Wikipedia Commons

Audio By Carbonatix

Now that the Dallas-Fort Worth metro area is on the list of 20 finalists for the new Amazon second headquarters, I feel compelled to offer two observations: First of all, there is no such thing as a second headquarters.

Companies are like people. It is in their nature to have only one head. If they have two, they will be too scary for the midway. The crowds will run screaming in the other direction. The thing Amazon builds will not be a second headquarters. It will be a regional, divisional or satellite headquarters.

And that’s great. So what if it’s not really a headquarters? Instead of HQ2, which is what Amazon wants to call it, we can just think of it as HQ/2, with the two as a divisor rather than a multiplicand. Makes more sense anyway.

Amazon says it will spend at least $5 billion building HQ/2 and will create 50,000 new high-paying jobs, which brings me to my second observation. Maybe not an observation so much because it’s probably way over my head, but a simple question: There has to be some price too high for a local community to pay in order to get HQ/2, right? At least theoretically?

Sure, it’s a ton of jobs and tax base and prestige and all of that wonderful stuff. But we would balk if our local elected officials told Amazon not only would the company never have to pay any taxes, but Amazon officers also could have their pick of the first-born sons and daughters in the region to keep as concubines.

Too much, right? There would be grumbling. We might ask, “Will they get health care?” An incentive offer like that would at least raise an eyebrow or two.

What did I say, two observations? OK, three. Here’s the third, which I promise will be my last: In terms of what’s going on in the bidding war so far nationally, no one yet is quite at the level of youth concubines, but we are definitely headed in that direction.

Raleigh, North Carolina, has offered to chip in $50 million for construction, plus every person who gets a job as a result of HQ/2 coming to Raleigh will get a 100 percent rebate of all North Carolina state income taxes for 25 years. Plus, somebody will pay Amazon $5,000 for every new job it creates. Somebody rich, I guess. So, wow, who could beat that?

Denver could. It’s offering $100 million, plus-plus-plus the other stuff, too. Who could beat that? Los Angeles. $300 million to $1 billion on a sliding scale.

Who could beat Los Angeles? Atlanta: $1 billion, no slide, just come and get it. How do you beat that? Chicago, $1.7 billion. Columbus, Ohio, $2.3 billion. Philadelphia, $2 billion to $3 billion, sliding scale. But better: Montgomery County, Maryland, $5 billion plus tax cuts, no slide, come and get it.

If you’re Newark, what does it take to get somebody to spend the night at your house? Seven billion dollars.

And the leader so far, the place that comes closest to offering its first-born sons and daughters? That would be Newark, New Jersey, with a bid of $7 billion, by far the fattest in the country that we know of and, unsurprisingly perhaps, the brainchild of New Jersey’s still-governor-somehow, Chris (The Beach Boy) Christie.

If you’re Newark, what does it take to get somebody to spend the night at your house? Seven billion dollars. And is that even something we should want to beat?

Our offer, by the way, is still top secret. You might want to lock the kid in the garage until we find out what’s on the table.

Professor Nate Jensen at the University of Texas at Austin is co-author of an upcoming book on this question – how much is too much? One of the very interesting findings he and his colleagues have turned up is that a majority of business relocation decisions are baked in before companies even start ginning up their so-called location competitions. It’s kind of like, “OK, we’ve already made up our minds we’re moving to Spot X in the State of Sawsandsuch. Now let’s see how much money we can gouge out of the locals by pretending we might not come.”

In analyzing a state of Texas incentive program called Chapter 313, Jensen concluded that between 85 percent and 90 percent of the companies that received incentives for locating in Texas under 313 would have located in Texas anyway, even without the incentives. His best case involved Amazon.

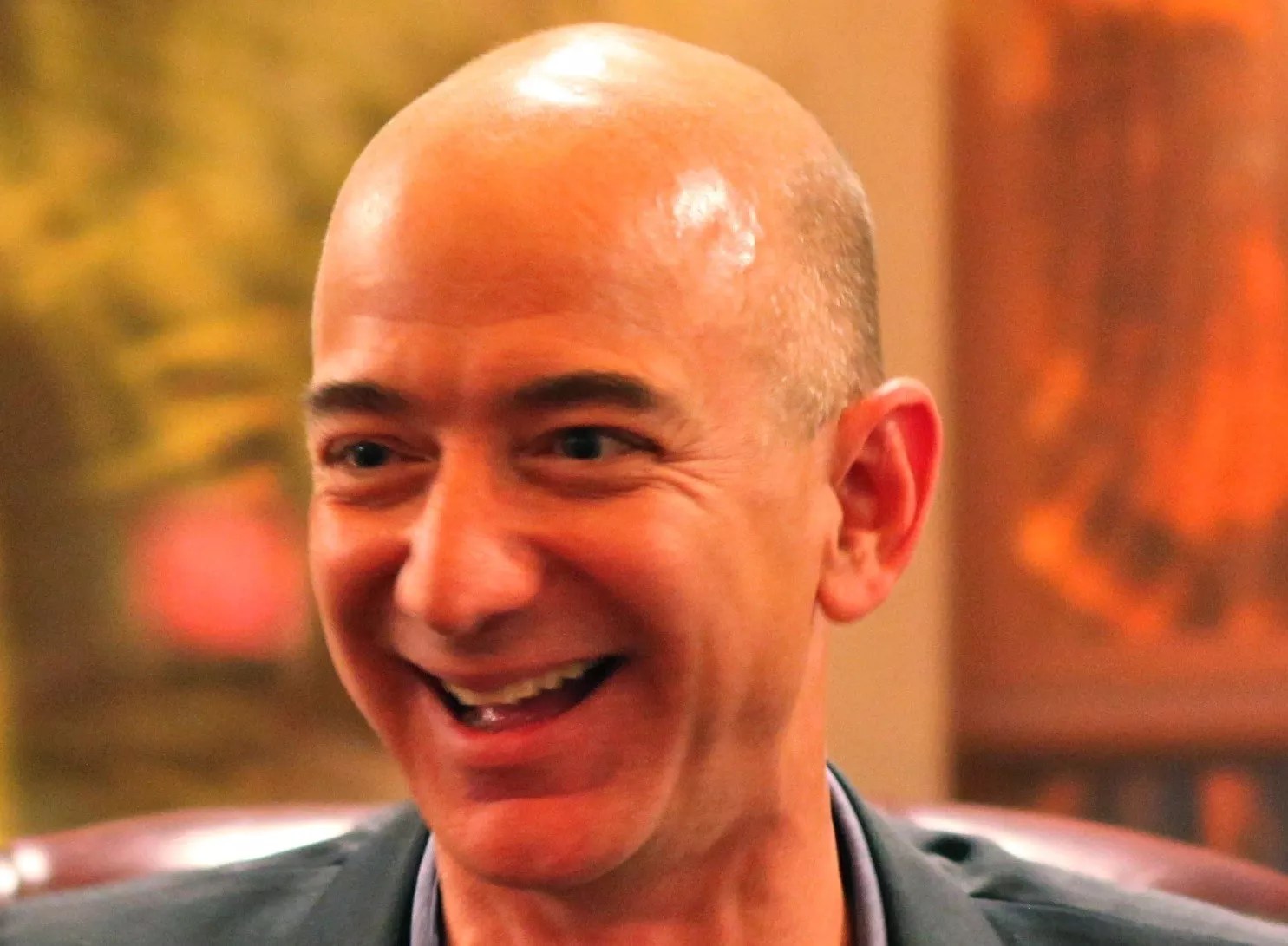

Last fall, Amazon CEO Jeff Bezos broke a bottle of Champagne over a windmill in a giant wind farm in Scurry developed by Amazon, big enough, supposedly, to power 90,000 homes. Bezos won generous local and state Chapter 313 subsidies for the project by swearing that the subsidy was a “determining factor” (language in the law) in deciding where the would put his wind farm.

But as Jensen explains, Bezos also beat a federal deadline and collected another fat tax break by swearing at the same time to the feds that his wind farm was already under construction in Texas. The Texas comptroller took a look at all of that and found evidence that the wind farm was already locked in at Scurry when Bezos said he was still making up his mind. Then, in typical Texas fashion, the comptroller gave the state subsidies full approval anyway.

I asked Jensen how a government agency could know if a company seeking an incentive is playing games. He said, basically, it can’t.

“This is the ‘information asymmetry’ we talk about in academic studies of incentives,” Jensen said. “Companies have full information on the factors that matter for their decisions, and governments only have limited knowledge what will matter for the firm.”

When it’s all said and done, Jensen says, the incentive money local governments give away is often hugely expensive for governments but relatively peanuts to the companies that get the incentives. He cites a study in North Carolina that found that 70 percent of corporate executives who had been granted state incentives were not even aware they had received them.

Long-term incentives – money promised over decades – is especially not interesting to many people in business, Jensen says, because few companies last long enough to collect and people in business know how hard it is to predict events that far out. The North Carolina promise of a 25-year tax break, in other words, might as well include a proviso, “unless the Chinese take over.”

Are we playing Texas Hold ’em with Amazon or you-strip-I-watch poker?

Dmitri Ma Shutterstock

I said, OK, say this is high-stakes poker. The rules are that the businesses can look at our cards, but we can’t look at theirs. Why on earth would we play?

He said the upcoming book addresses that question. “We did some survey work on this. What was interesting to us was that there seems to be motivation for elected officials to give incentives, even if they are not important to the companies relocating, because it’s a great way to take credit,” Jensen said.

At the end of that game, he said, some elected official will be on TV handing a giant Publisher’s Clearinghouse-sized check to a CEO and taking full credit for landing the relocation.

“A big chunk of our book is about credit-claiming,” he said, adding that there seems to be almost no downside for politicians in giving away the company store.

I can attest to that. I see it all the time in covering City Hall. The city gives away hundreds of millions of dollars a year in tax incentives without the slightest idea what we’re getting back for it, and then people can’t figure out why the city can’t fix the streets. But nobody ever makes the connection.

“There seems to be motivation for elected officials to give incentives, even if they are not important to the companies relocating, because it’s a great way to take credit.” — Nate Jensen, UT professor

Here is an interesting wrinkle in our case in Dallas. Our new city manager, T.C. Broadnax, recently trotted out a new high-tech tool for analyzing incentive deals called Market Value Analysis. At least theoretically, it should be possible to take whatever it is the Dallas-Fort Worth region is offering, put it in Broadnax’s MVA and find out whether the deal would be worth it to us.

Of course, depending on what that answer is, Broadnax’s new machine also could make the elected leaders who are his bosses look like financial nincompoops. I was unable yesterday to provoke an answer from Broadnax about whether he will use or even offer MVA as a tool to determine how much of the store we should give away to Bezos.

On the one hand, I can understand Broadnax feeling shy about this. He may not want to be the one to critique the emperor’s new clothes.

On the other hand, this clearly is the biggest decision of this sort that Dallas will have to make for a long time coming. If using the new MVA tool is too risky for the city manager in this case, then I don’t know why anybody should take it seriously in any other situation.

Is MVA only for analyzing little deals and little people? When it’s Bezos, does the thumb go down on the MVA scale?

Nobody denies that HQ/2 could be a great deal for some city. But it could also be a terrible deal. If we have a way to find out what it would do for us, not using it seems pretty crazy. Or is the tool just not that good?

It comes down to a simple truth. We can offer a little too little or a little too much, or we can be total idiots. Guess which one I’m betting on.