Glenda via Shutterstock

Audio By Carbonatix

Yesterday, Dana Goldstein, who covers a lot of things for The New York Times, including education, took note of Dallas schools in a story about reform efforts here, calling Dallas, “a national leader in trying to figure out how to encourage students of all backgrounds to willingly go to school together.”

She describes several innovations here as models for ways big urban districts may be able to re-desegregate themselves after being left high, dry, poor and minority by a half-century of white defection. Goldstein quotes Richard D. Kahlenberg at The Century Foundation:

“What’s exciting about what Dallas is doing is you have a district that’s 90 percent low-income. So many people look at that and say, ‘Therefore, we can’t integrate.’

“That’s not right,” he says. “You can begin with a small subset of schools and try over time to build the reputation of the school district among middle-class people.”

Goldstein also locates one of the city’s bright young new leaders, Andy Stoker (the Rev. Andrew C., actually, but I knew him when he was a kid), senior minister of First United Methodist Church downtown. Stoker tells her most of his congregation send kids to private schools, but he sends his two to Dallas public schools. She identifies his kids as white.

As soon as I read it, I thought, “Well, I bet Andy wouldn’t identify his kids as white. He would probably say they are Methodist.”

Listen, as someone who has labored away here locally on school issues for a very long time, I have been kind of waiting for the great national eyeball to spot Dallas as a center of school innovation. I know that the work achieved here under former Superintendent Mike Miles in the area of teacher merit pay was a serious advancement on earlier iterations in Baltimore, D.C. and elsewhere, based in significant degree on lessons learned in those cities.

School reform here has not been strictly idiosyncratic or a reinvention of other people’s wheels. Miles is a national figure in school reform, and the people he brought to Dallas with him were part of the national flow of ideas. But things were accomplished here that have not been accomplished elsewhere, and personally I’m thrilled to see Dallas getting some attention for it.

I also have to say that seeing the piece in the Times at this point in time was an experience fraught with irony for me, because I am aware that a lot of the Dallas reforms Goldstein writes about are actually in peril now in a period of retrenchment.

A month ago I was in Charleston for my son’s wedding, walking down King Street on a hot afternoon looking for a shirt, a mission directed by my wife, when I cheated a little and called Miles. Look, I was just walking, walking, walking with nothing else to do until I got there. So I got him – not always easy to do – and I asked him how he thought things were going in Dallas since his departure two years ago. Our conversation came back to mind when I saw The New York Times piece yesterday.

He was very wary of talking about a place from which he had been absent for two years.

“I’m not there,” he said, “so one should be careful about criticism or analysis from several hundred miles away.”

But, yeah, it sounded to me as if he’d been hearing pretty much the same things about Dallas that I was hearing.

“I don’t think the culture continued on the path or the trajectory we had hoped it would with regard to creating a culture of innovation,” he said.

Since “culture of innovation” is one of those phrases, I pressed him to be a little more English-languagey about what he thinks his regime accomplished and what he worries may be at risk.

“There has to be a continuous improving and changing of the system. That was the model we tried to put in place. It was important, and I don’t see that trajectory going in the right direction.” – Mike Miles

“You have to build a culture that is able to look at reform and innovation in a continual fashion,” Miles said. “That is one of the things we tried to do. It is distinctly opposed to a culture of patronage, a culture of status quo, a culture of ‘gotcha’ if you do something wrong. I think we made a little bit of headway there.

“There has to be a continuous improving and changing of the system. That was the model we tried to put in place. It was important, and I don’t see that trajectory going in the right direction.”

He said something to me – I was dodging buses, you know – about “an educational ecosystem of reform,” another phrase, so when I got to a safe curb, I asked for English again.

“Probably the best example is Denver,” Miles said. “A superintendent and board cannot make the kind of systemic change that is necessary for public education by themselves. It’s too hard. There are too many vested interests and not enough political will.”

He ticked off a list of private and civic organizations in Denver focused on schools, all of them constantly pushing the school board and administration toward reform.

“This week, for example, I was at an A+ Colorado meeting. They had done a report on the state of Denver schools. They were pushing Denver to do even more.

“We had hardly any of that in Dallas. We had Commit. Commit started as a budding organization the year I got there. Stand For Children was not around until my last year.”

So “culture of innovation” and “educational ecosystem of reform.” Two phrases. I was kind of hoping, walking around a strange city looking for a shirt, those might be all the phrases I would have to ingest, but then Miles told me the third thing he believed his regime had worked toward in Dallas: “changing the employee value proposition.”

Oh boy. About then, I was betting I would get back to the motel with something my wife wouldn’t even let me wear.

But he ran it down for me. It’s about making sure that the system for paying teachers hooks up directly with what the district wants them to achieve, so there’s no ambiguity. Do this, better pay. Don’t do it, no better pay. It’s the system otherwise known as merit pay.

“We at least identified that we value student achievement,” Miles said. “We valued what the students think about the teachers from a survey and what the community thought was important. We valued growth, and we valued high-quality instruction.”

But the same coin had another side – the side that conveyed what the district did not value.

“We did not value, as much, years of experience or college degrees and advanced credits,” Miles said.

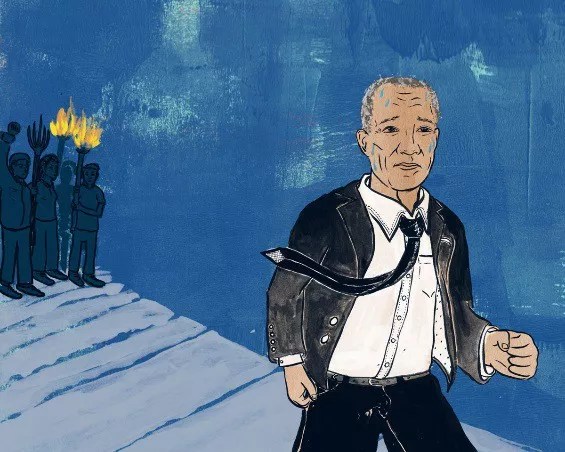

Of course, it was right there – at that particular interface with reality – that the gunpowder supply blew up. The teachers unions here, as they have nationally, launched a campaign to the death against the abandonment of seniority pay. Hispanic leadership supported Miles, but older black leadership in southern Dallas, which regards control over school jobs as fruit of the local civil rights struggle, was furious. When Miles cut ministers and other established community leaders out of the hiring of principals, he might as well have been driving around town at night shooting out church windows.

When former Superintendent Mike Miles did away with seniority pay and Tammany Hall-style patronage, out came the torches.

Daniel Fishel

When things got too hot and Miles finally got pushed out, Michael Hinojosa, a Dallas native and popular former superintendent with great community relationships, was brought back for a second term with an explicit mission of calming the waters. When I spoke to Miles while I was on my own explicit mission that day in Charleston, he was understanding of the mandate of peace that the community had handed his successor.

But he pointed out that the ideas and the dynamism of meaningful reform only move in one direction. Call it peace, call it taking a powder – the fact is that backward is backward. Miles told me he is worried that Dallas is losing ground that was very hard fought, gained only at significant social political cost. He spoke in particular of a recent effort to put elements of seniority pay back into the merit pay system.

“What I see, though, in this latest effort and the district agreeing to it is they are flattening and confusing the message about what you value,” he said. “If you are a teacher now who is ‘proficient’ [a graded rank] and you have survived a year at that level, you are going to get a raise. That is no different than a teacher salary schedule where you get a raise every year for doing the exact same thing.”

In the end, Miles said, all of the phrases above are tools to allow the schools to accomplish one great goal. And that, wouldn’t you know, right in front of the shirt shop, was two phrases: “personalized learning” and “changing the instructional paradigm.”

“We have to change the instructional paradigm,” he said.

Of course, I asked for help. He explained.

“It cannot be 25 kids in rows with the teacher directly instructing reading, writing, math, science and social studies,” he said. “Personalized learning is a different way. It’s not just kids learning at their own pace.

“It’s not as simple as that. It’s taking advantage of the kids’ strengths and tapping into those strengths and their interests. It’s pushing that, so kids who are ahead can accelerate or learn other things they need to learn and kids who are behind can get a little bit more time and more individualized attention.”

To accomplish all of those phrases, he said, you have to be able to identify teachers closely by ability and you have to be able to motivate them.

“If you start watering down what ‘proficient’ looks like, if you start watering down the incentives, that’s not selective enough,” Miles said.

Anyway, I found the shirt. I’m glad The New York Times found Dallas. Maybe some attention and some kudos will help stiffen the spines of the people here who are still fighting the good fight for better schools. I think those warriors may need all the help they can get.