U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement

Audio By Carbonatix

The first round of Wednesday afternoon immigration court hearings is about to start when Noemi Rios tracks down the ICE agents.

Four men – some in masks, some in baseball caps emblazoned with the American flag – lean nonchalantly against a wall in the gray hallway on the 10th floor of the Earle Cabell Federal Building in downtown Dallas. They do not wear badges or vests that identify them as law enforcement agents, but as Rios rounds the hallway’s corner, they shift as if on instinct so that their backs are turned to her.

Rios pulls a large notepad out of her bag and flips it open. On the page, “Ellos Son Migra” is written in bright blue marker. A blue arrow points toward the men whose eyes are trained on the doors of courtrooms.

The sign warns, “They Are ICE.” The eyes of women carrying manila folders and men holding babies widen each time they see the warning and walk past Rios to file into their hearings.

A Vecinos Unidos volunteer (left) is ignored while attempting to speak with ICE agents.

Emma Ruby

Rios has volunteered as a court observer at Dallas’ federal immigration court for five months. In that time, she’s come to recognize the men and women who position themselves in the hallways and occasionally haul away a man or woman after their hearing has ended. On her phone, she swipes through photos of men being wrestled to the floor in the courts’ hallways, and points between agents in the pictures and the men now standing on the other side of the hallway.

After a few minutes, she notices two men have angled their phones to point in our direction. Rios throws up a peace sign for what are presumably photos being taken.

Earlier this summer, the technology publication 404 Media published an investigation that found the Immigration and Customs Enforcement agency was rolling out a mobile app called Mobile Fortify for field officers. The app provides facial recognition services by cross-referencing a smartphone photo with government databases.

Around the same time that the investigation was published, Rios, standing alone, was approached by an agent who said, “Hey, Noemi,” before walking away.

“They’ll call you by your name, so that you know they know who you are,” Rios says.

Since then, she’s stopped coming to court by herself, she said. But her effort to be the eyes and assistance for Dallas’ increasingly vulnerable immigrant community has only ramped up.

“I was scared [when I realized ICE knows who I am]. These are lawless individuals,” she said. “But we don’t allow fear to paralyze us. We have an obligation.”

Vecinos Unidos

It was March when, frustrated by the political climate and President Donald Trump’s hardline immigration policies, Rios stepped away from her corporate job for a six-month sabbatical.

She reached out to a few activist friends she’d made during the “first presidency,” and asked where she was needed. They told her they were worried about what was coming down the line for immigration courts, and that Dallas needed someone to get an immigration court watcher program off the ground.

“They said, based on their expertise, that things were probably going to get pretty scary pretty quick,” she said.

March was a crash course in the immigration legal system. Rios took the American Bar Association’s court-watching course and brushed up on the intricacies of the immigration process. With the help of a few other activists, she launched the group Vecinos Unidos – Neighbors United – to coordinate information and volunteers.

She began familiarizing herself with the courts in April, and for a few weeks, everything seemed to match the experience her legal research had outlined. She was allowed into courtrooms during the first round of hearings and helped families navigate a system that doesn’t seem to accommodate non-English speakers.

A small group of volunteers took over roles like courtroom monitors, who watch as proceedings unfold, and waiting room monitors, who come supplied with grocery bags full of coloring books, crayons and stickers for the children who sit and wait. Hall monitors spend shifts taking notes and documenting from the court’s entrance; photos aren’t allowed inside the courtrooms or waiting areas.

Bilingual volunteers act as navigation support. While the bulk of the immigration courtrooms are located on the 10th floor, three are on the fourth floor. The floors are serviced by different elevators, so if your hearing is moved, you have to return to the building’s lobby and find the other elevators to get to the proper courtroom. It’s a simple enough task, as long as you can read the signage posted throughout the building.

While Rios has experience with activism, she thinks it’s important that she and the other volunteers remember that what they are doing in Dallas’ immigration court “is not a demonstration.” The public has a right to court access, and Rios’ strategy seems to be of the “use it or lose it” mentality.

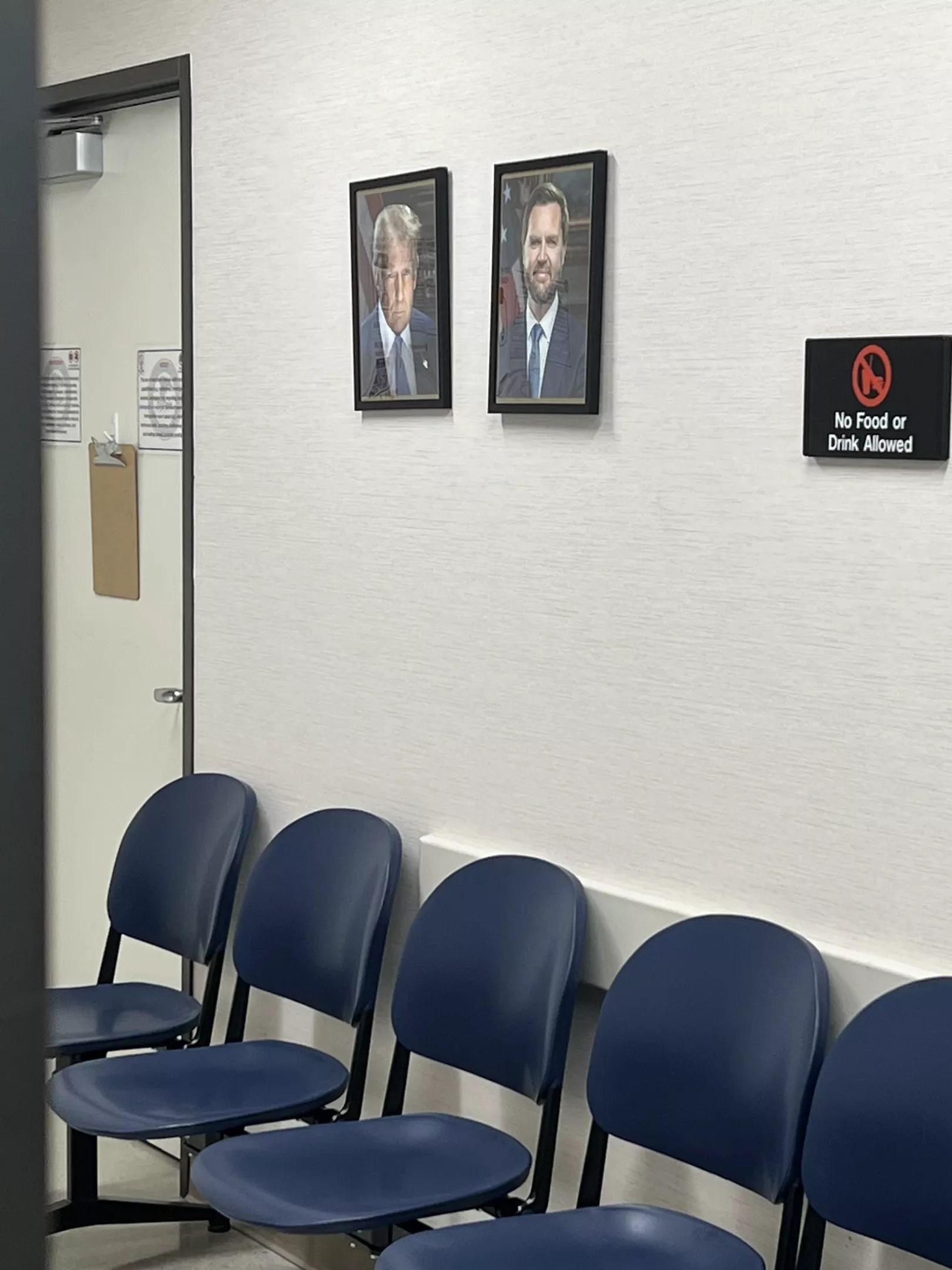

Volunteers began to notice framed images of the president and vice president being posted around Dallas federal immigration courtrooms earlier this month.

Emma Ruby

Already, they’ve noticed changes “judge by judge” in how often they are let into the courtrooms. Recently, she’s even noticed some judges barring spouses from attending the hearings. (Later in the day, Rios questions the legality of this in a conversation with a court administrator, who tells her “a lot of factors” determine whether a judge wants to let someone into a courtroom.)

“My summer was spent figuring this all out, understanding it, and putting an orientation together and recruiting,” Rios said. “Unless it’s necessary, we really pick our battles. … We’re not protesting here.”

On Wednesday afternoon, a frantic volunteer darts between floors, attempting to help a Spanish-speaking woman who’d received a notice about a 2 p.m. court hearing on the fourth floor. The woman arrived an hour early, wearing a white lace blouse with her long hair brushed neatly down her back, and sat beside her son, who she brought to translate. In the gray waiting room, her seat was positioned beneath a framed image of a grimacing Donald Trump. Despite the letter in her hand, the woman’s name wasn’t posted to the courtroom list.

The son pulls aside a Vecinos Unidos volunteer who, after checking the 10th floor’s court listing, realizes that the woman’s hearing had been moved to 12:30 p.m. upstairs. She was now late, by no fault of her own.

“Most people get a letter in the mail that only has the building number on it. How are you supposed to find your way?” says Rios, as the volunteer ushers the English-speaking son towards a court scheduler, urging him to present his mother’s letter that showed a 2 p.m. hearing time. “Most come with no accompaniment, with no legal support. … And if you’re late, even by a few minutes, if you aren’t here when they call your name and shut the court door, you can get deportation orders.”

In recent months, Vecinos Unidos has begun assembling resources for family preparedness training. The training addresses the “worst-case scenario” for families. Undocumented individuals who could potentially face deportation are walked through questions like, “If you are detained, who is authorized to pick your children up from school? Who can see their medical records? What bills need to be turned off, and what are the passwords for those accounts?”

It’s a process not dissimilar to the preparations taken when a person is expected to die.

Through the Double Doors

The halls are quiet when a security guard approaches Rios, still holding her sign. He nods his approval at where she stands – earlier in the day, he’d ushered her out of the section of the hallway where immigration court turns to Internal Revenue Service offices. Evidently, the majority of complaints made about Rios and her gaggle of volunteers come from the IRS.

“You told me I couldn’t stand here last week,” she shoots back.

“Noemi, stop being contrary,” he sighs before moving along.

This was where she stood last Thursday when the guard asked her and her fellow volunteers to move to a different section of the floor. “Minutes” after they did, a handful of ICE agents came out from the swinging double doors that are in the hallway’s center to apprehend a man whose hearing had just ended. Rios is still reeling from the experience.

“We could hear him screaming [for help] all the way down [the stairs],” Rios said.

After five months of attending court for a few hours two or three times a week, Rios has seen ICE agents arrest six people. Other volunteers have documented a handful of other detainments during other shifts.

Noemi Rios stands outside of Dallas’ federal immigration court on Wednesday, Aug. 20, with a sign warning Spanish-speakers that ICE agents are present.

Emma Ruby

In videos taken by hall monitors, volunteers can be heard yelling to those detained, “What’s your A-number? What’s your name? Who can we call?”

An A-number, or alien number, is the unique code assigned to a person going through the United States’ immigration process. It can be used to identify them in databases like detention center searches.

Often, volunteers’ calls aren’t successful. “There’s a lot happening” the moment a person is detained, Rios said. Everyone is pumped up on adrenaline. But in a handful of cases, Vecinos Unidos has been able to determine a detainee’s identity and notify their family that they won’t be coming home that night.

At 2 p.m., as the first round of hearings concludes, Rios and a handful of other volunteers begin to document agents moving in their group chat on Signal, a messaging app known for its privacy and security. The four men standing in the same hallway as us have disappeared through the double doors one by one, and two other agents walk through the waiting rooms, towards the elevators, through the maze of gray halls with gray doors that reveal nothing, until Rios has lost track of them.

This is what it looks like, Rios said, when they are getting ready to take someone.

“My heart is pounding,” she whispers.

One agent stands in front of the elevators as a family with four children approaches, and Rios positions herself so the family is in her eyesight – as if by watching, she can keep them from being detained. When the elevator doors close, she breathes a sigh of relief. The agent turns and walks through another set of unmarked doors.

Photographs are no longer allowed in the immigration courtroom once the floor turns to linoleum.

Emma Ruby

By 2:45 p.m., the court is nearly empty, the day’s hearings concluded. Volunteers on the fourth floor give the all clear. Two more laps around the 10th floor, and Rios is convinced that ICE has gone. No arrests for the day.

A girl who looks to be around 20 is the last to leave the court. She asks Rios in Spanish how to get to the elevator. Rios points her down the hall and asks if her hearing went well. The girl nods, “Yes,” and smiles.

For every time Rios has witnessed the worst moment of a person’s life unfold in the hallways of immigration court, she’s seen good moments, too.

“Felicidades, felicidades!” Rios calls as the woman walks away. Congratulations, congratulations.

Next week, Rios returns to work.

She hopes to still make it to court to observe when she can, but ultimately, she has to trust that her dedication to recruitment and training efforts has paid off. She’s spoken in churches of nearly every denomination, activist meetings and impromptu gatherings about the need for more volunteers and more eyes on the immigration courts and the importance of officials knowing they’re being watched.

She has to figure out how one returns to normalcy after six months of this. She’s been struggling with survivor’s guilt: the feeling that, as a Latina woman, it was nothing more than luck that she was born in the United States.

“I’ve had to get comfortable with the feeling of my heart beating in my throat,” she said.