people have to lift themselves up out of that place. And, yes, as families remain in the ghetto over multiple generations, the knowledge of how to get out and the will to get out may dwindle. A child born to the ghetto is not born only to a place but also to a multigenerational tradition of despair.

Somewhere in the city right now is the person who jammed a rifle into the window of the bedroom where Rory and his uncle were sleeping and squeezed off a magazine full of rounds. I suspect that person is young, probably male. I would hazard a guess that he was an early school dropout and has at least a minor criminal record, rendering him virtually unemployable.

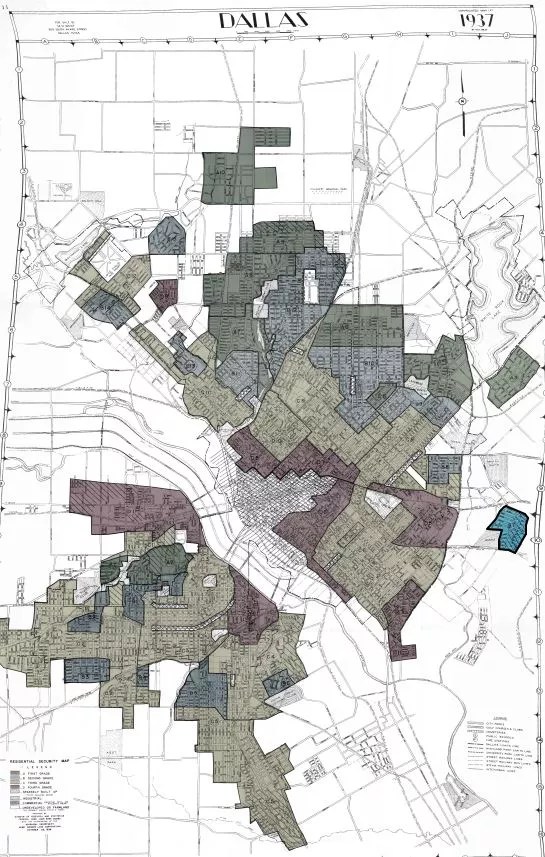

Redlining maps promulgated by the federal government in the 1930s, showing where investment in Dallas should be withheld, closely mirror the city’s poorest neighborhoods today.

University of Richmond

Sure, he did it all to himself. So what? The fact remains that he’s standing around a barrel fire on a vacant lot somewhere on these winter afternoons drinking and smoking, and not too far away is his buddy’s AR-15 or his own AK and a box full of cartridges.

Shit. That was the word the chief used. “This shit has to stop in this city,” she said.

“When I saw the starved withered babies in the Barcelona Children’s Hospital and the eyes of the silent wounded children, I decided to get out.” — Martha Gellhorn

Shit is what that guy who shot Rory thinks his own life is worth, and he always has. Shit. Chances are you will never cross his path. But you do live in the same city with him. And you do need to know, if you ever do confront him, that he thinks your life is worth shit, too. Shit. Because that’s what he thinks life itself is worth.

I haven’t finished Sharkey, but I have read enough to find myself stumbling on what seems like a contradiction. He begins by tying the deleterious effects of racism and segregation strongly to a geographical place, the ghetto. But then he introduces a concept he calls “residential context,” which seems to be something that can move around the map.

If some blunt force comes along and shovels all the people in the ghetto out of one place and dumps them in another, they will reproduce the same ghetto with the same values and problems in the new place. So it’s not the place. It’s not the soil.

It’s the people. The conservative onlooker, not inclined to spend a lot of time crying over other people’s spilled milk, may say to hell with them. They’re adults. They made their mess. Let them live with it. The liberal like me might say we made the mess, so we should leave them alone.

I think the leader like Renee Hall or the writer like Martha Gellhorn is not even looking at the adults first. She is looking at the children. Chief Hall, I suspect, is looking at the bloody mess where a beautiful, bumptious 1-year-old child lay sleeping hours before.

That child did nothing to deserve being born to despair, born to schools that wouldn’t teach him how to read, born to violence, drugs, a penal system that would teach him he’s a worthless piece of shit. He wasn’t born a piece of shit. He was born a baby, an innocent.

The anger in Hall’s voice and the grief in her glistening eyes should steer us all in the right direction. And it’s not about sending the cops out there with orders to fix everything for us.

We have to fix it. We need to look at Rory Norman as our own child. We must look at all of the children born to poverty and racial segregation in our city as our shared responsibility. We have to do everything and anything we can to reduce human despair in our city. We must look at despair as a social cancer that can only metastasize.

Why would we ever want a single newborn baby, anybody’s baby, to be born to despair if we could help it? Why would we allow tens of thousands of babies to be born to it? We have to change their world, not because of whose fault it is, not even for self-protection, but because these are children. Hall gets that. And we should all agree. This shit does have to stop.