Joe Griffin

Audio By Carbonatix

A funny thing happened to spaceflight in the late 20th century: Engineers began to design new launch vehicles that could reach space but operate like airplanes. Instead of a rocket standing upright on a launchpad, blasting into space under tens of thousands of pounds of mixed fuel and oxidizer, aerospace companies began to design aircraft that could use runways to enable payloads to reach space.

These come in basic varieties: Airplanes that can launch space rockets from altitude, aircraft with rocket engines that can shoot into space and land on their own, and spaceplanes that would launch on the tips of rockets, operate in space and need a place to land. These launch concepts have attracted the attention of airports across the country.

This increase in interest has been lucrative for Brian Gulliver, who leads the aerospace and spaceport practice at the firm Kimley-Horn. Gulliver is a professional engineer with experience designing launchpad equipment for NASA and Air Force spaceports. These days he’s one of a handful of consultants with any experience who can help transform airports into spaceports, as designated by the Federal Aviation Administration.

His latest client: The Greater Waco Chamber of Commerce and Texas State Technical College (TSTC), which hired the consultant for nearly $200,000 to analyze the possibility of creating a spaceport at the school’s airport. In late December, a draft of the study found the airport’s infrastructure could handle the operation of airplanes that launch space rockets or some spaceplanes that can use their own onboard engines to blast into space. The runway could also handle spaceplanes that launched elsewhere and need a place to land.

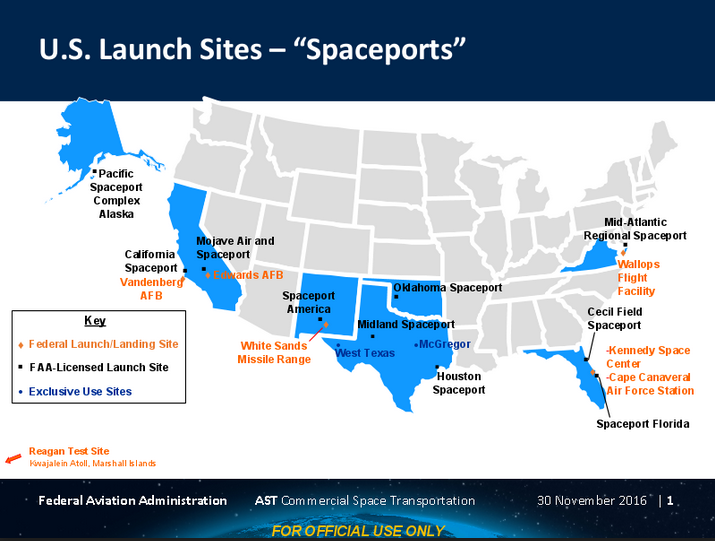

This map shows Texas has the most FAA- designated spaceports in the nation.

FAA

The designation of Waco’s technical college as a spaceport would be the latest in a string of high-profile efforts to make Texas the epicenter of the commercial space industry. Texas already leads the nation in places designated by the FAA for commercial space launches: SpaceX’s under-construction launchpad near Brownsville; Midland-Odessa’s airport, designated in 2015; and Houston’s recently announced conversion of Ellington Field to a spaceport. Other space launch work – FAA exclusive use permits for commercial space launches – is done in West Texas, where Jeff Bezos’ company Blue Origin is developing and flight-testing reusable rockets; and SpaceX’s engine test facility in McGregor, outside of Waco, where the company tests its Dragonfly vehicle to practice rocket-powered landings.

The private space boom has been driven by ambitious billionaires, an attitude change within NASA and demand from satellite launchers looking for affordable alternatives. But at the turn of the century, the commercial space world remained fixated on the familiar style of launches. Until aerospace firms started creating new spaceplanes, everything Gulliver designed for new spaceports supported rockets rising from launch pads. “The idea was a bunch of smaller, vertical lift pads, like mini Kennedy Space Centers,” Gulliver says.

But that was soon to change as more companies joined Virgin Galactic in commercializing spaceplanes and a new generation of air-launched rockets. In 2010, Florida made a move that opened the eyes of many smaller airports with big ambitions.

Officials with Space Florida, the state’s official economic development agency, knew that spaceplane programs at the Kennedy Space Center would need a home after they left the cradle of NASA development. The state agency wanted to make sure that there were runways available in case these projects ever got off the ground. So Cecil Field, near Jacksonville, solicited the FAA and received its designation as a spaceport. There, the airplanes would fly over the open ocean, drop the space rocket and veer away as its engines ignited.

Gulliver worked on the certification in Florida and saw it could be repeated. “After the Jacksonville project was done, we saw there was a market emerging to help spaceports co-locate at existing airports,” he says.

He went on the road, pitching the idea to airports by presenting papers at space conferences. “While commercial spaceports that support vertical launches are still being developed, the largest growth has been in spaceports designed to support the horizontal launch sector,” reads one, presented in 2012 at the AIAA Space Conference in Pasadena. “In addition these, new commercial spaceports are being developed in more diverse locations around the country and will soon be more numerous than traditional spaceports.”

Just like the early ’60s, Texas is vying with Florida to be the center of spaceflight, but this time with the hope that commercial entities will operate the spacecraft and paying customers will replace government astronauts. It’s an ambitious dream, and Waco is now part of that effort, reaching for orbit and using every trick in the economic development book to get there.

Best known for its plans to put tourists into sub-orbital spaceplanes, Virgin Galactic also wants to launch satellites from airplanes. Work on this project is being done in Waco – a sign of things to come?

Virgin Galactic

In the first week of January, the week before classes begin at Texas State Technical College in Waco, the campus is post-holiday sluggish but shows signs of renewed life. The bookstore is open, but the staff outnumbers the shoppers. Signs warning of late registration fees are posted around the student center, but almost none of the nearly 6,000 undergrads who attend are around yet to read them.

TSTC focuses on two-year training in practical, professional trades. The dozens of disciplines taught here read like a register of steady-demand skilled labor: electrical line workers, refrigerator techs, dental assistants, land surveyors, landscapers and computer system engineers.

The disciplines are pretty bread and butter, but TSTC has something no other college can match: the largest airport owned by an educational institution in the United States. TSTC airport dominates the eastern fringe of the campus, complete with two runways and an air traffic control tower. It’s a general use airport, and anybody flying by can radio the tower and land there. A subset of students here aims at niche aviation work, like avionics repair, aircraft maintenance and air traffic control. There are also industrial tenants at TSTC and mammoth hangars, some with doors towering more than 65 feet high, indicate the size of the airplanes that come here for maintenance work.

An Air Force training flight takes off from TSTC airport, with defense contractor L-3 Technology’s hangar in the background.

Joe Griffin

Today, three white jet planes are wheeling over the airfield in wide oval, racetrack patterns. They land and takeoff again without fully stopping, what pilots call a touch and go. Inside the cockpit are Air Force trainees getting practice time in twin engine T-1 Jayhawks. These are the planes that airmen fly to learn how to operate larger cargo haulers and aerial refueling tankers, and TSTC is a favored place to practice approaches and stop for lunch.

The airfield sees an impressive annual 101,000 takeoffs and landings and hosts a major airshow every year. Air Force One landed here when George W. Bush was president, ferrying him to his Crawford ranch. Not bad for an airport that doesn’t even have its own radar.

Kevin Dorton, the airport’s manager, watches the T-1s from the catwalk atop the ATC tower. Then he points in the other direction, to a hangar and several gray, 167-foot-long airplanes. One of the airplane’s propellers is spinning. “I think those are P-3s with the Royal Australian Air Force,” he says, not entirely certain of the identification.

He’s more certain when it comes to the funding history of the hangars the P-3s are using. In 2014 the airport determined that the World War II-era building needed $4.4 million in modernization in order for P-3 military aircraft to have work done here. When airports stare at such bills, they turn to myriad places to help defray the cost. Targeting and collecting public state and federal cash is a basic part of running an airport.

Dorton would have gone to the Texas Department of Transportation for grant money, but those funds are reserved for routine repairs and improvements. The school turned to local government, and the city and county provided $1.1 million under the banner of economic development. The company that rents the facility, L-3 Technologies, chipped in $900,000. TSTC got a $1.8 million low-interest loan from the governor’s office and paid $600,000 out of pocket.

Airports are often staffed with aviation fanatics who have one eye fixed on the airspace above and another begrudgingly focused on spreadsheets on the ground. Dorton, a former bank auditor and moonlighting rancher, is not one of these. Ask him if he wants to learn to fly and he plants his legs a little wider and says, “I want to stay firmly on the ground.”

But he does have passion for the facility and is no mere pencil-pusher. When no one else can, he checks the runway for debris and at least once cleaned a pile of coyote crap from the runway with his bare hands to expedite a flight. But his approach to problem-solving is admittedly pragmatic.

“I hate to sound like a reformed banker,” he says. “But I think of things as black and white, in terms of return on investment. Here, ROI is anything that helps us with the mission. So a tenant that will make infrastructure improvements is one return. Having a place where our students can get internships or jobs, that’s another kind of return. It’s not just cash flow.”

Kevin Dorton, airport manager, sees the spaceport aspirations as a potential win for TSTC students, the airport and the existing tenants. “I think of things as black and white, in terms of return on investment.”

Joe Griffin

Dorton may seem like an unlikely proponent of a high-risk, almost science-fiction direction for this trade school airport, but he is one of the prime movers trying to transform TSTC into a spaceport.

In early January, Dorton was preparing to head to Fort Worth to meet with state and Federal Aviation Administration officials. They will look over the plans and advise the group on any airspace conflicts that could stop the show. “Sixty percent of the feasibility study is done,” Dorton says. “The other 40 percent is pretty much negotiating and navigating the landmines in the sky. … We have to work with American Airlines and Southwest flights.”

If the FAA doesn’t throw any monkey wrenches into the plan, the feasibility study would be done and the spaceport effort would enter the next phase, the environmental study. If all goes well, in less than three years the feds could clear TSTC’s spaceport for launch.

A space launch at TSTC airport would look like a typical airplane takeoff from a runway. Whether it’s a spaceplane hefted by a “mothership” carrier aircraft, an airplane carrying a rocket or a spaceplane with engines that can reach space, the first step is familiar to any air traffic control tower.

Those aircraft that carry rockets fly somewhere vacant and drop them at high altitudes. Spaceplanes with their own rocket engines would ignite them and fly to space. In both scenarios, the aircraft coming back are landing like airplanes.

The takeoff and landings may be standard, but hosting rockets requires some unique infrastructure and planning. The sweet spot for spaceplane runways is about 10,000 feet or longer, about 2,000 feet longer than Love Field. Airplanes that can launch rockets are as big as airliners, necessitating large hangars. The acoustics of spaceflight need to be considered, especially if the spacecraft will ever break the sound barrier. Most of the extra work is needed to handle propellants – the fuel and oxidizers that power rockets demand specialized storage tanks and security.

That was one unexpected point that arose during Waco’s feasibility study. When Gulliver presented TSTC with a preliminary report, Dorton was dismayed to find that the airport’s “explosives site plan” conflicted with his luring of a new tenant. The spaceport plan demanded a massive, 1,200-foot diameter buffer zone surrounding the fuel and oxidizer tanks, right smack in the middle of what he hopes would be prime aerospace tech park real estate.

“We moved the fueling to the northeast end of the airport,” Dorton says. “While the rockets are fueling, we’ll have to shut down the road to restrict access. But there’s a tenant I am courting now that would have a major footprint, and I’m greedy. I want the spaceport designation and the tenant.”

Even if the spaceplane takes off from somewhere else, a spaceport can only gain by hosting one coming back. The company that operates the craft will need to rent hangar space. If the spaceplane is carrying academic or government experiments, well-equipped labs will be needed to collect and process the cargo. Spinoff companies could form, bringing more tenants to the industrial park and jobs to the county. And any time something novel flies, aviation geek gawkers will come to observe, giving a boost to tourism.

The long-term dream is called “point-to-point” space travel – airplanes that take off, reach suborbital altitudes (you could see the curve of the earth from a window seat), and then land across the globe in a matter of hours. Any spaceport that can accommodate spaceplanes could become a destination for these high-end, globe-trotting flights. The military likes the idea for quick logistics; commercial shipping firms like UPS are intrigued by the potential efficiencies; and rich people eye it as a way to get across the planet in a few hours, cost be damned.

This all sounds cool, and is based on existing projects and programs. Spaceflight is changing, although no one knows how much or how fast. For all the spaceplane developers out there, none is ready for actual paying flights. And it’s unclear when the business might evolve into something stable.

The Challenger Center, opened in 2016, offers simulated space missions for 5th to 12th grade students. Teaching math and science to students is an imperative for economic developers luring aerospace companies.

Joe Griffin

Part of the process of building a spaceport is creating a business plan for why it should exist. So why would a place in Waco want one?

The idea came out of the Chamber of Commerce and its courtship of the aerospace industry. “The Chamber folks used to hit the trade shows and try to land big fish,” says Terry Stevens, a local businessman in Waco and chairman of the McLennan County Spaceport Development Corp. “But we realized we can’t be everything for everybody. So we focused on specific industries and didn’t chase companies that didn’t fit.”

For them aerospace fits nicely. The region hosts a little-recognized cluster of aviation companies, and more than a decade ago these companies formed the Greater Waco Aviation Alliance. Today there are more than 30 aerospace companies counted as members, including flying schools, helicopter charters, defense contractors and Space Exploration Technologies, Elon Musk’s vaunted SpaceX, which operates a facility outside Waco.

The pieces to pursue advanced aviation work seem to be in place: a local aviation business community with a history of banding together, even if they are competitors; a tech school that can stock companies with trained employees; a university-run tech park at Baylor able to handle cutting-edge development projects; an airport with a long runway and tolerant neighbors; a state government with a history of supporting aerospace with grants and low-interest loans; and a Chamber of Commerce that, despite the fact it isn’t funded by sales taxes as in other cities, was ready to jump in and take a risk.

What the plan lacked is someone that actually wants to fly spacecraft. “Usually interest from a tenant is enough for an airport to be interested in becoming a spaceport,” Gulliver says. In Waco’s case, there is no such immediate demand, but they are going for it anyway.

The bet at TSTC airport is that tenants will be enticed by a combination of made-to-order workers, a spaceport designation and good geography, smack in the middle of what some call Texas’ manufacturing and technology corridor. There are more than 1,000 aviation companies within a 500-mile radius.

Waco already draws aerospace companies with its tech students and university researchers. Nothing is more important to the aviation industry in the United States right now than meeting the demand for students focusing on science, technology, engineering and math.

“You can offer all the money [to a prospective company] but if you can’t find employees, it’s pointless,” Stevens says.

In 2015, the demand for welders was sky high in Texas. Not only was the skill set needed in the oil patches and at vehicle manufacturers like Caterpillar, SpaceX needed them to work at their test site in McGregor. TSTC, statewide and in Waco, started a training program to meet the demand. “If six companies approach TSTC with a need, we’ll start coursework,” Stevens says.

The air traffic control tower, where staff handle 101,000 takeoffs and landings a year.

Joe Griffin

The lack of a tenant might seem like a scary thing for an aspiring spaceport, but having a spaceport’s existence depend on the operation of a single tenant hasn’t worked too well for other spaceports. The best known case is Spaceport America in New Mexico, built specifically for Virgin Galactic to fly suborbital missions in air-launched spaceplanes. It cost taxpayers $220 million to build and loses about $500,000 each year, all without seeing a single flight.

A lesser-known dud can be found in Burns Flat, Oklahoma, 90 miles west of Oklahoma City. There, Clinton-Sherman Airport received its launch site operator’s license for horizontal space launch vehicles in 2006. They did this to host a company called Rocketplane, their chief tenant. The company, after taking $18 million in state subsidiaries, filed for bankruptcy in 2010. This has left the spaceport in a lurch, with no clients to take advantage of the license and plenty of taxpayers wondering what happened.

Sometimes, however, even hosting a failed spacecraft program can benefit a newly minted spaceport, as proved by Midland Air and Spaceport in West Texas. The airport became a spaceport – and the Midland Development Corp. spent an estimated $10 million – to accommodate a company called XCOR, which relocated to the airport from California in August. Their idea: create a spaceplane called the Lynx that can take off like a plane, rocket into suborbital space and return to the same airfield. But late last year XCOR changed management, laid off people and focused the remaining team on rocket engine development work that can’t be tested at the airport. The Lynx may never fly, from Midland or anywhere else.

But this loss is mitigated by new business. A company called Orbital Outfitters, which builds flight suits, moved in at the same time as XCOR. The spacesuit makers will be one of the chief customers of the Midland Altitude Chamber Complex, a structure built by the spaceport with $3.5 million of taxpayer money. It has testing equipment for extreme environments that are hard to find outside of NASA labs.

There’s also an easier way to make money off of a spaceport, and it’s so easy that even a billionaire can’t help but get in line for it. In Texas, all it takes is a trip to Austin.

In mid-December, SpaceX’s director of government relations rattled the cup at the state of Texas. At a joint legislative committee hearing in Brownsville, Caryn Schenewerk complained that the Legislature didn’t appropriate any money to its Texas Spaceport Trust Fund. Her company, owned by Elon Musk, is the largest beneficiary of the fund.

“Unfortunately, the Spaceport Trust Fund was not funded in the 84th Legislature,” she testified. “We will certainly be advocating for it to be considered by the 85th.” She didn’t hesitate to call out Florida’s support of spaceflight, which has an infrastructure fund that hands out grants worth nearly $20 million each year.

In 2013 the 83rd Legislature appropriated $15 million to the Spaceport Trust Fund, but the fund is now dry. “All of the appropriated funds have been awarded and no funds are available at this time,” says Sam Taylor, deputy press secretary at the governor’s office. The Spaceport Trust Fund is a good example of economic development or corporate welfare, depending on your point of view of these things.

The first step of the process is to create a development corporation that can solicit and accept taxpayer money.

Here’s how it worked for SpaceX’s spaceport in deep South Texas: Through 2012 SpaceX very publicly considered Georgia, Florida and Puerto Rico for locations of a built-from-scratch spaceport. This ensured a healthy competition of subsidy packages between contenders.

In 2013 officials in Brownsville created the Cameron County Spaceport Development Corp. On the other end, Texas state officials created the Spaceport Trust Fund and promptly routed $13 million to the county’s development corporation. These moves landed the SpaceX deal, much to the lament of Florida and the other contenders. (The state sent the remaining $2 million to the Midland Spaceport Development Corporation, where they devoted the cash to building its aerospace business park.)

The Spaceport Trust Fund money is being spent on infrastructure to support a new vertical-launch spaceport operated by SpaceX on Boca Chica beach, outside Brownsville. Schenewerk this year said the launch site’s existence “is a testament to Texas’ business-friendly atmosphere.”

At the time, Musk said his company planned to invest $100 million into the launch site in Boca Chica beach by 2016. Two launch explosions in Florida have delayed the company’s timetable, however, and SpaceX is still just piling dirt on the beach to stabilize the ground for eventual construction.

Now, Texas politicians are being asked to refill the Spaceport Trust Fund. SpaceX’s 2016 plea for more money has been echoed by the Aerospace and Aviation Advisory Committee, a panel of advisers selected by the Texas governor in January 2016. Sources say they will ask Texas to once again restock the Spaceport Trust Fund in the upcoming budget with a steady commitment of $15 million every two years.

? This recommendation is not surprising, given the makeup of the advisory board. Taylor says the Aerospace and Aviation Advisory Committee includes executives from Lockheed Martin, Bell Helicopter, Gulfstream, Raytheon and Boeing. These players are sympathetic to promoting aerospace capabilities, since many of these companies already have operations at Texas airports. (Raytheon tests military radar from Love Field airport and Bell Helicopter flies experimental helicopters out of Arlington Municipal Airport, for example.)

Military aircraft at TSTC.

Joe Griffin

The advisory committee includes some of the same people who have, or could, receive the Spaceport Trust Fund money they are advising be spent. For example, committee member J. Ross Lacy is the president of the Midland Spaceport Development Board, the recipient of $2 million from the state fund. Gil Salinas is the executive vice president of the Brownsville Economic Development Council and a key supporter of the SpaceX spaceport. Bob Mitchell is the president of the Bay Area Houston Economic Partnership, which has made the Ellington Field spaceport one of its official “economic development issues.”

Waco has a seat at this table as well. A development corporation is the vehicle that rides to Austin to collect these funds. In March 2015, county commissioners approved the creation of McLennan County Spaceport Development Corp. Its address is the same as the Waco Chamber of Commerce.

The county commissioners named seven local politicians and business luminaries to serve. It’s chaired by Terry Stevens, who was named to the state’s Aerospace & Aviation Advisory Committee last January.

He says he doesn’t know if the Spaceport Trust Fund will be funded, as the committee recommended. The vagaries of politics and less-than-expected tax revenue could cloud the fund’s future. “I think it’s a mistake to ever count your chickens and think that the state will have money to give,” Stevens says. “We can do it on our own, but we apply for what we can. That’s a more mature approach.”

If the state doesn’t come through with Spaceport Fund money, Stevens says it’s unlikely that local taxpayers would be tapped to kick in with a bond issue. “I don’t see that anywhere in our plans,” he says.

Dorton, ever true to his banking background, processed the spaceport idea through his usual risk/reward filter, and that meant getting a reaction from the biggest tenant at TSTC airport: L-3 Technologies, a defense contractor based in New York City.

L-3 is Waco’s largest industrial employer and is what Dorton calls the the airport’s “900-pound gorilla.”

More than 1,000 work at the company’s Platform Integration facility. “Platform” in this context usually means airplanes and “Integration” means installing new equipment onto existing aircraft, like 747 airliners and a slew of large military cargo planes, like the C-130 and C-27J. They also work on Navy sub-hunting airplanes like the P-3.

The work L-3 Platform Integration does in Waco has been waning as military contracts withered. This year the company laid off 120 employees in Waco. These losses come on top of 314 reductions made since 2014. This can be attributed to the normal cycle of defense contracts, but it also makes the company eager for new work, and there is one business sector that L-3’s Waco facility has experience with that is expected to grow: spaceflight.

L-3’s facilities at TSTC airport include defense and civilian aerospace work, both of which are visible from this satellite image.

Google Earth

Earlier this year a unique airplane called the Cosmic Girl landed at TSTC and parked inside one of L-3’s big hangars. Richard Branson’s company, Virgin Galactic, bought the 747-400 to convert the airliner into a flying launch pad for small satellites. The company, founded with a focus on space tourism, is now also chasing future customers who want to launch satellites.

Virgin chose Waco for more than its experience with 747s; the Platform Integration staff has worked on previous space programs. The SOFIA airborne observatory – a 747 heavily modified to support a 20-ton far-infrared telescope – is the best known success that has roots in Waco. “These programs are not frequent, but complement the other work we do,” says L-3 spokesman Lance Martin.

The Cosmic Girl project will be done well before the spaceport designation comes to TSTC’s airport, but the work could be a harbinger of future markets for L-3 within the still-nascent private space industry. The contract would be bigger if the converted 747s could conduct test launches from Waco, for example.

“For L-3 Platform Integration, any kind of space-related work that involves horizontal launch would have potential,” Martin says. “Our aerospace engineering and flight sciences expertise would be particularly important for these types of programs, so a spaceport designation would add an avenue for future growth for our division. … We did not approach the Chamber about this idea, but certainly support it as it can benefit the entire community. “

There are other aviation companies that could benefit from the spaceport designation, but none of them are as large as L-3. Absent other tenants with spaceflight aspirations, the hard-won designation could become an unused, expensive piece of paper.

No one at TSTC is seeing SpaceX as a tenant. The company operates an engine test facility in the county, but the company’s proximity has no bearing on the spaceport. Company officials tell the Dallas Observer that they don’t have plans to use the spaceport at all, since they launch vertical rockets, not spaceplanes, although the company supports the idea (as a member in good standing with the Greater Waco Aviation Alliance) and SpaceX officials have toured the TSTC.

Having a spaceport in the backyard could benefit another Waco mainstay – Baylor University. The university operates its own industrial park called the Baylor Research and Innovation Collaborative (BRIC). L-3 rents lab space there, working on advanced composite materials and niche aircraft communications research.

The university, county and aerospace company see these research parks as win-win-wins. In 2014, L-3’s president of L-3 Platform Integration, Nick Farah, spoke to university students about the BRIC. “I want to attract innovative engineers,” he said. “I want to be at the heart of technological advancements. You help me attract talent. At the same time, together we are helping the local economy by attracting and retaining graduates.”

The Greater Waco Chamber of Commerce and TSTC are hoping this ATC tower will one day coordinate the takeoff and landing of spaceplanes.

Joe Griffin

Here’s a hypothetical example, drawn from the kind of work L-3 does but seldom talks about with any specificity. If a sultan wants to install a missile warning system into his private jet, he would approach L-3 for a custom job. L-3 could then use space at the BRIC to figure how to do the job, from the electronics to the carbon composite shell that would surround the new equipment. Program managers could reach out and bring in graduate students to help figure out the details. Those students could then be hired, so that when the next sultan wants the work done, L-3 can offer a strong bid.

How this looks with a spaceport in the mix is hard to predict. In an ideal situation, L-3 would win a contract to develop a space-related project, installing components and testing them during actual launches. This work would spill over into the BRIC, where engineering students would get the chance to get their hands on flight-ready space hardware. When that space-related contract ends, L-3 could have an experienced team, including newly hired students, in place to bid on another contract.

These benefits may not manifest right away, or ever. But the spaceport designation, that hallowed piece of paper from the FAA, makes this type of job possible.

Stevens says the very existence of the TSTC is a testament to ambitious, far-seeing planning. “When they shut down Connolly Air Base in the ’60s, it could have been a disaster,” he says. “But turning it over to become a TSTC school, that was brilliant. … It’s hard to plan 10 or 20 years out, but that’s what leadership is.”

On Jan. 9, classes start again at TSTC. Students spring from on-campus buildings, the walkways become jammed with foot traffic and the cafeteria, staffed with campus-based culinary arts graduates, reopens. This is good news for the guys in the air traffic control tower, who missed the close proximity to what one of them calls “the best burgers in Waco.” It’s also positive for visiting pilots, who can visit the cafeteria during training flights instead of driving for fast food in the airport’s courtesy van.

That Monday afternoon, 90 miles north, Kevin Dorton and Brian Gulliver enter a conference room in the FAA’s Southwest Regional Office in Fort Worth. There are eight FAA officials in the room, and another 10 or so on the conference call, many of them managers of air traffic control systems across Texas. One NASA official in Houston sits in on the call.

Dorton’s plan is to let Gulliver, “our hired gun,” take the lead.

Gulliver opens the meeting with the obligatory PowerPoint presentation. The slides show various spaceplane designs, flight paths of planes and rockets, maps of where the spaceports are and primers on FAA spaceport licensing. But the meat of the afternoon’s gathering is to discuss how a space launch operation could coexist in central Texas’ airspace, along the Interstate 35 flight corridor connecting San Antonio, Austin and DFW.

Every meeting is critical in this process, even an early one like this. For Dorton, it’s the first time he will hear of restrictions and limitations to when and how his spaceport can fly. For Gulliver, it’s a chance to demonstrate how his earlier experience benefits his client. His firm will bid for the contract to do TSTC’s environmental study, the next big step after the feasibility study is done.

The FAA’s concerns are clear. Any launch would have to co-exist with regional flights between cities and longer-haul airliners passing through. The real issue is weather: Airlines reroute aircraft to avoid weather systems, often pushing them over Waco. With every minute in the air burning fuel and taking money away from an airline’s bottom line, anything that takes options away would be met with resistance.

But this airspace deconfliction is not a deal killer, Dorton says later. “All this was expected,” he says. “We may have to restrict our launch times between 7 a.m. and 10 a.m., or launch straight east or west.” Furthermore, air-launched rockets are more flexible when it comes to when and where they operate. “You can just take off and get into a pattern, meshed with ATC, and then go vertical when it’s clear. … We’re OK with that.”

The meeting sounds like a win for Gulliver, too. Like a good hired gun, he doesn’t comment on work he does for clients, but Dorton said he was pleased. “He clearly had a rapport with them,” he says. “They knew who he was and his earlier work. For our part, we were well served.”

The meeting lasts an hour and a half. The path ahead looks like meetings, studies, negotiations, conference calls, check-ins with state politicians, loan applications, zoning plans of a proposed 10-acre industrial park and checks to consultants. The back end of the barnstorming and bravery of experimental flight is bureaucracy and business. For Dorton and the rest of the Waco spaceport dreamers, it’s all the same. It all just looks like the future.

(Adapted from material from a forthcoming book about spaceports, Overlook Press, October 2017.)

The view of Texas State Technical College Airport from above.

Google Earth