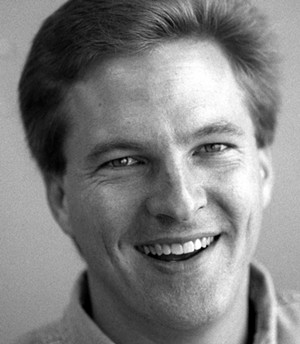

“I just wanna say that yes, in fact, I do know how lucky I am,” says Wally Lynn, arms and heart wide open as he and his cup of Jack Daniel’s welcome a couple hundred guests to his 40th birthday party. “To have all y’all here, and to have experienced some of the wonderful things in my life ... I am truly blessed.”

With that, the man who has everything — fame, fortune, family and friends — gets a special gift from his wife, Kim, for this 2001 gala. She has arranged for a live concert by one of her husband’s favorite Texas musicians, Trish Murphy.

In his bank, Lynn owns shares of Yahoo stock worth $4.4 million.

On his mantel, he boasts numerous awards from a 15-year sports broadcasting career in Dallas-Fort Worth and a plaque commemorating his cameo speaking role in Oliver Stone's movie Talk Radio.

In his Allen home’s garage, he possesses multiple BMWs.

At the Plano restaurant Love & War in Texas, he has permanently reserved seats at the bar.

Under his wing, he cherishes his doting wife and two gifted sons.

Today, he’s piling on his embarrassment of riches by spotlighting his newest showpiece — a 77-acre ranch in Spicewood, just west of Austin and around the bend from Willie Nelson’s annual Fourth of July picnic. The spread features a main house with an outdoor shower and screened-in porch. Dotting the property are 100-year-old oak trees, plentiful deer, a boat for playing on the nearby Colorado River, a fleet of ATVs, a basketball court, a Wiffle ball field, homemade potato cannons, horseshoe pits, barbecue smokers and a large entrance gate painted like the Texas flag.

Welcome to Wallywood.

This ranch will eventually host concerts by Texas country artists Mike Graham, Roger Wallace and Cooder Graw, but tonight it’s the setting for the birthday boy to be sultrily serenaded under the stars. Torches and a fire pit strike the mood. The mammoth rock provides the stage for Murphy’s acoustic crooning.

Says Lynn, understandably beaming, “It doesn’t get any better than this!”

He has no idea.

Over the next 17 years, Lynn will endure one of the saddest, most dramatic riches-to-rags falls from grace in Dallas media. His nosedive will be littered with suicide, adultery, alcoholism, hospitalization, divorce, foreclosure, bankruptcy, embezzlement, arrests and a shattered surrender that leaves him hapless, homeless and wholly unrecognizable.The trouble with trouble is, it starts out as fun.

tweet this

As a longstanding nod to his dizzying and confusing collage of projects, friends of Walter McMillan Ralph (he adopted the stage name “Lynn” to honor his mother) dubbed him “Waldo.” Like finding his cartoon character namesake, pinpointing where Waldo is and how he got here is difficult.

Perhaps it begins tonight at Wallywood, with a verse from Murphy’s new hit single, “The Trouble With Trouble.”

The trouble with trouble is, it starts out as fun.

Where’s Waldo?

There he is. Growing up in Lake Highlands. Showing off in every crowd.

“He just had it,” says Jeff Coats, Lynn’s best friend since third grade, college roommate and best man in his wedding (and vice-versa). “He was the fastest guy in track. The funniest guy in class. He was just good, naturally good, at anything he did.”

The youngest of four siblings to parents Lynn and Pierson, Wally is decent at playing sports but delirious about talking sports. By the seventh grade at Lake Highlands Junior High in Northeast Dallas, he carries a hallowed spiral notebook. In it are crucial data — names, stations, air times, call-in phone numbers — about every radio and TV sports show in town. It’s his hand-scribbled, pre-internet version of bookmarked websites, and it’s only a glimpse of his ingenuity.

“He was so quick, so witty, so funny,” says Anecia Drake, whose friendship with Lynn has persevered since 1974. “He could talk sports. He knew all about music and bands. Honestly, I think we were always secretly in love. But we were buds first, and we didn’t want to screw that up.”

As an adult, Lynn flawlessly plays Billy Joel on the piano, sings an eerily Sinatra-sounding Sinatra and — at the drop of a hat — performs spot-on impersonations of DFW sports icons Nolan Ryan and Michael Irvin. He never has a single music lesson yet plays the keyboard with Graham, strums a guitar alongside Murphy and produces a surprisingly infectious beat on a dilapidated washboard with Cooder Graw.

He even somehow teaches music.

When his youngest son, Mitchell Ralph, gets intimidated at the prospect of competing against a classically trained pianist in a junior high talent show, Lynn engages him with the family’s grand ivories. No sheet music. Just a laptop, finely tuned ears and talented fingers.

“I’ll be damned if Mitchell didn’t win that contest,” Kim Ralph says. “He beat the kid that played Mozart! By playing the theme from Rugrats. Rugrats! Wally just had a special talent to pick things up so easily and then put his little spin on it.”

Where’s Waldo?

There he is. Behind the microphone. Ahead of his peers.

A Southwest Texas State alumnus, Lynn starts his radio career working a political beat at the Capitol in Austin, but it’s mainly a resume fluffer to take him where he’s always dreamed of being — talking sports in DFW.

“The guy could do it all,” says Hitzges, who worked with Lynn at KLIF before jumping to rival The Ticket in 2000. “If the situation called for it, he’d be goofy as all get out and make the audience laugh.”

While other shows talk vanilla football, Lynn colors outside the lines and features two obscure Cowboys offensive linemen, Dale Hellestrae and Mark Tuinei. The award-winning bit of the Snapper and Pineapple Show stars Lynn’s live play-by-play (using a multitude of seamless impersonations, including Cowboys owner Jerry Jones and iconic national broadcaster Jack Buck) of Hellestrae, the team’s long-snapper, zipping a ball into the rear window of a car driven by Tuinei through the players’ parking lot at Valley Ranch at 35 mph.

Although he later anchors Cowboys postgame shows on 103.7 KVIL, 98.7 KLUV and 105.3 The Fan; works for ESPN stations in Dallas and Austin; creates a Texas music Front Porch show for 99.5 The Wolf; and becomes the official radio voice of Southern Methodist University, the Dallas Sidekicks and Dallas Desperados, Lynn consistently highlights two moments of pride: being the voice of the 2005 Ring of Honor induction ceremony for Troy Aikman, Michael Irvin and Emmitt Smith at Texas Stadium, and “the snap segment.”

“To think of something like that was crazy,” Lynn says. “To pull it off was even crazier.”

Based on the beauty in Lynn’s balance, there are no signs the homer will ever be homeless.

Despite working long hours that often require travel, he maintains passion for his marriage and quality time for his sons. He takes his oldest, Jake Ralph, to Cameron Indoor Stadium to watch a Duke basketball game. He coaches Mitchell’s baseball team, never missing a game.

“For the first 16 years of my life, he was Super Dad,” Mitchell says.

Where’s Waldo?

There he is. Popping Champagne. About to burst his bubble.

By the late 1990s, Lynn is enjoying sustained career success and the fruits of his relentless networking. A fan of his makes an introduction, which leads to him being one of the first 20 hires at a Deep Ellum startup company called AudioNet, with a boss named Mark Cuban. Engineered primarily as a way to hear college sports events over the internet, the company covets Lynn’s voice talents and eclectic DFW connections.

“It’s going to turn your computer into a radio and a TV,” Lynn tells friends about his new endeavor in 1995. “I think it could be big someday.”

That time arrives in July 1998. AudioNet rebrands itself Broadcast.com and goes public, with a record IPO that sends stock shares soaring 250 percent. Nine months later, on April 1, 1999, Yahoo purchases Broadcast.com for $5.7 billion.

Cuban instantly becomes a multibillionaire and begins eyeing ownership of the Dallas Mavericks. Lynn becomes a Yahoo employee, with stock shares worth $4.4 million.

“Pinch me! No, fucking punch me!” Lynn exclaims as he and a limousine full of friends celebrate on Belt Line Road in Addison. “Can’t believe this is real livin’!”

While Kim is cautious with the potential windfall — “I didn’t quit my job or even go crazy enough to buy a new mattress,” she says — her husband is intoxicated by his new tax bracket.

Lynn pays off his cars and house and makes a significant down payment on the $600,000 ranch. He continues speeding toward happily ever after through his birthday bash with Murphy and into 2002. It is here when something — karma? bad decisions? — triggers a bewildering series of unfortunate events that will ultimately strip him of all luxuries and erode everything he treasures.

It arrives in waves of death.

Of his radio career.

In streamlining its stations in 2000, DFW radio cluster owner Susquehanna makes The Ticket its lone sports station. The decision turns KLIF into a news outlet and ends Lynn’s 13-year career as its sports voice. He goes to ESPN Dallas and ESPN Austin and returns to 105.3 The Fan for cups of coffee, but for the most part only dabbles in public relations gigs representing local athletes such as Charles Haley and Tatu and mentalist David Magee.

“He got too big for his britches,” Kim says. “One night, we fought about it, and he looked me straight in the eye and said, ‘I’m not like you people. I refuse to work 9 to 5.' So he didn’t have a steady paycheck for 10 years.”“He got too big for his britches. One night, we fought about it, and he looked me straight in the eye and said, ‘I’m not like you people. I refuse to work 9 to 5.' So he didn’t have a steady paycheck for 10 years.” – Kim Ralph

tweet this

Of his fortune.

After the dot-com bubble bursts, Yahoo eliminates its broadcast services in late 2002, and Lynn is trimmed as part of mass layoffs. Gone are his job and much of the unvested stock that adorned it. Of the $4.4 million stock potential, Lynn realizes about $500,000 in cash. He is forced to sell Wallywood in 2005 and, after a slew of unsuccessful investments, eventually takes out a $100,000 home equity loan.

Of his friends and family.

By 2000, one of Lynn’s closest friends is Dallas construction mogul John Haines, a principal owner of Ridgemont Construction and the husband of Kim’s cousin Leslie. The two share business dreams, compare expensive toys and embark on guys’ trips to watch Haines’ Nebraska Cornhuskers play at Notre Dame and Lynn’s Cowboys play the Packers at Lambeau Field. Besieged by a sagging economy and marital problems, Haines kills himself on Aug. 20, 2008.

“Losing John obviously hurt everyone,” Mitchell says, “but the one that really began pushing him over the cliff was [his] mom.”

She dies in 2011 at age 89. In the span of three years, Wally Lynn loses two heroes.

Of his marriage.

Exhausted by her husband’s chronic voids of affection and employment, in the summer of 2010, Kim moves out of their Allen home. They divorce in 2011, one month shy of their 23rd anniversary.

“I was lonely,” says Kim, who admits she was unfaithful. “My husband hadn’t paid attention to me for a long, long time.”

With Kim gone and Jake off to college at the University of Texas, it is just Lynn, Mitchell and a new, unwanted squatter. The drinking demon that netted Lynn a DWI in 2009 is blossoming into a raging monster.

“I started finding empty wine bottles all over the house,” Mitchell says.

Where’s Waldo?

There he is. A recluse. In refuse.

By 2012, Lynn is a hermit. His drinking is escalating, his socializing evaporating. After he hits his son’s car in the driveway while driving drunk, Mitchell adds to his daily chores.

“Had to hide his keys every morning before I left for school,” he says. “On weekends, he’d be drunk by the time I woke up.”

On several occasions, Mitchell calmly challenges his father.

Mitchell: “Dad, whatcha drinking?”

Lynn: “Water.”

Mitchell: “Really? That sure doesn’t look or smell like water. You sure?”

Lynn (through bloodshot eyes, slurred speech and rising anger): “Yes. I promise!”

“That broke my heart," Mitchell says. "Drinking was more important to him than being honest with me.”

When Mitchell leaves for college in fall 2012, Coats, a Collin County Realtor, persuades Lynn to sell his house. So detached is Lynn that he refuses to pack, one day calling friends to announce a free fire sale that includes his beloved piano.“Had to hide his keys every morning before I left for school,. On weekends, he’d be drunk by the time I woke up.” - Mitchell Ralph

tweet this

“Come take it,” he says to multiple friends. “I don’t want any of this shit anymore.”

After discovering the house is on the verge of foreclosure, Coats does the heavy lifting. He organizes an estate sale, secures a storage building near The Golf Club at Twin Creeks for the bulk of Lynn’s remaining stuff and helps him rent an apartment in north Plano, just off the Dallas North Tollway and less than 100 yards from Coats' house.

“He was going downhill pretty fast,” Coats says.

Six months later, Coats receives a call from the storage company. Lynn was a couple of months behind on his rent, and the unit was about to be seized, its contents sold as compensation. Notified of his possessions’ peril, Lynn shrugs.

“Fuck it,” he tells Coats. “Let 'em have it.”

Included in the belongings: every family photo album and video, engraved and antique silver passed down through generations of his family, even some of his mother’s award-winning paintings.

“I get nauseous just thinking about it,” Kim says.

After a lengthy period of silence, Ben Ralph visits the apartment to find his brother on the floor, motionless, in a stupor. The following morning, he drives Lynn to the Serenity House treatment center in Abilene. Upon intake, staff members call 911, and Lynn is rushed to a nearby hospital’s ICU with alcohol-induced encephalopathy (swelling of the brain and disorientation). He stays there for 30 days before back-to-back rehab stints in both the Abilene and Fredericksburg centers of Serenity House.

Upon his return to DFW, he tells friends about his moment of clarity.

“It’s pretty scary stuff, what I did to myself,” Lynn says. “I’m lucky to be alive.”

It is dramatic.

It is bullshit.

In May 2016, another spell with zero communication.

Ben and Leslie, Kim's cousin, arrive at the apartment for a welfare check. No answer. They summon Coats, who brings a duplicate key.

The place is filled with what Ben estimates “must’ve been 1,000 beer cans.” Coats says the garbage — pizza boxes, unsecured trash bags and rotting fast food — rose from floor to countertop. On a table is an eviction notice next to several uncashed checks written to Lynn from his father, Pierson.

“The whole place was a biohazard,” Ben says.

Lynn’s condition is even more gruesome.

They find him lying on the bathroom floor next to the base of the toilet, covered in feces, urine, confusion and the unmistakable stench of Idon’tgiveashit. He is seemingly paralyzed, only able to marginally move one hand while repeatedly muttering, “Gotta find my shoe … .”

“He was on the brink of death,” Leslie says. “Emaciated almost beyond recognition. Totally immobilized.”

The paramedics estimate Lynn has been in that prone position on the floor for more than 24 hours and would have been dead in three or four more. He is taken to Plano’s Texas Health Presbyterian Hospital but walks out in the middle of the night and shows up at Coats’ house the next afternoon.

“Drunk and scared,” Coats remembers. “He said, ‘I’m broke, and I don’t know what to do.’”

Coats rents a room at a nearby hotel and provides fresh clothes. He tells Lynn he will be back in a few hours, asking him to be showered, dressed and prepared to turn over a new leaf. When Coats arrives, he finds Lynn sprawled over the bed in the same clothes and with the distinct smell of youknowwhat.

“At that point, it was hard to tell if he was freshly drunk or just residual drunk,” Coats says. “Either way, that was it. I was out of options. He was out of options.”“At that point, it was hard to tell if he was freshly drunk or just residual drunk. Either way, that was it. I was out of options. He was out of options.” – Jeff Coats

tweet this

Coats throws Lynn in the shower and takes him to his house, where Coats packs a suitcase full of clothes and toiletries. Then he makes the most difficult drive of his life. He takes his best friend to a homeless shelter.

As he leaves Lynn at The Bridge in downtown Dallas, Coats begins bawling.

“I felt like a total loser,” he says. “But in this situation, there are no winners.”

The plan is for Lynn to receive professional help at The Bridge Homeless Recovery Center near Dallas Farmers Market. Friends and family commit to checking on his progress, to visiting him. He is admitted on May 17, 2016. On May 20, according to a volunteer, Lynn has a shower, a hot meal and … poof.

Just like that, he is gone, blending into the unseen sea of Dallas’ almost 4,000 homeless people. Qualifying for neither an Amber nor Silver Alert, Lynn is simply a missing person.

“At first, I figured he’d just show up at my house,” his brother says. “But after a couple weeks, I couldn’t stand the thought of him out there. Had to try something.”

Looking for a broken 55-year-old man who has been in and out of hospitals and rehab and likely will refuse their help, Ben and Coats recruit friends to spread the word about Lynn’s status. There are daily searches downtown. A report circulates in the local media, which prompts public interest, offers of free services from off-duty Dallas police officers and private investigators, and social media sharing from an array of former Lynn associates, including Hellestrae, Hitzges, Fisher, Dale Hansen, Mike Rhyner, Newy Scruggs and Cuban.

“That’s horrible,” the Mavs owner writes in an email after reading of Lynn’s disappearance. “Anything I can do to help just let me know.”

On July 1, a worker at Hitzges’ charity of choice, Austin Street Shelter, alerts the talk-show host that Lynn has been located. Hours later, Lynn borrows a cellphone and calls Ben.

After 44 days on the streets, Lynn says simply, “I’m ready to come home.”

There he is. Surprisingly sober. Shackled.

As Lynn moves in with Ben in Fairview, his support system is reinvigorated. Friends launch a GoFundMe campaign that raises almost $6,000 to help pay for clothing, luggage, a cellphone and laptop computer. A McKinney dentist provides free services. Peers who have experience battling addiction, including former Dallas Stars play-by-play voice Ralph Strangis, reach out to help.

Writes Strangis to Lynn, “It might just help to have another addict in the room to talk to.”

In an attempt to convince Lynn that people are still rooting for him despite his bad decisions and worse consequences, friends print and demand he reads 300 pages of well-wishes sent via email, text and social media messaging during the search.

“I’m shocked by this outpouring,” Lynn says. “It’s embarrassing, actually.”

His debt is being paid down, his spirits lifted up.

Until he finds himself in jail.

In late September 2016, Collin County sherriff’s officers show up at Ben’s door with a warrant. Lynn is taken away in handcuffs. In a phone call to a friend from jail, he attempts to explain.

“I had some unpaid tickets for sleeping in public, things like that,” Lynn says. “Not that big of a deal. I hope.”

It is a lie to cover up a bigger lie.

Lynn isn’t behind bars for snoozing on a park bench, but rather for embezzlement against his family. The official charge is misapplication of fiduciary or financial property between $30,000 and $150,000, a third-degree felony.

Suddenly, shockingly, the family gets its answer to how Lynn made ends meet without a steady job. Leslie’s suspicion is what led her to accompany Ben to Lynn’s apartment earlier that year.

“I heard through family he wasn’t doing well,” Leslie says. “I tried to contact him, and when he finally responded, he said he was going to be 'out of pocket’ for a while. I’ll admit, I was a little nervous about the man overseeing my children’s trust fund.”

After John Haines' death in 2008, his construction company partners bought out Leslie’s stake. Part of the package was a $200,000 trust fund for the Haineses’ two children to be controlled by a close friend or family member of John’s — Lynn.

“He was a father figure to my kids,” Leslie says. “We had already put Wally in our will in case something happened to us.”

With Lynn designated as the lone signee on the account, Leslie is unable to check either the individual transactions or the balance. It isn’t until she hears him connected to terms like “addict” and “rehab” that she turns proactive.

Amid the filth of the apartment, Leslie finds statements detailing multiple linked accounts to different banks, confirming her worst fears. Her children’s trust has significantly dwindled after repeatedly being drained by transfers to an account belonging to Lynn.

“This was no longer just a sad story,” Leslie says. “It was a scam to steal money.”

She takes her findings first to the hospital, where she confronts Lynn and gets a videotaped confession and apology. Then she goes to Plano police, where detectives subpoena all involved accounts and corroborate the crime.

The conclusion: From 2013-15, Lynn transferred $70,000 in increments of $5,000 to $10,000 from the Haineses’ trust fund into his personal checking account. That alone isn't necessarily a crime, since he is authorized as the sole signee, but the investigation reveals that Lynn’s account was opened with a deposit from the trust and that correlating purchases were for rent, utilities, groceries and alcohol, not for the betterment or benefit of the trust.

Lynn was charged in June 2016, and a warrant was issued for his arrest. By that time, perhaps not coincidentally, he had disappeared into Dallas. Preparing for him to resurface, Leslie provided police the names and addresses of his closest friends and family, leading to the visit to Ben’s.Lynn transferred $70,000 in increments of $5,000 to $10,000 from the Haineses’ trust fund into his personal checking account.

tweet this

“I wanted to give him the benefit of the doubt,” Leslie says. “Maybe at first he was just going to borrow some money, with plans to pay it back. Then maybe he got in over his head? All I know is the Wally I knew would never do this to my kids.”

Lynn sits in jail in McKinney for 75 days. Leslie helps negotiate his release, pleading with the district attorney to allow Lynn to work and pay back his debt rather than be locked up.

He pleads guilty and is sentenced to 10 years in prison but receives probation dependent upon him maintaining gainful employment, paying regular restitution to the trust and reporting monthly to a probation officer.

With a job in the offing, roof over his head and pillow under it — all thanks to his longtime friend and millionaire entrepreneur John Eckerd — Lynn spends late 2016 and early 2017 daring to dream about his future.

He mulls launching a podcast. Ponders how he can acquire a car. Attends a Christmas party with friends. Spends time with family, even briefly reconnecting with his sons. He drowns his sorrow over a Cowboys playoff loss not with alcohol, but his other vice, country music.

It’s a long way from the millions and the radio and the ranch, but it suffices for happiness.

“I can’t believe what I’ve been through,” he tells a group of friends sitting around the party’s Christmas tree. “What I’ve put people through. There’s no way I can ever make up for it.”

Where’s Waldo?

There he is. In lethargy. Out of options.

By the spring of 2017, Lynn’s motivation is AWOL, and destitution is increasingly becoming his destination.

Eckerd, the latest in a long line of helping hands, provides his friend with a simple job and a sterling shelter, his $1.2 million guest house in McKinney.

The caveat is the job. All Eckerd asks of Lynn is to check with him each day before 9 a.m. to see what help is needed. To earn a paycheck, begin restitution to the Haineses’ trust and fulfill the terms of his probation, Lynn simply must be available and stay accountable.

It’s too much to ask.

During his three months in the house, he meets his job requirement fewer than 10 times. There are no signs of alcohol, but also no glimpse of gumption. When chided by Eckerd about shirking his nominal duties, Lynn listens and nods and agrees and understands and rarely awakes before noon. Similarly, Lynn never responded to Strangis.

“Beyond frustrating,” Eckerd says. “People are giving him every opportunity to get back on his feet, but the old Wally just isn’t there. There’s no light in his eyes or fire in his belly. You can’t help those who refused to be helped.”

By August, Eckerd prepares to sell the guest house. Long since weary of wasting energy and expenses on Lynn’s aloofness, he tells him to move out.

“I reiterated that I tried to help and that he hadn’t held up his end of the bargain,” Eckerd says. “But he just shrugged and mumbled. If I didn’t know better, I’d think he didn’t give a damn.”

Says Lynn of his post-Eckerd predicament, “It’s going to be real hard to find a job without a car.”

The consensus: No matter what his support group does, Lynn will focus on living low, getting high and running from his past, in turn sabotaging his future.

“I don’t think this movie ends well,” says his friend Anecia Drake. “I hope and pray that I’m wrong, but I just don’t see him snapping out of it.”

Where’s Waldo?

There he is. Fleetingly in a hotel room. Forever incognito.

Lynn’s bleak options are a transient existence of covert bouncing among homeless shelters or 10 years in prison for absconding on his probation in case No. 401-83250-2016-2. Because he’s paid back only $3,000 of the $70,000 he siphoned and has stopped meeting his probation officer, the Collin County Sherriff’s Office issues a warrant for his arrest Nov. 6.“I don’t think this movie ends well. I hope and pray that I’m wrong, but I just don’t see him snapping out of it.” – Anecia Drake

tweet this

“Dead or in prison,” Mitchell says. “I’ve been expecting one of those two phone calls about him every day for the last six years.”

With two weeks prepaid rent, $600 in his checking account, working cellphone and laptop, new bicycle and seven walking-distance job leads waiting in his email, Lynn checked into Room 103 of the McKinney Motel 6 on White Avenue at 10:30 a.m. Aug. 28.

No one has seen him since.

There is sporadic communication via Facebook messenger, but just 18 months after vowing to leave the streets, Lynn seems determined to win his game of hide-and-don’t-seek.

“Let’s face it, we rescued a guy who didn’t want to be saved,” Ben says. “What a shame. What a big give-up. It’s sad, but it also makes you mad.”

Homelessness is merely his trade-off for an off-the-grid life where hygiene is optional, time is irrelevant, past transgressions are muted and consequences can be ignored.

With financial support from family members cut off, Lynn has no known sources of income.

“I’ll love my Wally until the day I die,” Kim says. “But it’s the saddest thing ever because that person is gone.”

Says Mitchell, “Walter Ralph might still be alive, but my dad died a long time ago.”

Where's Waldo? There he ... isn't.