Mike Brooks

Audio By Carbonatix

Praising God with college students in the auditorium of Christ For The Nations evangelical school in Dallas wasn’t where the mafia might expect to find a former associate turned informant.

But that’s where Robert Borelli was in August 2002, raising his hands in praise with about 500 others at the school, unabashed but still hidden and afraid. Not a tall man or Godfather-sized, he hadn’t started his YouTube channel yet or appeared on the 700 Club. “I didn’t have a lot of stuff out there,” he says. “I felt pretty secure there.”

A high school dropout, Borelli, who was 47 then, worked as a collector and seller for mobsters Anthony “Fat Andy” Ruggiano and Nick “Nicky” Corozzo from the 1970s until the late ’90s. He dabbled in drug trafficking and robbery and “visited” people who didn’t pay their loans. He’d even beaten a couple of murder charges.

Fat Andy’s son, Anthony Ruggiano Jr, calls Borelli a “mob star.”

“He wasn’t wild, but he was violent and dangerous,” says the younger Ruggiano, whose late father was a caporegime for the Gambino crime family. Ruggiano, who was also once in the federal witness program, recently appeared in Netflix’s Get Gotti documentary to discuss the mafia from the old neighborhood in Queens.

“We did bad things,” Ruggiano continues. “We shot people. We stabbed people. We hurt people.”

Borelli entered the Federal Witness Security Program, or WITSEC, in the late ’90s as part of a federal racketeering case in Florida that involved eight other Gambino crime family associates and members, including Fat Andy’s son, whom Borelli was planning to testify against. That’s what led Borelli to Dallas in the early 2000s.

“Texas is like a different world from where I came from,” Borelli says.

Christ For The Nations was like a different universe.

Founded by Gordon Lindsay, a former Assembly of God preacher, and his wife, Freda Lindsay, in 1948, Christ For The Nations has more than 50 affiliated Bible schools in 30 countries. The one in Dallas is in a renovated nightclub on Kiest Boulevard. The Institute is a family-run business, a three-year nondenominational Bible school with more than 40,000 graduates from 75 nations.

Borelli wasn’t like the other graduates.

“Normally, we would say no to [someone like] that,” says Golan Lindsay, the CEO and president of Christ For The Nations and grandson of the school’s founder. “But my grandmother stepped in and gave him the chance.”

Borelli had gone from secret mafia meetings in dimly lit restaurants in New York and Florida to an auditorium in Dallas filled with first-year students perfecting their evangelical ministry. “I’m a very adaptable type of guy,” he says. “My mannerisms was different. My vocabulary wasn’t great, and like I said, my mind wasn’t transformed at the time. It took a lot of work. Some people would say, ‘Hey, you look like one of the guys from the mafia.’ I wasn’t allowed to let the students know about my past or the Witness Protection Program. I had to keep that quiet. It made it difficult, and there were things that I couldn’t do because of my background.”

He could pray and worship with them in the main auditorium. He had a lot to pray for since he’d been kicked out of witness protection the previous year in 2001.

The mafia also knew its former associate, born Robert Engel, was in Texas.

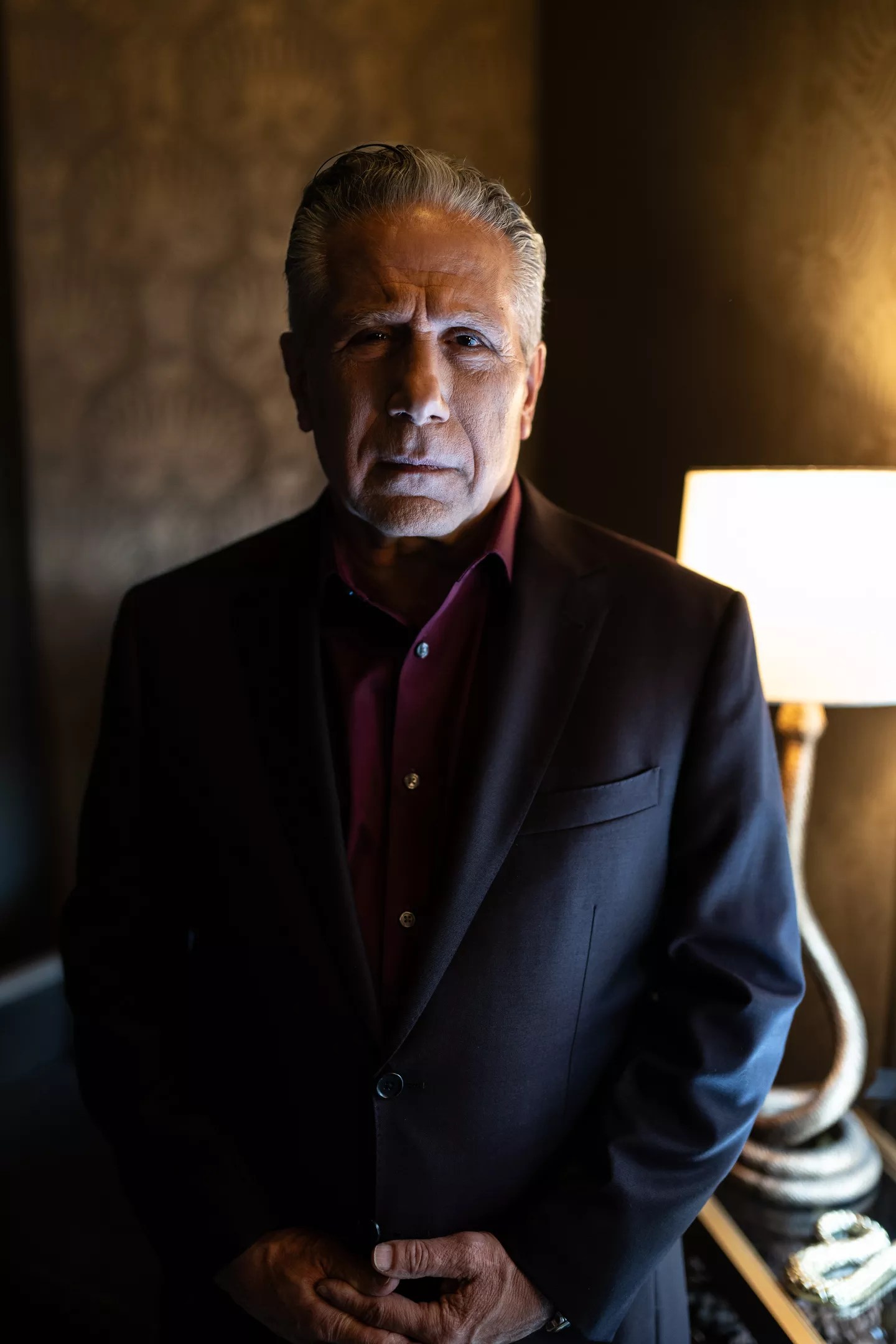

Robert Borelli

Mike Brooks

The Mob Star

Engel met Fat Andy’s son at Tony’s pizza parlor on 93rd Street and 101st Avenue. On a Friday night in the early 1970s, the Queens neighborhood of Ozone Park was where teens lingered on the street corners or across the street in the schoolyard. Engel, then 17, quit school a few years earlier, spent time with street gangs and recently landed a job at an air freight company. He was taking the bus home from work when he bumped into Fat Andy’s godson Little Joe, who invited him to hang out at the pizza parlor.

Anthony Ruggiano Jr. wasn’t much older than Engel. He left school at 16 and began learning the family business. His father was a triggerman for the Gambino family and one of the main wise guys in the area. He’d been the youngest person in the mafia to get “straightened out” – admitted as a full-fledged “made” member in the early 1950s, when Ruggiano says the “books were closed” for membership. The “straightened out” usually involved murder.

Fat Andy, who was 25 then, committed multiple murders for mafia boss Albert Anastasia, a cofounder of Murder Inc., a Brooklyn gang that acted as an enforcement arm of the mafia.

“My father was a gangster, a killer,” Ruggiano says. “He lost his father when he [Andy] was six. His two best friends were connected to the mafia through family. … He was a great father. He used to kiss me on the lips. We had a great relationship. But he hated people who cooperated.”

Extending over 10 blocks in Brooklyn, Engel’s neighborhood included Brownsville and Ocean Hill, areas once known as recruitment grounds for Murder Inc. From the late 1920s until the early 1940s, the Brooklyn gang was responsible for between 400 and 1,000 contract killings, authorities say. Muder Inc.’s reign of killing ended in 1941. Its founder, Louis “Lepke” Buchalter, along with other leaders, died in the electric chair, and assassins gunned down Anastasia in a barber shop in 1957.

But their families remained behind in the neighborhoods.

In the early 1970s, five families made up the New York mafia: the Bonanno, Colombo, Gambino, Genovese and Lucchese. Carlo Gambino, the namesake of his family, was the most powerful boss of the five families. “A couple of families were in the same neighborhood,” Engel/Borelli says. “It’s kind of like how the government’s doing things. You just had boundaries.”

Gambino boss John Gotti came from Engel’s neighborhood. His younger brother Gene Gotti, a high-ranking Gambino mafioso, hung out with one of Engel’s sisters. Nick “Nicky” Corozzo, another high-ranking Gambino mafioso, had his first headquarters in a small candy store in Ocean Hill. When Engel was younger, he worked for Corozzo’s brother Blaise, first selling fireworks, later taking bets on horse races, baseball and other sporting events. He thumped a few heads to get debts paid.

“They got all the money, all the respect, all the attention. They had nice clothes and got pretty girls,” Engel says. “Hanging out with them gave me a place to belong.”

Engel felt that sense of belonging at the pizza parlor in Queens with Ruggiano, who had taken a liking to Engel, whose tough-guy reputation among the local street gangs had been spreading.

It eventually spread to the FBI.

“We knew of him,” says Philip Scala, a retired FBI agent who spent 35 years in the Organized Crime Unit, the last 10 of them as supervisor of the Gambino crime family squad. “I’ve spoken to two or three cooperates and associates like Robert, and these were tough kids involved with murders and beatings. These were people that everybody who knew them would walk on the other side to avoid them. They all tell me … Robert was the real deal.”

Ruggiano knew Engel was the real deal in 1972. He recalls that they began hanging out every day, going to the clubs in Manhattan, doing cocaine and “making money doing mob stuff.”

That mob stuff included …

Well, the first rule of the mob Engel learned: “Never admit to anything.”

“It’s hard for me to explain it,” Engel says. “I don’t want to sound unconscionable. Some of my acts… that was work. Live through the streets, die through the streets, that’s what happens. My concern was not getting caught.”

“Never take a plea” was another rule, followed by “Don’t rat on nobody, keep your mouth shut and do your time like a man,” and whatever you do, “Don’t mess with somebody’s wife. That’s automatic death,” Engel recalls.

“Don’t mess with drugs” was a rule Engel says nearly all of them ignored. The old bosses, among them Paul Casellano, who took over the family in 1976, enforced the rule because drug trafficking led to lengthy prison sentences and possible cooperation with prosecutors in exchange for shorter ones.

Engel was 20 in 1975 when he was arrested for a 1973 murder that involved “a guy who started some trouble,” he says. The man had become aggressive with a knife over drugs that Engel says his companions didn’t have. He died from stab wounds. Fat Andy hid Engel and Little Joe for about a year and then put Engel under the protection of Gambino captain Nick “Nicky” Corozzo, only for Engel to pick up another murder charge in 1974 while hiding out from his first one after a gunshot victim was found dead in a club Engel had visited.

Corozzo became a father figure to Engel. “Nicky taught me a lot about the mob,” Engel says. “After a while, I wanted to be Nicky.”

In 1977, Engel was acquitted of the shooting death. Authorities dismissed the charge in the stabbing death because, Ruggiano says, there were no witnesses.

“It’s sort of like Goodfellas,” says Ruggiano, whose father was portrayed by Louis Eppolito in the movie. “We could go anywhere we want. Robert was well-liked by the mob guys, and I started introducing him to people. ‘Robert, the Mob Star.’ It was just an exciting time.”

Get Clean or Die

Cocaine started as an exciting time for Engel in the 1970s.

Jay Black of Jay and the Americans, a popular rock act in the 1960s, turned Ruggiano on to the drug. Black, who died in 2021, was friends with Fat Andy, Engel says, and took Ruggiano, then 17, to Puerto Rico, where the white powder flowed.

“That was the first time he’d seen cocaine,” Engel recalls.

Ruggiano introduced Engel and Little Joe to it when Ruggiano’s father was hiding them in upstate New York from the first murder charge.

“Joseph didn’t want to do it at first. ‘Nah, I don’t want that shit,'” recalls Ruggiano, who got clean in 1988. “When I got clean and had to do my step work, when I was doing my eighth or ninth step, I went to his grave and made amends.”

Engel began using and selling cocaine for the Gambino crime family. In the early ’80s, he served about two years in prison on a federal case for possession of $200,000 in stolen treasury checks and on two state cases for robbery and possession of a weapon. Engel returned to prison for a year in 1985 for violating his parole on a weapons charge in Manhattan. He’d been robbing furs from a storefront.

By the late ’80s, a friend who freebased with him introduced him to crack. “For a while it was sociable,” Engel says. “After [a] while, I couldn’t maintain business.”

Paranoia accompanied his addiction. He shot his friend in the head because Engel says he thought his friend was stealing drugs from him. The man survived and even managed to run out of the house, only to get hit by the ambulance.

Engel didn’t face charges. “He didn’t tell anybody that it was me.”

In the early ’90s, crack had become Engel’s life. If he had money, Engel says he’d go to a motel, find a girl and get high. He’d stay up for weeks at a time and only fall asleep when he blacked out. Then he’d wake up, do it all again until he was homeless, seeking shelter at crack houses.

He’d often hang out near Fat Andy’s son’s after-hours club in Ozone Park to get high. He’d walk into the club, hustle people for cocaine or a couple of dollars. The guy who ran the joint got hold of Ruggiano, who came to the club to reason with Engel.

But Engel wouldn’t listen to Ruggiano or any other mob friend except for Corozzo, who sent word in ’94 that Engel needed to leave New York. He was becoming an embarrassment to the mafia. “Get clean” was the message.

What would happen if he failed to do so was clear.

Anthony Ruggiano Jr.

Mike Brooks

Busted Again

Engel approached the stolen cargo truck in a quiet industrial area near Fort Lauderdale to count the cigarette cartons in the back. He’d been dealing with stolen cargo since the ’70s when he hijacked cargo trucks from the JFK International Airport in Queens. He already had a buyer for the cigarettes in suburban Deerfield Beach, about 18 miles north of Fort Lauderdale.

A year had passed since he left New York for Miami. Engel had moved in with his mother, gotten clean and found a job cleaning large office buildings downtown. He even got to spend time with his daughter, who was a year old and came to visit him from New York with her mother in July 1994.

Then Ruggiano called in late ’94 and said Corozzo, now the acting Gambino boss, wanted to see him at the Fontainebleau, a luxury hotel in Miami Beach where they were staying. Corozzo had set up loan shark operations at an E-Z Check Cashing in Deerfield Beach. He was offering “shylock loans” at a 260% annual interest rate, cheaper than current legal payday loans that offer 400% yearly rates but don’t threaten beatings for those who fall behind. According to a May 25, 2005, court document, Corozzo’s crew was also participating in extortion, fraud, money laundering and stolen goods such as the stolen cargo truck filled with cigarette cartons.

“It was just a visit,” Engel says. “Nicky wanted to feel me out. It was a couple of times. They were coming back and forth and mentioned to me that this guy needed someone to collect money out of a check-cashing place.”

They gave Engel a list of people who hadn’t paid. He began visiting them. “Actually, I told them nice, ‘You need to pay it. We’re willing to work with you. Start making payments and make a commitment. I’ll come by every week and pick it up,'” he recalls. “Some people were reluctant, and I let them know in a nice way that I could be their friend or their enemy.”

In the summer of ’95, Engel was under the impression that Ruggiano’s brother-in-law, Louis Maione, had gotten the truckload of cigarettes from a contact on a Native American reservation. Other stolen goods were available if Engel was interested. Engel didn’t question Maione’s story. “I’m good with stolen goods,” Engel says. “I can sell ice to an Eskimo.”

He didn’t know that Maione had gotten pinched with 2 kilos of cocaine in Tampa Bay and agreed to wear a wire for the feds. The FBI wanted Anthony “Tony Pep” Trentacosta, who was also doing business in Florida, but then learned that Corozzo was operating in the area and persuaded Maione to wear a wire.

The stolen cigarettes were from the FBI.

A federal grand jury indicted Corozzo, Ruggiano, Engel and five others on 20 counts in December 1996. “Central to the government’s case were wire-tapped phone calls that detailed Gambino dealings with stolen merchandise and Corozzo’s instructions to kidnap and kill an FBI snitch,” the Tampa Bay Times reported in August 1997.

Corrozzo wanted to kill Maione, who wouldn’t be the only one to flip.

Reaching Out to the FBI

Engel heard his daughter’s voice for the first time in early 1997 on a prison phone at Rikers Island in the Bronx. He was facing up to 20 years for a state drug charge in New York and the federal racketeering charges in Florida. He didn’t get rounded up with the others. He had left Florida a few months before the indictment and returned to New York, where he disappeared into the crack houses. He was picked up for selling crack to an undercover officer. Federal agents discovered him in the state judicial system.

The last time he saw his daughter in ’94, Engel spent the day with her and her mother on the beach for the Fourth of July. They watched fireworks and saw a possible future that Engel would ignore when Ruggiano called for Corozzo. Trapped in a jail cell, Engel couldn’t hide from his decision to get high rather than spend time with his daughter.

She was only 4, crying on the phone and wondering why he couldn’t see her.

“All the weight of the guilt and shame shattered my heart,” Engel recalls. “I slammed the phone down and ran back. I didn’t want anyone to see me crying. I cried out to God, ‘Kill me or change me. Please help me.’ God answered the cry, but it wasn’t a miraculous change.”

Engel had been in and out of prison since 1973, but this time, no attorney from the mafia was waiting for him. “I was hoping that they would have one,” he says. “I might have changed my mind. … I felt like they didn’t care about me. I realized it was up to me and that Jesus loved me. That’s how my life started changing.”

Engel called his mother from Rikers and learned that an FBI agent had been hassling her for information about the cigarette case.

You still got his card?

Goodbye, Engel. Hello, Borelli.

Alone in a hotel room in San Antonio, Engel struggled with his decision to enter WITSEC. He thought he’d be able to build a life with his daughter but couldn’t bring her with him into the program since he wasn’t married to her mother and had abandoned her.

Robert Engel was reborn as Robert Borelli. It wouldn’t be his last rebirth.

U.S. marshals paid for Borelli’s motel room in advance for a month, giving him a $40 per diem but expecting him to find a job. He received a new Social Security number but had no work history before 1999, so people were leery about hiring him.

The grocery chain HEB didn’t seem to mind and hired him as a night stocker, Borelli says. He only lasted a couple of weeks.

Borelli’s mother died from lung cancer in early April 1999 while he was transitioning to witness protection after his 24-month prison sentence for the racketeering case. He found out three days after her funeral. His last memory of his mother is looking at her through a plexiglass window in ’97 at the Indian River County Jail in Florida, where he was held as a federal witness. “She never agreed with what I was doing. ‘These guys did so much for you. Why would you do that?'” he recalls her saying.

“I explained it to her, and she said, ‘You just need to do what’s best for you.'”

Back home in the neighborhood, his family distanced themselves from him. “In the neighborhood, I’m considered a rat and a stool pigeon,” he says.

He says his daughter’s mother worried for their daughter’s safety and cut off all contact with him.

Borelli didn’t have to testify against his old crew. Corozzo, Ruggiano and the others took plea deals in August ’97 for one count of racketeering. They received fewer than seven years in prison.

Rebuilding his life didn’t take long. He met someone at a pizza parlor in San Antonio. He’d been sitting alone, and a local Realtor’s family invited him to their table. He followed them to church, where the Realtor, Danny Thompson, served as the pastor. He soon found himself attending Thompson’s church and visiting two nursing homes weekly to share his testimony of overcoming addiction.

At the real estate office, Thompson employed Borelli as a buyer’s agent, which required him to read a script to sell someone a home. The marshals helped him with an apartment and a real estate license. “Soon, I hear him on the phone, ‘What makes you think you can buy a house?'” recalls Thompson, doing his best Michael Corleone impression.

Like the mafia, witness protection had rules. One was, “Never discuss the program.” Borelli violated this rule in the early 2000s when he revealed the truth to Thompson.

“Nobody was upset, and never afraid,” says Thompson, who wondered why Borelli couldn’t return to New York. “He is a sweet guy. He is humble and kind of beaten down because he couldn’t talk to his daughter. It was fairly obvious something was going on. I didn’t bring it up. I figured he would.”

Borelli then broke WITSEC’s “danger zone” rule, which for him meant no contact with the old neighborhood. He married someone from there in the early 2000s. A friend back home introduced them. They spoke on the phone for several months. She flew to San Antonio and never left the area.

Then, Borelli’s sister called to share a discussion with another sister who Borelli says “might have been dating one of the brothers of the guy that I had to testify against.” She wondered what he was doing because everybody from the old neighborhood knew where he lived. It also didn’t help that his face was out there as a real estate agent.

Borelli called to inform the marshals in 2001. “The government threw me out of the Witness Protection Program,” he says.

Taking Flight

Borelli fled with his wife to Utah, where they stayed with a friend for a few months.

Shortly before he fled, Borelli decided to testify against Anthony “Tony Pep” Trentacosta for the government despite being thrown out of the WITSEC program. Trentacosta had taken over as capo after Fat Andy’s death from heart failure in March 1999. His reign only lasted a year. He faced federal racketeering charges for running a crew that committed bank fraud and extortion and strangled a 22-year-old stripper at a motel in Sunny Isles Beach, Florida.

Borelli’s testimony placed Trentacosta at a 1995 meeting in Florida with Corozzo, who was acting as Fat Andy’s stand-in, to recruit someone from Fat Andy’s crew. Fat Andy was in prison on a racketeering charge but still called the shots. They met at a restaurant, where the decision was made not to allow the recruitment.

“It was tough,” says Borelli of testifying against Trentacosta. “I was saved and believed I was doing the right thing, according to God.”

Hiding out in Utah was also tough. He prayed and consulted with his friend. Borelli felt called to the ministry and applied to Christ For The Nations. In 2002, he and his wife moved to the Morning Star dormitory in Dallas. He found a valet job downtown, and she worked as a receptionist.

“I truly believe I was running from myself and believe God was trying to get my attention for the longest time,” Borelli says.

After graduating in 2004, Borelli received a scholarship to attend Criswell College, a private Christian school in Dallas, but he only lasted a year.

“The government kept pulling me out of classes,” Borelli says. “I couldn’t do all the classes, so I had to drop out of some of the classes. And then my English teacher couldn’t deal with me. If I raised my hand, she was like, ‘Oh no.’ She hated my language. She hated the way I talked. Yeah, so she gave me a hard time.”

Borelli and Ruggiano Jr. are reformed mobsterswho now chat about their experiences in podcasts or on YouTube.

Mike Brooks

Going Public

Borelli believed he was doing the right thing, sitting across from Pat Robertson, the 84-year-old face of The 700 Club, to share his story and promote The Witness: A Tale of the Life and Death of a Mafia Madman, a 2014 self-published novel based on his life. (Borelli had appeared on The 700 Club in 2011.)

“There are a lot of criminal organizations,” Robertson told the audience. “We call them the mob. The one that was most familiar was the Italian-Sicilian mob, later called the mafia. There are others besides that. Most of our exposure to these mob influences comes from movies like Goodfellas or TV shows like The Sopranos, but Robert Engel actually lived the life of a so-called wise guy, and he survived to tell about it.”

“I was not a wise guy,” Borelli clarified. “I was an associate. A wise guy would be somebody who was straightened out. A made man, someone who is an official member of organized crime.”

Borelli seemed nervous as he broke the first rule of the mafia, though he kept secret what needed to remain secret. “One of the things I was always told was ‘Never ask questions. If we tell you to do something, you just do it. You don’t need to know why you’re doing it.'”

He was nervous a few years earlier when he met with his daughter. It was their first time together since Florida in the early ’90s. She was nearly a high school graduate. He was now collecting money for Jesus instead of the mob. A Christ For The Nations graduate, he became an associate pastor at Fellowship of Joy in Mansfield from 2003 to 2006 and continued his nursing home ministry until 2015. He started a nonprofit – Back to Acts Ministry – in 2007 and raised money for a church in Kenya that he had visited on a trip with other ministers. He also helped a former Christ For The Nations teacher set up crusades around Texas, Oklahoma and Louisiana

But he was a stranger to his daughter, a teenager in 2010 when they met at a hotel restaurant in Brooklyn. The FBI arranged the meeting for him. They were there with them, waiting and watching from the shadows in case the mafia arrived.

“It was one of the toughest things, and I was hoping to get different results than what I ended up getting,” Borelli says. “Sometimes you watch the movies, and they finally meet their dad. … It was nothing like that.”

Reunited

At The Gaston House in Dallas, Borelli and Ruggiano, now in their 70s, reminisce about their life growing up together in the mafia. A month has passed since their late January 2025 trip to the Mob Museum in Las Vegas, and they’re chatting about old times for Borelli’s YouTube channel, Robert Borelli, which he started in June 2024 to discuss Jesus and the mob.

In a dark suit with a maroon shirt, Borelli offers mobster vibes instead of Texas minister ones inside the historic home, built in the early 1900s. Ruggiano sits across from him at a large dining table that recalls a scene from The Godfather. He’s taller than Borelli, slightly larger around the waist and wears his black hair slicked back like the mobsters in the movies.

Ruggiano talks about his gangster life on his own Reformed Gangsters podcast. He isn’t the only former mafia member with a podcast. Sammy “The Bull” Gravano, a former Gambino underboss, has one. He murdered 19 people and, according to Scala, only did two or three years in prison after he testified against Gotti.

“Now he’s got a podcast and tells 10% of the truth and 90% fabrication,” says Scala, who recommends Mikey Scars: No Excuses with RJ Roger, hosted by Michael “Mikey Scars” DiLeonardo, because he often fact checks Gravano.

This time last year, Borelli appeared on Ruggiano’s podcast to share his mafia madman turned Texas minister story. Ruggiano’s mother saw Borelli on The 700 Club with Pat Robertson in 2014. A phone call later, Ruggiano and Borelli reconnected.

“I was a little cautious going to New York and meeting with him,” Borelli says. “But we knew each other since I was 17 and he was 18. We met up, and it felt comfortable.”

Ruggiano was also in WITSEC. He’d been arrested in 2006 for racketeering and a cold case murder. While others had alibis, Ruggiano was the last to see his brother-in-law Frank Boccia alive in 1988. He took him to Fat Andy’s social club, where Boccia was shot five times for assaulting Ruggiano’s mother.

“We decided that we’re not going to kill him until after the baby is born so my sister won’t have a miscarriage,” says Ruggiano, who left witness protection in 2009 on what he claims were good terms. “That is how sick we are. … So we wait until the christening, and we’re going to kill this guy next week. We’re taking pictures with him and laughing.

“None of this fazes me,” he adds. “…We went out to dinner with guys who we knew were going to die. We knew, like Thursday, they were going to get killed.”

Similar to Borelli, Ruggiano needed an attorney but didn’t receive help from the mafia, despite Gotti sanctioning the killing. The feds offered to help and, with Ruggiano’s testimony, brought down capos Bartolomeo “Bobby Glasses” Vernace and Dominick “Skinny Dom” Pizzonia and family hit man Charles Carneglia.

Ruggiano left WITSEC in 2009 on what he claims were good terms. But he didn’t leave behind the new identity they’d given him – one he doesn’t advertise like Borelli.

“When I started to cooperate, I felt guilty because I loved [my father] and knew how he felt,” Ruggiano tells Borelli.

In late 2014, Ruggiano faced sentencing for Boccia’s murder. Ruggiano’s niece had grown up believing her father had abandoned her like Borelli had done to his daughter. “The anger you left with me is indescribable,” she told him. “… I can’t tell you what that did to me as a child. I pray today that justice prevails.”

Ruggiano’s cooperation led to a time-served sentence for killing his brother-in-law. According to a November 14, 2014, New York Post report, he only spent three days in jail.

“The Robert today is not the Robert over 50 years ago,” says Ruggiano, who now works as a drug counselor. “The Robert you know today, he is a miracle.”

Scala makes a similar claim about Borelli. Scala says he usually rejects interview requests but agreed to speak with the Observer because he believes Borelli is different from the other reformed mobsters. Borelli doesn’t have a disdain for the mob and talks kindly about people like Corozzo and prays for them.

“He is a big believer,” Scala says. “He doesn’t make a lot of money, and I try to help him.”

Scala says the mafia, now mostly Sicilian, changes its business model every time a prosecution takes place. These days, they’re more involved in the legitimate side of business but keep “whatever dark business” close to their inner circle.

“The Bureau doesn’t have any type of cooperation like it did 10, 15 years ago,” Scala says. “People are scared to death of Sicilians in Italy. If people cooperate, they will kill their wife, their kids, everybody.”

Corozzo is now a free man. He just turned 85.

Borelli, though, isn’t worried about retaliation. “I just look at it this way,” he says. “I’m in a win-win situation. I know where I’m going when I die. God saved me for a plan and purpose and for his will to be done in life.”