Nathan Hunsinger

Audio By Carbonatix

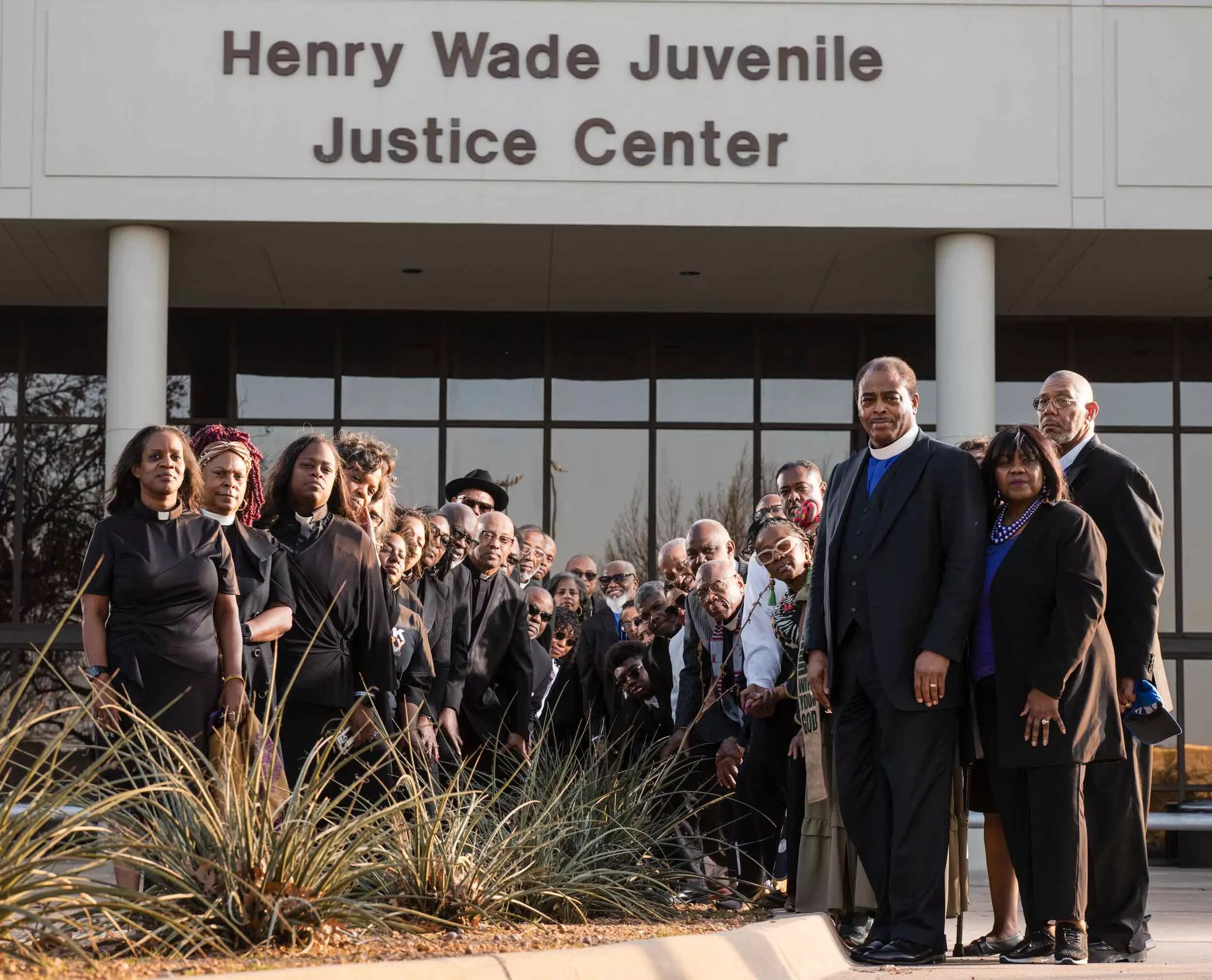

Dallas was hot on Sept. 10, especially at 1 p.m. without a single cloud in the sky. In the parking lot of the Henry Wade Juvenile Justice Center in West Dallas, it seemed to be even hotter with all the asphalt and the absence of shade. The only bit of relief was found near the front doors of the detention center.

That’s where a small crowd gathered to bring attention to yet another damning report detailing a number of failings from inside the building behind them and to demand change. Nearly a dozen members of the Dallas Black Clergy for Safety, Equity and Justice and their partners gathered in a circle, held hands and prayed.

The Texas heat was nothing compared to the intensity of the fury and conviction of those who were praying. One by one, advocates for the incarcerated youths held in the facility spoke to a small assembly of local media. With each turn, the indignation felt by each speaker grew more vivid, more passionate. They were there to speak on behalf of those who could not speak for themselves.

The day before, The Dallas Morning News published a story about a report by the Texas Juvenile Justice Department’s Office of Inspector General that found Dallas County detention staff falsified “observation sheet” documents in an apparent effort to cover up how youths in the center were subjected to unsanitary, unsafe conditions while also being disciplined with excessive, unlawful periods of solitary confinement. The conditions outlined in the report were discovered during a surprise inspection in 2023.

As people leaving and entering the detention center passed by, the Gathering Experience’s Irie Session issued a fiery demand for accountability. Then Marcus King of Disciple Central Community Church said the kids in the center had been “failed by the system designed to protect them.”

The living conditions and treatment of the detention center’s inhabitants wasn’t a story only relevant to a few families of a few jailed juveniles, as far as the advocates were concerned. The message was clear: This issue is about the children of Dallas, about the future of Dallas.

When he stepped to the microphone to bring the press conference to a close, Michael Waters, one of the pastors of the Dallas Black Clergy, called the center a “house of horrors.” He then delivered a knock-out blow to any thoughts that the misconduct and neglect that had been reported on was nothing short of a life or death matter.

Waters described a trip he and his young family took to Charleston, South Carolina. They visited a “separation room” where enslaved African families were split apart after arriving on American shores. He said he was struck by the small size of some of the shackles on display.

Michael Waters, the president of the Dallas Black Clergy, called the Henry Wade Juvenile Justice Center a “house of horrors.”

Nathan Hunsinger

“There were shackles fashioned for children,” Waters said in an urgent way that suggested the trip had been the day before, and not years prior. “I set our 2-year-old, at the time in his stroller, in direct proximity to those shackles, and I can tell you that they would’ve fit. We are here today in many ways because this center has not only treated our children worse than dogs, but in many ways have treated them like slaves. And our heart breaks for our children.”

But the advocates were there not only to bring light to what had happened, but to begin enacting change in how the future would be shaped. Darryl Beatty, the former Dallas County juvenile detention center executive director, had resigned in July. In his place was Mike Griffiths, serving as interim director while the county searched for a new, full-time director.

What Waters and his team wanted was a voice in the hiring process. Somehow, some way. But their collective voice wasn’t welcomed.

Although Waters and his team would meet with Griffiths in the weeks after the press conference, the recruiting process for the new director rolled on without them. Even with the support of Dallas County Judge Clay Lewis Jenkins and District 2 Dallas County Commissioner Andy Sommerman, both of whom serve on the Dallas County Juvenile Board, the Dallas Black Clergy was shut out.

In December, it was revealed that the juvenile board had selected someone to offer the director job to. Lynn Hadnot, who was serving as the Collin County juvenile services director, was the final candidate standing after an interview process that took place behind closed doors. On Jan. 27, Hadnot was officially named as the new director.

Those who had spoken most loudly on behalf of the incarcerated youth for so long went unheard in the months their words were arguably most needed. When county juvenile board officials knew the community was watching, no one was allowed in. Advocates the Observer spoke to are cautiously optimistic about Hadnot’s track record and what that could mean for progress in Dallas County, but the way in which such a pivotal hire was made practically in secret gives Waters and others doubts.

From left to right: Presiding Elder of the Greater Dallas District of the North Texas Annual Conference Juan Tolliver, Rev. Carolyn Brailesford, Bishop Ronnie Elijah Brailsford, Sr., and Dr. Michael Waters are all fighting for change at the detention center.

Nathan Hunsinger

With a juvenile recidivism rate in Texas of around 20% within three years of release from custody as recently as 2022, the notion that a juvenile detention center should be a place for rehabilitation is vital. When a juvenile detention center is mismanaged, allowing mistreatment to occur, the likelihood of the incarcerated experiencing anything close to rehabilitation decreases tremendously, according to advocates.

That’s perhaps the biggest of the many big problems Waters sees when a new report detailing poor treatment of minors behind bars appears. It was certainly a major concern for him when it came to the former director.

“We are not strengthened as a community when we only function with a punitive desire as opposed to being rehabilitative,” he said. “If there was a damning statement that came in this whole process, it came from Director Beatty at the press conference in July when he stated on the record that ‘we are not in the business of rehabilitation.’ That’s a crying shame, and it’s not true. We’re hoping we can continue the work of supporting the deflecting of young people from even arriving at [the detention center’s] doorstep.”

Waters has spoken to a number of individuals, including members of his own congregation, who now as adults still suffer from trauma they experienced in Henry Wade. Waters said many of them feel permanently scarred by their experience there.

The Henry Wade Juvenile Justice Center has had reports of poor living conditions for inmates.

Nathan Hunsinger

That September day wasn’t the first time the leadership of the Henry Wade Juvenile Justice Center had been called out by the state. Going back to mid-2023, reports in the media had brought negative attention to the facility’s management and employees. Former inmates had detailed a number of problems, including an extreme lack of outdoor time while being locked in cells for up to 23 hours a day, as well as a lack of access to showers.

In July 2024, Beatty and other officials denied all allegations relating to poor living conditions and inhumane treatment, including egregious solitary confinement, in the press conference Waters referred to. Just a couple days before that, however, Waters and the Dallas Black Clergy had gathered in the center’s parking lot, with a few umbrellas propped up for a bit of shade, to call attention to assorted stories of mistreatment inside the center, including words from a pair of former Wade inmates who echoed the harrowing stories of mistreatment that had been featured in local news.

In June 2023, The Dallas Morning News interviewed a 17-year-old named Mark Halstead who told the paper that he had only been outside once in 11 months. That was just months after one report found that Dallas County was “locking up minors for months longer than national standards recommend and is doling out more punitive judgments than some other big Texas counties.”

Just a couple of weeks after he issued his sweeping denial of any impropriety at Henry Wade in July of last year, Beatty resigned from his position as the Texas Office of Inspector General opened a new investigation into the center following an unannounced visit by inspectors. Because of a long string of damning reports, Waters and other advocates were hardly surprised by what that state inspector general’s report eventually noted in more detail in September 2024.

What was needed at that point, wasn’t more reporting or more talking, but genuine change. The change, however, wouldn’t include community involvement.

Waters wasn’t looking to conduct any job interviews, nor was he hoping to have a vote or a say in the matter when it came to deciding between one candidate or another. But he felt justified in demanding that serious candidates being considered for the post meet with residents, for the candidates to hear from them.

“We had issued a demand that we be included as a part of the interview process, but that never materialized,” Waters said in December, just after it was reported that Hadnot had been selected for the juvenile board director role. “So we were never brought in to be a part of the process, and that is certainly in keeping with what has been our experience largely throughout this process. We’ve made demands for greater transparency … I also know that [former] Director Griffith had mentioned that in his process of interviewing over the years, he had been a part of a community panel, so this is not a novel idea.”

In late December, it was announced that Hadnot had been selected by the nine-member juvenile board, chaired by Judge Cheryl Lee Shannon. There was no public comment accepted, and none of the candidate names had been disclosed before Hadnot’s hiring was announced. The board wouldn’t make the appointment official until Jan. 27, but the decision indeed had been made.

Although seemingly all of the steps of the hiring process had been carried out without much, if any, transparency, Judge Shannon bristled at the notion of the hire being made in secret when the Observer reached her to ask if announcing the hire after a “closed door vote” was proper. That was one of several questions we asked, but it’s the only one that elicited any response.

“I will respond only to the narrative being advanced that there was some ‘closed door vote,'” Shannon said via email. “This is completely false. The vote was taken as posted and per the Open Meetings Act.”

Technically, the judge is correct. By the letter of the law, the Jan. 27 meeting included a public vote in favor of hiring Handot. But no one is disputing the fact that the decision to hire Hadnot had indeed been made a month before that and the process up until that point was anything but open.

Commissioner Sommerman told the Observer that the decision to not release the names of the candidates being interviewed for the position was made by a majority of the board “to protect the identity of those who had applied for the job,” as such information could theoretically harm the applicant’s present employment. Sommerman was not part of that majority.

“If we were talking about a regular job with ABC Corporation, then yeah, you expect to have a certain amount of closedness to the application process. We all understand that,” Sommerman said. “But this is a public entity, and not only is it a public entity, but it’s one of the most senior public positions we have here, affecting a great number of individuals. It’s the second largest department we have in the county, and it pays a lot of money.”

Sommerman describes the effort to offer more transparency when it comes to the workings of the county juvenile department as “an ongoing fight” and said he is working to “reimagine the board” so that greater transparency in these areas will be less of a battle in the future.

Sommerman also shed light on the process leading up to the Hadnot decision that, again, was simply not transparent.

“The debate about who it should be is what was closed,” he said. “What questions did we ask, what did we consider, are the community’s concerns being addressed and what are the applicants’ positions with regards to what the community concerns are? These are the sorts of things I thought needed to be brought to the forefront and be very open about.”

Sommerman isn’t even sure where the reports of Hadnot being “unanimously” approved as the final candidate came from, thanks to the way the interviews were structured.

“I don’t know if he was a unanimous pick. We never had a vote,” he said. We broke up into groups to do interviews. Me and another member interviewed five candidates. Hadnot was my first pick. He interviewed well, and if he does the things he said he’s going to do, then I’ll be very pleased.”

The Dallas Black Clergy was able to meet with the new director Lynn Hadnot to voice concerns about the conditions at the detention center in January.

Nathan Hunsinger

Sommerman commended the job that interim director Griffiths did in terms of dealing with some of the most alarming issues noted in various reports over the past year or so. But even still, the county commissioner admits there’s a long way to go for Hadnot when he starts.

For his part, Hadnot, who has served as director in Collin County since 2016, sees rebuilding the trust that has been damaged as job No. 1. Hadnot didn’t reply to multiple requests for an interview, but he did speak to WFAA after he was announced as the new director.

“I’d be remiss if I didn’t say the past reports were concerning” Hadnot said when asked about the troubling reports regarding the Henry Wade center. “However, at the end of the day I do know that there is a significant group of stakeholders in Dallas County that are committed to doing this work and doing it at an exceptionally high level.”

Dallas County Judge Clay Lewis Jenkins facilitated a meeting between Hadnot and Waters in early January. The advocates who met with Hadnot liked that the new director said he would be willing to meet with individuals who suffered mistreatment while at Henry Wade.

It was later than when the Dallas Black Clergy wanted to meet with Hadnot, and even though he admits he prefers to temper his own expectations for now, Waters is at least encouraged that the community’s voice will not be silenced when it comes to the treatment of the youth of the Henry Wade Juvenile Justice Center any longer.

“To the extent he could be in our meeting, he [Hadnot] was very open and transparent,” Waters said. “He certainly actively listened to our concerns and I think most importantly, he seems committed to keeping the door open so we can continue in our engagement and dialogue.”