Illustration by Alex Nabaum

Audio By Carbonatix

The bruising around Candra Rogers’ right eye hadn’t completely faded by the time she addressed the media in a Corsicana ISD boardroom on Aug. 27.

Twelve days earlier, the Collins Intermediate School Assistant Principal had responded to a radio call for assistance from a behavioral teacher. When Rogers approached the classroom, the teacher, who was reportedly assaulted by a student who remained in the room, stood outside with some students. Rogers entered the classroom alone and found an “irate” student surrounded by a “ransacked” room.

As another administrator entered the classroom behind Rogers, the student began throwing chairs at her. She caught one and used it to block the others, but when the student picked up a wooden hanger she was unable to react in time.

“The hanger hit me in my right eye and knocked it out of the socket,” Rogers told the media. “I grabbed my face while blood was pouring out of my head and stumbled out of the classroom door.”

When news happens, Dallas Observer is there —

Your support strengthens our coverage.

We’re aiming to raise $30,000 by December 31, so we can continue covering what matters most to you. If the Dallas Observer matters to you, please take action and contribute today, so when news happens, our reporters can be there.

Rogers was airlifted to Parkland Medical Center and underwent surgery. Doctors were able to reinsert her eye, but her sight remains lost, and doctors believe Rogers’ eye may eventually have to be removed. The student was released to his parents and banned from returning to campus.

Less than two weeks after the assault, Rogers sat, surrounded by family, and sounded the alarm on a growing trend of violence and aggression in schools that advocates are concerned is increasingly targeted against educators.

“Our safety is important, too,” Rogers said. “We should not fear being in the classroom with an aggressive student.”

The rate of disciplinary infractions taking place on school campuses across North Texas has spiked in the years since the COVID-19 pandemic, data provided to the Observer shows.

In Plano ISD, 70 assaults were committed by students against school employees during the 2023-24 school year, compared to just 24 in the 2018-19 school year. On-campus assaults against other students rose to 168 in the last school year, whereas the years leading up to COVID-19 saw numbers in the 30s. Plano ISD provided the number of recorded incidents for 13 types of disciplinary infractions to the Observer – incidents like assaults, drug possession, weapons possession and robbery – over six school years beginning in 2018.

Every infraction increased in the years following the COVID-19 pandemic. The number of disciplinary infractions committed by Plano ISD students in the 2018-19 school year increased by 140% by the 2023-24 school year.

Dallas ISD recorded 653 on-campus assaults in 2023-24, just slightly less than the 662 in the prior school year. In the school years leading up to COVID-19, that number was in the 380s.

A malware attack against Fort Worth ISD in 2020 resulted in the district losing its pre-COVID data. The information provided to the Observer did not distinguish between specific types of incidents. Instead, a yearly total that encompasses all infraction types was submitted. In 2023-24, the district reported 653 behavioral incidents.

Only two years prior, that number was 329.

According to state data, there were fewer enrolled students in each of the three districts in the 2022-23 school year than in the 2018-19 school year.

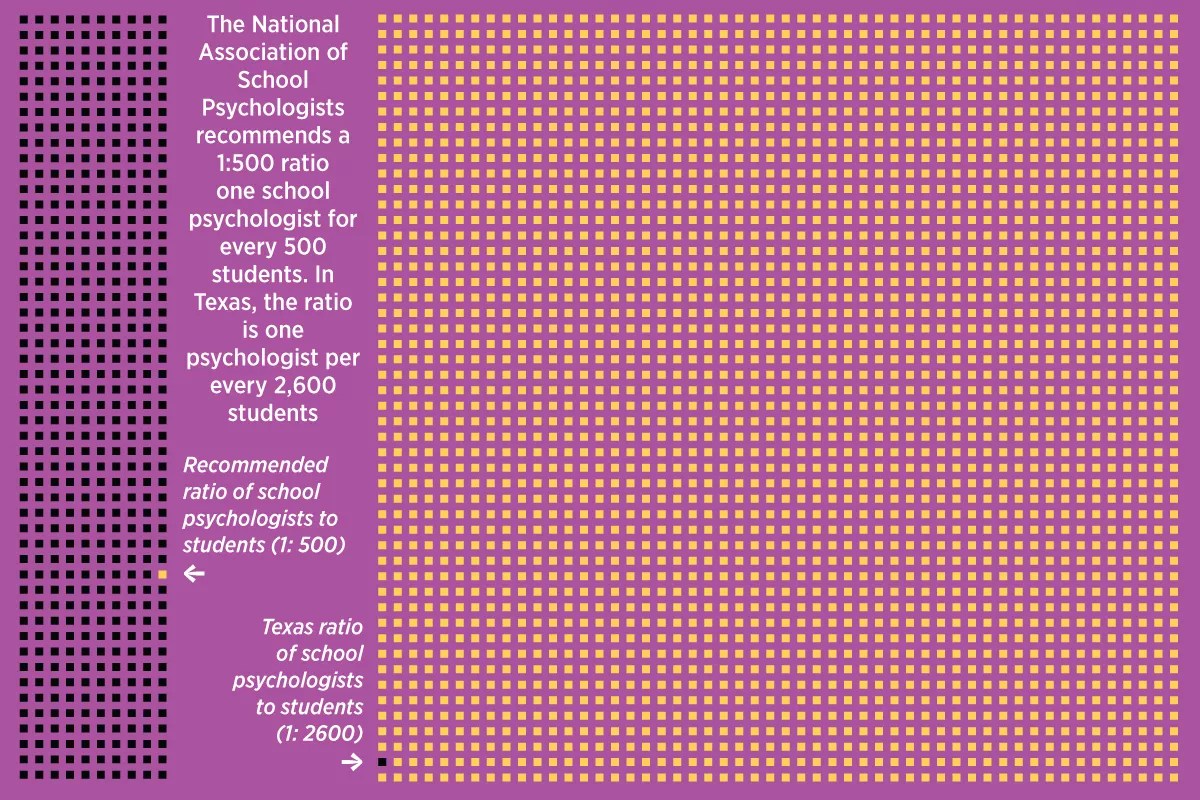

graphic by Sarah Schumacher

“If you talk to teachers long enough, they’re going to tell you that right now discipline is one of the leading concerns in their profession. Student behaviors are going unchecked, and they’re escalating to a point where a lot of them are becoming violent,” said Stephen Poole, director of the United Educators Association.

Throughout the country, schools at all age levels and demographics are enduring spikes in behavioral challenges, he added. Prior to the pandemic, 65% of teachers reported experiencing at least one instance of verbal harassment or threatening behavior by a student, research by the American Psychological Association shows. In 2024, that number has risen to 80%. The same study reports that teachers are experiencing more physical attacks by both students and parents than they did pre-pandemic.

Poole, whose organization represents teachers across 46 school districts in North Texas, said the number of teachers who tell him they are concerned about discipline in schools “grows every day.” And for many of them, it’s becoming a dealbreaker.

“I just talked to a teacher yesterday who is eligible for retirement,” Poole said. “She didn’t think she was going to retire for a couple more years, but she just can’t take another day of what she’s been experiencing in the classroom.”

A Mental Health Crisis Culminating in the Classroom

Sandy Kramer, who has taught in Fort Worth ISD for decades, had never before witnessed anything like last year’s graduating class. The group of students began their high school education on Zoom because of the pandemic, missing out on the socialization that comes with transitioning from middle school to high school.

“Last year’s graduating class was the most broken group of students I’ve ever seen,” Kramer, whose name has been changed because of her current employment with the district, said. “They were unfocused and anxious. The overriding sense I got was that they were anxious about a lot of things.”

The country is experiencing an adolescent mental health crisis that began years before the pandemic, data from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention shows. But social isolation, unpredictable academic interruptions and the unprecedented amount of lives lost during the height of the pandemic could have compounded the persistent feelings of sadness and hopelessness that almost half of all teens surveyed reported experiencing in 2021, says Dr. Carol Tamminga, a psychiatrist with the Texas Children’s Mental Health Care Consortium. The 86th Texas Legislature created the consortium in an effort to combat the state’s adolescent mental health crisis.

Even younger children, especially those who were fully isolated throughout the pandemic, began presenting to doctors with increased rates of anxiety and depression in the years after lockdown, she says. As with most conditions, mental health illnesses present differently in children than they do in adults. The resulting behavior often lines up with the outbursts that educators are pointing to as problematic, Tamminga added.

“Children may not be able to articulate [exactly what they’re feeling] so they may present as being fussy,” Tamminga said. “[The pandemic] was really quite severe, and children don’t really know how to say, ‘I’m feeling severely depressed.’ So they would have behavioral disorders or they would have what people might call acting out.”

In 2022, Tamminga noted a shift in the statewide discourse surrounding adolescent mental health after the Robb Elementary School mass shooting in Uvalde, Texas. Nineteen students and two teachers were killed by a local teen who, prior to the shooting, had expressed suicidal ideation and violent tendencies – behaviors that should have been obvious red flags to each of the adults in his life, noted a state investigative report released months after the shooting.

But in less extreme cases, Tamminga recognizes that schools often lack the resources to handle behavioral challenges or track red flags on their own, especially those caused by a mental illness. Schools are facing a severe shortage in mental health professionals; CBS News reported that, as of 2023, Texas had one school psychologist for every 2,600 students. The National Association of School Psychologists recommends a 1:500 ratio.

The American School Counselors Association recommends one school counselor for every 250 students, but in Texas, there’s only one counselor for every 390 students. And it’s difficult to imagine that a single social worker for every 5,200 Texas students is able to play an effective role in curbing behavioral challenges.

Funding for the consortium was increased in 2023 as part of the Legislature’s $11.6-billion grant to behavioral health initiatives. The funding, in part, helped strengthen the Texas Child Health Access Through Telemedicine program, which connects K-12 schools across the state with licensed mental health professionals who can help guide care for youth in crisis. The program also allows school administrators to flag warning signs or request assistance for youth presenting violent or harmful ideations, Tamminga said. All of it is done on the state’s dime.

Continuing investments in adolescent mental health is a move that legislators, education advocates and psychiatric experts hope will have a positive impact on student behavior in the school environment, but solving the problem could take more than just state dollars.

Doing It for the Kids

Kramer has not experienced students escalating to defiance or violence in her own classroom, but she believes her school’s culture has been negatively impacted in recent years by poor staff retention, an issue being felt across Fort Worth ISD. Last year, Fort Worth ISD experienced more administrative resignations than any year since 2017, the Fort Worth Report found. That turnover in staff is adding to the instability students are experiencing during their education, Kramer said.

Last winter, hostile student behaviors at a DeSoto Middle School resulted in 30 educators calling out of work in protest.

The pandemic didn’t only “break” students, she added. Over 13% of Texas teachers left the profession in the 2022-23 school year, state data shows. The trauma of the pandemic, along with a shift in the public’s perception of education, is something she is still reckoning with.

“I’m still not recovered from what happened and the way that teachers were treated by the public. There was all this ‘Y’all are heroes, yay yay yay,’ and then it turned to ‘Y’all are grooming our students,'” she said. “It was just really a roller coaster of a time frame, and it’s still rippling out.”

With schools understaffed, teachers are in the perilous position of balancing their passion for education with their own mental health. Data shows that this isn’t just a North Texas issue; student behavioral issues are making it difficult for teachers to keep “doing it for the kids” nationwide.

In Delaware, a survey conducted by Emma White Research revealed that three in five educators now believe that they will retire early or leave public education because of student behavioral challenges. One in five reported being physically hurt by a student, and two in five reported having had to evacuate their classrooms due to unsafe student behaviors. In a statement, Delaware State Education Association President Stephanie Ingram described the state of public education as reaching “a crisis point.”

In Colorado, staffing shortages have doubled in the years since the pandemic, and out-of-school suspensions given out to unruly students have increased by 25%. Schools in New York City are seeing increases in disciplinary issues similar to those recorded by North Texas districts.

“[Through the pandemic] teachers and schools were preaching grace. ‘Provide grace to the students. They’ve gone through unprecedented times,'” Poole said. “But a lot of administrators have taken a hands-off approach when it comes to student discipline and they just leave it all on the teachers in the classroom. And unfortunately, we’re seeing a very sharp increase in [negative] student behaviors, including fights and assaults on campus.”

Student discipline is generally left to the discretion of districts or schools to regulate. At Kramer’s school, educators are told to notify administrators immediately in the case of violent offenses. Everything else is left to the teachers, who are often required to use instructional time to keep track of which student is on which strike for which infraction.

A set of guidelines prescribed by administrators outlines the levels of escalation when handling discipline: first offense, speak with the child; second offense, call the parents; third offense, go to administrators. In “reality,” though, Kramer says she is handling things entirely on her own.

“I’ve been conditioned not to [go to the administration about student behavioral issues] because when I send it to them, nothing happens,” Kramer said. “I don’t see the point in putting myself through all that.”

State guidelines for districts’ codes of conduct are outlined in Chapter 37 of the Texas Education Code. Adopted by the state in 1995, the code includes some broad language that allows districts to define their own policies. It also gives specific examples of cases where students should be removed from school, a measure reserved for the worst of the worst offenses, such as “engaging in conduct punishable as a felony.”

In the mid-’90s, those policies (known as “zero-tolerance policies”) that called for the immediate removal of students from the school environment as punishment for behavior – regardless of context or whether the student had prior behavioral infractions – were widespread across Texas districts. The state has made some tweaks that offer some student protections from discipline; for instance, a homeless student cannot be given out-of-school suspension as a punishment.

Across many Texas districts, the zero-tolerance discipline style lost traction through the 2000s as studies found they were used disproportionately against Black male students, and often made no consideration for nuances such as self-defense. In 2017, Dallas ISD eliminated out-of-school suspensions for kindergarten through second-grade students – with exceptions for extreme cases, such as bringing a weapon to campus – as part of the effort to move away from the “antiquated discipline system,” the district said. State law followed Dallas ISD’s lead later the same year.

As zero-tolerance policies slipped in popularity, more kids were able to stay in the classroom, but Poole is concerned that some North Texas districts are removing too many student discipline tools without solving the “underlying behaviors” that lead to disciplinary action being necessary in the first place.

“That’s where schools are caught in a Catch-22,” Poole said. “School district policy has tied [teacher’s] hands, but nothing has been given to them to help provide support to address the student behaviors, especially before they escalate to violence. And so our schools are suffering, our classes are suffering.”

He worries the result will be more teachers burning out and leaving the profession for good, and more parents pulling their children out of public schools in favor of a private or charter education.

Inviting Nuance Into School Discipline

In 2023, zero-tolerance language was reintroduced into the state’s education policy through a mandate requiring that students caught with a vape device be sent to their district’s disciplinary alternative education program, or DAEP. Advocates for education justice criticized the law, House Bill 114, as being a step backward in Texas’ approach to student discipline.

A report by The Dallas Morning News found that across eight Dallas-area school districts, one in five students sent to an alternative program during the last school year was there because of vaping.

“The problem is that everyone equates cracking down with kicking kids out [of school], but there are other forms of accountability,” Renuka Rege, senior staff attorney with the Education Justice Project at Texas Appleseed, said. “We had behavioral issues before the pandemic, we’ve always had them. And we had zero-tolerance policies, what we call exclusionary discipline. … We found that they didn’t work. They didn’t reduce behavior issues back then. They only disengaged and pushed kids out of their education.”

Outside of state mandates like H.B. 114, districts are mostly on their own to determine how student discipline should be handled.

For Dallas ISD, the years leading up to the pandemic marked a shift towards exploring alternative discipline styles. Just ten years ago, 12,000 students each school year received an out-of-school suspension, state data shows. In 2021, Dallas ISD ended out-of-school suspensions for middle and high school students.

As an alternative, the district introduced “reset centers” into its secondary school campuses. The centers, led by coordinators with experience in adolescent behavior, are a place for students to “cool off” when problems arise, says Rena Honea, who represents Dallas ISD’s non-administrative employees with Alliance/AFT.

“Kids pop off all the time, they’ll say whatever comes to their minds. The state has taken away a lot of the discipline that was allowed years ago and so districts are having to be pretty creative in how they handle this type of behavior,” Honea said. “[The reset centers give students] coping skills and allow them to continue to work on their schoolwork, while de-escalating so they are able to rejoin the classroom.”

Dallas ISD has heralded the success of reset centers, stating that more kids are spending more time in the classroom and habitual infractions have decreased since the reset centers were implemented. The program is on par with the nuanced approach to student discipline that Rege advocates. She urges schools to consider weaving “learning moments” into fair and equitable consequences when students misbehave instead of removing the child from class. Students who engage in a physical fight would write essays on conflict resolution; children who regularly disrupt class would meet with a trusted adult to talk about their compulsive feelings.

The question is, with the burden placed on educators’ shoulders already growing with each school year, and teachers like Kramer who say they have been left to handle behavior on their own, is Rege’s approach a realistic one?

Ideally, Rege said, schools would work to fill as many mental health-related roles each year, creating a robust team of professionals skilled in adolescent behaviors tasked with handling discipline for the entire student body. She recognizes that districts are “strapped,” however, making hiring unfeasible for many.

Unfunded state mandates are further exacerbating already taut district budgets, and state laws passed in the name of school safety – a topic intrinsically connected to student discipline – are often reactionary, placing more burdens on schools in an effort to curb tragedies, Rege said. In 2018, after school shootings in Texas and Florida, Gov. Greg Abbott introduced a school safety plan that proposed, among other things, widening the list of behaviors that warrant out-of-school suspension.

The plan was not enacted, but the following year “behavioral threat assessments,” which schools fill out to identify students who may be exhibiting violent or problematic behaviors, were introduced. In response to the Uvalde mass shooting, lawmakers passed an unfunded mandate that requires the hiring of an armed officer at every school in the state. Staffing challenges and funding deficits have left many districts, including Dallas ISD, struggling to comply.

At worst, the laws criminalize minors. Some school districts “overcorrect” in the months after a tragedy, Rege said, and the result can be “very damaging” to the future of a child who may not be old enough to fully understand what they said or posted online. Since the September shooting at a high school in Georgia, an “increasing” number of Texas students, some as young as 10 years old, have been flagged by schools for making a terroristic threat, a felony charge, she said.

At best, Rege added, these mandates are a misappropriation of resources that school districts badly need to handle disciplinary issues in a more equitable way.

“More officers with more guns, unfortunately, does not prevent these things from happening. So we are misdirecting our resources towards a solution that’s very expensive and not useful,” Rege said. “Therefore, there is no money left for the supportive staff that actually talk with kids [who are having discipline issues] and find out what problems they’re having and help them come up with solutions. Those are the people that we really need, and that’s what we really should be spending our money on.”

Boats Against the Current

Despite the state legislature’s past interest in funding adolescent mental health initiatives and school safety mandates, school vouchers are likely to be the star of the upcoming legislative session. Education advocates warn that school vouchers – an initiative Abbott is “certain” will be passed in the next session – will siphon more money away from public school districts.

As she addressed the media, Rogers voiced a frustration she shares with many educators over the state’s underfunding of public schools. Stoic, she described struggles with student discipline and teacher retention as “the collateral damage of Governor Abbott’s choices.”

“When schools are underfunded, all stakeholders suffer,” Rogers said. “I have been in education for 30 years and I am a proud product of public schools. I believe in public school education, but what happened to me should never happen to another educator.”

Rogers’ decision to come forward about her experience was an uncommon one. Educators are generally one of the most difficult groups to speak with on the record. Most districts implement policies prohibiting media interviews, and recent public attacks on teachers make most hesitate to be named.

For this story, the Observer reached out to eight North Texas educators who had voiced frustration with student behaviors over public social media posts. Only one agreed to speak on the record. Educators are often “afraid what would happen to them” if they do not speak about their “classrooms in a positive way,” Honea said.

“[Teaching is] so important and getting more important. The ability of people to be persuaded by disinformation is terrifying to me right now,” Kramer said. “And the only solution to that is education. I think that’s going to save the world.”