Illustration by Alex Nabaum

Audio By Carbonatix

A bill that will codify a definition of consent into Texas law was signed by Gov. Greg Abbott on Friday, signaling a step forward for sexual assault survivors and advocates across the state.

The bill was named the “Summer Willis Act” for a Texas woman who says she was raped at a University of Texas fraternity party a decade ago. While Willis did not pursue legal action at the time, she later discovered that her assault would have been difficult to prosecute under state law because she was not given alcohol directly by the person who raped her.

“[My rape] doesn’t count, one, because I voluntarily took a drink and two, because that person, when I entered the party, did not have the intent to rape me, even though someone else did,” Willis recently told PBS. “I think something cracked inside of me, realizing that, even if I wanted to, even if I went to the police the next day, they would have just turned me around.”

There is no federal definition of consent, and before House Bill 3073, Texas defined sexual assault “without the consent” of the other person as instances in which physical force was used to facilitate the assault, cases in which the victim was unconscious and cases in which the victim was mentally disabled or incapacitated in a way that they could not have given consent.

What consent actually meant, though, was legally vague. That made instances where a victim was unable to give consent due to drunkenness or other inebriation tricky to prosecute, Amy Jones, CEO of the Dallas Area Rape Crisis Center, told the Observer.

“We have seen this time and time again, where so many survivors come to us and their story is, ‘I was at a party, I had too much to drink.’ And … then they experienced some sort of sexual assault. And they would fall through the cracks,” Jones said.

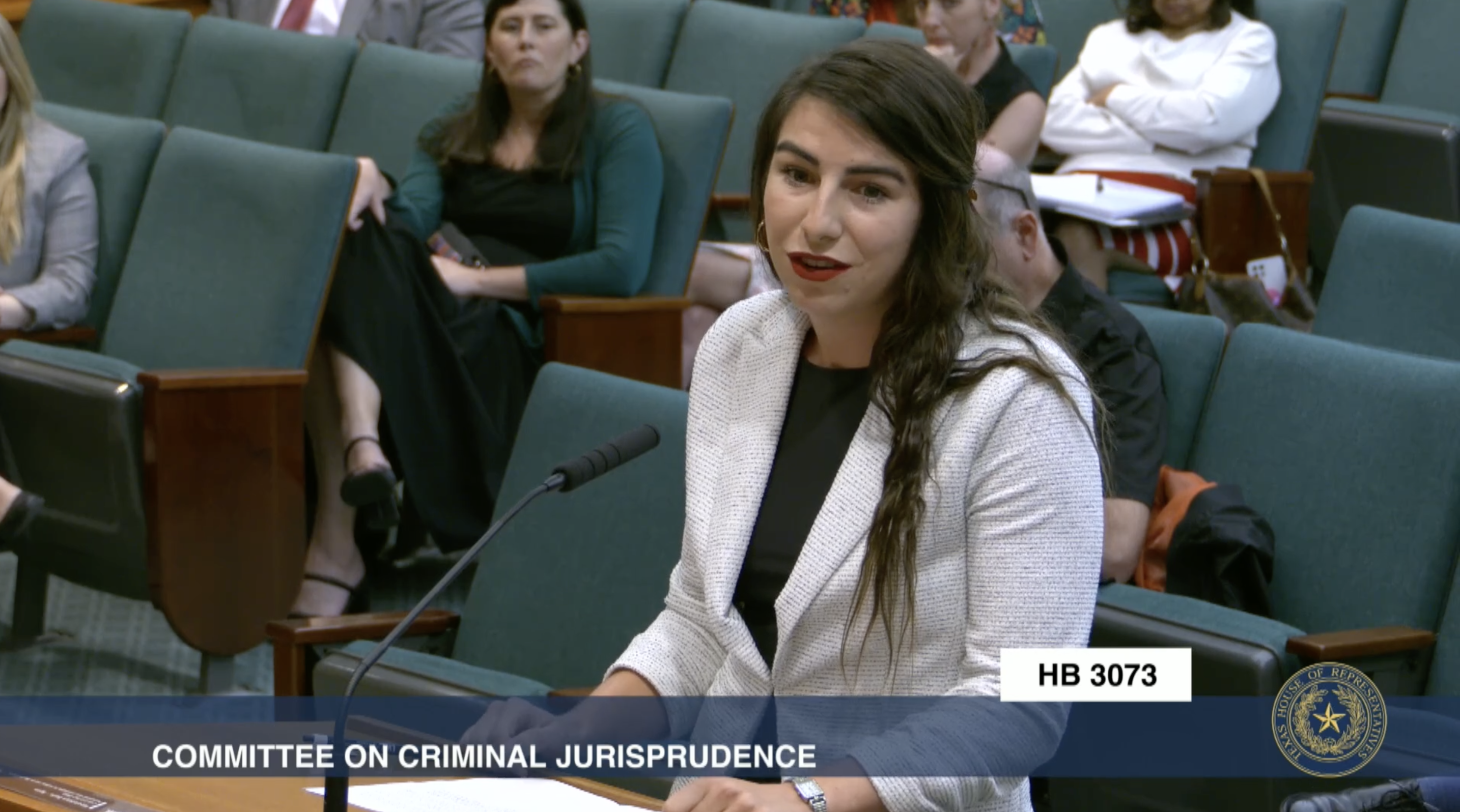

Summer Willis testified before the House Committee on Criminal Jurisprudence in April, asking state legislators to close a loophole that has kept survivors from getting justice in sexual assault and rape cases.

Texas House Livestream

With the passage of the Summer Willis Act, the legal relationship between consent and sexual assault has been broadened to include cases in which a person is too drunk to knowingly say yes to sex. The act brings the legal understanding of consent into step with the cultural understanding of it, and the bill will go into effect Sept. 1. Jones said that timing could be crucial ahead of students returning to college campuses.

According to the Rape, Abuse and Incest National Network (RAINN), 13% of students across graduate and undergraduate programs experience rape of sexual assault while on campus. Over 50% of those assaults take place over the fall months, and students experience an enhanced risk of victimization during their first year at school, the network reports.

“Perpetrators of sexual violence look for vulnerabilities to exploit, which is why the number one date rape drug is alcohol,” Jones said. “For this loophole to be clarified, I think, is really important. And I think it sends a message to survivors that we understand what sexual assault actually is.”

Jones described Willis’ championing of the bill as “instrumental” in helping pass the legislation that advocates have long sought.

Between 2023 and 2024, Willis gained fame for her decision to run 29 marathons in a year with little training to raise awareness of sexual abuse and funds for RAINN. During one of the marathons, she ran while carrying a 45-pound mattress to symbolize the weight survivors of assault carry with them.

“I know there are concerns about what happens when both parties are impaired by alcohol, but let’s be clear. Alcohol did not pin me down. Alcohol didn’t ignore my incapacitated state,” Willis said while testifying before the House Committee on Criminal Jurisprudence in April. “There is a chasm of difference between a regrettable choice and predatory violence. Alcohol does not get to be a get out of jail free card.”

For Jones, the passage of HB 3073 was a significant win. However, there were a few bills the state Legislature failed to pass that she hopes could gain momentum in two years when the next session convenes.

One of those would require facilities that conduct SANE exams, the forensic examination that occurs after a victim has experienced sexual assault, to provide access to emergency contraception following the exam. Another would have clarified how crime victims’ compensation is applied to assault cases to ensure survivors don’t get footed with an emergency room bill after getting a SANE exam.

Still, Texas is ahead of many states when it comes to protecting survivors. According to RAINN’s consent law tracker, which was last updated in 2023, 35 states did not define consent within their statutes. On Sept. 1, Texas moves off that list.

“I anticipate we’re going to see a lot more cases taken to the grand jury,” Jones said. “I’m really, really hopeful.”