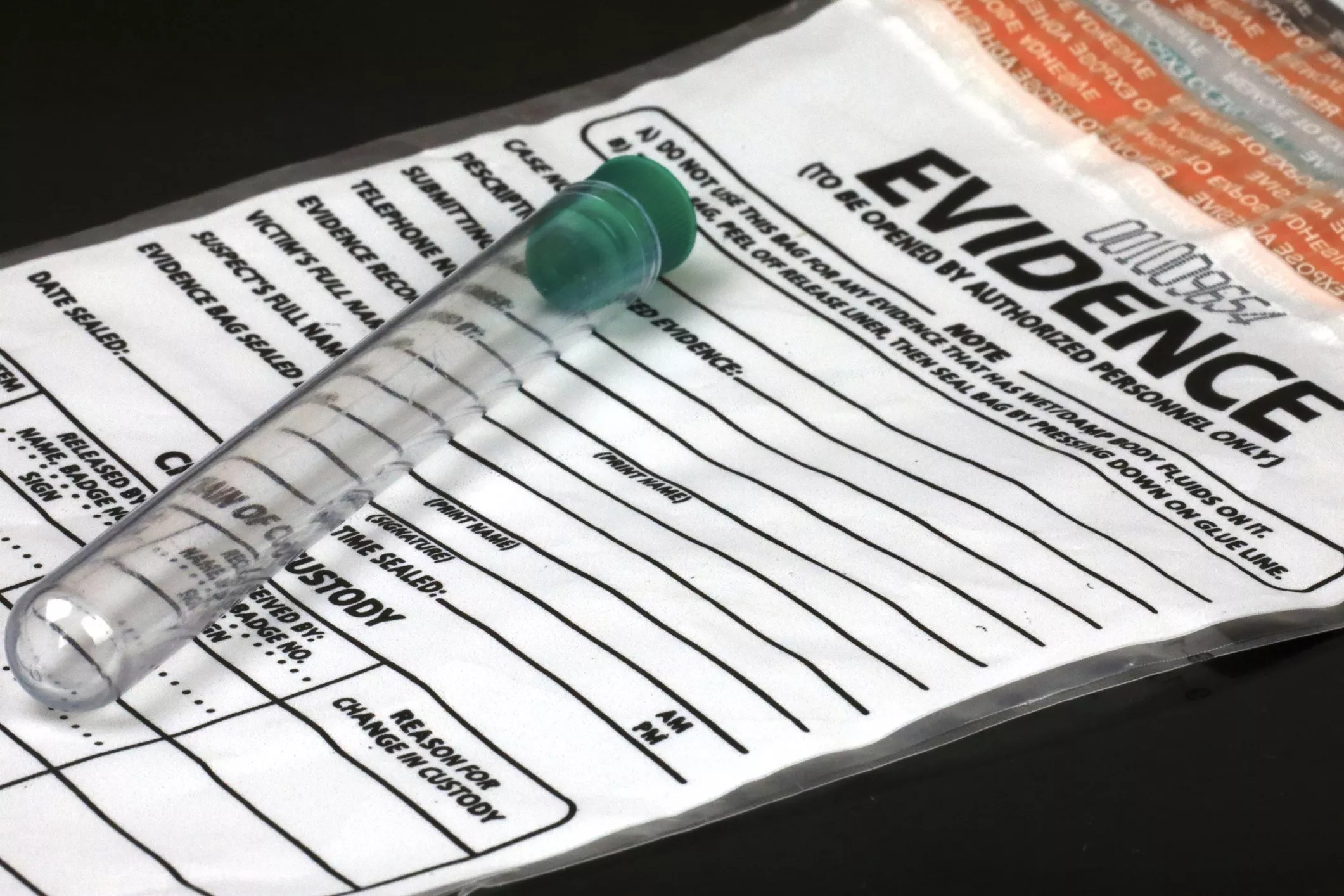

Douglas Sacha/Getty Images

Audio By Carbonatix

The Fort Worth Police Department is sitting on hundreds of untested sexual assault evidence kits despite a 2019 law mandating evidence be sent to a lab and processed within a 120-day window, a recent NBC5 investigation found, leaving victims right’s advocates concerned that Texas police departments are failing survivors of sexually violent crimes.

According to the NBC5 investigation, Fort Worth police failed to send DNA evidence kits to a lab within the state-mandated 30-day deadline 43% of the time over the last five years, submitting hundreds of kits more than 100 days late, and 28 kits over a year late. In the lab, 901 kits have waited 90 days or more to be tested, missing the state deadline given for DNA processing.

The number makes up the majority of the state’s 1,130 untested rape kits, although victim’s advocate attorney Michelle Simpson Tuegel is hesitant to label Fort Worth’s backlog an isolated incident. The dismal numbers leave her concerned about the reality victims across Texas face when trying to get justice.

“I’ve read all [of the Fort Worth Police Department’s] excuses as to why, they claim, they can’t [test the kits on time], but it seems like survivors are caught in bureaucracy, and that just has to be solved,” Tuegel told the Observer. “There’s not a good excuse for it, it impacts people’s lives.”

NBC5 spoke with a Fort Worth woman, Latrice Godfrey, whose sexual assault evidence was not processed for 11 months after she was raped in a parking lot by an acquaintance who had offered her a ride home. Godfrey was able to keep tabs on her kit’s status through the state’s online “Track Kit” portal.

“It takes so much to come forward. It takes so much to go through that exam for it to be mishandled and just to be sitting on a shelf like, ‘We get to it when we get to it,’ when my healing journey is relying on that,” Godfrey said.

Fort Worth Public Information Officer Leah Wagner told NBC5 that the department is unable to test the volume of rape kits they receive because of the department’s ongoing difficulties with hiring forensic scientists. Three of the department’s eight forensic testing positions are filled, and only one scientist is fully qualified to run tests on their own, Wagner said. Two others are in training, a process that can take two years.

Because the department runs its own lab, it has also had trouble finding private labs willing to accept kits, contributing to the backlog, she added.

But Texas police departments have had to work through overwhelming backlogs of rape kits before. In 2011, 18,000 kits sat untested on Texas law enforcement shelves. That number was brought down to 3,000 by 2019, when the Lavinia Masters Act was passed by the Texas Legislature. The act mandates the 120-day testing window given to law enforcement, and freed up millions of dollars in funding intended to be used for staffing and testing equipment.

In an interview with NBC5, state Rep. Victoria Neave Criado, who represents Dallas, confirmed “the funding is there” for departments struggling to work through backlogs. The fact that Fort Worth is not meeting deadlines, despite the available funding and state support, is indicative of the “particularly bad” conditions survivors go through while their case works through the justice system, Tuegel said.

“I try to prepare survivors that I represent for a process that’s not going to be fast, either in the criminal or civil system. But in the areas where evidence being tested is the hold up, that’s a really sad thing that we can try to fix,” Tuegel said. “We can’t always fix things like the trial docket, that’s more complicated than just testing a piece of evidence. This is a piece that they can start to remedy.”

In the days since NBC5 released their investigation, some Fort Worth leaders have promised action. Fort Worth Mayor Pro Tem Gyna M. Bivens told the station that the city is increasing hiring salaries for DNA analysts to help fill the empty seats in the department’s lab, a move that leaves her “optimistic.”

In 2022, Neave Criado told the Observer that departments could potentially lose grant funding if they failed to comply with the Lavinia Masters Act, a promise Tuegel hopes the state follows up on.

“​​Our governor said that they were going to prioritize scooping [rapists] off the streets. Well, if that’s really the case, then why isn’t the state of Texas even processing the evidence and doing so in a way that the law requires?” Tuegel asked, referencing Texas Gov. Greg Abbott’s pledge to “eliminate all rapists” from the state as justification for not including a rape exception in the state’s abortion ban. “My question for the state of Texas, who claims to really value people’s lives, is why aren’t you putting that as a priority and starting to have some teeth in enforcing the law that people like Lavinia Masters fought to pass?”