Courtesy Allen Development of Texas, LLC

Audio By Carbonatix

In sharp contrast to the bomb-throwing radical some whites may have taken him for in the past, the Dallas County Commissioner John Wiley Price whom people will see in a federal bribery trial next month may look more like the best friend rich Dallas white people ever had.

Next surprise: That will be why he’s on trial. The government will argue he’s been too good a friend.

But the federal prosecutors also will have to get around a big corner to convince jurors that Price deserves criminal punishment for that friendship, not the civic medal of honor the Dallas Citizens Council probably wishes it could give him. It’s Dallas, so you just never quite know until you get there.

One good example of that corner was highlighted again last week when documents were unsealed containing multiple references to something called the inland port in Price’s southern Dallas County district. It’s a topic that took up five full pages in the original 107-page indictment filed two and half years ago.

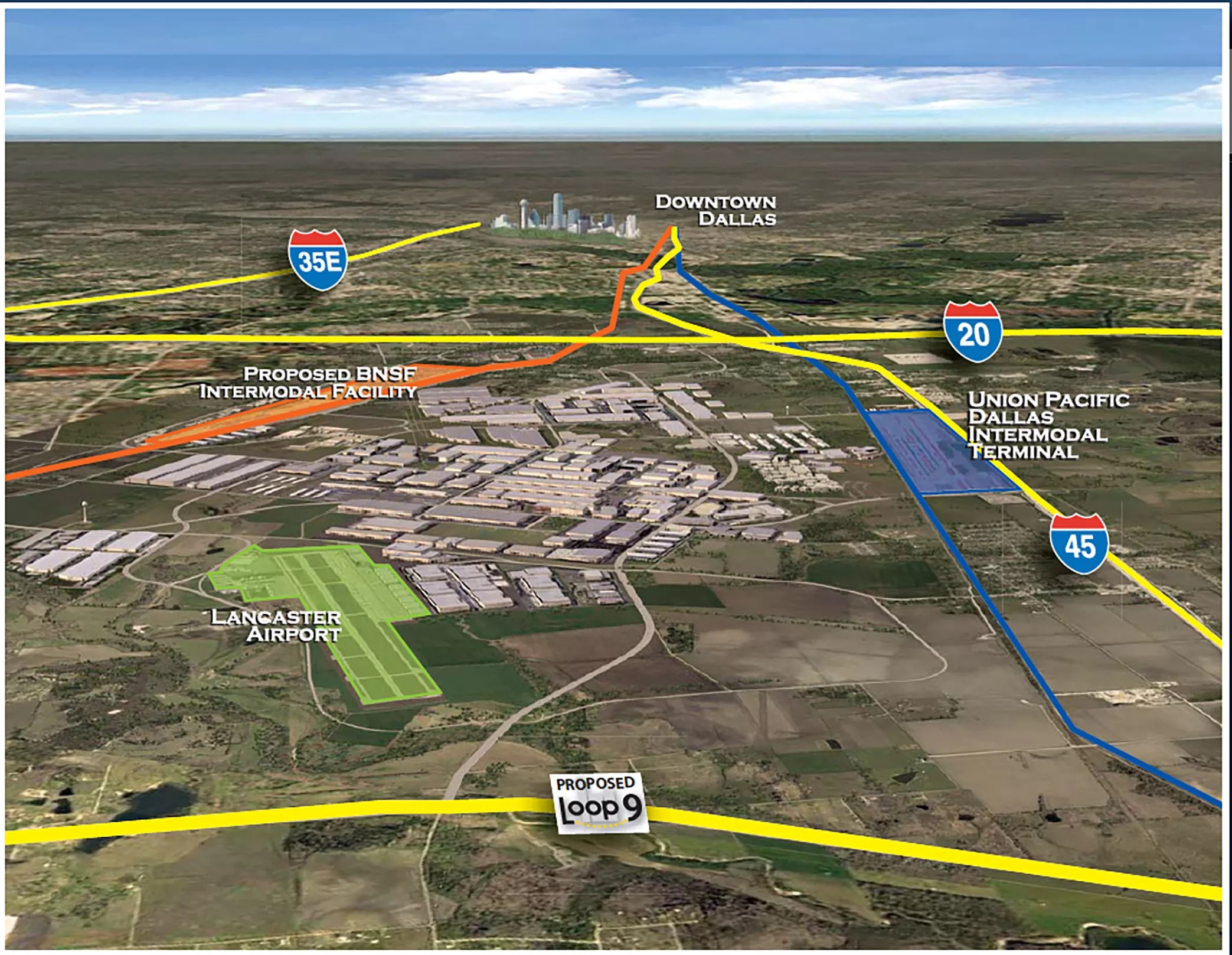

The inland port or Dallas logistics center was a proposed development intended to make southern Dallas the premiere continental shipping and warehousing hub for goods from China and the Pacific Rim moving from Pacific deep-water ports in California and Mexico to the American Middle West and Canada. A truncated version of it has been developed since, but Price helped starve and stave off the full vision, which would have competed with a similar shipping hub in Fort Worth controlled by the powerful Perot family of Dallas.

The question was always why Price, who built a political career on championing economic development for his district, would take up a public cudgel against the biggest and brightest promise of jobs and prosperity ever to come within 100 miles of southern Dallas. And why would he champion instead the cause of a business in an affluent area 20 miles north?

The answer broadly suggested but not spelled out in the indictment is supposed to lie in the fact that Price’s co-defendant, longtime political consultant and lobbyist Kathy Nealy, was pulling down a healthy retainer from the Perot family. In the same period, Nealy was shoveling a lot of cash to Price, buying cars for him and helping him buy land.

The Dallas Observer covered this story intensively nine years ago, by the way, and I noticed in last week’s documents that the government seems to have placed many of our stories in its evidence file. I always thought the stories we did were evidence of something far worse than criminality: political betrayal.

In his efforts to stall the inland port project, Price helped the old white establishment in Dallas do what it has done to southern Dallas since Reconstruction – sell it out, rip it off, kick it down, never let it lift an elbow out of the barrel. For that, he may or may not have been richly rewarded. He was certainly applauded.

The editorial page of The Dallas Morning News suggested it was Richard Allen, the California developer behind the inland port project, who was insensitive and out-of-step: “Going forward,” the paper said, “white-dominated companies must keep foremost in mind the unique history of southern Dallas. It is not simply a great business opportunity to be exploited for maximum profit.”

Obviously not. Maximum profit, according to hoary Dallas tradition, is always to be reserved strictly to the white northern areas, while southern Dallas can get by pretty well on humor and dance.

The North Texas Council of Governments, a federally mandated regional planning agency with powerful discretion over transportation and infrastructure dollars, rushed to Price’s defense, helping him hold up and hold hostage a key bridge project essential to Allen’s project. And while we’re on that topic, we need to pin down a little bit of mischief.

This was all about money. So this was all about time. Allen’s privately held firm sank X-many hundreds of millions into land, construction and legal work to bring their product – immense warehouses and shipping yards – to market on a certain timetable. He was right at that point, ready to ink deals with companies like Wal-Mart, Target and other major players, when the Perots looked over their shoulders and saw him coming.

Price went to work aggressively, moving to hold up the needed bridge project and stall an international trade zone. He even called for a total redo of five years and millions of dollars worth of planning and design that had already been done – a proposal that the NTCOG wholeheartedly endorsed.

Over the years The Dallas Morning News and others have disputed my version of these events. The News has gone to some lengths to cite instances in which they seemed to come down on the side of Allen and the inland port, as if all they ever wanted was some reasonable balance. But this was a horse race, not a séance. The Allen horse was a nose short of the finish line; the Perot horse was half a furlong behind; all of a sudden John Wiley Price wanted to inspect the Allen horse’s shoes.

How hard is it to figure that one out? But in order to prove a criminal conspiracy, the feds must demonstrate a quid pro quo, a tit for tat, a specific linkage by which a client pays a price for Price’s vote on a question.

In 107 pages of droning detail, the indictment of Price, Nealy and Price’s administrative assistant, Dapheny Fain, attempts to paint a certain pattern: Nealy gets money from clients. Then Price acts in the interests of those clients. Then Nealy gives money to Price.

But if you uncouple the timelines, you have three things going on simultaneously. In one timeline, Nealy is always getting money from clients. In another, Price is always doing things Nealy’s clients want to see done. And in the last, Nealy is always giving money to Price.

Two of those timelines bring us back into the grand old traditions of the white city. Consultants who help get people elected to office in Dallas almost always come back hat in hand to those same officials once they are in office and lobby them to vote in favor of clients who are paying the consultants’ fees.

Nealy was one of the consultants who helped get Dallas Mayor Mike Rawlings elected, handling his black campaign. The white election consultant for Rawlings, Mari Woodlief, wrote a plaintive column for The Dallas Morning News right after Rawlings’ election in 2011 urging City Hall not to pass ethics reforms that might impair this time-honored food chain. Woodlief argued that no one can be better qualified to carry the public interest to an officeholder than the professionals who get paid to do it.

Whether you agree with that or not, the point is that Nealy was well within local tradition and respect by helping Price win elections, going to clients who would have issues before him, getting money from them and then going back to Price on their behalf.

What about Price always voting the way rich white people such as the Perots would want him to vote? Well, for one thing, it wasn’t really always. But for another, one thing the casual observer may miss, especially by focusing too much on Price’s public street performances as a rabble rouser, is that old rich business guys often love Price.

When Dave Fox, a retired homebuilder and staunch conservative, was serving as county judge in the mid-1980s, Price was a new county commissioner. Fox told the editorial board of The Dallas Times Herald – in hushed tones as if it needed to be kept secret – that Price was actually very intelligent and understood road and bridge projects better than some engineers.

Price, for his part, has always had a bipolar relationship with white power, threatening to pull down the temple around his ears if he didn’t get his way with the rich white guys on Monday, preening and basking Tuesday in their approval. But the relationship and the understanding, even the simpatico, have always been ongoing.

The last of the three timelines would be the one in which Nealy is always giving Price money. Certainly if those transactions are viewed only in the context of politics, they present Price with his biggest challenge. After all, if Nealy is Price’s political consultant, he should be paying her, not the other way around.

But why should those payments be viewed only in the political context? Whether white people know it or not, there’s nothing terribly unusual or even surprising in the old southern Dallas black community about women giving money, clothes, even cars to a handsome powerful black man. This could be one occasion when a racial cliché works in Price’s favor.

He might even want to offer to demonstrate to the court why he’s worth a new car. I think the term for what the government might do in that event is “stipulate.”

Oh, and you may have noticed: They’re having a hard time figuring out if they can even try Nealy or not, since it turns out the government may have given her some kind of immunity a decade ago. That puts the government in a tough position. For the U.S. attorney to sew this one up, some other thread and needle must stitch the three timelines together, and I don’t see how that additional element is anything but Kathy Nealy. She’s got to say – or the government has got to prove – that there were specific quid pro quo deals.

Pay Kathy, get John’s vote. Don’t pay the money, don’t get the vote. Something or someone will have to put that together. Otherwise, it’s all just “The Song of the South” set in Dallas, Texas. Everybody can sing “Zip-a-dee-doo-dah” and dance on home.