Jim Schutze

Audio By Carbonatix

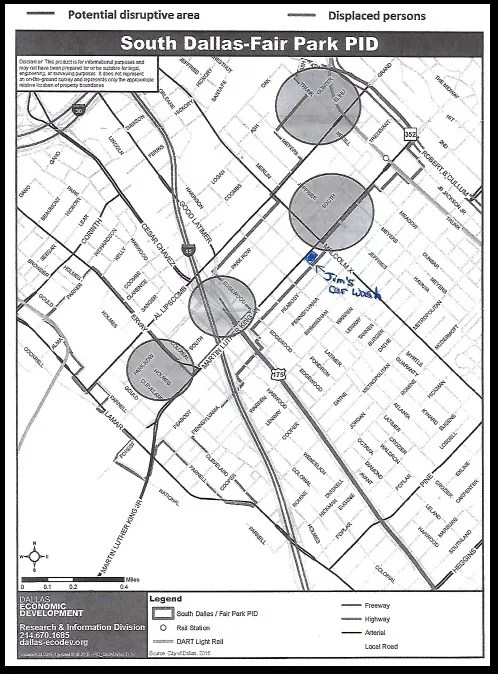

For 15 years, the city’s entire ostensible argument for shutting down Jim’s Car Wash on Martin Luther King Jr. Boulevard in South Dallas has been that the car wash is a hotbed of crime. But the city made a big mistake two weeks ago. They published a map of the hotbeds of crime on MLK in South Dallas. Guess what? The car wash wasn’t on the map.

“We’ve had a history of crimes against persons, a history of drugs, history of alcohol, assaultive-type offenses at this location.” — Dallas Police Major Vincent Weddington

Everything else was. If anything, the map based on police statistics showed the car wash as an island of calm in a sea of crime.

People from the city attorney’s office handed out the maps at a meeting of the South Dallas-Fair Park Public Improvement District. One of the people in attendance who got a map from the nice people in the city attorney’s office was Dale Davenport, co-owner of Jim’s Car Wash. He was very glad to get it.

Davenport was glad to get the map showing his car wash was outside the known crime hot spots, because the very next week he had to go to court where people from the city attorney’s office were going to argue his business should be shut down because it’s a crime hot spot. This is something I have been writing about for 15 years.

In 15 years, a zillion conspiracy theories have emerged to explain why the city has expended what by now must be hundreds of thousands if not millions of dollars in in-house attorney salaries and outside counsel fees to shut down this car wash. The real reason.

I have my own conspiracy theory, which I will explain to you in a minute. I’m not bragging on myself, but I should tell you that when it comes to conspiracy theories I really am what I would call a professional. So hang on.

Davenport was suing in the 14th District Court of Judge Eric V. Moyé to persuade Moyé to overturn a verdict by the city’s zoning board of adjustment. The board of adjustment had ruled that the car wash is a nuisance and Davenport and his father have made enough money from it already, so it should be shut down.

The members of the board of adjustment are citizen volunteers, few of them lawyers. During Davenport’s hearing, which I attended, a woman on the board said she thought the car wash should be shut down because it has bright lights and she lives near some tennis courts in North Dallas that have bright lights and she can see them from her house and it irritates her. That’s about the level of jurisprudence that takes place.

In Moyé’s court earlier this week, the city, as it always does, put a city cop on the stand to testify that the car wash is a terrible, terrible hot spot of crime. Dallas Police Major Vincent Weddington told the court, “We’ve had a history of crimes against persons, a history of drugs, history of alcohol, assaultive-type offenses at this location.”

As always when the city puts police on the stand to testify to the hot spot thing at the car wash, Weddington came to court without any statistics – not a single police report. He forgot to mention that the entire area around the car wash is awash in crimes against persons, drugs, alcohol, assault and prostitution.

Weddington left out that the Davenports have done every single thing the city has ever asked them to do to fight crime, including installing security cameras and 24-hour bright lighting at no small offense – something few of the neighboring businesses have done. The lights were not for tennis.

Imagine how thrilled Davenport was when people from the same city attorney’s office the week before had handed him that hot spot map at the South Dallas-Fair Park PID meeting. Davenport attended the meeting, by the way, because he was one of the founders of the PID, which was set up to raise money for private guards and increased security in the neighborhood.

The PID had been a bit of a hot spot itself for a year or so. Not long after Davenport helped get it up and rolling and after the PID had collected a special tax on neighborhood businesses to the tune of six figures, a City Council member had management of the PID “privatized,” turning the PID’s checkbook over to an entity she was familiar with called Hip Hop Government.

When Davenport asked where the security guards were, he was told someone had hip-hopped away with the six figures, the cupboard was bare and there would be no guards. Since then the city attorney’s office has shown no inclination to find out who hip-hopped away with the money.

The PID meeting two weeks ago was to announce that the PID now has new tax money in its checking account, oh joy, and is ready to hippity-hop at it, again. “In other words the PID is back in action,” Davenport told the court.

Luckily, Dale Davenport held on to his copy of the city’s MLK crime hot spot map before the city had a chance to purge it from the city’s website. The inked notation is Davenport’s, showing the location of his property.

Dale Davenport, City of Dallas

The hot spot map was just what Davenport needed to refute Maj. Weddington. The PID meeting was intended to show where money was needed for added security. Not at Jim’s Car Wash. Davenport told the court the map was now available on the website for the South Dallas-Fair Park PID.

“A gentleman who’s an attorney with the city of Dallas that’s setting on the back row over there. He was also there.” — Dale Davenport

Davenport’s lawyer, Warren Norred, asked him to say who had been present at the PID meeting when the hot spot map was handed out. Davenport named a community prosecutor, whose name he may have gotten little wrong, but he added a person of whose identity he seemed certain: “A gentleman who’s an attorney with the city of Dallas that’s setting on the back row over there,” he said, nodding to the back of the courtroom. “He was also there.”

I craned to look and saw a guy in the back of the courtroom sort of ducking.

But another city attorney was on her feet already objecting to the introduction of the city attorney’s own hot spot map as evidence. Moyé cut Davenport off brusquely: “Just a minute,” the judge told Davenport. “When you see counsel stand up, I want you to stop speaking.”

He did.

The attorney for the city said the map was not relevant because it was devised after the city’s proceedings against Davenport had already begun. “This is a document,” she said, “that was printed after the Board of Adjustment (hearing).”

So, wait, this was a big stop-dead, slap-my-mouth non-lawyer moment for me. I have no doubt there’s a lawyer thing about new evidence and old evidence and when evidence can be introduced and so on. I’ve seen that on TV. And far be it from me to question TV.

But is this not the whole thing? Like, the entire thing? The entire reason for shutting down Davenport’s car wash is that it’s a crime hot spot. The people in court telling the judge it’s a crime hot spot are the city attorneys. Now here is a map that was handed out by city attorneys proving that the car wash is not a hot spot.

So if there’s a lawyer thing that says this evidence cannot be introduced, shouldn’t it be undone or something? There were half a dozen city attorneys in court that day. There should have been some way they could all have slapped themselves in the mouth like The Three Stooges – slappety-slap – and said, “Oh, damn, this is all exactly upside down, unfair and wrong, and we’re the ones who proved it.”

The Three Stooges

NBC Television re-1978 Wikimedia Commons

So you know what they did instead? That evening after court adjourned, they took the hot spot map off the city’s website. Maybe it will be back up after this column appears, but when I looked yesterday, the hot spot map was nowhere to be found on the South Dallas-Fair Park PID webpage. And they think that makes it all right, I guess. Shut the guy’s business down for what you know is a lie. Just take the evidence of the lie off the webpage.

That’s what happened. Moyé zoomed right over the whole issue of the hot spot map, sided entirely with the city, refused to set aside the board of adjustment ruling and slapped Davenport with even more onerous requirements that will make it impossible for him to reopen his business anyway. He’s screwed.

My conspiracy theory. Forget who wants this property. It’s somebody. We’ll find out someday. That’s not even important yet.

This is what is called a taking. The city doesn’t want to force Davenport to sell his property through the normal legal process under the laws of eminent domain. But it wants him to sell. The combined effect of the Board of Adjustment verdict and Moyé’s ruling will make it too expensive for Davenport to hold the land, which he estimates will now cost $2,000 a month, while the property produces no more income. He will have to sell to somebody.

Couldn’t he develop the property as some other kind of business? Maybe. But this is a very difficult place in which to do business. The car wash works. Something else might not. Why should he have to roll the dice when this is working, and why does City Hall get to tell him when he’s made enough money from his investment and hard work?

On the other hand, if the city had a legitimate need for this property, defensible under the law, the city could take it by eminent domain. But those laws would require the city to state its purpose publicly and then go through a series of steps. All of those steps would be visible to the public.

A price would be set. If it came to it, Davenport would be compelled by law to sell at that price. But at least along the way the laws of eminent domain would have provided Davenport and his lawyer access to the rule of law and ancient rights of property.

The conspiracy here is not in who but how. Why would the city lie and say it’s forcing Davenport out of business because his place is a crime hot spot when the city obviously knows from its own research that that is untrue?

The answer is that the city doesn’t want to get the property through straight-up eminent domain. It wants to take it. Somewhere in eminent domain – the public purpose, the price, the disclosures – some trap lies waiting, something the city cannot or just will not do.

This is called a “taking,” not eminent domain, because it lacks law. It lacks truth. It lacks honesty. This is a taking because it is theft.

It’s public theft, and if it is allowed to stand, not a piece of property in this city will be protected by property right. If they can steal his, they can steal yours. They can do anything.