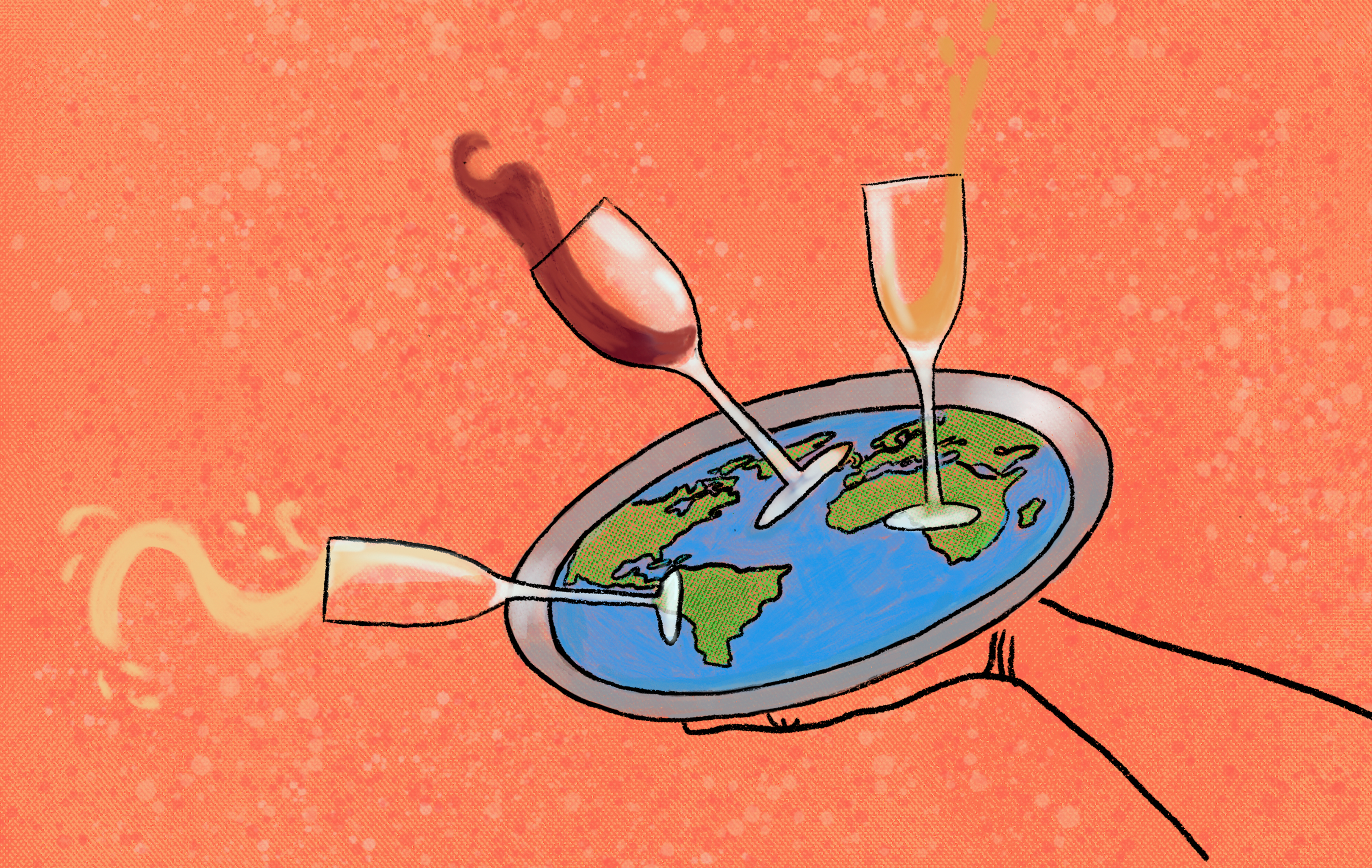

Illustration by Sarah Schumacher

Audio By Carbonatix

Recently, I called a Dallas-area bar owner to discuss drinking trends leading into 2025. I was looking for something like an increase in a certain kind of liquor or cocktail: mezcal or carajillo, perhaps. Is vegan fat washing actually a thing (it is), and is gin really making a comeback (also true)? What about the sober movement?

But instead of any of those things, the longtime barkeep, who wants to remain anonymous given the divisive political climate, is worried about something completely different: tariffs and how they’ll increase the cost of a night out in Dallas.

“We’ve seen this movie before,” they said, referring to tariffs imposed during the first Donald Trump administration. There are two big ones that impacted liquor sales: In 2019, Trump slapped a 25% tariff on French, Spanish, German and UK wines in retaliation for a deal the European Union made with aircraft manufacturer Airbus. The “Airbus tax,” as it was called, caused French wine exports to drop by 14% at the time, triggering a ripple effect of increased prices.

And a year prior to that, Trump imposed a 10% tariff on all aluminum imports and 25% on steel products, leading the European Union to slap a retaliatory tariff on American whiskeys (likely a jab at then-Senate Majority Leader Mitch McConnell’s home state of Kentucky, the center of the bourbon industry).

The Distilled Spirits Council estimates that from 2018 to 2022, when Biden lifted the tariffs, American whiskey exports to the EU fell by 20%, at a loss of more than $110 million for U.S. distillers. Some smaller distilleries never recovered as other countries and sellers swooped in to fill the void.

In 2020, Trump also threatened up to a 100% tax on all French sparkling wine over France’s “tech tax” levied on American companies (which is still a thing).

Then, on Monday, Nov. 25, Trump promised via social media that on his first day in office, he’ll impose a 25% tariff on all goods from Mexico and Canada, and 10% on China. Your margarita will certainly cost more.

At a campaign rally in August, Trump pledged, “We’re going to have 10-to-20% tariffs on foreign countries that have been ripping us off for years.”

Lauren Drewes Daniels

The Tipping Point

While on the campaign trail, Trump told Bloomberg News the most beautiful word in the dictionary is “tariff.” This fixation doesn’t apply only to wine or whiskey; these are merely two examples from his previous administration that impacted American businesses.

At a campaign rally in August, Trump pledged, “We’re going to have 10-to-20% tariffs on foreign countries that have been ripping us off for years.”

Brooks Anderson has made a career in the wine business in Dallas as the founder of Veritas Wine Room and the restaurants Boulevardier and Rapscallion.

“First, we have to dispel the ridiculous notion that the foreign producer or foreign government pays the tariffs,” Anderson says. “American businesses and American consumers will pay the tariffs. That’s ECON 101.”

The tariffs will roll downhill, and the costs will be passed to the consumers, bar, restaurant, or wine shop, Anderson says.

Ben Aneff is the president of the Wine Trade Alliance and managing partner of Tribeca Wine Merchants in New York. He understands tariffs are intended to hurt foreign companies but points out that the vast majority of the revenue from imported wine in the U.S. stays with small businesses in the U.S.

“The biggest profit percentages are from restaurants,” Aneff says. “But it’s not a luxury that they make profits on their beverage program. It’s the only way they stay in business.”

Add to that, the economy is a different beast now than it was in 2019, and absorbing higher-priced wines, which distributors were able to do then, might not be possible now with already increased food prices. Doug Shaw, the president of M.S. Walker, a wine and spirits importer and distributor, told the beverage business news outlet SevenFifty Daily that the high cost of business now, namely inflation, will shift the tax burden to customers.

TouchBistro, an all-in-one, point-of-sale-and-management system for restaurants, surveyed 600 full-service U.S. restaurants in major cities, including Dallas. Restaurants reported spending 34% more on food this year compared to last year. And even though people are eating out more often this year compared to last, according to OpenTable, these increased costs, along with labor costs, eat into profits. Nearly every operator (99%) told TouchBistro they’ve spent more on labor this year compared to last, but they also reported that “despite the financial strain, reducing headcount was the least common strategy used to reduce labor costs.”

Dino Santonicola, chef and owner of the local Italian restaurant Partenope, has an almost hands-in-the-air response to the question of higher tariffs.

“Honestly, everything has been increasing in the last 4 years,” Santonicola says. “Our labor today is 25% more than it used to be, so I guess we will adapt like we have been doing.”

Another long-time Dallas operator with more than three decades of experience in both the small restaurant business and retail, who also wants to remain anonymous because of tensions surrounding politics, says a 20% tariff would absolutely crush the already slim margins in the restaurant business.

“There really is no room for higher costs – food or booze – and many places can’t afford to raise prices because customers will simply opt-out,” they said.

There’s also a shift in alcohol consumption over the last few years, which makes it harder for restaurants to make a profit, they add. People are drinking less and spending less on what they buy. Tariffs would exacerbate that trend.

Swap One Sip for the Other

If tariffs are placed on foreign wines, won’t restaurants and drinkers just buy more American wine, meaning more money for American businesses? Aneff says it’s not that simple. The liquor industry is propped up by a three-tiered system that includes importers and distributors who rely on large volumes to transport bottles across the country. If a part of that network dries up, the economies of scale are knocked off kilter, raising prices.

“They [foreign wineries] have to sell their wine to a U.S.-owned importer,” Aneff says, “And that U.S.-owned importer sells it to a U.S.-owned distribution company, and that U.S.-owned distribution company sells it to restaurants and retailers. Almost all of that chain is made up of American businesses.”

Umit Gurun, a professor at the Jindal School of Management at UT Dallas, says high-end restaurants and bars where clients aren’t so price-sensitive might not have a hard time with a 5% increase in a glass of wine.

Given what we saw when tariffs were placed on booze in the previous Trump administration, is it a fair expectation that a night out will cost more? Gurun says yes, pointing out that it depends on multiple factors, including how high the tariffs are and whether the businesses can absorb the costs or will be forced to pass them along to consumers. The long-term impact, he says, will be predicated on how long trade tensions and tariffs remain in place

“It’ll be interesting,” Gurun says. “The next couple of years we will see. There’s some expectation that, based on the past, we’re going to see similar sort of effects on all aspects of economic life.”

The Atlantic took a deep dive into more of those economic aspects of tariffs and how mass deportations could affect food prices.

“The immigration and tariff policies, in other words, would affect all the food we eat: snacks, school lunches, lattes, pet food, fast food, fancy restaurant dinners,” writes The Atlantic journalist Ellen Cushing. “People will not stop eating if food gets more expensive; they will just spend more of their money on it.”

Cushing asked Rachel Friedberg, an economics lecturer at Brown University, if there were any scenario under which the new administration’s policies don’t force prices up: “No,” she said, without pausing. “I am extremely confident that food will get more expensive. Buy those frozen vegetables now.”

Might want to pick up a few bottles of your favorite Bordeaux as well.