Photo-illustration by Sarah Schumacher; Photos by Jessica Patrice Turner; Getty Images; Adobe Stock

Audio By Carbonatix

The women of Ravinia Heights hate their new neighbors and they’ll do anything to get them out of their neighborhood.

Thick mud squelches under the nails of the sticky fingers of architects molding the day’s mud pies. The sun beams down on the children, ages 3 to 11, playing in the backyard of the house at the end of Alden Avenue in a quiet corner of Oak Cliff. Later in the day, under a canopy of trees in the backyard, the group of 13 children will extend their small and dirt-speckled hands to the sky, before folding flat at the waist, keeping their vertebrae in line, and finally heaving forward with an exasperated sigh, catching themselves on their tiny palms and moving their sitting bones towards the sun. The children, under the instruction of the on-staff yoga teacher, have become miniature yogis themselves.

On other days, they will receive lessons in natural fiber dyeing, where they will wring cloth until it takes on new colors. They’ll learn herbal remedies based on Eastern medicine, also known as Ayurvedic wellness. They’ll roll in the dirt in jiu-jitsu self-defense courses. They’ll hopefully learn all the obvious cruxes of a well-rounded primary education and key elements of their holistic learning environment.

The children, with no open spots available, attend Caleidos, a $15,000 experimental learning environment, legally designated as a “learning pod,” and specifically designed to comply with the minimum homeschooling requirements, and little else. There, they learn the types of skills that are often not taught to kids.

Monday through Thursday, from 9 a.m. to 2:50 p.m., the back door revolves as children rush in and out between three blocked “nature play” sessions and basic lessons in math and grammar, complemented by integrated artificial intelligence lessons infused with an outdoorsy feel. It’s all part of the curriculum, “rooted in connection and nature,” according to the school website. The children won’t take standardized tests, and they don’t have grade levels either. Their academic success and progress are measured by a “child-centered” approach that recognizes their “unique learning journey,” in their words.

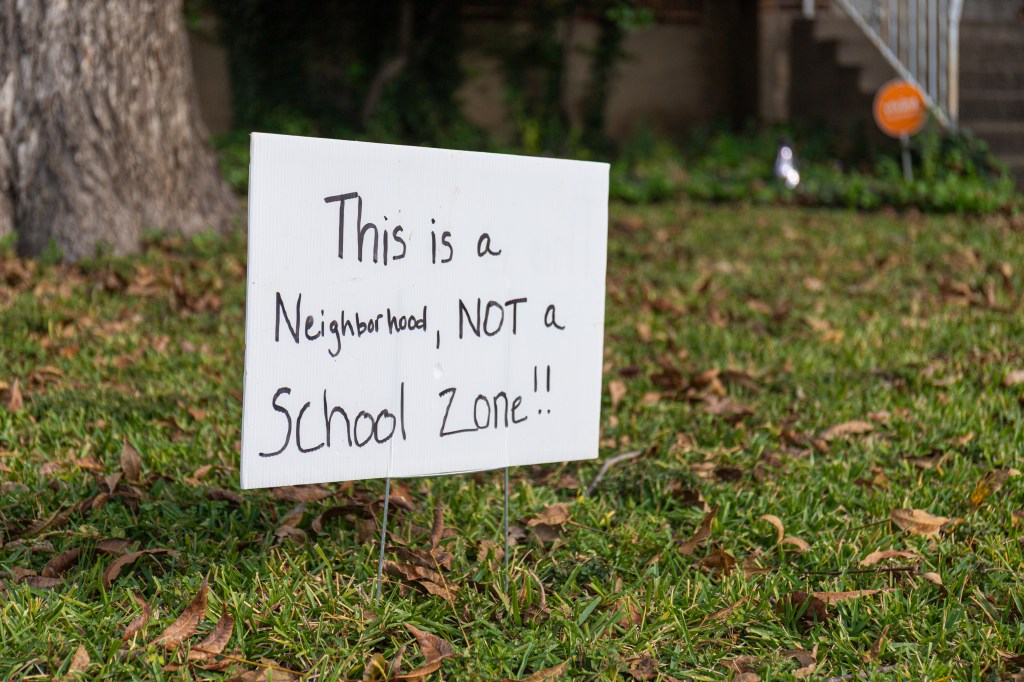

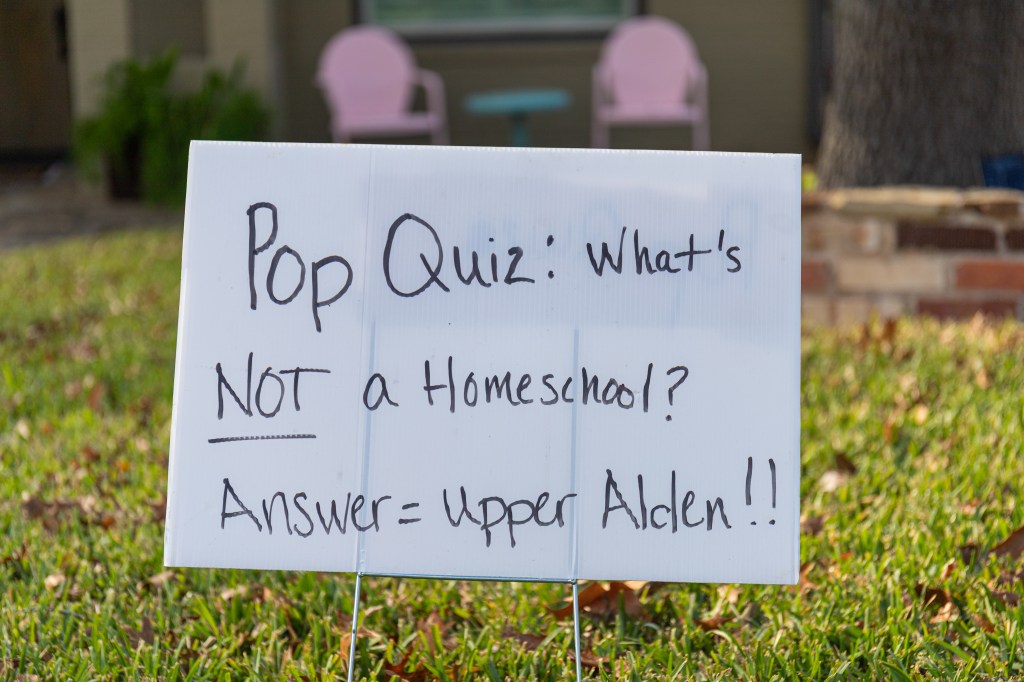

Just a block away, women convene on a porch, whispering about the learning pod they believe is operating illegally as a microschool at the end of the cul-de-sac, strategizing their next move to shut it down after all their previous attempts have failed. What about calling the fire marshal again? Is it worth contacting their City Council member? Did anyone hear back from that state representative? And what can we do to get these people out of our neighborhood?

Caleidos doesn’t claim to be a school, and legally, it isn’t doing anything wrong. An education law passed during the pandemic offers it immunity from the standard protocol of city zoning regulations. Still, a diligent group of longtime neighbors who want to keep their streets strictly residential wants to see the end of Caleidos. But state law has tied the hands of local elected officials. That likely won’t stop the team of neighborhood sleuths from exhausting every resource they have, even if it means years of work, until school’s out forever.

Jessica Patrice Turner

The Longest Spring Break Ever

At thousands of schools across the state, the bell rang on Friday, March 13, 2020, and a spring break that seemed to have no end began. COVID-19, still in its early stages, was sweeping the globe, and the conveniently timed break from school was an exciting reprieve before the maddening, systemized isolation would begin. At that point, no one yet knew that in-person classes would not resume for the remainder of the school year. No one knew that, even for just a few weeks, every student would be isolated from their peers, without extracurricular activities and recreational opportunities.

As the spring of 2020 rolled toward the summer, some parents found alternative routes to enrich their children: learning pods. The family-led organized meetings to share academic resources and pursue tutoring helped establish some sense of normalcy for children in unprecedented times. Learning pods functioned much like the co-ops that have been a crucial element of homeschooling for years. However, at the time, organizing was passé, and cities with strict social distancing ordinances, such as Austin, attempted to regulate learning pods using city zoning codes and existing school guidelines.

Cue former Rep. Larry Taylor, a Republican from Friendswood, who drafted a short but mighty bill, the Learning Pod Protections Act, that offered near-impenetrable protections to loosely defined learning pods. Per the law, which soared through both chambers and nearly caught wind as it flew off of the governor’s desk with a signature, a learning pod is any-sized group of children who meet at various times and various places to participate in or enhance learning, sometimes for the exchange of money.

To be clear, the law clearly forbids government entities from obstructing a learning pod.

“A learning pod is exempt from any ordinance, rule, regulation, policy, or guideline adopted by a local governmental entity that applies to a school district campus or child-care facility, including any requirements regarding staff-to-child ratios, staff certification, background checks, physical accommodations, or building or fire codes,” it reads.

The law also prohibits any investigations from any government bodies if the body “would not have initiated or conducted the inspection, investigation, or visit if the learning pod did not meet at that location.”

Learning pods do not have to be registered in any database, nor do parents have to disclose whether their child is enrolled in one. It would seem that the only requirement is that the pod meet at varying locations and times, which can be easily achieved through field trips.

However, the overarching bill, drafted in the context of a global shutdown, is now being used by Caleidos to circumvent the typical Dallas zoning laws that would otherwise forbid a school from operating out of a residential home. And it’s making quick enemies of their neighbors.

Jessica Patrice Turner

The Women Of Ravinia Heights

The women of Ravinia Heights, a few streets with centennial single-family homes now worth more than they had ever imagined, enjoy the community they have crafted. In their tiny sphere, everyone knows everyone and their dog. They like it that way. They like morning “hellos” to the porchside bird watchers they call neighbors, and the summer night chats over the fences with the scents of grilling hot dogs wafting through the air. So when the house at the end of Alden Avenue sold in August 2024, they got a fishy feeling.

“It’s infuriating,” said Nicole Neises, who lives on a cross street to Alden Avenue. “We have a great community here. We just had a block party for our homes turning 100. All of the neighbors we are friends with came. We’re just that type of neighborhood.”

The Caeidos house seemed to remain vacant, or at least, empty at night, but soon a steady stream of cars cycled through in the morning and midday. Eventually, some neighbors would meet the new tenants, Dr. Caroline Lee and Melanie Guerra, the co-founders of Caleidos, neither of whom lived at the property, which was owned by Thani Burke, a Dallas Realtor who also owned another home just a few doors down on Alden Avenue.

Community building and involvement are important to Caleidos, according to its messaging, but the women of Ravinia Heights disagree. Burke did not respond to interview inquiries.

“They gave out welcome packages, little baggies to all the neighbors on Alden, saying, ‘We want to join hands with you as a community.’ Well, you know what?” Neises said. “You would have joined hands with us as a community when you knew your business plan, not the week before your school opened.”

Neises and the neighbors who share her concern have lived in Ravinia Heights for years and intend to stay for many more. They are wary of their community being purchased and converted for business development by an entrepreneurial Realtor, similar to what happened in Bishop Arts or what’s happening in Elmwood. It’s a typical tune for much of Oak Cliff, which is tired after years spent as the gentrification headquarters of Dallas.

“It’s just so exhausting,” said June Askew, who lives a few doors down from Neises. “We have to protest our taxes every year. We have to go to these [City Hall] meetings, sign these petitions, do all this stuff. This is our home. Who are these people? Why do they get to stay?”

Jessica Patrice Turner

Zoning Immunity

Current zoning laws impose strict mandates for home-based businesses, including size and location requirements, employee and parking restrictions and a number of other regulations that address the general effect on the neighborhood, ranging from odor to noise to traffic. While home-based businesses are certainly possible in the city, they are not easy to maintain in compliance with the city code. Unless, that is, your business is immune from most code enforcement on building use thanks to an all-encompassing bill passed when legislators were still wearing masks.

The half-dozen women, mostly concerned about the fate of their neighborhood, are more than a little bit ticked about people using loopholes while also being curious about the efficacy and legality of such a unique educational format. They say that they have waved every flag they can, hoping Caleidos will at least be suspended, if not shut down.

“I’m a rule follower, so right there, I’m already jacked, because it’s just not right,” Askew said. “We can go into the ifs and the whys and the this and the that, but it’s just not right. You’re operating a business in a residential area, and then you add children. There are no regulations. There’s nothing.”

Neises says she attempted to report the school to the county fire marshal, but even that was futile in the face of the expansive law, which allows learning pods the rare exclusion from building and fire safety codes. A tip to the Department of Health and Human Services proved useless, too, and the tipster was directed to the statewide abuse and neglect hotline within the Department of Family and Protective Services. By now, the women are used to redirection, being referred to a new department or a new lawmaker time and time again.

Chad West, the City Council member overseeing their district and one of the earliest to field complaints from the neighbors, said there’s little that can be done about it locally.

“Unfortunately, Chapter 27, Sections 001 and 002 of the State’s Education Code preempts the City from investigating or enforcing school or child-care facility regulations on learning pods,” West said in a statement provided to the Observer. “Because of these state-level restrictions, we have connected residents with Representative Jessica González’s office to explore potential legislative solutions to close this loophole.”

While learning pods have numerous workarounds, they are still subject to the city’s standard parking and noise ordinances. So far, however, his office has only received one complaint, a parking violation, which was swiftly rectified by the Caleidos team.

“[Caleidos isn’t breaking rules] as far as I understand it, the learning pod is an allowable use under state law, and state law becomes encoded in this particular situation from the way it has been explained to me by the city attorney,” West added in the statement. “With that being said, I’ve continued to tell neighbors that if there is a code violation, we are happy to help with that code violation.”

West’s office may not have received an influx of official complaints, but according to some, this isn’t the first example of the team behind the learning pod doing less than loving their neighbors.

Jessica Patrice Turner

The Nightmare On Montclair Avenue

Caleidos, the passion project of the co-founders, Lee and Guerra, didn’t start on Alden. It used to be just a few miles away, in the backyard of Lee’s historic home on a winding hill in the affluent Kessler neighborhood, and operated under the name The Llamitas School, as evidenced by the school’s presence on the Caleidos official Instagram page. The house lies in the middle of a high-traffic and tight Montclair Avenue, which connects the estates of Dallas’ old millionaire row on Colorado Boulevard directly to the commercial Davis Street.

The high-traffic community of Kessler offers higher competition for parking than Ravinia and less peace on the hilly roads that cars race down in short-cut paths. Living in Kessler is an investment, and the homeowners closest to Stevens Park Golf Course, which is situated in the heart of the neighborhood, with a pro shop just off Montclair, want the peace they pay a high price for.

“It was really bad when [Llamitas] first started,” said Tamara Steele, the homeowner directly across the street from the old location of the school, before it was a learning pod in another neighborhood. “We didn’t know it was a school. Most of us thought it was a daycare. Parking was an issue.”

Steele says that when the school first began, around 2023, before Guerra joined the team, there were dozens of children running in the backyard, an equal number of cars dropping them off, and a permanent line of staff parked up and down the way. The children, she estimates to be about 25, spent all day, every day screaming outside, part of the natural, hands-on, holistic learning that Lee seems to so ardently believe in.

“The direct neighbor on the side and behind them probably had it the worst,” Steele said. “I could hear them in my garage with the garage door closed. If I could hear them, I would call and file a noise complaint. I would file parking complaints. … Very inconvenient, very inconsiderate of the neighbors, really. Nobody knew what was going on. It just escalated to tension.”

Steele filed at least nine complaints between September 2024 and February 2025, admitting she likely seems curmudgeonly to those who didn’t have to deal with the constant screaming.

“If it is not directly affecting you, we probably look like Karens,” she said.

However, Steele and even the women of Ravinia Heights have less of a problem with the peculiarities of the holistic curricular approach and more complaints about the courtesy of the business owners operating out of residential districts.

“Ultimately, for me, it was the lack of regard for our neighbors and the traffic, the parking, and the noise,” she said. “… While it’s weird, to each their own, I did not sign up to live across the street from school. If I would have done that, I would have paid much less to go down the street.”

While operating as a school, Llamitas was subject to parking minimums, licensing requirements and land use restrictions at the house on Montclair Avenue. According to Steele, who had contentious regular communications with Lee, the school was well aware of its unpopularity and had always planned to move.

“It affected us,” Steele said. “It affected our peace. That was what the biggest issue was. They had never been great neighbors, but when [the school] started, it just went really downhill.”

After a year of constant turmoil in Kessler, the founders learned as they went, solidifying their security under a new name and designation on Alden Avenue. According to them, they’re not nearly as bad as their neighbors say.

Caleidos Point of View

There are fair and valid criticisms of the Texas public education system. Traditional schooling may not be a good fit for many parents and their children. That’s why Lee developed her idea for an educational concept that would fill the gap for parents seeking more experimental learning systems that encourage natural growth, fostering students’ interests and passions.

“Our mission is to create a safe, nurturing environment where children can learn through nature, connection, bilingualism, and hands-on exploration,” the school said in a statement provided to the Observer. “We follow a nature-based approach because research consistently shows that time outdoors supports children’s wellbeing, emotion regulation, and curiosity.”

Caleidos did not agree to an interview, but did provide a statement regarding the tensions between the learning pod and the neighbors, maintaining that it is well within code and, if anything, are an addition to the neighborhood.

“We care deeply about being thoughtful neighbors. Since our founding, we have worked closely with Dallas City Code and city officials to ensure we remain in full compliance,” the statement said. “… Many neighbors have shared appreciation for the sense of life, care, and connection the program brings to the block.”

Caleidos also provided positive testimony from nearby neighbors; however, the existence of these neighbors could not be verified using Dallas County property records.

Unless the group of kids gets close to breaking the sound barrier or the street begins to look like a used car lot, the people who hope to see Caleidos closed or change its ways are out of luck, at least until 2027, when the next legislative session begins.

The Long Road Ahead

The women of Ravinia Heights refuse to quit, anxious about the implications of further developments and the potential for expansion if the learning pod is allowed to stay. They’ve considered applying for status as a conservation district, which would introduce much heavier regulations on business operations in the neighborhood, though the Learning Pod Protection Act may still stand in the way.

The women, on council member West’s recommendation, made contact with Rep. González, and may have to wait for state law to change before Caleidos can be regulated at all.

But González is taking the issue seriously, recognizing the flaws introduced by a vague and dated bill.

“Now that social distancing isn’t required in our schools, I strongly believe the Legislature should revisit this law to make strategic changes that increase neighborhood autonomy and ensure ‘learning pods’ have proper oversight by education experts, city officials, and partners in public safety,” she said in a statement. “This is crucial to ensure spaces meant for children are subject to fire codes, child facility codes, and that teachers have proper background checks. I am committed to finding consensus with our neighbors, and I will introduce a bill next session to address these problems.”

For now, Caleidos appears to be saved by the bill, but the women of Ravinia Heights remain hopeful that school will be out forever one day.