Illustration by Kate Jarvik Birch

Audio By Carbonatix

It took Morning Alexander 26 years to leave the cult within which she was born, and as she left, she was sure God would strike her down.

Her whole life, others had told Alexander that if she ever turned her back on the 510-acre farm where every person she’d ever known lived, she’d be raped, abused and killed. God would kill her two children in a car wreck, and their blood would be on her hands. She’d be walking herself through the gates of hell.

Alexander knew her name would be “trashed” among those who stayed behind. Leaders of the church central to their community would tell the congregation she was a prostitute or a swinger, or maybe something worse. Her decision to leave cost her her job and her home. She “sobbed” reading text messages from family members who said they’d have nothing to do with her or her children.

But it is a decision she would make again and again.

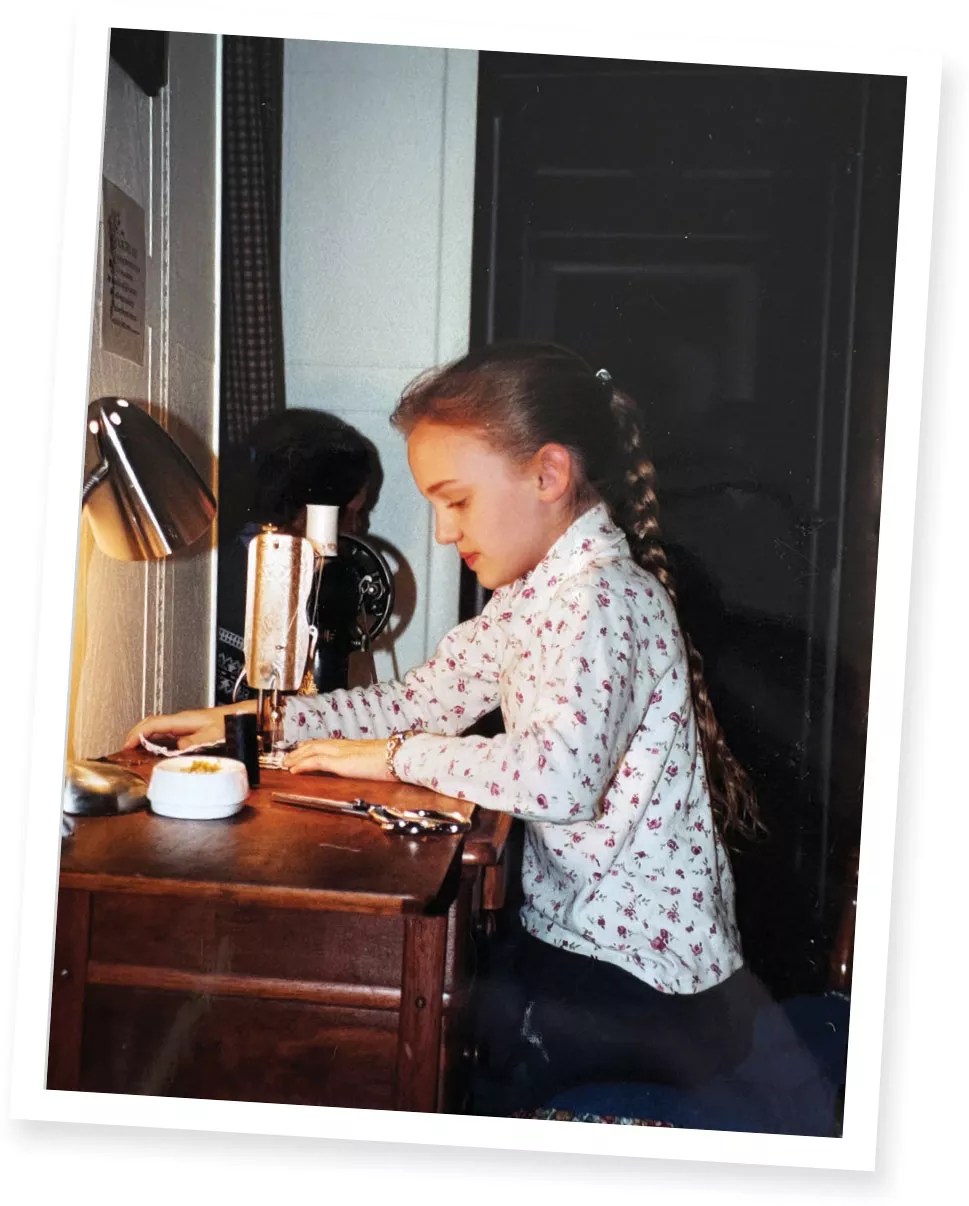

As a young child, Morning Alexander sewed potholders and other products at Homestead Heritage.

courtesy Morning Alexander

The group that Alexander was born into identifies itself online as a “Bible-believing church community” that is “dedicated to strong family values and simple living.” Homestead Heritage is located just north of Waco on a property called Brazos de Dios (Arms of God), and its artisanal cafe and craft shop village are open to the public, just down a dirt road from the “Cheese Cave,” an underground cheese-aging facility advertised on Interstate 35 billboards. In the craft village, a horseshoe of log cabin-inspired storefronts gives the illusion that one is strolling through Little House on the Prairie‘s Walnut Grove in pursuit of lavender-scented soap and hand-carved wooden kitchen utensils.

The organization claims to draw hundreds of thousands of visitors a year. On Saturdays, visitors can purchase hayrides for $4 a child or $8 for adults. The fiber arts studio offers a 15-minute tutorial on woven coaster-making for $32. After taxes, a night at the compound’s Mohawk Valley Inn costs around $200. There is a general store, a tea house and a coffee shop.

Those who live at Homestead dress modestly. Members learn how to respond to inquiries or criticisms from the public; one former Homesteader shared a 485-page booklet titled “Questions Visitors Ask” with the Observer. The booklet, which they said was circulated through the group through the ’90s and early 2000s, answers everything from “What crops do you grow?” to “What do you teach about baptism?” to “Are you a cult?”

The booklet states that Homestead does not define itself as a “cult,” a word generally used prejudicially to describe “anyone out of lockstep with the spirit of the times. “

Five former members, however, told the Observer they do believe Homestead Heritage is a cult and a “sinister” one at that. When Alexander, 33, decided to leave the group with her husband and two children, she felt she was finally breaking a cycle of abuse that had plagued her throughout her life.

“The whole time, I felt like I was never enough. I was never doing it right, but I was trying so hard because I thought that was my salvation,” Alexander said. “They build you up, build you up, build you up, and then kick your feet out from under you, and you’re back in that cycle again. And that’s how they keep you there.”

Homestead Heritage declined the Observer‘s request to respond to the claims made in this article. A partner with the San Antonio law firm Gately & Morris, P.C. responded to the Observer’s inquiry and accused “a coordinated group” of non-members of seeking publicity to “generate attention – and in some cases income – by spreading false and defamatory claims.”

“Without specifics, we cannot verify nor responsibly engage with allegations made anonymously or in bad faith,” the response said. “We are also deeply concerned by the accusatory tone and framing of your questions, and it is apparent that you are approaching this topic with a predetermined narrative and are simply seeking validation for assumptions rather than understanding or truth.”

Obey Your Leaders and Submit to Them

By the time Homestead Heritage moved to Texas, it was two decades in the making; their landing in Waco was coincidentally timed with the raid by federal agents on the Branch Davidian cult in 1993, which led to a 51-day siege and nearly 80 deaths. The Homestead website admits locals sometimes confused the church group with David Koresh’s cult, just 15 miles to Homestead’s East at Mount Carmel.

Founder Blair Adams started the Homestead congregation in 1973 in New York City, where he’d served as a missionary for the United Pentecostal Church. Around 30 members moved to New Jersey three years later. Homestead’s website says members “immediately saw the need” to implement homeschooling for children, to grow their own food and to begin giving birth at home rather than the hospital. In 1980, around 100 Homesteaders moved to Colorado while a second group began settling in Texas. A decade later, Homestead relocated its primary operations to Waco.

The group does not associate itself or its teachings with any organized branch of Christianity. Homestead Heritage’s website claims the group’s practice of basing their beliefs directly on the Bible likely makes them “more traditional than much of what has come to be called Christianity today.”

Online, the church says its membership hovers around 1,000, a quarter of whom live on the Brazos de Dios property. The remaining families live on nearby plots of land.

Hope Glueck’s family was among the first to make a home at Brazos de Dios.

Her parents were both Homesteaders when they met. Her mother, an original church member from the New York days, served as a nanny and housekeeper for the Adamses and their 10 children. (A former member told the Observer this is one of the most “prestigious” roles an unmarried woman can hope to have within the group.)

Glueck’s father was a member of the now-defunct Austin congregation. As a plumber, he prepared the Waco farm for the church’s arrival. Both of Glueck’s parents and a brother are members of Homestead Heritage.

“My parents are what I like to call true believers. My mom especially, working for the Adams family, she really idolized them,” Glueck said. “Everyone idolized Blair because that’s what he demanded.”

A charismatic leader is a key ingredient in the cultic formula, say Wendy and Doug Duncan, residents of Garland who have spent the last 17 years running a support group and counseling services for former cult members. In addition to counseling former members of Scientology, Keith Raniere’s NXIVM and the Twin Flame Universe, the couple has had several former Homestead Heritage members pass through their support group.

Based on the testimonies of those former members, the Duncans believe many of Homestead Heritage’s practices and values – the demands for confession, purity, total faith and isolation from those outside the organization – are consistent with the typical cult. Cultic groups reflect the times, the Duncans said. In the 1960s and 1970s, cult popularization reflected society’s upheaval; when the COVID-19 pandemic began, it “felt like 1968 again,” Doug Duncan said.

In the last decade, cults similar to those in the late 20th century have proliferated online, especially targeting individuals looking for romance or companionship. The ongoing “loneliness epidemic,” documented by psychologists at Harvard, poses a worrying vulnerability that charismatic leaders can exploit, the Duncans said.

“We have a yearning for community,” Doug Duncan said. “It makes people vulnerable, and unscrupulous, narcissistic leaders exploit people’s vulnerabilities. That’s how they get recruited into cults. … It does not matter how educated you are, how intelligent you are, how much money you have.”

Members who join Homestead Heritage believe their salvation rests entirely in Adams’ religious teachings; those born into the group learn of the theologian’s infallibility. A person born into a cult, known as a “second generation” member, has no pre-cult identity to rely on once in the outside world.

“The core characteristic of all cults is that they change the personality of the person who’s involved,” Doug Duncan said. “And that’s why it’s so hard for second generations because they don’t even get to know what their personality is before it’s poured into the mold.”

Each former member who spoke with the Observer is a second-generation member. They described Adams, who died in 2021, as “malevolent,” “terrifying” and a “supreme leader.” While Homestead says a plurality of elders rather than one individual governs the group, several former members said those elders served at Adams’ pleasure.

As a youth, Alexander also milked cows as part of her list of chores.

courtesy Morning Alexander

Multiple former members told the Observer the church leader had a parking spot at the church separate from the congregation’s parking lot, and he entered the church from his own entrance so that “he didn’t mingle with the people unless he actually wanted to.” Joseph Haugh, who left the group at 30 in 2018, said he knew Adams “the way that people know their favorite singer.”

Church services, called meetings, are held multiple days a week, former members said, but it was the Sunday meeting they were most weary of. Former members said the service typically started mid-afternoon and lasted hours, and Adams’ mood would dictate the message.

“I remember times where he would just come and be absolutely furious; he’d publicly humiliate four or five people by name. And in some cases, he’d excommunicate them publicly,” Haugh said. “It was a show of force.”

Homestead Heritage enforces two levels of church discipline that they believe come from Biblical teachings: disassociation and disfellowship. In a YouTube video posted to a Homestead-affiliated account, Adams’ son Asi Adams says “there is a level where someone is such a betrayer and so insolent in their rebellion against God that they are no longer considered a brother. In that case, they are outside the fellowship of the church covenant. They are disfellowshipped.” Disassociation, he adds, describes “a brother in consistent error” who remains a member of the church “while he works through his problem.”

Multiple former members told the Observer that being disfellowshiped from the group means severing all ties with the community. Former members who have maintained some communication with family members who are still a part of Homestead described the relationships as strained.

“Older teenagers and people in their 20s would leave and then be gone forever, and that was really unnerving,” said JT, who was born into Homestead and left with some family members at 17. “There was this sense that if you made the wrong move, you could be thrown out too, and that would have really serious consequences for your life. … That’s the terrifying side of the cult.”

JT, who asked to be referred to by his first and middle initial because of his career as an elected official, has a brother who is still a member of Homestead Heritage. While they had maintained the semblance of a relationship in the decades after JT left the group, it “completely disintegrated” after the suicide of JT’s 18-year-old niece. JT said he asked for accountability for the death and was cut off.

While no one will ever know what was going through his niece’s mind at the time of her death, he says he can’t ignore that she was around the age when church leaders started pressuring those born into the group to choose whether they were going to stay or leave.

Former members recall that children began attending church meetings at a young age, and the messaging was not tempered for this audience.

Yeshiah Haugh, Joseph’s older brother, recalls being only 7 or 8 when Adams began prophesizing an imminent Islamic invasion in the United States. Adams preached about a Christian woman being chainsawed into pieces by Islamic extremists for refusing to convert; the leader would stand on his pulpit and warn that terrorists were going to turn the nation’s shopping malls into reeducation camps where every American would be forced to learn the Quran, Yeshiah said

Adams’ obsession with the end times appeared in sermons during Yeshiah’s childhood; Comet Hale-Bopp in 1999 was a sign of Earth’s end, Y2k spelled doom to come and the 2008 Beijing Olympics would bring war. The theme of martyrdom ran through many teachings, Yeshiah said, and Homestead’s religious leaders made it clear to him there were no other “real Christians anyplace else in the world.”

“Brother Blair said that God told him [about the end times] so it’s going to happen, and then when it wouldn’t happen, no one cared. It was the weirdest thing,” Yeshiah said. “I mean, maybe they did [care] and just didn’t say anything. It would bug me, but I guess I didn’t say anything either. Because, you know, it’s never a good day to blow up your life.”

In All Toil There Is Profit

Former Homestead Heritage members describe a culture of financial abuse in the community. Each recounted being put to work early for little or no pay.

Glueck, who left the community in 2016 at 21 years old, started making ice cream in the group’s cafe at age 7, then transitioned to a shift a week working evenings in the grocery store. She and a small group of children spent several years portioning out bulk orders of oats and flour to be sold to members, she said. She never saw a cent for the work.

Alexander remembers hearing leaders repeat the phrase “work is worship,” and community leaders regulated the activities a child participated in. For girls, sewing or pottery was encouraged; blacksmithing was for boys. Former members shared experiences of being discouraged by church elders to pursue a passion – violin, for example – at young ages; they were instead strongly encouraged to follow the craft-learning model on which Homestead is built. Alexander feels the emphasis on learning a trade is part of the “brainwashing” and “child abuse” Homestead Heritage relies on.

“What are the things I missed out on because someone decided for me what would bring me fulfillment? I wasn’t allowed to discover that myself,” Alexander said. “You have a sense of loss. … I’m not athletic. I was never going to have a career in sports, but I wish I had had the opportunity to try.”

Craft village or fairs sold wares created by Homestead’s children, but none of the former members the Observer spoke to recall receiving compensation for their work. They said that the time dedicated to crafting is a key opportunity for socialization and is often built into the loose homeschooling curriculum all Homestead children follow. Multiple former members said the emphasis on homeschooling appealed to their parents when they joined the group.

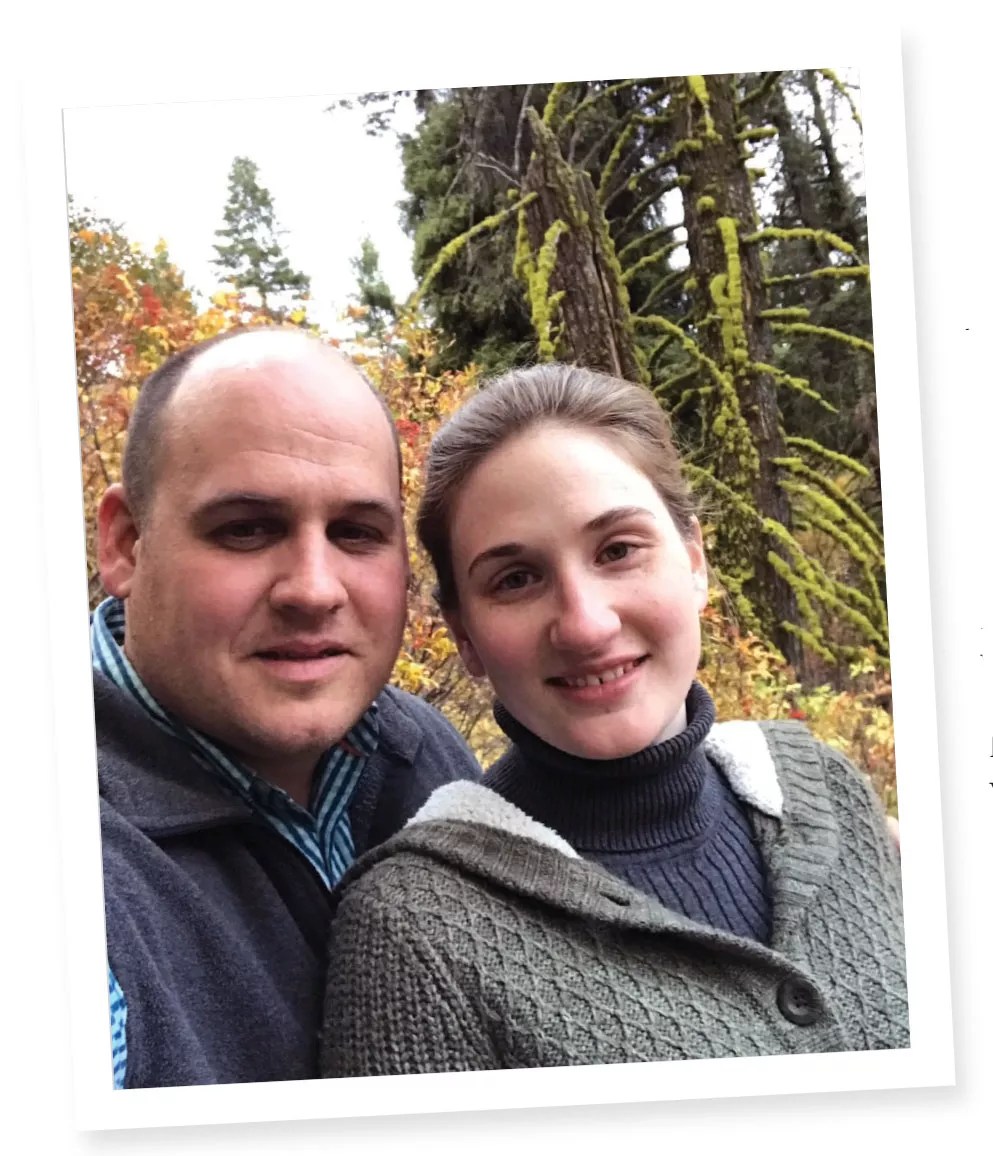

Yeshiah Haugh and his wife Noa left Homestead Heritage 10 days before their son’s first birthday.

courtesy Yeshiah Haugh

While the organization says parents are allowed to choose the curriculum that best suits their family, former members say the church is not “unopinionated” about it. Accounts of former members’ homeschooling education vary, but all said science subjects were not on the curriculum. History lessons typically revolved around stories of persecution, such as the Holocaust.

“One of the phrases I remember was that they were educating their children for an alternative reality,” JT said. “There was a sense that we weren’t really being educated to do well in the world. We were being educated to do well in the community. And what was needed in the community wasn’t necessarily what was needed anywhere else.”

Most families lived off a single income, so mothers could stay at home to raise the children and lead homeschooling.

Adults are required to put at least 10% of their earnings back into the church, former members said. There is no community pot for basic needs, and Yeshiah said the low wages offered by Homestead jobs were often insufficient to cover bills, leading young families to take on debt.

For the most part, Homesteaders work for Homestead’s many entrepreneurial endeavors, often for minimum wage. While the community says young adults are permitted to leave the group to attend college or a trade school, former members said that is uncommon.

“There have been people who are literally called out by name in church services until they were bawling for wanting to go to nursing school,” Joseph said.

A Gracious Woman Gets Honor

Things within Homestead Heritage first “blew up” for Alexander around the time she turned 14. When she was caught lying for her older brother, several church elders, men older than her father, called her into a meeting where she was “pounded her with questions” until she “broke.”

“They were screaming at me. They were asking me leading questions of sexual nature. They were just inappropriate, and I was completely panicked. So I was like, OK, I’ll confess. I told them I had listened to secular radio,” she said. “And they lost their shit.”

The elders told Alexander’s family she had a “dark spirit.” For several months, she was “grounded” from church activities-her only form of socialization-and the only community members she was permitted to speak with were her parents and a neighbor who made brooms for the community. So, she spent the next few months making brooms “just so she had someone to talk to.”

Looking back, Alexander said she feels she would have been in trouble no matter how she’d handled the barrage of questioning because of her gender and her insubordination.

Former Homesteaders describe a community deeply bound by traditional gender roles. While men work and hold leadership positions within the church, the group expects married women to rear children and lead homeschooling while remaining subservient to their husbands. Modesty standards imposed on young women have left both Alexander and Glueck working through trauma well into adulthood.

Young women were watched like “zoo animals,” Alexander said: If you wore red, you were admonished for wearing the color of prostitutes. If a floral pattern was too vibrant, you were criticized for calling attention to yourself.

Glueck, who hails from a line of “stocky” German ancestors, said she was 9 the first time her mother put her on a diet. She remembers growing up insecure and weight-conscious, feelings that became worse as her body developed during her teenage years. Now 30, she attributes her chronic back pain to the way she taught herself to walk without swaying her hips.

While thinness was prized, working out, especially in athletic wear, was deemed immodest by Homestead, Glueck said. In her late teens, she snuck out of her house at 3 a.m. to meet with a friend to watch workout videos on YouTube and take jogs through the woods.

“I went to [a friend’s] wedding, and I’d lost probably 50, 60 pounds at the time. I wore this sleeveless dress, and it was all the way down to my ankles, fully modest, and I wore a shrug sweater over top of it,” Glueck said. “I had six men call my dad that night and say my clothing was inappropriate, that I was being flirtatious.”

She was 21.

Glueck had already considered leaving the group; earlier that year, her attempt to get baptized, a decision required by the church for adults to receive full membership status, had been denied over an incident at her family’s bakery, which she ran. The issue was a simple one, she said: She’d told an employee who wasn’t doing his job to start. Although she was the man’s supervisor, his status as a married man made the correction improper, leaders told her.

“I had to go pray until I told them what they wanted to hear, which was that I was out of my place as a woman to speak to a man like that. And then I had to call him and apologize to him,” Glueck said. “They just want to see how high you’ll jump when they say jump. How far can they break you down, and how closely will you follow the rules?”

After her baptism was denied, Glueck began stashing money from her bakery job and making plans to leave the group. The vitriol inspired by her ankle-length dress was the “final nail in the coffin.”

Gender disparity and “desperation” also plague the Homestead marriage market, former Homesteaders said.

Community members are required to be baptized before seeking marriage, and a young man deemed ready for marriage by church leadership would be instructed to “pray” about who his wife should be; in many cases, former members claimed, the leaders already have pairings in mind, and it is the man’s job to present the correct woman’s name as the one God told him to marry.

After the man confirms the pairing, women are told to “pray” in the same manner, and while they theoretically could decline an arrangement, Yeshiah said the community has more women than men.

“It was always the guy responsible for essentially picking the female,” Yeshiah said. “If [a woman] had something come along that was an opportunity, and she didn’t take it, that might be the last train to the coast. There was no guarantee something better was going to come along.”

Unmarried people were treated as “second-class citizens” throughout the community, he added, contributing to the sense of urgency that surrounded marriage.

Alexander realized she’d become engaged, married, pregnant and then with a newborn all within a year.

courtesy Morning Alexander

Alexander was told by church leaders to begin praying for a husband at 18; two years later, in 2012, she received a call at work instructing her to go home and prepare for a proposal. She notified her parents, who were no longer group members and accepted the proposal of a man with whom she had never had a one-on-one conversation.

“It’s not like I’m marrying him because I love him and I know him. I’m marrying him because God told me to,” Alexander said. “Life moves so fast, and you don’t have time to get to know each other. … You’re living with someone you’ve never dated; it’s unbelievable. It really is just nuts.”

Twelve weeks later she was married and became pregnant eight weeks later. When her eldest son was born two months prematurely, she realized she’d become engaged, married, and a mother in less than a year. At that time, she was happy to “submit as a wife” because it’s what she’d always been taught.

When Alexander left Homestead Heritage in 2018, her husband joined her. Seven years later, they are “respectfully and amicably” in the process of getting a divorce.

“We just kind of came to the realization that we were two very different people that weren’t necessarily compatible and hadn’t been for a very long time and probably weren’t going to be. Which feels like a very normal conclusion,” Alexander said. “We didn’t have the chance to find that out. We were set up to fail from the start.”

Blows That Wound Cleanse Away Evil

l Several former Homestead Heritage members told the Observer that an “increasing level of cognitive dissonance” defined the years before they left the community. Wendy and Doug Duncan said this is a normal occurrence among cult members.

“When you are in that position, you actually are dissociated from a part of yourself, which is exactly what trauma does,” Wendy Duncan said.

Many cults teach members not to trust themselves and to “wall off any piece” of their consciousness that may object to or question the community surrounding them, she said. Several former Homestead members said that was what they learned.

For Joseph, that feeling of dissociation was especially true. In the early 2010s, he was part of a group of church members charged with responding to a series of reports released by WFAA and the Texas Observer that accused the group of failing to report child sex abuse. To help form the group’s response, Joseph Haugh was responsible for researching how other cults handled similar accusations.

Even while researching cults, it was difficult for him to define Homestead as such, he said, because “Homestead is extremely good at making negative statements about them feel like an attack.” The negative press triggered all of the warnings of martyrdom and persecution that had been instilled in him throughout his childhood.

“I probably would not have left without understanding Scientology. … I view them as a mostly pointless organization, but it was really important because they don’t subscribe to a particular God,” Joseph said. “All those things that [the church said] were attacks on our religious beliefs, Scientology was being attacked for the same thing, and it wasn’t a religious attack.”

While a person can escape a cult for any number of reasons, the Duncans said the shift in perspective offered by parenthood can be the reason a person who is questioning their group’s legitimacy decides to leave. That was the case for Yeshiah, who had spent the first decade of his adulthood “indescribably lonely,” trying to persuade the church to let him take a wife. He married his wife in 2016, and his eldest son was born a year later.

The night Yeshiah went into the nursery, his son was only a few weeks old. He didn’t turn on the light because he didn’t want to wake up the newborn; in the dark, he picked up his son, sat in the nursery rocking chair and was “overwhelmed” with emotions. Silent tears ran down his face when he decided that “he would not teach [his son] how to survive in that environment.”

“I knew in my heart and my soul that I could not do to my son what had been done to me,” Yeshiah said. “I told my wife about the experience, and she started crying. She said she’d had the exact same thing happen. … We left 10 days before his first birthday. He has no memory of the entire thing.”

Twice a year, Homestead members must sign a book called “Confessions for Baptism and Communion,” which recommits them to the church. Yeshiah and his wife had been tossing around the idea of leaving for several months, and when the time came to sign the book again, he told his church leader they “would never sign” it “as long as we lived.”

That night, the group disfellowshipped them. As Yeshiah remembers it, they were told they were “crucifying Jesus a second time,” that they were guilty of his death and that they would never find a real Christian again. They were told they’d never feel God’s presence “as long as they lived,” he said.

Yeshiah and his wife packed what little they owned into a small U-Haul. Saddled with debt and feeling like their hearts were being “ripped out,” they drove away from Homestead Heritage.

Like several other former members the Observer spoke with, Yeshiah and his wife began attending Antioch Church in Waco after leaving Homestead. The nondenominational church can be “intense,” Alexander said, making it a familiar place to land.

With no money to their name, Yeshiah’s family spent their first month in Waco trying not to end up under a bridge. Antioch was a chance to decompress in a familiar setting and begin building a new community. It was just before Christmas, and toward the end of the service, the congregation began passing around candles.

The lights dimmed. Candles bathed the church in a warm, flickering glow. Softly, slowly, the churchgoers sang the hymn “O’ Holy Night.” Although Homestead recognizes the birth of Jesus as a holiday, Santa, elves, stockings and trees are not part of the celebration. Yeshiah had never seen anything like that Christmas service before.

He can recite the song’s third verse to this day:

Chains shall He break, for the slave is our brother;

And in His name, all oppression shall cease.

Surrounded by strangers and haunted by the song, Yeshiah was certain that the tight feeling in his chest had something to do with God. Years later, he still gets choked up when he remembers the experience.

“That feeling, that emotion that they said we’d never feel again, was so thick in the place,” he said. “There was so much pain for the fact that so many of our family and friends were chained slaves 10 miles down the road. And we had no access to them. We could not talk to them. We couldn’t explain this.”

For Alexander, leaving Homestead Heritage meant learning simple social cues. She was 26 when she learned how to order from a bar and what a hangover is. She had to Google what to wear to her local community college classes and how a job interview works. She didn’t know how to enroll her children in school. She remembers standing in a store “cluelessly” holding a stack of jeans because she didn’t know her size. She had never worn jeans before.

Seven years after leaving, she sees Homestead Heritage everywhere. When the movie musical Wicked came out late last year, she saw it multiple times in theaters and “sobbed” every time.

“It all just boils down to a weak, powerless man,” she said. “You realize the emperor has no clothes, and you realize he’s never had any clothes.”

Former members describe feeling emotionally, socially and educationally stunted when navigating the post-Homestead world. Many have turned away from organized religion altogether.

In addition to everything included in this article, former members of Homestead Heritage detailed witnessing or being victims of extreme corporal punishment and medical malpractice during home births. Once defining itself as apolitical, the group, under the leadership of Blair Adams’ son Asi since the founder’s death, has begun espousing politically conservative messaging, former members added.

“I don’t think that Homestead would fall into Christianity. I truly believe that they mostly worship Homestead. Homestead is their god,” Joseph said. “My experience tells me that Homestead could get the people there to violate absolutely any moral or biblical standard.”

According to the Homestead Heritage website, the group sponsors communities in five U.S. states and 10 countries on five continents. There are eight Homestead Heritage families in India, 10 in South Africa, seven in New Zealand and 25 in Wisconsin.

The group’s website reads: “We are committed to restoring the church as a community and culture for a wholesome and harmonious life.”

A FAQ section adds, “Anyone can join.”