Delcia Lopez

Audio By Carbonatix

Shortly after entering a tiny closet-turned-viewing room, Trinidad Gonzales saw something he still struggles to describe 20 years later. The doctoral candidate had a couple hours of microfilm to review, and toward the end his eyes ached so much that he almost missed it. Almost.

He scrolled past the paragraph, then quickly did a double-take. Yes, there it was: his family’s name, in the middle of a 1929 editorial from the Edinburg newspaper El Defensor. The column castigated a local sheriff for his involvement in the decade-long scourge of murders known as La Matanza (The Massacre), a period of deadly violence against Mexicans and Mexican-Americans in Texas that began in 1910. This was of particular interest for Gonzales, a history student at the University of Houston. He had grown up hearing stories about his ancestors’ deaths and the state-sanctioned murder of Mexicans, but this was the first time he saw his family’s name mentioned in print as victims.

“When you see something that correlates with the story you’ve been told, it’s an interesting feeling,” he says. “I don’t like the word ‘affirmation,’ because that feels like I’m not giving enough weight to my family’s word. But I don’t know how to describe it.”

Gonzales, now a professor at South Texas College in McAllen, is part of a group of unknown size: descendants of victims of the Texas Rangers. He is also a co-founder of Refusing to Forget, a nonprofit dedicated to sharing the history and enduring effect of the Rangers’ violence. Thanks in part to the organization’s efforts, there is now greater knowledge than ever before of the Texas Rangers’ brutal past. The question is, what to do with this knowledge?

The exhibit, Life and Death on the Border: 1910–1920, is on display at South Texas College.

Delcia Lopez

Some people, like Gonzales, want a formal, Texas-led investigation in the form of a truth and reconciliation commission. Others aren’t sure what they want, but they know they want something. An acknowledgment and formal apology, perhaps. And both camps agree there are disturbing similarities between the Rangers’ violence and the killing of Black men like Tyre Nichols, as well as the racially charged rhetoric that often dominates the discussion of the Texas-Mexico border.

“When you dehumanize a whole group of people, it is easier to mistreat those people, and that is the danger we still see from the past to today,” Gonzales says.

In an interview with NPR about his book Cult of Glory, Doug Swanson said of the Rangers: “You know, they didn’t invent police brutality, but they perfected it down there on the border, where they operated as what we would now term death squads.”

Founded in 1823 by empresario Stephen F. Austin, the original Texas Rangers were a private force tasked with protecting Austin’s colony of Anglo settlers from attacks by Native Americans whose lands were being settled. The Rangers became an arm of the Texas government in 1836, serving as Indian fighters, hunting bandits and patrolling the Texas frontier in the 19th century. Rangers also fought as scouts for the U.S. Army in the Mexican-American War and earned a reputation for lawlessness and brutality.

Today, the Rangers’ 166 commissioned officers are part of a division within the Department of Public Safety, investigating major violent crimes, public corruption and officer-involved shootings.

Mythologized as symbols of law and order on the Old West frontier, yesterday’s Texas Rangers were also the perpetrators of large-scale atrocities and an unknowable number of murders. At least 300 Mexican Americans were killed in Texas in the 1910s, for instance, and some estimates place the number in the thousands. The Rangers were often the ones pulling the triggers or raising the nooses, and their acts made them as feared as the Ku Klux Klan. Worse yet, they did it all with relative impunity.

This legacy is now part of a traveling exhibit from Refusing to Forget. Originally shown in 2016 and now returning for an encore that began at South Texas College on Feb. 9, Life and Death on the Border: 1910-1920 is a collection of photographs, court records, correspondence and artifacts telling the story of life at the height of the Rangers’ murderous reign. In that sense, the exhibit offers powerful counter-programming to the Ranger museum in Waco and the century of films, television shows and dime novels lionizing the lawmen. But ultimately the exhibit is not about the Rangers.

Ben Johnson, a history professor at Loyola University Chicago, is another co-founder of Refusing to Forget.

Delcia Lopez

“The exhibit certainly touches on the Rangers and what is probably their most controversial set of events, but it’s not focused on the Rangers themselves,” says Ben Johnson, a history professor at Loyola University Chicago and another co-founder of Refusing to Forget. “It’s the story of the South Texas communities in the nineteen-teens and their impact. We’re claiming this place for ourselves and relaying its history, some of which is bad. It’s a labor of love.

“In a tug of war about policing or the Rangers, we lose sight of the victims and their families,” he adds. “That’s one of the reasons it’s called Life and Death on the Border, to be blunt. There are family photos, including people who ended up being killed. We don’t want them to be victims whose only significance is that they got killed.”

Knowing the people beyond the tragedy is a motivator for Gonzales too.

Before he was a historian, Gonzales was a reporter for the McAllen Monitor. While investigating a major story, he had an innocuous run-in with a modern-day Ranger, who called and asked if Gonzales could share his source. As it turns out, the Ranger was investigating the same crime.

He eventually ditched journalism for history and found plenty of overlap with his former career. Gonzales was still investigating, only now the crimes happened a century or two ago.

That’s how he found himself in that cramped document viewing room, straining his eyes to complete his dissertation. After he saw his family’s name, he called his mother, who he says was surprised at the find. Then they talked – for six hours – about their family and the stories they were raised on. Some of the stories were violent, but many were not.

“My great grandmother died when I was about 5,” Gonzales recalls. “She owned cattle, and she owned a grocery store.”

Later, he is thinking about his mother and great grandmother while weighing the question so often asked of historians like him: “Why do you want to focus on the bad things the Rangers did?”

“People will say things like, ‘You’re just opening old wounds,'” he says. “But the wounds never healed.”

They Were All Good Mexicans

The area where the Porvenir Massacre occurred was as harsh as its history. “Each plant in this land is a porcupine,” wrote one 19th-century traveler quoted in Swanson’s book. “It is nature armed to the teeth.” Texas Rangers Company B undoubtedly passed some of those “porcupines” as they rode into the village of Porvenir, on the Texas-Mexico border west of Marfa, on Jan. 26, 1918. Their mission was ostensibly to find a Mexican revolutionary named Chico Cano, but an Army cavalryman named Robert Keil doubted Cano was in Porvenir.

“They were all good Mexicans,” he said of the villagers. “These people were our friends.”

After a search of the huts yielded a shotgun and some knives, the Rangers escorted a group of 15 men and boys to a nearby bluff. They killed the villagers and later burned the huts. A 12-year-old boy named Juan Flores watched his father being led away, then saw his body. Yet he didn’t share his story until he was 95.

Christine Molis learned about her ancestors’ murder as an adult. Now she wants to learn as much as possible about La Matanza.

Delcia Lopez

“My father never wanted to talk about his family when I was growing up,” Flores’ daughter Benita told TIME magazine. Then one day Benita came across a list of Porvenir victims, and a name sounded familiar: a man named Longino, who had three kids. One was a boy named Juan. “I went and I asked my father, ‘Are you this 12-year-old boy?’ And he said yes. It was very hard for him to tell us what happened that day, but slowly he started telling us.”

The massacre is now the subject of a PBS documentary and its own website, which is edited by Arlinda Valencia, Longino’s great-granddaughter. Valencia was at a family funeral when an uncle mentioned the massacre, and at first, people laughed. It sounded too crazy to be true. But Valencia did some digging, and there it was. She has since spent untold hours visiting libraries and searching for documents, all the while amassing an impressive repository of details on the web. And like Gonzales and the members of Refusing to Forget, she is intent on sharing history that still feels tethered to our current moment.

“What happened 100 years ago is happening again today,” Valencia told NBC News after the 2019 mass shooting at an El Paso Walmart. “In El Paso, 22 people were murdered because of the color of their skin. In Porvenir, it was 15 people. It’s just something that shouldn’t be happening.”

Christine Molis has a story similar to Valencia’s in that she didn’t hear about her ancestors’ murder until she was an adult. Neither did Molis’ mother. (“It was ‘adult talk,’ my mom said,” Molis tells the Observer.)

Molis is the great-great-granddaughter of Jesus Bazán. On Sept. 27, 1915, Bazán and his son-in-law Antonio Longoria were shot and killed because, according to The Guardian, Rangers thought they were cattle rustlers.

“You hear so many racial stories throughout history, but it kind of hits harder when you find out it’s your history,” Molis says.

She is drawn to the work being done by Refusing to Forget, and she was in attendance at the opening of the new Life and Death exhibit. The knowledge of her great-great-grandfather’s death has helped her find a new community.

She first heard about the organization when it was opening the original exhibit back in 2016. Her mother was invited to be a part of a panel, and since then, Refusing to Forget has periodically reached out asking for details or other family stories.

“From what I understood, and what I gathered from the stories I would hear, it was a struggle for these single moms to raise their kids alone,” Molis says of her family’s life after the murders of Bazán and Longoria. “There were hardships, and the family had to pull together and help each other move forward and find ways to survive without the men. The children would have to go to work very young and help make sure the family has food. A lot of them did farm work.”

Hearing that, she says, made her want to learn “as much as possible” about the other families.

“Now it’s, ‘What else can I learn about what happened? How much more is there?'”

Like many descendants, Molis finds herself wondering what’s next. She has the knowledge; she has new connections. What should justice look like for all these families like hers?

“I’m trying to find the right word,” she says. After a pause, she continues.

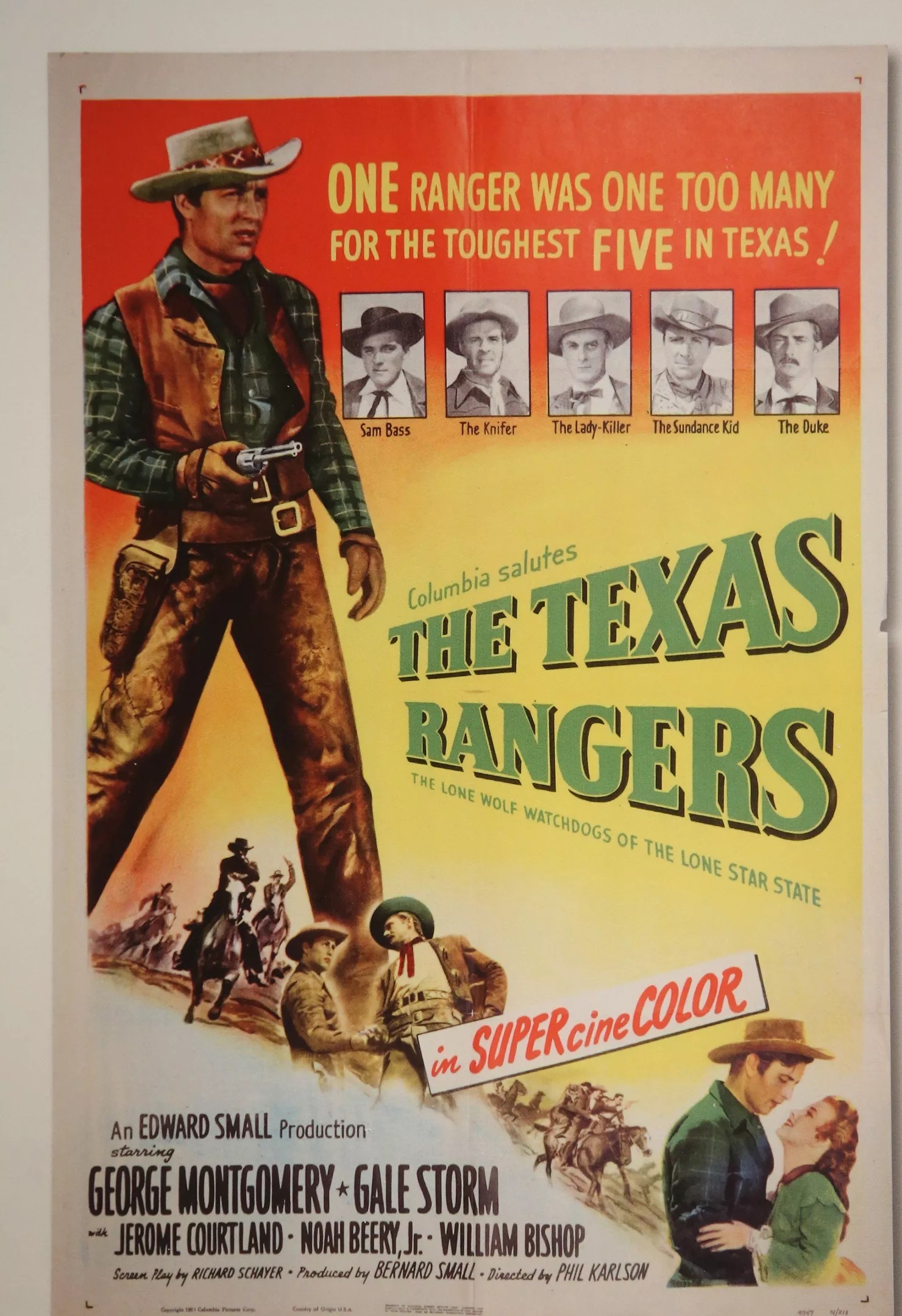

Texas Rangers were depicted in pop culture as heroes.

Delcia Lopez

“I want it to be acknowledged. I would like for it to be acknowledged that this is history, this did happen. Because there are families out there that are hearing these stories and know it happened, but they’re still pushing it under the rug. I’m not looking for apologies, just affirmation that, ‘OK, this did happen.’ Something to the effect of, ‘Hey, we’re looking into this. We can’t correct what happened, we can’t go back, but moving forward, we can do our homework.'”

The Observer reached out to the Ranger museum in Waco to ask if it would consider incorporating some aspects of the force’s violent past into their existing exhibits, but the museum did not reply. We also contacted the governor’s office to inquire about the possibility of a truth and reconciliation commission, but the governor’s office did not respond.

As Gonzales describes it, a truth and reconciliation commission could be led by one Democrat and one Republican. The two parties would investigate the history of state-sanctioned violence in Texas, then make recommendations for how to “rectify those wrongs.”

“I know I want an apology, but I don’t have all the answers yet,” Gonzales says.

Many people have advocated for the Texas Rangers baseball club to change their mascot, as San Antonio College recently did after a student-led campaign. Yet the baseball club has indicated it has no plans to change its name.

“The name change isn’t gonna happen anytime soon,” says Christopher Carmona, an author whose descendants fled to Mexico to escape Ranger violence. “We barely got the Redskins to change their name,” he notes, “and that was a 30-year campaign.”

When the topic of justice comes up, Carmona says it’s ultimately about doing whatever is going to bring descendants peace. That means something different for each community.

He cites the example in San Diego, Texas, in Duval County. Three San Diego men were murdered by Rangers in 1920, and recently the town invited Carmona to speak at an official county proclamation acknowledging the killings. More than a century after the deaths of their grandfathers, three women in their late 80s finally heard local officials say, “This happened.”

“That was a huge step for the family,” Carmona says. “They were satisfied they got that documentation.”

Carmona is working on the next installment of his young adult series El Rinche, a collection of novels set during the time of La Matanza. It’s always a delicate balance to take these stories to a younger audience, he says, but it must be done. Plus, his books include a Latino superhero: a rare sight for his readers. When it comes to depicting violence like, say, a lynching, Carmona says he leans into his background as a poet, describing the effect of the violence on the people exposed to it without delving too deeply into gory descriptions.

Life and Death on the Border: 1910–1920 is a collection of photographs, court records, correspondence and artifacts telling the story of life at the height of the Rangers’ murderous reign.

Delcia Lopez

“The most challenging part of writing this is being respectful to the victims of these lynchings and murders,” he says. “As a writer, we need to present what happened. At the same time, we need to respect the dead. So that is the biggest challenge for me: balancing the respect for real-life victims and telling the stories.”

His books incorporate real-life characters, too, including the poet and folk hero Aniceto Pizaña, who pops up in the second El Rinche adventure. After delivering a presentation in Brownsville about the first book, a boy approached Carmona to ask if he knew Pizaña. The boy didn’t know the revolutionary would soon appear in the second El Rinche novel, but he had a special connection to Pizaña.

“He was my great-great-grandfather,” he told Carmona.

Years later, Carmona still marvels at the conversation.

“Our people are still here,” he says, “and these stories are a part of us.”