AP Photo/Pat Sullivan

Audio By Carbonatix

A few years ago, a woman, her husband and their grandson were stopped by police outside of San Antonio. It was the middle of the night, and the reason for the stop, according to the two officers, was safety: The family was approaching a high crime area. To the married couple taking their grandchild to SeaWorld, that reasoning felt flimsy.

The woman could sense something was off about the stop. After a minute, she says, she turned to the officer standing at her window. “How many untested rape kits do you have here?” she asked him.

The officer was clearly taken aback. So, the woman elaborated.

“Well, I’m Lavinia Masters,” she said, “and I ain’t all that and a bag of chips, but I fight for survivors of sexual assault. Have you heard of the Lavinia Masters Act?”

“No, ma’am,” the officer replied.

“Do you process rape kits?”

“I don’t know how that works.”

The way Masters recalls the encounter, the stumped officer returned to his car with his partner in tow to Google the name of the inquisitive woman they had just pulled over. Then they let the trio drive off with a warning to be careful.

“He was clueless,” she says of the officer, but she doesn’t blame him. His lack of awareness was part of a larger problem that still pervades Texas more than three years after the 2019 passage of the Texas law commonly known as the Lavinia Masters Act.

“‘How many other counties are thinking this way?'” Masters asked herself. “‘How many more don’t know?'”

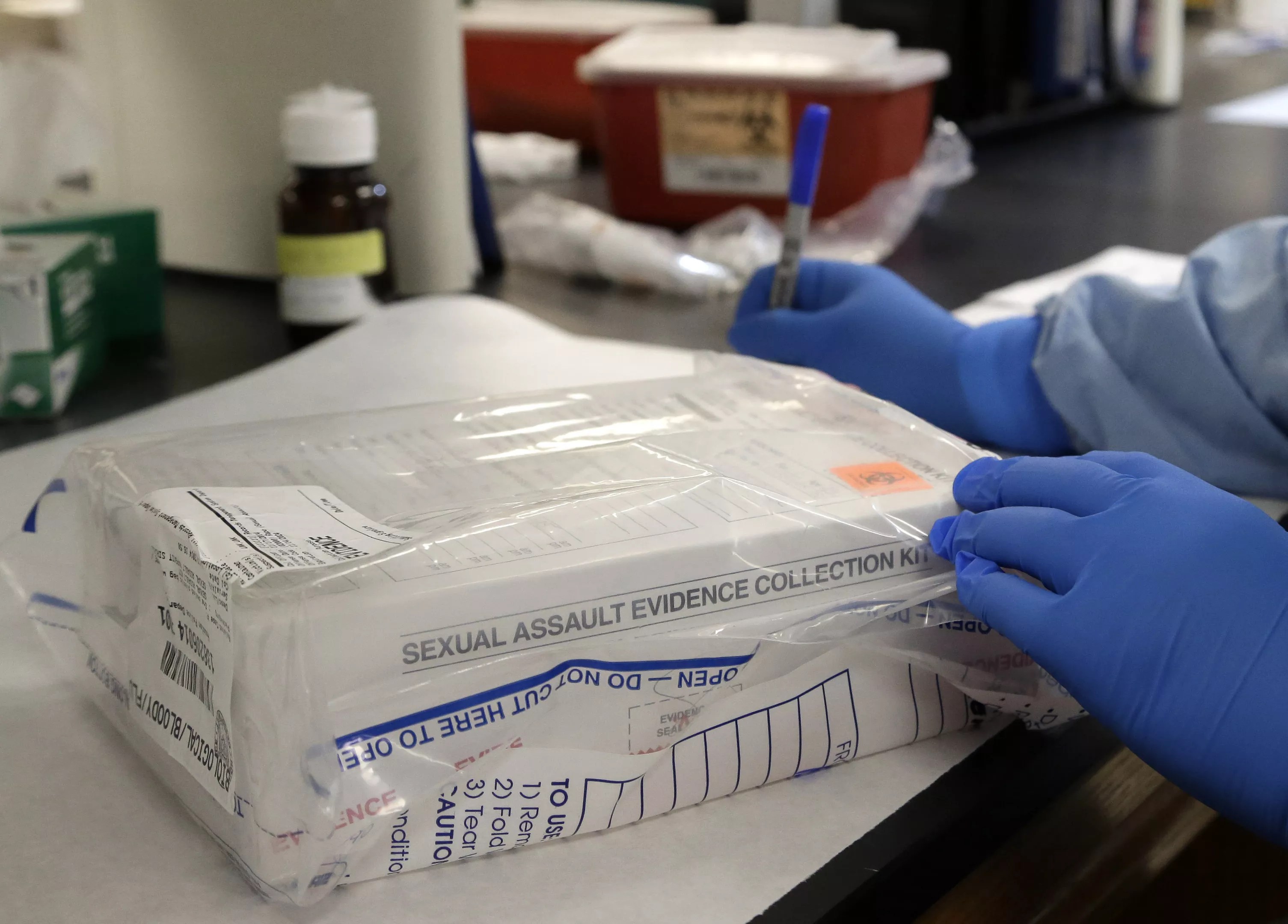

A rape kit (also known in Texas as a sexual assault kit or “SAK”) is a package of evidence collected after a rape occurs, and it typically contains shreds of DNA in the form of skin cells, semen, blood or saliva. Ideally, these kits are used to catch and jail perpetrators. But as is the case in Texas, they sometimes sit on a shelf, unprocessed for years.

Three years since that traffic stop outside San Antonio, thousands of rape kits remain untested in Texas. Since 231 law enforcement agencies did not respond to a recent statewide audit, the true number of kits is impossible to tell. Even still, the Texas Department of Public Safety (DPS) says there are currently 3,510 kits being tested across the state. That list does not include two separate backlogs in Dallas County, which is not part of the DPS system. The first Dallas backlog includes 1,000 kits collected from 1996 through 2011, while the second, which includes around 900 kits, ranges from 2011 to 2019.

Meanwhile, many states, including Florida, have cleared their backlogs entirely without implementing the same level of rape kit reform as Texas.

“One kit on the shelf is too many,” Masters says. “That’s somebody’s life hanging in the balance. That’s a rapist on the streets who is free and thinking they can violate someone else.”

Lavinia Masters gave her name and energy to a bill from the Texas Legislature in 2019 meant to eliminate the backlog of untested rape kits in the state. The backlog remains, and Masters is still fighting.

Mike Brooks

**

In 2011, a statewide backlog of more than 18,000 untested rape kits gained national headlines and prompted action from lawmakers like former Sen. Wendy Davis. Davis’ work helped significantly decrease that backlog (by 2019, for instance, the DPS backlog had about 3,000 untested rape kits) but the number of rapes far outpaced the speed at which labs could process new and existing kits.

The Lavinia Masters Act was passed to solve this problem.

Among other things, the law, which went into effect in September 2019, requires labs to process a kit within 90 days of receipt. The bill came with a $50 million investment from the state, with the bulk of that money intended for more staff and equipment. Further, as Masters puts it, the bill “stops the clock.” Now the countdown to the end of the statute of limitations for a rape charge doesn’t even begin until the kit is tested. This provision was especially important to Masters, who, in 1985, was raped by knifepoint in her Dallas home. She was 13 years old, and her rape kit sat on a shelf for 20 years.

“I didn’t just deal with the rape kit backlog,” she says. “The two cops that came out, they asked me three questions that still burn my soul. It’s like they’re etched in me: ‘Are you sure it wasn’t your boyfriend?’ ‘Are you sure you didn’t let them in the window?’ ‘Are you sure you’re not having sex and don’t want your mother to know?'”

The questions led her to disdain law enforcement for decades.

“At first I didn’t realize the hate I had for police officers growing up,” she says. “But in my world of advocacy, I realized we have to train them to be trauma-informed and survivor-centered.”

In other words, officers must be trained to respond and care for victims. Otherwise, in Masters’ opinion, they must “step out of the way.” Masters has spent years advocating for trauma-informed training, and there’s evidence that the law named after her has helped the state make significant progress.

For instance, labs run by DPS reduced their number of untested kits by over 1,000 between the end of 2020 and the end of June 2022. Additionally, Dallas County has tested nearly 4,000 kits since 2019, a number that further shames the lack of progress the city made for survivors like Masters early in the 2000s. That said, private labs are still in high demand as counties and cities, which pay for the kits, look for more resources, and many counties are simply violating the law.

“My perception is women weren’t a priority. We learned some law enforcement would hang on to the kits and not submit them for testing.” – state Rep. Victoria Neave

Masters and the bill’s author, Rep. Victoria Neave, acknowledge their work is far from finished.

“There’s still a lot of work to do in ensuring counties know their legal obligations,” Neave tells the Observer.

In the wake of the recent Dobbs ruling from the U.S. Supreme Court, which decreed that the Constitution does not provide a right to an abortion, the state’s persistent backlog has once again garnered headlines. Yet even before the Supreme Court’s ruling, Texas’ own restrictive abortion bill – and Gov. Greg Abbot’s remarks that Texas will work to “eliminate all rapists” – drew attention to the state’s backlog challenges.

“This law undermines so much of what we achieved,” Masters told The Daily Beast in 2021 after Abbott signed Senate Bill 8, which bans nearly all abortions as early as six weeks in a pregnancy. The law, which does not allow exceptions for rape, sexual abuse, incest or fetal anomaly, incensed Masters, who is a member of the Governor’s Sexual Assault Survivors’ Task Force.

“We already feel like we’re rendered powerless by the sexual assault,” she added in the 2021 interview. “And now here you come, taking more power, taking our options away.”

Nearly a year later, on the phone with the Observer, Masters was still perturbed by the governor’s comments. Her laugh belies decades of pent-up anger, which often comes out when faced with red tape and incompetence.

“I know our governor is saying we’re gonna eliminate rapists, but I was hoping he was misquoted, because that’s impossible,” she says. “We have no way of dealing with the evil that dwells in men or women.”

Masters is far from alone in her anger at the government.

In a late June story for The New Republic, journalist Katie Herchenroeder noted, “It’s not just abortion clinics that will be affected by the Dobbs decision. In particular, advocates told me, it will hurt rape crisis centers, which provide emergency contraception, forensic exams, counseling, and sexual education – while also advocating for justice for survivors, including ending the immense backlog of rape kits across the country.”

**

The experts, investigators and lawmakers interviewed for this story reveal there are a few key reasons Texas still has a backlog of untested rape kits. One is the lack of education and awareness showcased by the dead-of-night traffic stop Masters endured near San Antonio. Another major reason speaks to why Texas had such a large backlog in the first place: apathy.

“My perception is women weren’t a priority,” Neave says. “We learned some law enforcement would hang on to the kits and not submit them for testing.”

To Masters, “it’s obvious” agencies simply weren’t trying hard enough until survivors and lawmakers like Neave and Wendy Davis started making noise.

“At least we’re trying now, because it’s obvious you weren’t in the beginning, and I was very upset about that, because we were forgotten,” Masters says. “If they processed 100 kits a year, it seemed [to them] like they were making progress, and that’s unacceptable.”

Another issue is money. In the early days of her advocacy, lack of funds was a common refrain Masters heard from practically every county official she engaged. Amy Derrick, an administrative chief in the Dallas County District Attorney’s Office, echoes Masters.

“Everyone will tell you they need more money,” Derrick says. The Lavinia Masters Act has helped Dallas County keep up with the rate of new kits, but even with the $50 million invested by the state in 2019, labs run by law enforcement still don’t have the manpower they need.

“The labs need more people and more equipment, and they also need more people to choose this career path,” she says.

Soon, both of Dallas County’s rape kit backlogs will be sent to private labs. Derrick says there are even a significant number of rape kits that could qualify for a lab like Othram, which uses an advanced genealogy process known as forensic-grade genome sequencing to build a profile of a suspect, search for relatives, then nab criminals and solve decades-old cold cases. Othram used that technique to help Dallas police last month arrest a suspect in the 1989 murder of Oak Cliff resident Mary Hague Kelly. Yet an interview with Othram officials indicates the Texas government has thus far been largely uninterested in investing in their technology; one company rep said Sen. John Cornyn’s office is “one of the only offices left on the Hill who hasn’t opened their door to us for a conversation, even for 10 minutes.”

“Cornyn is known for supporting DNA technology, and unfortunately, he is one of the senators we have not been able to get on the phone with,” says Kristen Mittelman, Othram’s chief business development officer. (Cornyn wrote a 2021 op-ed decrying the state’s rape kit backlog). “He is still writing bills only supporting legacy technology,” Mittelman says. “That’s extremely disheartening, and I don’t understand where the disconnect is there. We are building the road, the pathways to clear all these backlogs, to not live in a world where people wait decades and decades to find what happened to their loved ones. What’s necessary is government buy-in.” Cornyn’s office did not respond to the Observer‘s request for comment.

In some dispiriting ways, the issues of finance and apathy are conflated. Take, for instance, a small county Masters once visited (she declined to provide its name.) She was invited to speak to a local crisis center in the county, and before her speech, a police lieutenant took the podium.

“For whatever reason, he felt compelled to talk about the kits,” Masters says. “My blood pressure rose, and I was ready to jump across the table, because he said they have kits from the ’70s and ’80s, but they weren’t going to ‘waste their money’ on processing, because ‘those people are probably dead.'”

This was 2018, the year before the Lavinia Masters Act went into effect. After taking a moment to catch her breath, Masters says she “went off on the poor little man.”

“‘First of all, it’s not your money,'” she remembers telling him and, by extension, the crowd. “‘It’s not coming out of your paycheck. Second of all, you don’t know if they’re alive or not. If they’re not, you still owe the family.'”

Afterward she told Neave, “‘If this county has this mentality, how many other counties have the same mentality?'”

Both agree that the state may have to get tougher on counties that don’t comply. In fact, Neave says a state law enforcement agency that does not comply with the Lavinia Masters Act could have some grant funding pulled by the state government or the governor’s office. However, data from late 2021 shows that over 1,000 kits had been sent to labs between September 2019 and late November 2021 but not analyzed within the 90 days required.

“I don’t believe the numbers,” Masters says. “I believe they’re greater, because some counties may not report their numbers. Some of them are just being straight defiant, and some of them are just lazy, and they figure ‘Look, we’re a small town, and we’ll do it in our own time.’ And that’s the culture we help form by leaving kits on the shelf.”

While labs like Othram do critical work to solve cold cases, they alone can’t solve states’ flawed response to sexual assaults. A recent study by the Kaiser Family Foundation found that, in many cases, survivors end up paying hundreds of dollars for the medical work conducted after their assault. Federal law requires that the cost of conducting a rape kit be covered by the state, but only 14 states will cover the cost of actually processing that kit. Texas is not one of those states. Texas also does not cover the cost of a post-rape pregnancy test, a test for STDs, or STD medication.

A survivor of rape in Texas may be forced to shell out money for contraceptives and a test for sexually transmitted diseases, and even after all that, their own county may not process their rape kit.

**

Masters’ longtime disdain for law enforcement made the governor’s task force a team of strange bedfellows. The team includes several of people from the worlds of politics and criminal justice and, by Masters’ own admission, she “made a lot of enemies.”

“When I first started on the task force, I came in being me, and being me means having that voice that will not be silent any more,” she says. “The life I once lived in silence was dark and tormenting. To think that no one hears us or sees us … those days were past us. My days of being a victim and sitting on a shelf are over. That is not fair.”

“The life I once lived in silence was dark and tormenting. To think that no one hears us or sees us … those days were past us. – Lavinia Masters

“‘If these were your daughters and your mamas and your sisters,'” she told the task force, “‘you would be doing everything in the world.'”

She is proud of the voice the task force has helped give survivors like herself, and she is now thinking bigger: She wants legislation like the Lavinia Masters Act on the federal level.

At the same time, given recent legislation, it’s fair to wonder how the governor’s office can live up to its vision of “[leading] the nation” with an “effective, survivor-centered, trauma-informed response to sexual violence.”

Specifically, academics, experts and advocates argue that laws like Senate Bill 8 and, more broadly, the backlash against abortion can harm rape survivors and even curb reporting. As illustrated by a late 2021 story from NPR, this backlash has recently intensified in a way that is out of step with public opinion in Texas and throughout the country – and even with many in the Republican Party.

“For decades, public opinion – even in Texas – has been pretty consistent about allowing some exceptions to laws that restrict abortion,” the NPR story notes. The article quotes Carole Joffe, a professor and sociologist who studies abortion policy at the Bixby Center for Global Reproductive Health at the University of California, San Francisco. Joffe told NPR that, “despite public opinion on the matter, most of the anti-abortion bills introduced across the country in recent years haven’t included exceptions for rape or incest.

“I think what Texas shines a bright spotlight on is what disdain we have for the needs of women and girls, or people who can get pregnant even if they don’t identify as female,” Joffe said. “The kind of restrictions we are seeing are the product of growing power in state legislatures of the anti-abortion movement.”

The same story goes on to note that “the problem of pregnancies arising from sexual assault is not a small one. One study estimates that almost 3 million women in the U.S. have become pregnant following a rape.”

And according to the article, that “growing power in state legislatures of the anti-abortion movement” started happening in Texas roughly 10 years ago – right around the same time the state’s backlog of 20,000 untested rape kits came to light. That revelation gave even more steam to the work done by Masters and Neave, work that is drastically different from the anti-abortion movement, but also inextricably linked.

“The survivors, workers, and advocates I spoke to are concerned that, as abortion is restricted, people with uteruses may face less access to other basic medical care and may be deterred from reporting their abusers or undergoing rape testing, lest it be used against them if they ever become pregnant and wish to terminate,” Herchenroeder wrote in The New Republic.

If the anti-abortion movement continues to dominate the Texas Legislature, more survivors’ advocates might share those worries. That said, it might be foolish to bet against Masters, who has already proven an ability to do the unthinkable: unite Democrats and Republicans.

“In regard to the Supreme Court’s recent decision, I was very disappointed that they had no consideration for victims of rape, sex trafficking, incest and a woman’s serious health conditions,” Master says. “I believe that this should be an option for the victims of these circumstances if they so choose to exercise their rights after their trauma.”

She says she feels the same way about the restrictive abortion law signed by Gov. Abbott.

“This subject matter has been brought up to the task force and is still in talks on how we can empower victims after such a devastating blow.”