Illustration by Sarah Schumacher

Audio By Carbonatix

In an idyllic paradise, palm fronds cast shadows on glimmering water. Nearby, the rhythmic droning of Tibetan singing bowls is interrupted by the chirps of the black-throated magpie-jays hiding high up in the trees. Volcanic rocks glow like rubies in the hearth of a temazcal, a traditional Mesoamerican sweat lodge. The lingering scents of chef-curated tasting menus waft through the open halls of a sprawling hacienda. Beneath the terracotta roof tiles that glow in the Mexican sun, motionless bodies in near-catatonic states lie lined up under the eyes of physicians overseeing their hours-long hallucinogenic trip.

Weekly, throngs of people touch down in Mexico for a getaway that isn’t the usual tropical vacation. Some meet a suited chauffeur ready to cart them in a swanky, leather-finished Cadillac to a luxury resort-style facility in Cancun or Tulum. Others, less fortunate, haphazardly work through a language barrier with an Uber driver taking them to a seedy center in Tijuana, just miles from the American border, or Tezpotlan, a small town in the mountain region two hours south of Mexico City. All arrive in the country with the same goal: to be rid of their ailments, whether it be a rehab-resistant opioid addiction, the unshakeable traumas of war service or the tremors that come with neurodegenerative diseases. To do so, they’ve turned to a holistic medical treatment available in only a handful of countries, and certainly not the United States.

Ibogaine, pronounced eye-bow-gain, is a psychoactive alkaloid extracted from the root bark of iboga, an evergreen shrub native to Central Africa. Forest-dwelling tribes in Gabon have used the bitter powdered root for thousands of years in a sacred ritual symbolizing death and rebirth as part of Bwiti, a spiritual practice in the region. Ingesting the root, which induces a half-day-long immobilizing high, paired with an occasionally fatal racing heart rate, is part of the initiation ceremony into the Bwiti practice. The ceremony is said to be as close to a kiss of death as a human can get before crossing the Pearly Gates.

In 1992, the Drug Enforcement Administration formally classified ibogaine as a Schedule I substance, ending ongoing research in the U.S. and creating significant barriers for future research. Since then, no one has gained permission to distribute ibogaine for clinical trials on U.S. soil, but Texas, an unlikely proponent, successfully passed a bill during this year’s legislative session that creates a $100 million grant program, of which the state will provide half, for ibogaine clinical research, pending approval from the Food and Drug Administration. It is the largest publicly funded psychedelic research initiative in history.

Will you step up to support Dallas Observer this year?

We’re aiming to raise $30,000 by December 31, so we can continue covering what matters most to you. If the Dallas Observer matters to you, please take action and contribute today, so when news happens, our reporters can be there.

The bipartisan bill, which GOP leaders heavily backed, stands in juxtaposition to the resurrection of the War on Drugs raging in Texas right now. In a state inching closer to an outright ban on all THC products, ibogaine, one of the most potent hallucinogens with a proven high risk of fatality when not properly administered, has passed staunch conservative drug naysayers. They are attracted by the drug’s potential applications to alleviate the opioid crisis and deal with a shortage of mental health services for veterans. As a bonus, the state will reap the earliest economic boosts when the days of ibogaine commercialization arrive. But critics point out the hypocrisy of removing veterans’ access to widely used THC products while simultaneously touting a cost-prohibitive therapy that is years from widespread use in an incompatible healthcare system.

Ambio Life Sciences is a rehabilitation clinic that uses Ibogaine in Tijuana.

Magda Stuglik

Ibogaine’s Origins as Therapy

If you’ve never heard of ibogaine, you’re not alone.

When taken correctly, the treatment is prohibitively expensive, serving the few with several spare Gs. Averaging about $1,000 a day, a low-cost program runs around $6,000 in total, but the pinnacle of luxury treatment centers visited by A-listers can cost six figures for a cushy month-long stay. The root is available on the black market for $35, but self-administration is not recommended and is reportedly responsible for most of the fatalities associated with ibogaine.

“[Self-administering] is the dumbest thing you could ever possibly fucking do on this planet,” said Dr. Charlie Powell, a four-time board-certified physician from North Texas and military veteran who went to igbogaine therapy in Mexico in 2023 to treat PTSD and opioid dependence. “Because now you’re not getting the protection of the medical side of things to protect your heart and your safety. You’ve got to have the pre-work, the post-work. … This is not an antibiotic. You’ve got to do the program.”

Inaccessibility and the taboo nature of rehabilitation centers keep ibogaine a hidden gem among hallucinogen enthusiasts. Powell, who worked in the medical industry for 26 years before selling his facilities for $250 million, was recommended ibogaine for PTSD during a lengthy tattoo session. He had never heard of it before.

“When [my artist] said the words one day, ‘psychedelic medicine,’ those two words don’t belong in the same book,” Powell said. “I had all the technology, I had imaging centers, I had just about every bit of high-tech thing you could have in medicine. I didn’t know about this. [I thought] it must not be any good because if it were any good, I would know about it.”

But Powell’s PTSD was unrelenting, and as he watched more of his former platoon members die by suicide, he worried his obit would be next if he didn’t try something new, even if it were experimental.

The drug made its way to the main stage in Texas through the Texas Ibogaine Initiative, an advocacy organization spearheading the research endeavor. The initiative has won support from a slew of big names, including U.S. Rep. Morgan Luttrell, who is open about his experiences using ibogaine, and U.S. Rep. Dan Crenshaw. Both are veterans. However, the top-bill names belong to former Gov. Rick Perry and right-leaning podcaster Joe Rogan, who joined forces for an episode on The Joe Rogan Experience podcast to discuss ibogaine.

Perry has been clear about his belief that ibogaine is the way of the future.

“I don’t care if you’re a Republican or a Democrat,” Perry wrote about ibogaine in an op-ed for the Washington Post. “Every one of us knows someone who’s struggling, whether with addiction, trauma or mental health. This is the cause I will dedicate the rest of my life to fighting for, because too many lives hang in the balance to do anything less.”

The discovery of ibogaine as a therapeutic remedy was by chance. In the ’60s, a 19-year-old heroin addict from the Bronx named Howard Lostof, desperate for a new type of high, tried iboga root that he procured from a local chemist. After 30 introspective hours spent tripping, Lostof came back to cognisance without craving heroin.

By happenstance, the former addict was thrust into a lifelong career in pharmacology after accidentally discovering the addiction-combating properties of iboga. He administered the treatment to his similarly addicted peers with the same results, proving his hypothesis and, to a degree, changing opioid rehabilitation forever. He spent the remainder of his life championing the medical benefits of the root, and in the ’80s, he patented a capsulized version, ibogaine, produced exclusively for rapid opioid detox. Ibogaine was scheduled before he was ever able to begin his research.

Almost 50 years later, some ibogaine experts worry that Texas may not be the best launchpad to pick up where Lostof left off. While most would like to ensure that veterans are well cared for, we may have to reconfigure our healthcare system, or the benefits of the risky drug are moot.

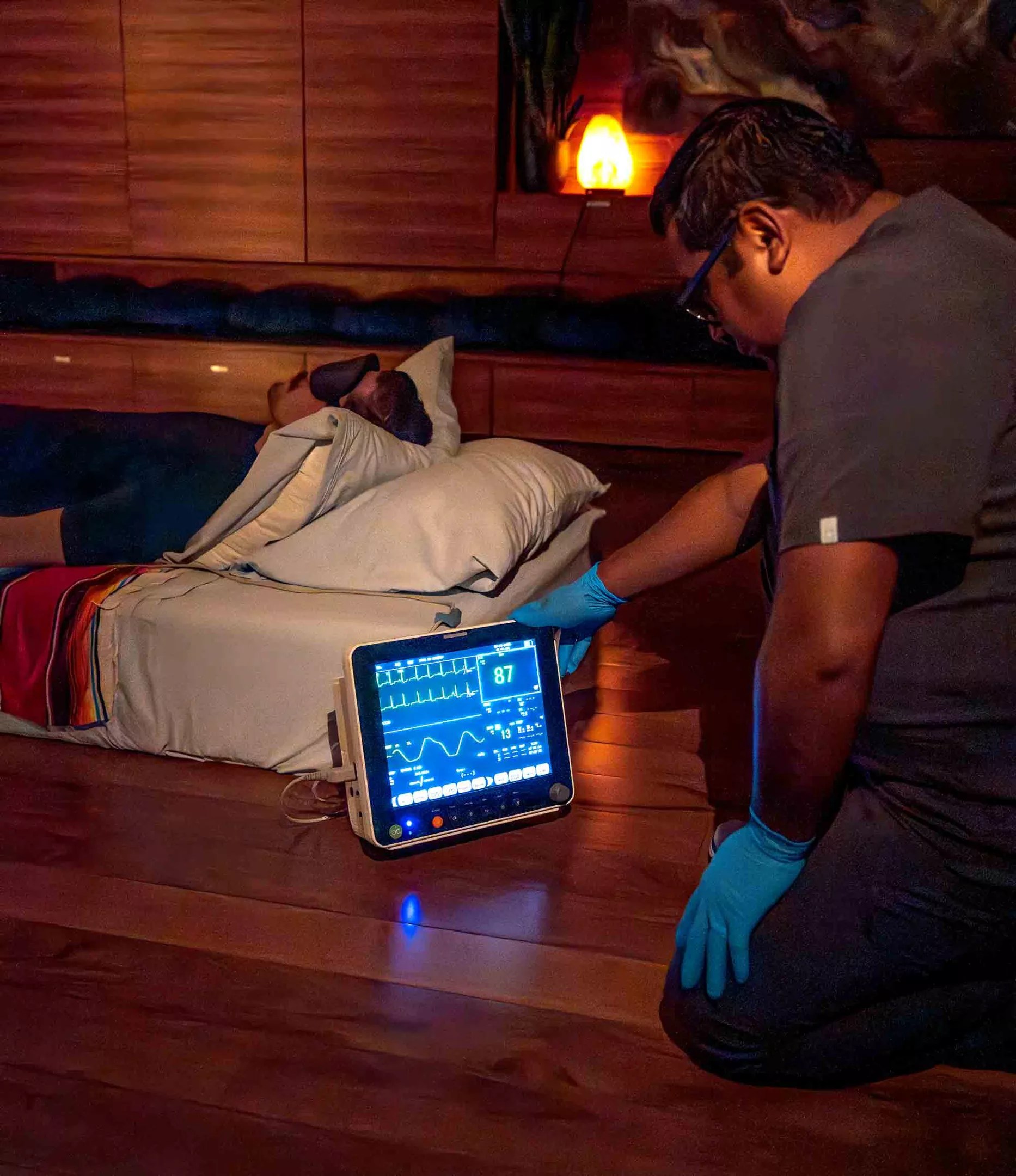

During the Ibogaine treatment, the patient’s heart rate is monitored for safety.

Magda Stuglik

Around The World in an Eight-Hour Trip

Ibogaine is not an entry-level experience, and it’s not for the faint of heart. Literally. This isn’t a face-melting acid trip that turns the world into a kaleidoscopic picture show and gives voice and visage to the inanimate.

To the onlooker, an ibogaine trip is boring. There are no convulsions, no silly streams of consciousness, no proclivity to leap off the side of a building in hopes of sprouting wings and catching air, and, if all goes according to plan, no heart arrhythmias. While no trip is the same, it’s uniformly introspective and described as living a thousand grueling lifetimes with infinite experiences and sensations in just a few hours.

“I must have lived at least a hundred events in my life over again in third-person,” Powell said. “Everything fit into place, things I didn’t consider, traumas that really messed me up and I didn’t realize it. I was able to real-time integrate and understand. I came out of that not just happy. I came to peace.”

Some envision a spirit guide who takes them through their every memory, a hand-held stroll through their unprocessed trauma, like Dickens’ Ghost of Christmas Past. Others see visions similar to memories but not quite the same, carrying the familiar and uncomfortable deja vu of a recurring dream.

“Pardon my language, I was tripping balls,” Powell said. “Some people have a guide, some people don’t. Mine showed me a lot of things. It was more than I can even begin to understand.”

Three-quarters of patients experience vomiting, a common side effect of ibogaine, and in Bwiti, it’s interpreted as the expulsion of the past. But for the most part, ibogaine induces a state called ataxia, or the extreme loss of muscle coordination to the point of immobility, confining most people to a bed.

Becoming a stationary blob and occasionally retching sounds easy enough to manage in an American clinical setting, but the emotional toll of an ibogaine high necessitates extensive preparation beyond standard Western medicine, according to Trevor Millar, co-founder of Ambio Life Sciences, a leading ibogaine rehabilitation facility in Tijuana. Millar’s colleague and business partner, Jonathan Dickinson, is the lead author of Clinical Guidelines for Ibogaine-Assisted Detoxification, produced by the Global Ibogaine Therapy Alliance, which sets international treatment standards for the therapy.

Ambio is soon expanding to Malta, where it will use the therapeutic techniques and standards drafted by Dickinson. Very few countries have laws for or against ibogaine, leaving it in a legal gray area in most places. It’s not technically illegal in Mexico, but it’s also not legalized by formal law, allowing Ambio and other resorts to distribute the medicine without penalty.

“We are fully licensed as a mental health and addiction clinic in Mexico, but there is no specific licensing around ibogaine itself,” Millar said. “It is not on any books. The interesting thing is, there are UN treaties that most countries in the world have agreed to, and those UN treaties make most drugs illegal, even if the country wanted to make them legal. Ibogaine isn’t on any of those UN treaties. That’s the gift so far.”

Ambio operates on an application-only basis. Because of the serious cardiac concerns, a complete medical screening, including a list of every substance the patient has ever consumed, an EKG and a complete blood panel, is required before you book your stay. Ambio requires a minimum of two pre- and post-treatment counseling sessions, which Millar said should be the industry standard. Done the right way, he said, the experience is truly life-changing and a gift to be a witness to.

“To see somebody detox off opiates, I’ve seen thousands of treatments now, it doesn’t get old,” Millar said. “It’s still remarkable to see somebody pop out the other end of a treatment like that.”

To get to Ambio, you fly into San Diego and are chauffeured 30 minutes across the border. At the clinic site, patients will meet their trip companions in a group therapy setting. Millar says they are often bonded for life by the end of the week, especially in the program that predominantly serves veterans. Before ibogaine distribution, patients undergo a series of treatments blending facets of traditional Mexican medicine, like sweat lodges, and sacred Bwiti practices, like several-course feasts. Patients in the addiction detoxification program typically require a longer stay to certify a few days’ worth of sobriety before the trip. Several times before capsule distribution and the impending yack, hydration gets boosted through intravenous magnesium and saline supplementation, and heart rates are regularly monitored.

Millar says any cardiac issues that could arise are relatively easy to screen out before treatment, and notes that he’s never had a fatality at his treatment center. Just in case, a cardiologist is on call.

In the final hours before treatment, patients gather around a bonfire to bid adieu to their past worries before taking the first capsule in unison. They are soon guided to the treatment room, attached to an EKG machine, given the remainder of the capsules, and lie down to ride it out and awaken anew. The crash from the powerful high of ibogaine packs just as strong a punch. Patients are prepared for their seismic rebound to Earth’s surface, which takes an entire day to recover from, called “gray day”.

Many of the licensed ibogaine facilities in Mexico fuse Eastern and Western medicine, which ibogaine industry experts say is crucial, and that will need to happen before Texas can emerge as a reputable destination for ibogaine therapy in the distant future.

“As things unfold in Texas, there’s a very good chance that for quite some time, what’s happening in Mexico is going to be better than what happens in Texas,” Millar said. “My encouragement, again, to Texas, is let’s start with the end in mind. … It’s going to require some tweaks to the medical system as we know it. It needs to be comfortable and loving and very supportive. And yes, still medicalized, but let’s skip this sterility of a hospital, perhaps.”

Texas Tries To Ban Getting High, But Not All Highs

The ibogaine bill, Senate Bill 2308, filed by North Texas Sen. Tan Parker and signed into law by Gov. Greg Abbott, creates a consortium to “conduct United States Food and Drug Administration’s drug development clinical trials with ibogaine to secure the administration’s approval of the medication’s use for treatment of opioid use disorder, co-occurring substance use disorder, and any other neurological or mental health conditions for which ibogaine demonstrates efficacy and to the administration of that treatment.”

The collection of businesses and entities comprises higher education institutions, hospitals, the state Health and Human Services Commission, the comptroller and a drug developer. The bill almost passed unanimously, with Texas Republicans and Democrats uniting in rare bipartisanship. Only four of 138 voting House members voted against the bill; one of them was a Democrat. Similarly, four of 31 voting Senators voted against the bill, all Republican.

“I support ibogaine research, but I do not support government picking winners and losers or raising taxes to do it, which is exactly what the Legislature did,” Rep. Brian Harrison, one of the only nay voters, wrote to the Observer in an email. “Also, the hypocrisy is stunning: The same Legislature that banned hemp products is forcing taxpayers to fund psychedelics.”

Harrison was the only Republican to vote in opposition to the THC ban bill and was the only Republican who urged Abbott to veto the legislation. Abbott did.

But Harrison is the outlier of the Texas Republican Party’s current approach to drugs. A majority of his colleagues voted oppositely, approving an outright ban on THC while also making exceptions for ibogaine research. One of those lawmakers is ultra-conservative Rep. Mitch Little, a proud lifelong Republican from Denton County.

“From what I understand, knowing very little about [ibogaine] from a scientific standpoint, this has been groundbreaking for [veterans] lives so that they could kind of gain some freedom,” he said to the Observer. “Because [it is] still a Schedule 1 drug in the United States, there’s very little likelihood of abuse because of the medical controls on it. Allowing the state to engage in trials for something that could give people some mental and physical freedom, I think, is a good thing to do.”

Ahead of the THC ban, which lawmakers are still negotiating in the ongoing special session, there was an outpouring from veterans who use legal THC products as an alternative to addictive opioids, begging lawmakers to allow them to keep their products. Veterans were a named party of concern in the governor’s veto.

“I understand that some veterans report improved daily lives or outcomes as a result of THC,” Little said. “There may be causation there. There may just merely be correlation.”

Little also notes that a THC ban is connected to the state’s supposed inability to regulate THC products the way it does alcohol, and not merely because it’s an intoxicating product. In his view, there’s little comparison between the THC argument and this new, tightly controlled ibogaine issue.

To be clear, the bill does not give a green light for ibogaine research, and Perry told the Texas Tribune that we are still likely many years out from actual human testing. However, the Health and Human Services Department is required to accept grant applications until Aug. 20, 2025. The bill’s passage alone, with a heap of Texas tax money, is a landmark for the future of ibogaine and hallucinogen research in the United States.

“To better understand the potential for ibogaine and to better address the public health challenges caused by things like opioid use disorder, an FDA clinical drug trial is needed,” Abbott said at the bill signing ceremony. “Many of these veterans suffer from so many different types of injuries, both seen and unseen. … The same is true for some of our first responders, as well as others who are dealing with addiction-based issues.”

While the price of a luxury Cozumel ibogaine retreat surely elicits a bit of sticker shock, the American health industry is not known for its affordability. The cost of care in our neighboring nation is much lower than our own, and if, or when, ibogaine is launched as an FDA-approved treatment in the U.S., likely without immediate insurance coverage, Ambio’s Millar said, those with their fingers deep in the industry could see a sizable payout. Texas knows that.

Under SB 2308, the state will receive a minimum 20% stake in the profits of a successful pharmaceutical produced in state-funded trials. A portion of that cut will be carved out for veteran services.

Millar also points out that American pharmaceutical companies, which are some of the largest political donors, make unimaginable profits off the opioids frequently prescribed to veterans. They also cash quite a few zeros from opioid addicts prescribed Suboxone, a branded combination of buprenorphine and naloxone, an opioid addiction treatment that has to be taken daily in perpetuity. Big Pharma is not set to benefit financially from standardizing a one-time treatment with a high efficacy rate.

“Ultimately, I would love to [see] clinical trials,” Millar said. “I think if insurance companies are actually looking to help people heal, this is a more cost-effective way. Sadly, I’m not convinced insurance companies are committed to seeing people heal. I call it the ‘opioid racket’, [a move] to keep somebody on Suboxone or methadone for life.”

Ibogaine is taken in pill form.

Magda Stuglik

Ibogaine Is not the Cure They Think It Is

Unlike most illegal substances, there are few oppositional voices against ibogaine as a substance or even as a therapy. Ibogaine, on its own, is not highly addictive and is relatively hard to obtain, unlike the drugs of primary concern in the United States, like fentanyl. If you did get your hands on it, the chances that someone would take it recreationally, understanding the heart risks, are minimal. Most dissenters cite fiscal or systemic concerns, but there is a small sector of ibogaine experts who disagree with the narrative being spun by the GOP that presents ibogaine as a one-stop cure.

“[Republicans] have systematically destroyed the community of care and presented this drug falsely as a miracle cure,” said Dimitri Mugianis an avid harm reduction advocate and one of the only Americans ever charged with felony possession of ibogaine. “Part of their argument is [it’s] a cure to social disruption. We’ll do away with homelessness by giving people ibogaine, or we can cure PTSD for folks that we’ve sent away to kill and die, when they’re experiencing the very human emotions that we hope would accompany such activities.”

Mugianis is pro-research. He thinks we should know more about the drug and all of its benefits, but he disagrees with the packaging and the pretty red bow Texas lawmakers have tied on top, which he says distracts from other pitfalls.

“They’re talking about a miracle cure when what it really is is an opportunity to care for folks,” he said. “And caring for folks costs money, and it takes skilled people. They’ve done everything they could to destroy that safety net, to destroy people’s access to skilled people and people’s [access to] getting the education to become skilled.”

The dichotomy between approval for ibogaine trials and the crackdown on THC has garnered a bit of scrutiny, but Mugianis is clear in his opinions.

“I don’t know how this move is a ‘changing attitude’ towards drugs,” he said. “It doesn’t register as that. As a matter of fact, it seems like it’s the same attitude towards drugs. … I do object. It’s not just the commercialization that I object to, it’s the overmedicalization,” he said.

He also does not ignore the appealing economic future of ibogaine research for Texas, crediting it as a potential reason for the shift in pitch.

“I’m looking at these people who have not given a shit about poor and working people, who have not given a shit about drug users, who’ve not given a shit about veterans,” he said. “Suddenly, they’re all compassionate. I don’t believe it.”

There are also concerns about the production of ibogaine and stripping the supply from the people of Gabon as demand grows internationally. The iboga root takes five to seven years to mature for harvesting, and Ambio is working on ethical sourcing practices that allow people to reap the benefits of the root at a large scale while preserving the sanctity of the Bwiti.

“People operate as if there’s no template, as if there’s not a history in which we can look at and say, what would happen when we take a good practice, for instance, and put it within the institutions?” Mugianis said. “Suddenly, therapy becomes this one-size-fits-all box. What happens when countries with money come and take from countries with resources? Some people are trying to counter that. But I don’t think those Republicans have thought much about biopiracy.”

He also points out that because clinical research is so limited, ibogaine’s purported efficacy is questionable and requires much more nuanced definitions as opposed to a blanket application to all drug problems.

“The problem is the story they’re telling, the story that it has an 80% success rate,” he said. “These drugs do not deal with fentanyl very well.”

Mugianis and Millar also expressed similar worries about government involvement in clinical research when it pertains to opioid addiction, cautioning against the theoretical forced ingestion of ibogaine to eradicate substance abuse. (We could not find any such proposal by any Texas lawmakers.)

“There’s a way to do all this right, but not within this structure,” Mugianis said. “But when it comes to money, they don’t give a shit. That’s what I think.”

Texas Has Time To Shape Up

While Texas is the first state to successfully pass any legislation that comes close to getting ibogaine into the U.S. in a legal way, we’re still years from the execution of clinical trials.

Experts in the ibogaine industry certainly don’t view the United States or its respective pharmaceutical and wellness companies as potential competitors in the market. But if the day comes, they’d at least like to see Texas facilities embrace holistic and spiritual wellness for the betterment of people without financial gain as the driving force.

The good news is that Texas has plenty of time to catch up and construct some sweat lodges and install more EKGs because, without approval from the Federal Drug Administration, which could take years to achieve, ibogaine remains a banned substance without exception.

“[Ibogaine as a cure to the opioid crisis and PTSD] is unachievable because they’ve destroyed the infrastructure and continue to destroy the infrastructure which is necessary for these things to work,” Mugianis said. “I’m not pro-ibogaine. I’m pro-people being kind to each other, and heal. If ibogaine is part of that, that’s fine.”